Encyclopedia is a collection of information about people, places, events, and things. It may deal with all areas of knowledge or it may confine itself to only one area. A general encyclopedia, such as The World Book Encyclopedia, includes information on topics in every field of knowledge. Specialized encyclopedias provide more detailed and technical information on specific areas of knowledge, such as art, medicine, or the social sciences.

In ancient times, scholars found that the information they needed was scattered in manuscripts (handwritten works) in various parts of the world. Some scholars made their own reference works by copying long quotations from the works of other authors. Others copied items of information from a variety of sources. These ancient collections of information were the ancestors of the encyclopedia. But they differ from encyclopedias in many ways. Early scholars presented information in any order they chose, and they had few ways to check its accuracy. In addition, they wrote only for themselves or other scholars. Encyclopedia editors, on the other hand, carefully organize their material and demand accuracy. They also present information to a large, diverse audience.

The word encyclopedia comes from the Greek words enkyklios paideia, meaning general education or well-rounded education. The word did not come into common use in English until the 1700’s. The word encyclopedia sometimes is used in the name of an alphabetically arranged reference work about many parts of a single subject or field. The word cyclopedia, though infrequently used now, also describes a book or set of books giving information on all branches of one subject.

An encyclopedia is concerned with the who, what, when, where, how, and why of things. For example, an article on radar tells what radar is and who developed it, as well as when and where. It also describes how radar operates and why it is important in everyday life.

No one person today can create a full-featured general encyclopedia. Such an enterprise calls for the combined talents of scholars and specialists, of editors and educators, of researchers and librarians, and of artists, mapmakers, book production and manufacturing specialists, information technologists, and specialists in digital publishing. It also calls for a large investment of money by the publisher. To keep an encyclopedia up to date on events in all fields of knowledge, the publisher must revise it on a regular basis.

Until the mid-1980’s, most general encyclopedias were available only in book form. Since then, many encyclopedias have been issued in an electronic format, in which information is presented on the screen of a computerized device. For information on electronic encyclopedias, see the History section of this article.

Preparing an encyclopedia in book form

Much work goes into the preparation of a new encyclopedia or the revision of an already existing one. The publisher must have a clear-cut idea of the encyclopedia’s aims and objectives. That is, the publisher must answer several basic questions. For example, which subjects should be included, and what emphasis should they receive? Who is going to use the encyclopedia? How can the material be arranged to best serve the needs of the audience? What kinds of illustrations, and how many, should be included? What can be done to help readers locate information easily?

Aims and objectives.

Before the editors decide on which subjects to include, they must know the general purpose that the encyclopedia will serve. The development of the subject matter also depends on whether the encyclopedia covers one or many areas of information and study.

The audience

is a central factor in planning an encyclopedia. Some encyclopedias are planned primarily for children. Others are designed for scholars and specialists. Still others are family encyclopedias. Family encyclopedias aim to meet the reference and study needs of students in elementary school, middle school, high school, and beyond. They are also designed as everyday reference tools for the entire family, for teachers, for librarians, and for other people seeking information.

The function of the encyclopedia editor is to provide the reader with information, accurately and objectively, so that it can be readily understood and applied. Editors bridge the gap between what there is to know and the reader who wants to know. They serve as interpreters and translators who present information so that the reader can easily understand it.

Scope of the encyclopedia.

The number of pages and the number of volumes in an encyclopedia depend on the content to be covered, who will use it, and the price for which it will be sold. Regardless of the number of volumes and pages, no encyclopedia has ever contained all the information available on every subject. Many encyclopedias include lists of books to read and websites and other sources to consult for additional information.

Arrangement of content.

Most encyclopedias use one of two basic methods of subject arrangement. These are the alphabetical arrangement and the topical arrangement.

The entries in most encyclopedias, whether the encyclopedias consist of one volume or more than one, are arranged alphabetically. The encyclopedias may have a single alphabetical arrangement from A through Z. Or they may also have a second alphabetical listing—that is, an index. The index may be in a single volume, or it may be divided into segments at the ends of the other volumes. An index directs the reader to information contained in the encyclopedia’s entries and contributes to the usefulness of the encyclopedia.

An encyclopedia arranged on a topical basis presents its content along areas of interest. For example, one volume may be devoted to plants, another to animals, and another to history, the arts, or some other subject.

How does the publisher decide what should be put in each volume? Some encyclopedias have books that are all the same thickness. Others have volumes that vary in thickness. If all the volumes have the same thickness, articles that start with some letters of the alphabet are almost certain to be split among two or more volumes. In this case, each volume must be marked in some way to show which part of the alphabet it contains—usually by showing the titles of the first and last articles in it. The first volume may be marked A to Bib, the second Biboa to Coleman, and so on. Such an arrangement is called the split-letter system.

Encyclopedias that use the unit-letter system have subjects beginning with the same letter of the alphabet in the same volume. In some cases, two or more consecutive letters of the alphabet may be combined into a single volume. A single volume may not be large enough to hold all the articles that start with the same letter, such as C, M, P, or S. In such cases, articles starting with the same letter may be split between two volumes.

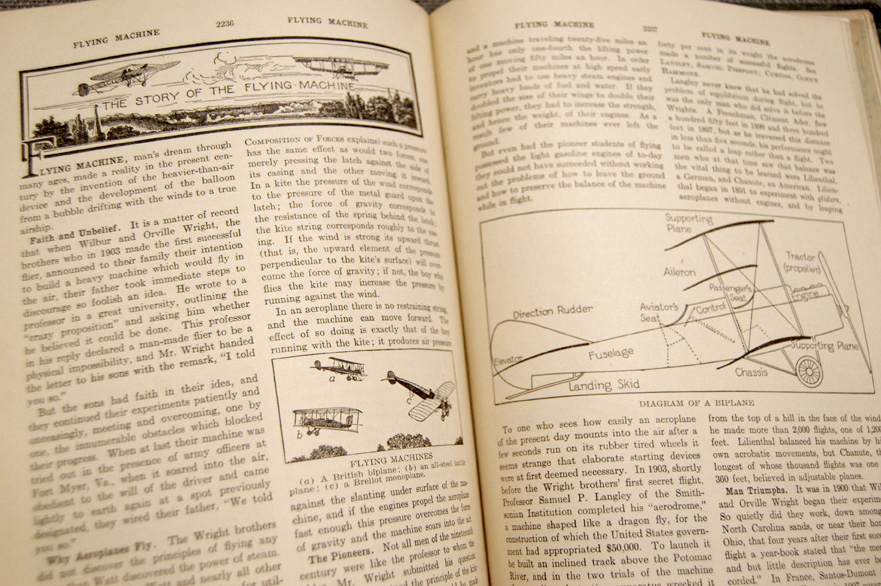

Illustrations

are invaluable to the process of informing and learning. In an encyclopedia in book form, important visual aids include pictures and diagrams. Their educational and informative value depends on the creative flair and ingenuity of editors and artists working together. The illustrations should complement and supplement the information that is given in the text. Illustrations also should be appropriate for the age range of the encyclopedia’s audience. The content of the illustrations must be accurate and visually appealing.

Maps are also an essential feature of a good encyclopedia. Accurate, easy-to-use maps supplement the text. They present important information that can be provided in no other way. Like other illustrations, maps should lie as close as possible to the related text.

Ease of use

is important to every person who wants to look up information in an encyclopedia. Young readers with little experience in using reference works may prefer a single alphabetical arrangement. But they quickly learn the value of an index in finding items of information. The editors must exercise great care in selecting article titles. For example, John Chapman and Johnny Appleseed are the same person. Instead of including two separate articles on him, the editors must choose one place for the article and put an entry cross-reference at the other.

Most encyclopedias use two other kinds of cross-references. One kind occurs within an article. It tells the reader that the subject just mentioned is covered under some other title in the encyclopedia. The other kind appears at the end of an article. It tells readers that the encyclopedia has articles related to the one consulted.

Indexing provides access to detailed information and draws together subjects that have significant relationships. But indexes and cross-references do the reader little good if the articles are not well organized. Ideally, the editors should give the reader ample directions to the organization of each article by using clear headings and subheadings. These headings should together form a logical outline of the subject.

Format,

the physical appearance of each page, can make the encyclopedia look inviting and interesting or cluttered and dull. Artists and designers must decide upon the size of the page, the style and size of the type, the length of each line, the amount of space between lines of type, and the number of columns.

How a

Encyclopedia articles vary in length according to the importance and extent of the subject. Some articles may be only a few lines or a few paragraphs long. Others, such as the World Book article on Painting, may cover more than 60 pages in print. Methods used in preparing these short and long articles differ, depending on the kind and length of the article and on the policy of the publisher.

After an encyclopedia has been published, constant revision is necessary. From printing to printing, the editors must add new articles and revise existing ones to keep the encyclopedia up to date.

Most of the steps described here also apply to the preparation of articles published in electronic forms. Online publication of an encyclopedia allows the publisher to update it continually.

In preparing new or completely revised articles for World Book, the editors follow a careful step-by-step procedure. This procedure ensures that the material meets the aims and objectives of the encyclopedia. The editorial staff decides on the revisions to be made in each print edition and in continual updates of online versions. Vital information on the changing reference needs of the audience comes from recommendations by contributors and consultants. The editors also review information from research into common curriculums and data about the use of World Book. Each new major article passes through the following steps.

Preparing specifications.

World Book editors prepare specifications (a detailed outline) for each article. The “specs,” as World Book editors call them, tell the contributor what the article should include and, in general, how it should be developed.

Before preparing specifications, an editor studies the subject thoroughly to learn what information the article must contain to help a reader understand the subject. The editor also determines the grade or grades at which the material is likely to be used. All this information helps determine not only the content of the article, but also its vocabulary and sentence structure.

Selecting a contributor

is vital to the World Book editorial process. The editors select contributors who are experts in their field. For long, complex articles, such as those on English literature, the sun, or the states of the United States, multiple contributors may be used. Each expert writes about his or her area of specialization. The contributor receives a copy of the specifications and may suggest changes for improvement.

Editing the manuscript

sent in by the contributor calls for expert skill. An editor reads the manuscript to get a general grasp of what has been written. The editor then changes it, as necessary, to conform to World Book policies in matters of content, style, and reading level. A researcher may assist the editor in checking the facts and information. An editor who specializes in handling statistics reviews charts and tables containing such technical data as economic and population statistics. The article editor clarifies any difficult concepts and adds any further facts that may be needed. The manuscript is then checked by copyeditors and sometimes also by educators. The text is stored electronically, where it can be revised easily. After all changes have been made, a copy of the article is returned to the contributor for final approval.

Illustrating the article

calls for the skills of artists, photo and media editors, and layout experts. They work closely with the editor in selecting photographs and in planning artwork for the article. Together, the text and illustrations tell the story. A photo editor obtains photographs and other visual materials to illustrate the article. In some cases, an artist may design diagrams or a cartographer (person who creates maps) may produce maps to include in an article. The layout expert places the illustrations and such features as charts, diagrams, maps, and tables near the text that they are designed to complement and supplement. For the online version of the article, the editor may recommend the addition of other nontext elements, such as audio and video selections, that are available in electronic form.

Providing cross-references

to text and illustrations is another task of editors. The cross-references direct readers to specific facts or articles. Information that might otherwise be missed is thus made easy to find. Editors also check the lists of related articles at the end of new or revised articles.

Indexing

requires the skills of a trained indexer. The indexer selects items to add to the index and puts them into a computer system. The index is finalized after editorial work on the rest of the encyclopedia has been completed.

Preparing for the press.

Editors and designers produce electronic pages, which consist of text and illustrations in digital form. Special electronic files containing this information are then produced and sent to the printing plant. After the plant receives the files, printing plates are made and printing and binding can begin. For more information about the mechanical aspects of making encyclopedias and other books, see Printing and its list of related articles.

How to judge an encyclopedia

If you plan to buy a print encyclopedia or subscribe to or use an online one, you should ask the following questions:

—Is it published by a reputable, experienced, and well-established company?

—Does it have a permanent editorial and art staff?

—Is it authoritative? Are the articles signed by outstanding contributors?

—Is it accurate? Look up articles in fields with which you are familiar. Are the text and pictures understandable? Do they cover all important facts?

—Is it comprehensive? Does it cover subjects in all areas of knowledge?

—Is it up to date? Check articles that deal with current events, such as United States history.

—Is it written without bias?

—Is it written clearly and simply? Can readers of all ages easily understand it?

—Is it well illustrated?

—Is the set easy to use? Check the following items: (a) Does it have a single alphabetical arrangement or some other arrangement? (b) Are the volumes numbered and lettered clearly? (c) Is there a liberal use of cross-references? (d) Is there an accurate and comprehensive index? (e) Is pronunciation given for difficult words? (f) Are the article titles boldly identified?

—Do some articles have lists of related books to read?

—Does the publisher produce a yearbook that reviews the most important events of each year?

—How well are the books made? Is the paper of good quality? Is the printing clear and sharp? Is the binding sturdy?

Before you purchase an encyclopedia, make sure that you understand its basic purpose and plan. If necessary, consult a librarian to make sure that the work is standard and modern. And, after you purchase the encyclopedia, use it! Put it in the place, at home or in school, where it can give maximum service.

History

The first reference works.

Many scholars call the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle the father of encyclopedists. In the 300’s B.C., Aristotle made one of the first attempts to bring all existing knowledge together in a series of books. He also gave his own ideas on many subjects. Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27 B.C.), a Roman writer, made the next attempt. He wrote a nine-volume work on the arts and sciences called Disciplinae (Disciplines). No actual copies of either Aristotle’s or Varro’s works exist today. Scholars know of them only from copies made at a later date. See Aristotle.

Pliny the Elder (A.D. 23-79), another Roman writer, wrote a set of reference books called Historia Naturalis (Natural History). This set is the oldest reference work in existence. It contains thousands of facts, chiefly about minerals, plants, and animals. See Pliny the Elder.

The Chinese compiled their first encyclopedia in the early A.D. 200’s, but no physical trace of it remains. A second encyclopedia, from the late 200’s, was revised in the early 1600’s. The most important early Chinese encyclopedia, compiled by the scholar Du You (also spelled Tu Yu) about 800, emphasizes the things people needed to know to get and hold jobs in the civil service.

Isidore, the Bishop of Seville, completed his Etymologiarum libri XX (Twenty Volumes of Etymologies) in 623. European scholars used this collection of facts as a source book for nearly 1,000 years. But today, scholars seldom depend on it because they cannot check its accuracy. Isidore rarely gave sources for his information.

A scholar in Baghdad, Ibn Qutaiba, compiled the first Arabic reference work. He wrote the Kitab Uyun al-Ahkbar (Book of Choice Histories) in the 800’s. A Persian scholar, al-Khuwarizmi, completed his Mafatih al-Ulum (Key to the Sciences) in the 990’s. He separated what he considered Arab knowledge, including such fields as grammar and poetry, from “foreign” knowledge of such fields as alchemy and logic. The Brethren of Purity, a group of scholars at Basra, a city in what is now the Arab country of Iraq, during the late 900’s produced an encyclopedia that tried to reconcile Greek and Arabic learning.

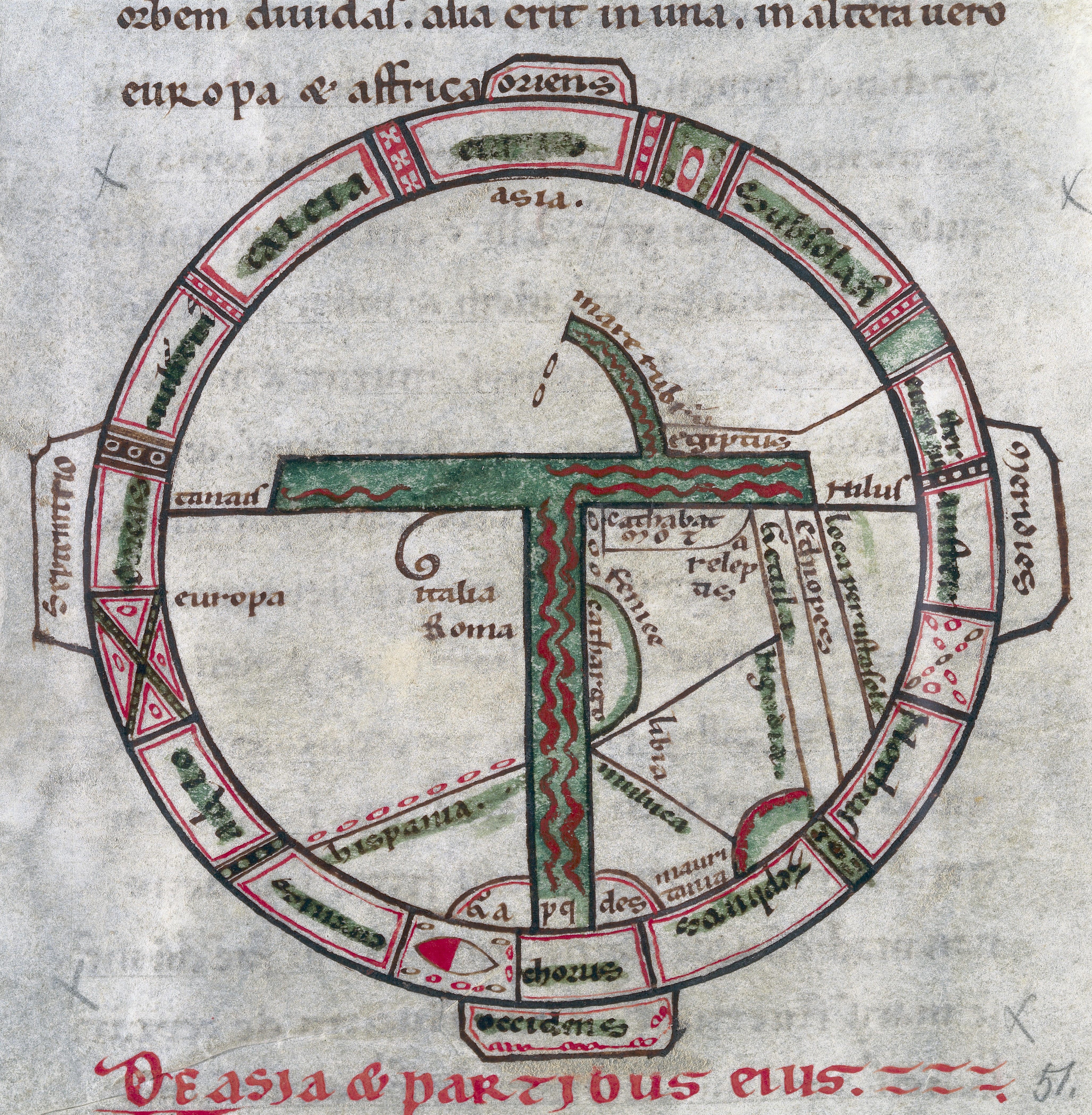

From the 1200’s to the 1600’s,

some original reference works appeared, but most were copies, made slowly by hand. A friar, or member, in a religious order founded by St. Dominic, Vincent of Beauvais, wrote the Speculum maius (Bigger Mirror) in 1244 and revised it many times before he died in 1264. He organized his material under three headings—political history, natural history, and academic subjects. He chose his title because he wanted his work to reflect all human knowledge. Long afterward, scholars continued to use the term speculum (mirror) for a reference work.

Bartholomew de Glanville, a theology teacher in Paris during the 1200’s, wrote De proprietatibus rerum (On the Properties of Things). This work stressed the religious and moral aspects of each topic. Bartholomew wrote in Latin, but his work was soon translated into English, French, and other languages.

In China, the scholar Ma Duanlin completed the huge Wenxian Tongkao (General Study of the Literary Remains) in 348 volumes in 1273. It was published in 1319. Another scholar, Wang Yinglin, completed a slightly smaller work, the Yuhai (Sea of Jade), in 1267. It was published in 1351.

During the late 1400’s, following the European development of movable type for printing, copies and translations of written works became easier to produce than ever before. About 1481, the English printer William Caxton published The Mirror of the World, one of the first reference works in English (see Caxton, William). It was one of many translations of a French work, Mappe Monde (The Image of the World).

Johann Heinrich Alsted, a German Protestant theologian, published one of the last reference works written in Latin. His Encyclopaedia septem tomis distincta (Encyclopedia in Seven Volumes), issued in 1630, stressed geography. Louis Moréri’s Le grand dictionnaire historique (The Great Historical Dictionary), first issued in one volume in 1671, marked a trend of the 1600’s toward publishing such material in local languages.

An age of experiment

in encyclopedias began in 1704 with the publication of the German Reales Staats- und Zeitungs-Lexikon (Dictionary of Government and News). This work was written by a German author, Sinold von Schütz, with a preface written by the scholar Johann Hübner. Schütz later changed its title to include the term Konversations-Lexikon (Dictionary of Conversation). This term has been used in the titles of most German encyclopedias ever since. The work, usually called simply Hübner, established the pattern for many later encyclopedias—all short articles, entirely the work of many contributors, with numerous cross-references.

Also in 1704, an English theologian named John Harris published his Lexicon Technicum. This reference work was the first that presented all articles alphabetically, used articles contributed by specialists, and included bibliographies. Ephraim Chambers, an English mapmaker, published his Cyclopaedia, or the Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, in 1728. He based his work on Harris’s but added elaborate cross-references to simplify the search for information.

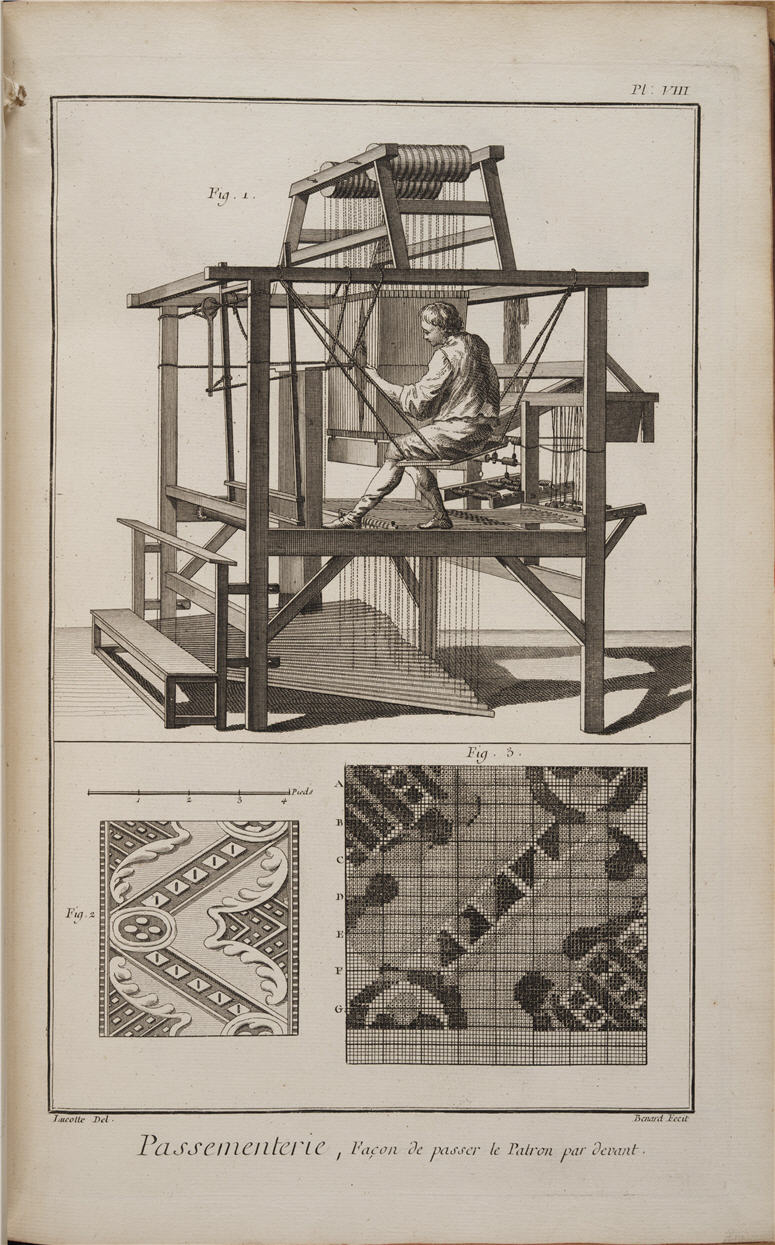

Chambers’s work greatly influenced two French authors, Denis Diderot and Jean d’Alembert. They founded their Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Encyclopedia or Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, the Arts, and the Professions) in 1751. The work was published in 28 volumes between 1751 and 1772. Seven more volumes were added between 1776 and 1780.

Diderot and other French writers of his time were called encyclopedists because of their work. The Encyclopédie contains a number of their revolutionary opinions. Many historians believe it contributed to the movement that led to the French Revolution (1789-1799). See Diderot, Denis.

The Encyclopédie inspired a group of British scholars, who began publishing the Encyclopædia Britannica in 1768. The first edition was completed in 100 installments by 1771. A second edition, which included biographies, appeared between 1778 and 1783. The Britannica established a form that has been followed by many encyclopedias—all extensive articles, some of them more than 100 pages long, on broad topics.

Encyclopedias of the 1800’s and 1900’s.

Pierre Larousse, a former teacher, began to publish Le Grand Dictionnaire Universel du XIX siècle (The Great Universal Dictionary of the 19th Century) in Paris in 1865. His firm brought out Larousse du XX siècle in 1928. La Grande Encyclopédie was published in 31 volumes from 1886 to 1902. It was reissued in the 1970’s. The Grand Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Larousse was published in 1982.

In Germany, Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus, a bookseller, completed his Konversations-Lexikon in 1809. It was published in many editions and translations. The latest edition is called Brockhaus Enzyklopädie. Josef Meyer published a major Konversations-Lexikon in the 1840’s. This work became identified with Nazi propaganda during World War II (1939-1945) and was discontinued. It reappeared in the 1950’s and has been revised several times since then. The Herder Konversations-Lexikon, first published from 1854 to 1857, was later known as Der Neue Herder (The New Herder).

In Canada, the Encyclopedia of Canada was published in six volumes between 1935 and 1938. The 10-volume Encyclopedia Canadiana, which dealt only with subjects of special interest to Canadian readers, appeared in 1958. The first edition of The Canadian Encyclopedia, published as a three-volume set, appeared in 1985. The Junior Encyclopedia of Canada, made for children, appeared in 1990.

In the United States, printers made illegal copies of the Encyclopædia Britannica as early as 1798. The first edition of Encyclopedia Americana appeared in 13 volumes from 1829 to 1833. Francis Lieber, a German American editor, translated much of it from the seventh edition of Brockhaus’s Konversations-Lexikon. A U.S. firm, Sears, Roebuck, and Co., bought Britannica in the 1920’s. In 1943, William Benton, a former U.S. senator and advertising executive, bought a controlling interest in the encyclopedia company. After Benton died, ownership passed to a foundation set up in his name. In 1996, the Swiss investor Jacob Safra bought Britannica from the Benton Foundation. Encyclopædia Britannica ceased publishing its 32–volume print set in 2012, but continues to publish an online edition.

In 1911, Americans published the first one-volume encyclopedia, The Volume Library. It was followed by the Lincoln Library of Essential Information in 1924. The one-volume Columbia Encyclopedia appeared in 1935. The New Columbia Encyclopedia came out in 1975. The one-volume Random House Encyclopedia was published in 1977. The first edition of Academic American Encyclopedia (later also published under the title Grolier Academic Encyclopedia) appeared in 1980. Publication of the nine-volume Oxford Illustrated Encyclopedia was completed in 1993. Other major U.S. encyclopedias of the 1900’s included Grolier’s The Book of Knowledge (1910), the U.S. edition of the British Children’s Encyclopedia; Funk & Wagnalls (1912-1997); Compton’s Pictured Encyclopedia (1922-1968), later published as Compton’s by Britannica; Collier’s Encyclopedia (1949-1998), which replaced other sets first published by the company in 1902 and 1932; the restructured Encyclopædia Britannica (1974, consisting of three sections called the Micropædia, Macropædia, and Propædia; re-released, 1985); and Grolier’s Academic American Encyclopedia (1980), later published as Grolier Academic Encyclopedia.

Electronic encyclopedias first appeared in the mid-1980’s and became especially popular in the 1990’s. One type of electronic encyclopedia, the CD-ROM (C_ompact _D_isc _R_ead-_O_nly _M_emory) _encyclopedia, could store, on a single compact disc, the same amount of information found in a multivolume encyclopedia. Readers accessed information by using a computer with a CD-ROM drive. The first encyclopedia issued on CD-ROM was The Electronic Encyclopedia of 1986, based on The Grolier Academic Encyclopedia. CD-ROM and DVD-ROM encyclopedias called multimedia encyclopedias provided video, sound, and motion in addition to text.

Today’s encyclopedias

may consist entirely of long articles or short articles, or they may contain both. Print encyclopedias may appear in one volume or in many volumes. Most print encyclopedias are alphabetically arranged.

Online encyclopedias became increasingly popular in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, and eventually replaced CD-ROM and DVD-ROM encyclopedias. Online searching involves linking a computer to a network to access information stored on databases at other locations.

Continuing into the 2000’s, most encyclopedias were updated and maintained only in their electronic formats. However, World Book continued to carry out extensive revisions of its print encyclopedia, as well as its online versions. Other leading electronic encyclopedias included variations of Encyclopedia Americana, Encyclopædia Britannica, Compton’s Interactive, and Grolier Multimedia. In 2001, a free online encyclopedia called Wikipedia appeared. Wikipedia is a collection of interlinked web pages called wikis that permit anyone to read, create, or edit articles. Later versions of free, wiki-based content included Scholarpedia, launched in 2006 and focused on academic topics; Citizendium, launched in 2007; and Google’s Knol, launched in 2008 and discontinued in 2012. In 2009, one of the earliest of the electronic encyclopedias, Encarta, was discontinued by Microsoft.

World Book was first published in 1917 in 8 volumes. It grew to 10 volumes in 1918. The editors began a system of continuous revision in 1918 and a yearly revision program in 1933. They began to use analyses of contents of courses of study in 1936 and of classroom use of reference works in 1955. The set grew to 13 volumes in 1929, to 19 in 1933, and to 20 in 1960. The set expanded to 22 volumes in 1971, when an index was added. The index was compiled with the aid of a computer-based information retrieval system.

In 1961, World Book became the first encyclopedia published in braille. In 1964, World Book was published in a large-type edition. In 1980, World Book became the first encyclopedia reproduced as a voice recording. The recorded edition included audio cassette tapes, a special audio cassette player, and indexes reproduced in braille and large type. A Commemorative Edition of the encyclopedia was published in December 2016, marking the 100th anniversary of the publication of the first edition.

In 1990, World Book, Inc., produced the The World Book Information Finder. This CD-ROM product featured the text and 1,700 tables from The World Book Encyclopedia and 225,000 entries from The World Book Dictionary. The World Book New Illustrated Information Finder, which was introduced in 1994, included pictures and maps as well as text.

The World Book Multimedia Encyclopedia, which was introduced in 1995, added animation, videos, and audio. In 1997, World Book and International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) combined their resources to produce a major revision and enhancement of the CD-ROM version of World Book. This electronic reference work contained hours of multimedia technologies, including videos, animations, simulations, virtual realities, audio, pictures, and maps. World Book Online, an online version of World Book, became available to schools and libraries on a subscription basis in 1998 and to individual and home subscribers in 1999. This product, incorporating an atlas, a dictionary, and other features, was renamed World Book Online Reference Center in 2003. In 2008, this publication was redesigned for use by students in upper elementary through intermediate grades and was renamed World Book Student.

In 1999, World Book launched a 13-volume general reference set, The World Book Student Discovery Encyclopedia. Written at a reading level lower than that of World Book, it provided a bridge to World Book for students of all ages, especially young readers. Subsequent editions were titled Discovery Encyclopedia. This publication was followed by a science reference set, The World Book Student Discovery Science Encyclopedia (2005). A topically organized edition of the set was first published in 2013 as the Discovery Science Encyclopedia.

In 2006, World Book Kids, an online product based on the Student Discovery Encyclopedia, was first published. Kids was extensively redesigned and expanded in 2015. World Book Advanced, designed for secondary and postsecondary students, was launched in 2007. In 2008, World Book Discover was added to the group of online publications. Discover was designed to complement differentiated instruction methods. Differentiated instruction is a teaching theory based on the idea that students vary in background knowledge, academic readiness, language, and other ways, and so should have multiple options for taking in information and understanding ideas. Versions of these publications adapted for use on mobile devices, such as tablet computers, began to appear in 2013.

World Book added the interactive Timelines publication to its line of digital publications in 2014. In 2019, to better support beginning readers, World Book released Early Learning. In 2020, World Book added Wizard, a classroom-based, adaptive learning platform, to Student.