Fruit commonly refers to the edible tissue that surrounds the seed or seeds of many flowering plants. People around the world enjoy eating fruits as desserts or snacks. In fact, the word fruit comes from a Latin term meaning enjoy. Fruit growers worldwide produce hundreds of millions of tons of fruit annually. The most popular kinds include apples, bananas, grapes, oranges, peaches, pears, plums, and strawberries. Fruits make up an important food group in a healthful human diet. They provide rich sources of vitamins and carbohydrates (starches and sugars).

The term fruit has a somewhat different meaning for botanists (scientists who study plants) and for horticulturists (experts in growing plants). Botanists define fruit as the part of a flowering plant that contains the seeds. By this definition, fruits also can include acorns, cucumbers, and tomatoes.

Horticulturists describe fruit as an edible seed-bearing structure that (1) consists of fleshy tissue and (2) grows on a perennial (a plant that lives for more than two growing seasons). This definition excludes nuts, which do not have a fleshy body, and vegetables, which typically grow on annuals (plants that live for only one growing season). It also excludes many foods that most people consider fruits. For example, watermelons meet both the botanical and common definitions of fruit. But horticulturists regard them as vegetables because they grow on annual vines. Many people also consider rhubarb a fruit because of its use as a dessert. But people eat the rhubarb leafstalk, not the seed-bearing structure. Thus horticulturists and botanists classify rhubarb as a vegetable.

This article describes the different categories of fruits in botany and in horticulture. It then discusses how people cultivate and market fruit and how they develop new fruit varieties called cultivars.

Types of fruits in botany

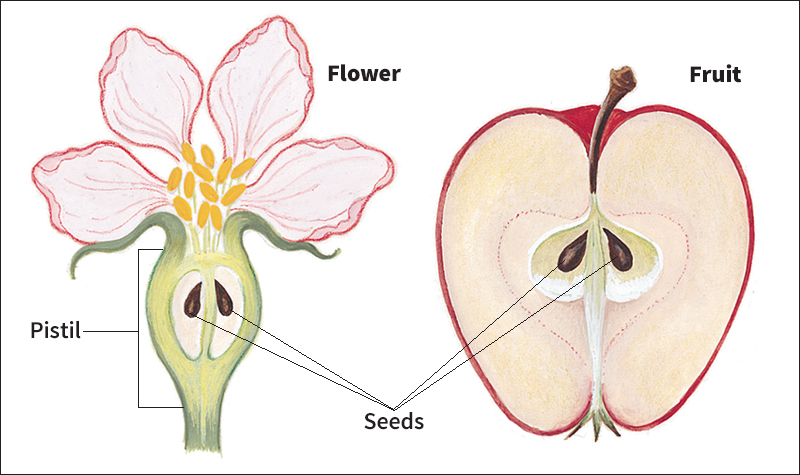

Fruits grow on flowering plants, which scientists call angiosperms. A fruit develops from the plant’s ovary, the tissue surrounding the seed-bearing structure of the flower. Flowers may have one or more ovaries. Each ovary contains one or more seeds, depending on the plant. Fruits protect the seeds and help them to disperse (scatter) to form new plants. Many fruits have three layers after they mature: (1) an outer layer called the exocarp, (2) a middle layer called the mesocarp, and (3) an inner layer called the endocarp. Collectively, the three layers make up the pericarp.

Botanists classify fruits into two main groups, simple fruits and compound fruits. Simple fruits develop from a single ovary. Compound fruits develop from two or more ovaries.

Simple fruits

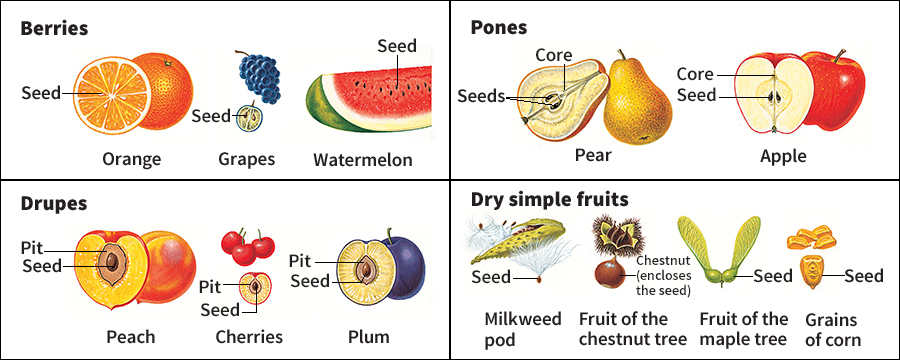

make up by far the largest group of fruits. Many simple fruits have a fleshy pericarp, and others have a dry pericarp. There are three main kinds of fleshy simple fruits: (1) true berries, (2) drupes (pronounced droopz), and (3) pomes (pronounced pohmz).

True berries include bananas, blueberries, green peppers, grapes, oranges, tomatoes, and watermelons. Some of these fruits, known as pepos << PEE pohz >> have a firm exocarp. They include muskmelons and watermelons. Berries called hesperidiums << hehs puh RIHD ee uhmz >> possess a leathery exocarp. Citrus fruits rank as the best known hesperidiums. Many fruits that have the word berry in their common name, such as blackberries, raspberries, and strawberries, are not in fact true berries. Scientists classify them as compound fruits.

Drupes possess a fleshy mesocarp surrounding a hard endocarp called a stone or pit. A thin exocarp forms the skin. Examples of drupes include apricots, cherries, olives, peaches, and plums.

Pomes have a distinctive core. The core consists of a thin, paperlike endocarp surrounding hollow, seed-bearing cavities. Apples and pears rank among the most popular types of pomes.

Dry simple fruits include beans, milkweed, peas, rice, wheat grains, and true nuts. Botanists regard true nuts as single-seeded fruits with a hard pericarp called a shell. People eat the seeds of these plants but not the pericarps. True nuts include acorns, chestnuts, and hazelnuts. Some so-called nuts, almonds for example, are actually the seeds of drupes. In fact, food-processing companies frequently substitute apricot seeds for almonds in processed foods.

Compound fruits

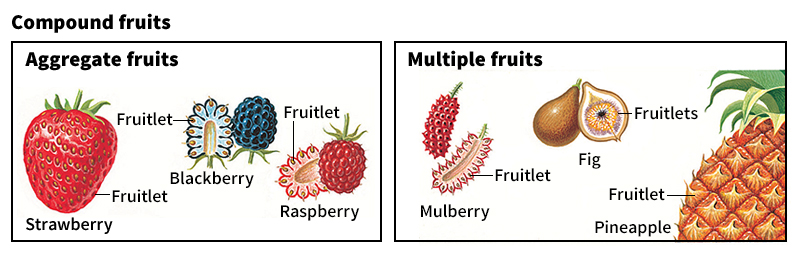

consist of a cluster of ripened ovaries. There are two main types of compound fruits, aggregate fruits and multiple fruits.

Aggregate fruits develop from single flowers, each of which has many ovaries. The strawberry represents an unusual type of aggregate fruit. Each so-called seed on a strawberry is a true fruit. Botanists call these seedlike fruits achenes << ay KEENZ >>. The edible fleshy part surrounding the achenes develops from the base of the flower rather than from the ovaries. Other aggregate fruits include blackberries and raspberries.

Hand picking strawberries

Multiple fruits grow from a cluster of flowers on a single stem. Figs, mulberries, and pineapples are multiple fruits. Botanists also consider an ear of corn to be a multiple fruit. Each kernel forms a single fruit called a caryopsis << kar ee AHP sihs >>.

Types of fruits in horticulture

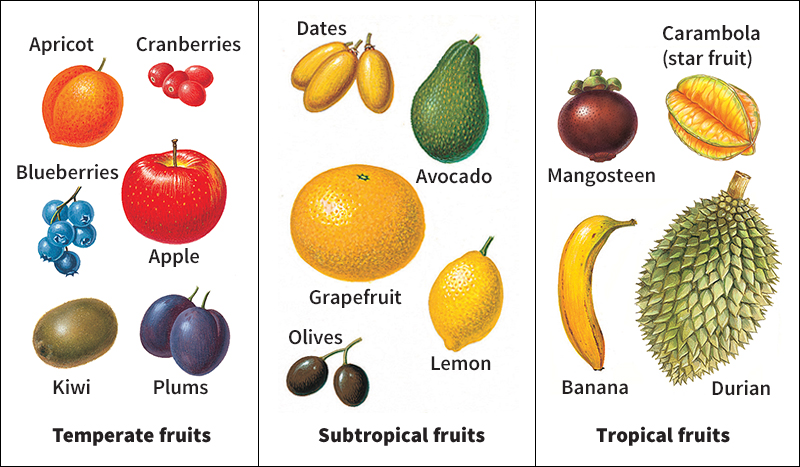

Farmers have long cultivated various fruits far outside the areas where the plants originally grew. Peaches, for example, once grew only in China but now thrive in many parts of the world. Horticulturists classify fruits into three groups, based on their temperature requirements for growth: (1) temperate fruits, (2) subtropical fruits, and (3) tropical fruits.

Temperate fruits

need an annual cold season to grow properly. Farmers raise them chiefly in the temperate regions between the tropics and the polar areas. Most temperate fruits thrive in Europe and North America. They also grow in Asia, Australia, and New Zealand. Such temperate fruits as apples, apricots, cherries, peaches, pears, and plums grow on trees. Temperate areas also produce many fruits that grow on plants smaller than trees, including blueberries, cranberries, grapes, kiwis, raspberries, and strawberries.

Subtropical fruits

require warm or mild temperatures throughout the year but can survive an occasional light frost. This type of climate characterizes subtropical regions. The most widely grown subtropical fruits, the citrus fruits, consist primarily of grapefruits, lemons, limes, and oranges. Brazil, Israel, Italy, Mexico, Spain, Turkey, and the United States all have important citrus-growing regions. Other subtropical fruits include avocados, figs, and olives.

Tropical fruits

cannot tolerate even a light frost. Bananas and pineapples rank as the best-known tropical fruits. Growers cultivate them throughout the tropics, mostly for export. Other tropical fruits include acerolas, cherimoyas, litchis, mangoes, and papayas.

Fruit production

Many fruit species (kinds) grow on trees or other long-lived woody plants. Tree fruits include apples, mangoes, and the major citrus fruits. Grapes develop on woody vines, while many other small fruits grow on bushes. Bananas and strawberries develop on plants that have non-woody stems.

Unlike most other crop plants, fruits do not grow from seeds. Instead, they develop from such plant tissues as stems, buds, and roots in a process called vegetative reproduction. Plants grown from seeds may vary in many ways from generation to generation. But plants grown vegetatively display similar growth habits and yield fruit of similar quality. Fruit growers strive to propagate (reproduce) plants in which such traits remain as consistent as possible over time.

Growers propagate fruit plants in three main ways: (1) by grafting, (2) from cuttings, and (3) from specialized plant structures. Most fruit trees require the grafting method. In this process, the grower joins a bud or piece of stem from a desirable cultivar to a rootstock from another plant. A rootstock is a root or a root plus its stem. The resulting tree will produce the desired fruit. Moreover, the rootstock may influence such tree characteristics as size, productivity, and disease resistance.

Farmers propagate some plants by rooted cuttings or specialized structures, such as modified stems called runners. Rooted cuttings consist of pieces of stem that have grown roots when placed in water or moist soil. Mature strawberry plants send out long, thin runners that grow along the surface of the soil. Where the runners touch the ground, modified buds called nodes form roots that produce plantlets (new leaves and stems). These plantlets are actually part of the parent plant but can develop into new plants if separated from the parent.

Most growers buy fruit plants from nurseries that specialize in propagating them. Nurseries produce plants under controlled conditions to reduce or eliminate diseases and insects. They often sell their plants with a guarantee that the plants are pest-free.

A branch of horticulture called pomology deals with growing fruit. Pomologists have developed efficient methods of planting, tending, and harvesting fruit.

Planting.

Because fruit plants are perennials, growers need not replant them annually. Trees and vines may remain productive for 30 to 50 years or longer. Small fruit plants, including strawberries and raspberries, have a productive life of only a few years. Farmers in mild climates typically plant trees, bushes, and vines in the fall. In cold climates, planting often occurs in spring.

In the past, farmers almost always grew full-sized, free-standing fruit trees. They generally planted the trees from about 20 to 40 feet (6 to 12 meters) apart to allow room for growth. Today, however, most growers prefer specially propagated dwarf trees. Workers space these trees closer together, from about 4 to 20 feet (1.2 to 6 meters) apart. Closer spacing produces a larger crop in the same area. Smaller trees also enable growers to care for and harvest the crop more easily.

Caring for the crop.

Most fruit growers use machinery to fertilize, cultivate, and irrigate the plantings. Farmers must fertilize fruit plants at least once a year. Some fertilizers are applied to the soil, while others are sprayed on the plants. Many growers cultivate the soil around young fruit plants periodically. This practice encourages crop growth by controlling weeds and improving the circulation of air and water through the soil. Most fruit plants require considerable moisture. Only a few fruits, such as dates and olives, can grow in dry regions without irrigation. If irrigation is needed, growers use ditches or sprinklers to distribute the water.

Some fruit plants, including blueberry bushes, are free-standing. But growers must train other types, such as grapevines, raspberry bushes, and many young fruit trees, to grow on trellises or other supports. Some trees may even need their trunks propped up so that the trees develop a uniform shape and sturdy structure. Fruits grown on supports receive maximum sunlight, producing a more uniform and better quality product. Supports also make harvesting easier.

Nearly all fruit plants need pruning at least annually. Growers must prune the plants to rid them of unproductive or diseased branches. Most growers also remove some of the crop from trees during the early stages of fruit growth. This practice, called thinning, helps increase the size and quality of the remaining fruit.

Fruit growers often use a system of integrated pest management (IPM), which combines natural and chemical controls to fight pests. Farmers usually apply chemical pesticides with tractor-pulled sprayers or specially equipped light airplanes or helicopters.

Sudden spring frosts can endanger fruit crops in temperate or subtropical regions. Growers may use water distributed by sprinklers to protect plants from frost damage. Water releases heat as it freezes. If sprinkled onto the crops continuously, the water protects flowers and young fruit from freezing. Another method of frost protection uses large fans on towers. The fans can mix naturally occurring warm air 30 to 50 feet (9 to 15 meters) above the ground with the colder air at plant level.

Harvesting.

Most fruits ripen quickly after reaching their mature size. Harvesting occurs at different stages of the growth process, depending on the type of fruit and its intended use. Some fruit crops require harvesting when still immature. They include the gooseberries and cherries used to make artificial coloring. For apples, bananas, peaches, and pears, commercial harvesting occurs when the fruits reach full size, but before they ripen. Most fruits taste best if left to ripen on the plant, so home gardeners typically harvest their crops when ripe. Citrus fruits do not go through a distinct ripening process. Thus harvesting can take place over a long period after they mature.

Fruits bruise more easily than do most other crops, so growers must harvest them with care. Workers pick most fruit crops by hand. However, the increasing cost of hand labor has encouraged the use of fruit-harvesting machines. Some of these machines have arms that shake the fruit loose from the plants. The loosened fruit drops onto outstretched cloths. Other harvesting machines have a rubber fingerlike structure that gently “combs” fruit from the plants.

Once the fruit has been harvested, farmers usually deliver it immediately to cold storage or controlled atmosphere storage facilities. There the fruit can finish ripening under controlled conditions. When the fruit becomes ready for market, workers wash it, sort it, and pack it into containers. They then ship the fruit to such buyers as retail stores. Some fruits, including apples, can remain fresh for about a year if stored at temperatures near freezing. But most small fruits or tropical fruits remain fresh for only a few days or weeks in storage. Farmers ship much fruit directly from farms to food processing plants. These plants preserve fruit by such methods as canning, drying, and freezing. Processors often use imperfectly formed fruit in jams, preserves, juices, and other products.

Marketing fruit

The worldwide marketing of fruits has expanded dramatically since the late 1900’s. Because of improved transportation and storage techniques, most major food markets now offer fresh fruit grown and shipped from thousands of miles or kilometers away. Such technology enables markets to offer fruits out of season. For example, apples ripen in the fall. But because the Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere experience fall at opposite times of the year, markets in one hemisphere can sell fresh apples out of season by importing them from the other hemisphere. Thus markets in the United States can sell apples in spring that they have imported from New Zealand.

Technology also has made more types of fruits available in many countries. Such fruits as carambolas (also called star fruit), durians, and mangosteens once rarely appeared outside the tropics. Today, however, they have become available in much of the world. Human immigration helps further increase the variety of fruit in a particular country. Many immigrants bring unusual fruits with them from their old countries to their new homes. Therefore, nations with large immigrant populations often have especially rich and varied fruit markets.

Developing new fruit cultivars

Horticulturists have modified numerous original fruit species to create improved cultivars. Scientists use several methods to develop new cultivars. In one traditional method, they crossbreed two or more existing cultivars that have different desirable characteristics. Such crossbreeding creates a single new cultivar that exhibits desirable traits from both of its parents. Crossbreeding programs best suit small fruit plants that have short life cycles. Plants with longer life cycles make the process too time-consuming.

Another method for developing cultivars involves using sports or chance seedlings with desirable characteristics. Sports are mutations (random changes) that typically occur on individual branches or buds of plants. In chance seedlings, entire young plants exhibit unusual traits. Fruit plants propagated from sports or chance seedlings can inherit their desirable traits. Horticulturists employed this method to create many of the best known fruit cultivars, including Delicious apples and varieties of navel oranges.

Since the late 1900’s, scientists have increasingly used genetic engineering techniques to develop new cultivars. Genetic engineering involves altering a plant’s genes (units of heredity) to give the plant certain desirable traits. Horticulturists often call such techniques transgenic technology.

Transgenic technology enables breeders to focus on precisely the characteristics they want improve in a cultivar. For example, the first genetically modified (GM) food to reach the commercial market was a tomato. Breeders incorporated a gene into this tomato that slowed the ripening process. This genetic modification permitted growers to harvest the fruit at a riper, more flavorful stage. It also enabled the fruit to remain in good condition in the market longer. Other genetic modifications have incorporated vitamins and other nutrients into plants. Still others have improved the plants’ resistance to diseases, weed killers, and drought.

Genes used in transgenic technology may come from organisms other than plants. For example, scientists have inserted a gene from a bacterium into several types of crop plants. This gene enables the plants to produce a bacterial protein that kills certain insects when they feed on the plants.

Despite the potential benefits of transgenic technology, there are also potential problems. For example, some people fear that this new technology may produce unintended consequences that cause harm to the environment. Some also fear that the patenting of GM cultivars may give corporations unreasonable monopolies over the production and marketing of such crops. Mainly for these reasons, various governments are considering bans on the sale of GM foods.