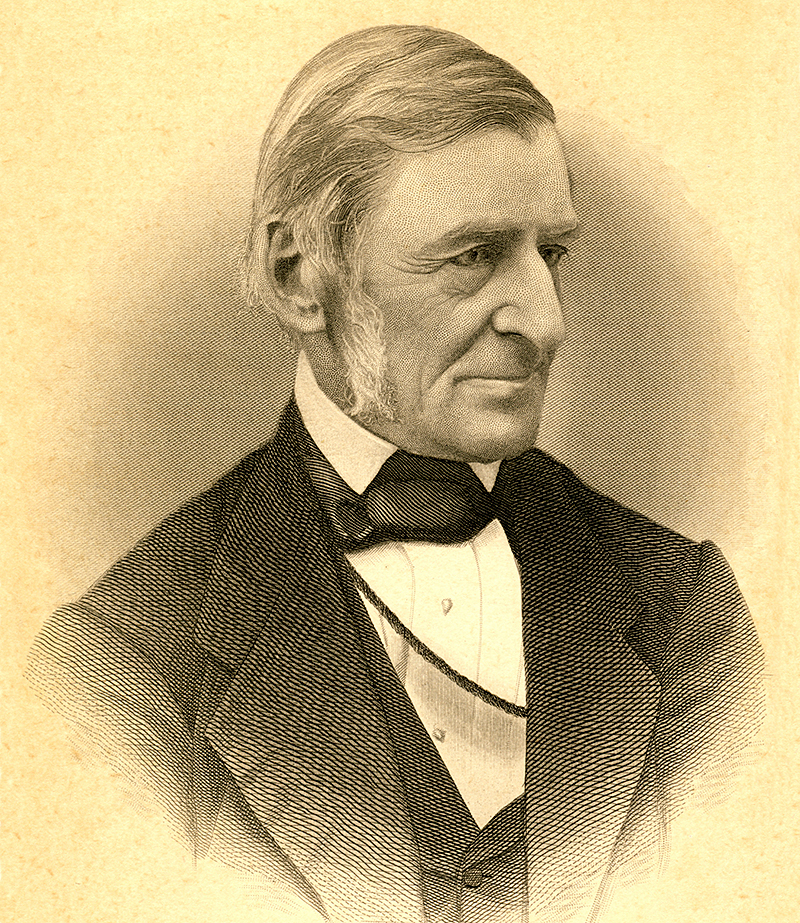

Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1803-1882), ranks as a leading figure in the thought and literature of American civilization. He was an essayist, critic, poet, orator, and popular philosopher. He brought together elements from the past and shaped them into literature that had an important effect on later American writing. He influenced the work of Henry David Thoreau, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Henry James, and Robert Frost.

Emerson’s essays are a series of loosely related impressions, maxims, proverbs, and parables. He has been described as belonging to the tradition of “wisdom literature.” That tradition includes Confucius, Marcus Aurelius, Michel de Montaigne, and Francis Bacon, among others.

Despite personal hardships, Emerson developed a moral philosophy based on optimism and individualism. In “Self-Reliance,” he wrote, “Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind,” and, “Whoso would be a man, must be a nonconformist.”

His life.

Emerson was born on May 25, 1803, in Boston. His early life was marked by poverty, frustration, and sickness. His father, a Unitarian minister, died in 1811, leaving Emerson’s mother to raise five sons. One of his younger brothers spent most of his life in mental institutions. Another brother, also a victim of mental illness, died in 1834. A third brother died in 1836 of tuberculosis.

Until Emerson was 30, he also suffered from poor health, including a lung disease and periods of temporary blindness. In addition, his first wife, Ellen, died in 1831. His first son, Waldo, died in 1842. Emerson wrote one of his finest poems, “Threnody,” for his son.

In 1817, Emerson entered Harvard College, where he developed lifelong interests in literature and philosophy. After graduating in 1821, he taught school briefly. He then returned to study theology at the Harvard Divinity School. In 1826, he was licensed to preach. In 1829, he was ordained Unitarian pastor of the Second Church of Boston. For personal and religious reasons, Emerson grew dissatisfied with this profession. He resigned his pulpit in 1832. After one year’s travel in Europe, Emerson began a career as a writer and lecturer. He died on April 27, 1882.

His prose works.

The sources of Emerson’s thought have been found in many intellectual movements. They include Platonism, Neoplatonism, Puritanism, Renaissance poetry, mysticism, idealism, skepticism, and Romanticism. His prose style was active, simple, and economical.

His first book, Nature (1836), was received with some enthusiasm, particularly by the young people of his day. The book expressed the main principles of a new philosophical movement called transcendentalism. Soon after its publication, a discussion group was formed with Emerson as its leader. It eventually came to be called the “Transcendental Club.” The club published an influential magazine, The Dial, devoted to literature and philosophy. Emerson edited the periodical from 1842 to 1844. See Transcendentalism.

During the 1830’s, Emerson gained a solid, though controversial, reputation as a public lecturer. He also became known as a young man with remarkably forceful and original ideas. In 1837, he gave a famous address at Harvard called “The American Scholar,” in which he outlined his philosophy of humanism. He said that independent scholars must interpret and lead their culture by means of nature, books, and action. He urged his listeners to learn directly from life. He told them that they should know the past through books and express themselves through action. In this address, Emerson proclaimed America’s intellectual independence from Europe. In the so-called “Divinity School Address” (1838), Emerson attacked “historical Christianity.” He favored a new religion founded in nature and fulfilled by direct, mystical intuition of God. He opposed formal Christianity’s emphasis on ritual.

Emerson’s next two books, Essays (1841 and 1844), contain much of his most enduring prose. In “Compensation,” “Spiritual Laws,” and “The Over-Soul,” he stated his faith in the moral orderliness of the universe and the divine force governing it. In “Experience,” perhaps his best essay, Emerson allowed room for skepticism. He showed how doubts are conquered through faith. In “Art” and “The Poet,” he outlined his philosophy of aesthetics. In “Politics” and “New England Reformers,” he explained his social philosophy.

Emerson’s later prose works are more specialized and better organized. Representative Men (1850) is a series of semibiographical, semicritical essays. The subjects are Plato, Emanuel Swedenborg, Montaigne, William Shakespeare, Napoleon, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. They are linked by Emerson’s thesis that “great men” teach us to “correct the delirium of the animal spirits, make us considerate and engage us to new aims and powers.” In English Traits (1856), Emerson recorded his two voyages to Europe and discussed English literature, character, customs, and traditions.

His poetry.

Though in theory Emerson believed that “it is not metres, but a metre-making argument that makes a poem,” he wrote his verse in traditional forms. His poetry is characterized by conventional rhythms, rhyme patterns, and stanza forms. His poems also feature economy of phrasing and simplicity of imagery.

The two volumes of poetry that appeared during his lifetime were Poems (1846) and May-Day (1867). They contain some of the finest American verse of the 1800’s. Emerson developed his mystical religion in “Each and All,” “Hamatreya,” and “Brahma.” He celebrated nature in “The Rhodora,” “The Humble-Bee,” “The Snow-Storm,” and the two parts of “Woodnotes.” See Snow-Storm, The. The poems “Uriel,” “The Problem,” and “The Sphinx” are among Emerson’s most personal expressions. They reflect his frustrations, doubts, and longings. Like these, “Days” reveals a comic portrait, perhaps unintentional, of himself and of his failure to fulfill his “morning wishes.” “Days” is often considered Emerson’s greatest poem.