Europa << yu ROH puh >> is the fourth largest moon of Jupiter. It has a smooth, icy surface. Beneath the ice is an ocean of liquid water. Such an ocean could provide a home for living things.

Europa’s diameter is 1,940 miles (3,122 kilometers). It is slightly smaller than Earth’s moon. Europa takes 85.2 hours, or about 3.5 Earth days, to orbit Jupiter once. It takes the same amount of time for Europa to rotate once on its axis. As a result, the same side of Europa faces Jupiter at all times. Europa orbits Jupiter at an average distance of 417,000 miles (671,100 kilometers).

Structure and composition.

Europa has a thin atmosphere. The atmosphere is made of oxygen, but it is too thin for people to be able to breathe. Scientists think Europa has an icy crust, a layer of ocean, a thick layer of rock, and a core made of metal.

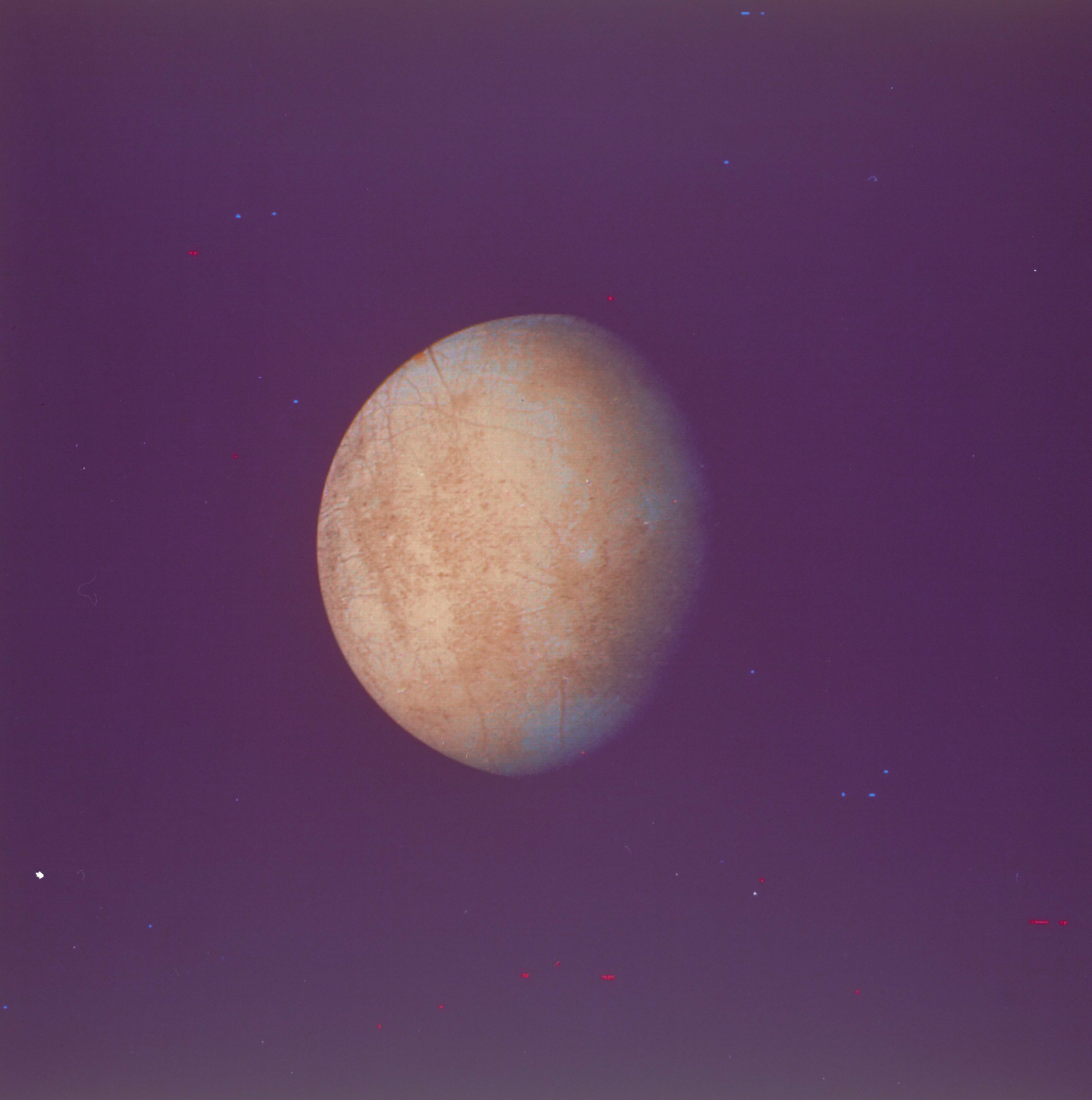

Europa has one of the smoothest surfaces of any body in the solar system. Its surface features include shallow cracks, valleys, ridges, pits, blisters, and icy flows. None of them extend more than a few hundred yards or meters upward or downward. In some places, huge sections of the surface have split apart and separated, then refrozen.

Europa’s crust is made of frozen water. The solid ice is 10 to 15 miles (16 to 24 kilometers) thick, but there may be warmer, slushier ice beneath it. Areas known as chaos terrain seem to be made of ice that has broken up and frozen in place. Some scientists think that chaos terrain is produced when lakes underneath the ice collapse.

The ice crust has dark, reddish-brown streaks and patches. These darker areas are ice contaminated with salty minerals, such as sodium chloride and magnesium sulfate. Some of these minerals have probably risen up from the ocean. Others are produced when intense radiation strikes the surface. Electrically charged particles from Jupiter’s radiation belts continuously bombard Europa. The radiation may cause Europa’s night side to glow in the dark.

Europa’s interior is hotter than its surface. This internal heat comes from the gravitational forces of Jupiter and of Jupiter’s other large satellites, which pull Europa’s interior in different directions. As a result, the interior flexes, producing heat in a process known as tidal heating. The heat prevents Europa’s underground ocean from freezing.

Underneath the ice crust, Europa’s ocean is probably 40 to 100 miles (65 to 160 kilometers) deep. Europa may have twice as much water as Earth. Earth is much bigger than Europa, but its oceans are less than 7 miles (11 kilometers) deep.

Evidence for a subsurface ocean.

Scientists have not directly proved the presence of a subsurface (underground) ocean on Europa. No spacecraft capable of gathering direct proof has approached the moon closely enough. However, astronomers and planetary scientists think the ocean exists, based on observations of Europa’s properties. If the ocean did not exist, it would be difficult to explain these observations. Thus, scientists agree that Europa most likely has a subsurface ocean layer.

Images of Europa’s surface show few large craters. The presence of only a few large craters shows scientists that a moon or planet is geologically active. Impact craters, which are formed when an asteroid or other object strikes the surface, occur occasionally on all moons and planets. If a moon or planet is not geologically active, its surface becomes covered with craters over billions of years. On Europa, however, the splitting and shifting of the surface has destroyed most of the old craters.

The cracks and other formations in Europa’s surface ice give scientists hints about what is taking place beneath the ice. The way the ice shifts suggests that it is floating on a layer of liquid, rather than being frozen directly onto bedrock.

Europa does not produce its own magnetic field. But Jupiter’s magnetic field is disrupted in the space around Europa. The disruptions are most likely caused by something inside Europa that conducts (carries) electricity. Because magnetism is closely related to electricity, a layer of electrically conductive fluid would produce the disruptions. And because Europa has so much water ice, scientists think the conductive fluid inside Europa is salty water.

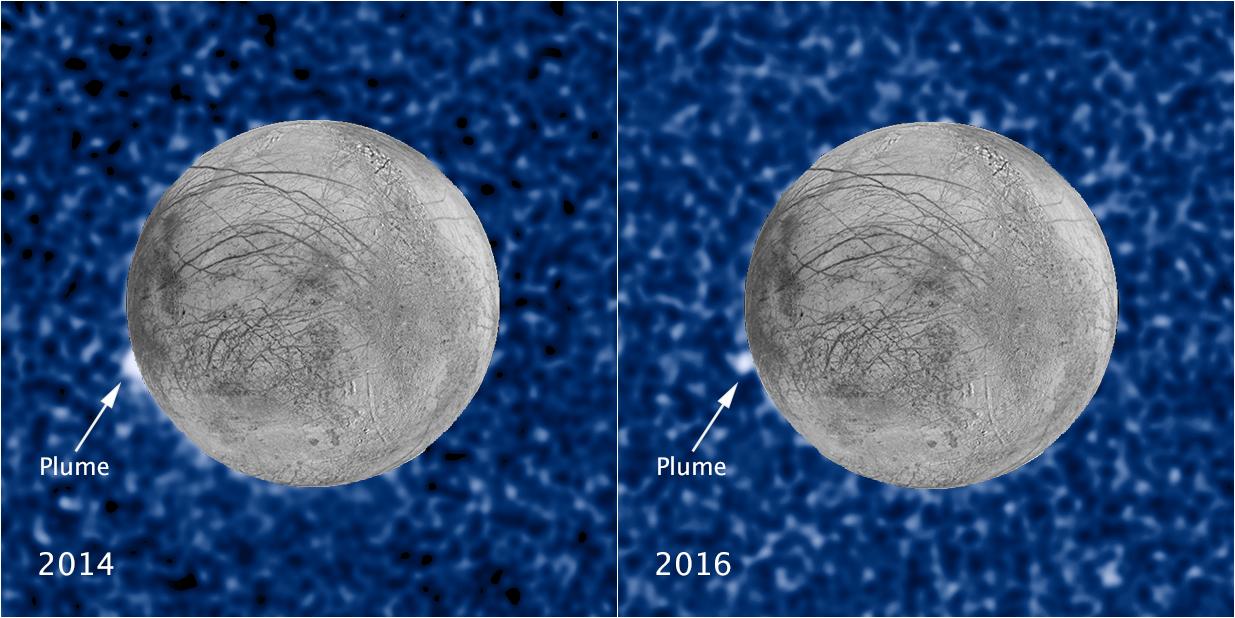

Europa’s ocean probably erupts into space through cracks in the crust. Such eruptions are known to occur on Enceladus, a moon of Saturn.

History of study.

In 1610, the Italian astronomer Galileo discovered Jupiter’s four largest moons: Ganymede, Callisto, Io, and Europa. These are known as Jupiter’s Galilean moons. The Galilean moons can be seen in the night sky by anyone with a pair of binoculars or a small telescope. All four were named after characters in Greek mythology.

In the 1950’s, astronomers used telescopes to discover large amounts of frozen water on Europa. Astronomers continue to study Europa with powerful telescopes, such as the Hubble Space Telescope and the Keck Observatory. The space probe Pioneer 10 photographed Europa in 1973. But few details were visible in the blurry image it produced. The Voyager probes passed by Europa more closely in 1979. Voyager images clearly showed long, dark cracks in Europa’s ice.

Two Jupiter probes, Galileo and Juno, have provided the most detailed studies of Europa so far. Galileo orbited Jupiter in the 1990’s and 2000’s. Juno is still active and is expected to study Jupiter and its moons until at least 2025.

Planetary scientists aim to study Europa in greater detail with two new missions. The European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission launched in 2023. The JUICE spacecraft will visit Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, dedicated entirely to studying Europa, is expected to launch in 2024. JUICE and Europa Clipper will not reach Europa until the early 2030’s.