Flour is the ground powder of grains or other crops that serves as a basic ingredient in many important foods. Flour made from ground wheat is used to bake bread. Wheat flour is also the main ingredient in such foods as cakes, cookies, crackers, pancakes, and pasta. Other grains that are ground into flour include barley, corn, millet, oats, rice, and rye. Still other kinds of flour are produced by grinding beans, nuts, seeds, or such tubers (underground stems) as potatoes and cassava.

Bread ranks as the world’s most widely eaten food, and people in many countries receive much of their nourishment from foods made with flour. Each person in the United States eats an average of about 120 pounds (54 kilograms) of flour from wheat and other grains annually. Canadians eat an average of about 135 pounds (61 kilograms) of flour per person each year.

By the 9000’s B.C., prehistoric people were grinding crude flour from wild grain by crushing the grain between rocks. Later, the ancient Greeks and Romans used water wheels to power flour mills.

The chemistry of flour.

Flour consists mostly of molecules called carbohydrates, an important source of nutrition. The carbohydrates in flour are chiefly starches. When heated, starches absorb water and swell. Cooks thus use the starches in flour to thicken sauces, stews, puddings, and pie fillings.

Wheat flour contains special molecules that, when moistened, form a sticky, stretchy substance called gluten. Along with starches, gluten gives structure to baked goods. In a batter or dough, sheets of gluten hold in expanding bubbles of carbon dioxide gas created by such leavening agents as yeast or baking powder. Gluten thus helps baked products rise, rather than remain flat and dense. However, some people’s digestive systems cannot tolerate gluten. They must avoid foods made with wheat flour.

Types of flour.

In the United States, Canada, and Europe, most of the flour people use is called white flour. It is ground only from the inner parts of wheat kernels. Whole-wheat flour is made by grinding entire wheat kernels. Whole-wheat flour does not form gluten as readily as white flour does. Whole-wheat flour also gives foods a rougher texture and stronger flavor than does white flour alone.

There are three main types of white wheat flour: (1) bread flour, (2) cake flour, and (3) all-purpose flour. The three types of flour differ primarily in their protein content. Bread flour contains at least 11 percent protein. Cake flour contains less than 81/2 percent protein. All-purpose flour generally has a protein content of about 101/2 percent.

The more protein flour has, the stronger the gluten it forms. Bakers use high-protein bread flour to make breads with a sturdy, chewy texture. Cake flour, with its low protein content, results in baked goods with a more tender texture. All-purpose flour is often used in cookies, pie crusts, dinner rolls, biscuits, and other baked goods that require a balance between sturdiness and tenderness.

Other types of flour have different uses in cooking and baking. Flours made from barley and rye form smaller amounts of gluten than does wheat flour. Other flours do not form gluten at all. Buckwheat and rice flour are used to make certain kinds of Asian noodles. Corn meal, made from grinding corn kernels, is an important ingredient in corn bread and tortillas.

How white flour is milled.

Wheat kernels form the raw material for white flour. They consist of a tough covering called the bran, a mellow inner part called the endosperm, and a tiny new wheat plant called the germ. To make white flour, millers separate the endosperm from the bran and germ and then grind the endosperm into flour.

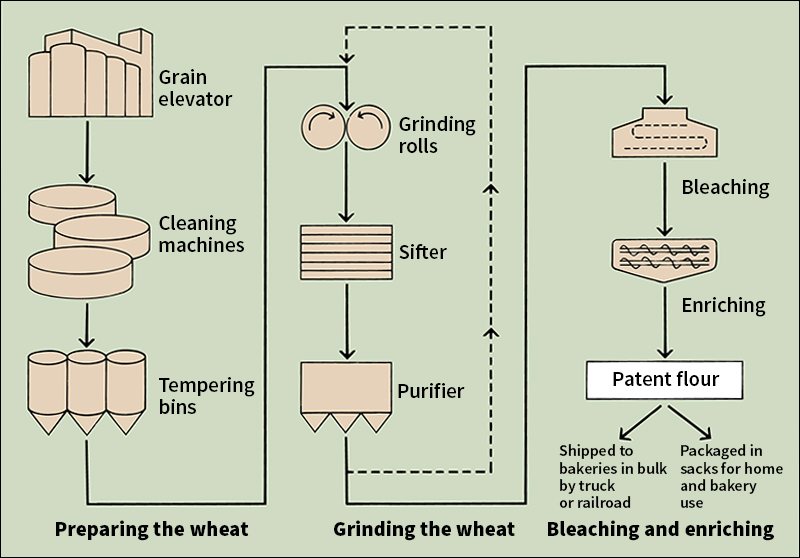

Various cleaning machines first remove dirt, straw, and other impurities from the grain. Next, the wheat is tempered (moistened). The moisture makes the endosperm more mellow and the bran tougher.

The tempered wheat passes between a series of rough steel rollers that crush the endosperm into chunks. Pieces of bran and germ cling to the chunks of endosperm or form separate flakes. Then the crushed grain is sifted. The tiniest bits of endosperm, which have become flour, pass through the sifter into a bin. Larger particles collect in the sifter. Next, these larger particles are put into a machine called a purifier. There, currents of air blow flakes of bran away from the endosperm particles. The endosperm particles are then repeatedly ground between smooth rollers, sifted, and purified until they form flour. In most mills, about 72 percent of the wheat eventually becomes flour. The rest is sold chiefly as livestock feed.

Newly milled white flour is cream-colored, but some mills bleach it to make it white. They may also add chemicals that strengthen the gluten. Some chemicals both bleach the flour and strengthen the gluten. Such treatments must be carefully controlled because the addition of too much of a chemical ruins the flour.

Wheat is rich in starch, protein, B vitamins, and such minerals as iron and phosphorus. However, the vitamins and some of the minerals are chiefly in the bran and germ, which milling removes from white flour. Most millers in the United States and many other countries enrich their product by adding iron and vitamins to white flour made for home use. Before enriched white flour became widely available in the 1940’s, many people who relied on foods baked with white flour suffered from malnutrition.

History.

People probably began to make crude flour between 15,000 B.C. and 9000 B.C. They used rocks to crush wild grain on other rocks. After farming began to develop, people made flour from such cultivated grains as barley, millet, rice, rye, and wheat.

By the 1000’s B.C., millers ground grain between two large, flat millstones. Later, domestic animals or slaves rotated the top stone to crush the grain. The Persians, a people living in what is now Iran, probably developed windmills for grinding grain during the A.D. 600’s. By the 1100’s, windmills were powering flour mills in Europe.

Few further advances in milling occurred until 1780. That year, in England, a Scottish engineer named James Watt built the first steam-powered flour mill. In 1802, Oliver Evans, a Philadelphia miller, opened the first such mill in the United States. During the late 1800’s, metal rollers replaced millstones in many American and European mills. Edmund La Croix and other millers in Minneapolis, Minn., perfected the purifier in the 1870’s. By the early 1900’s, automation had made flour mills more productive than ever.