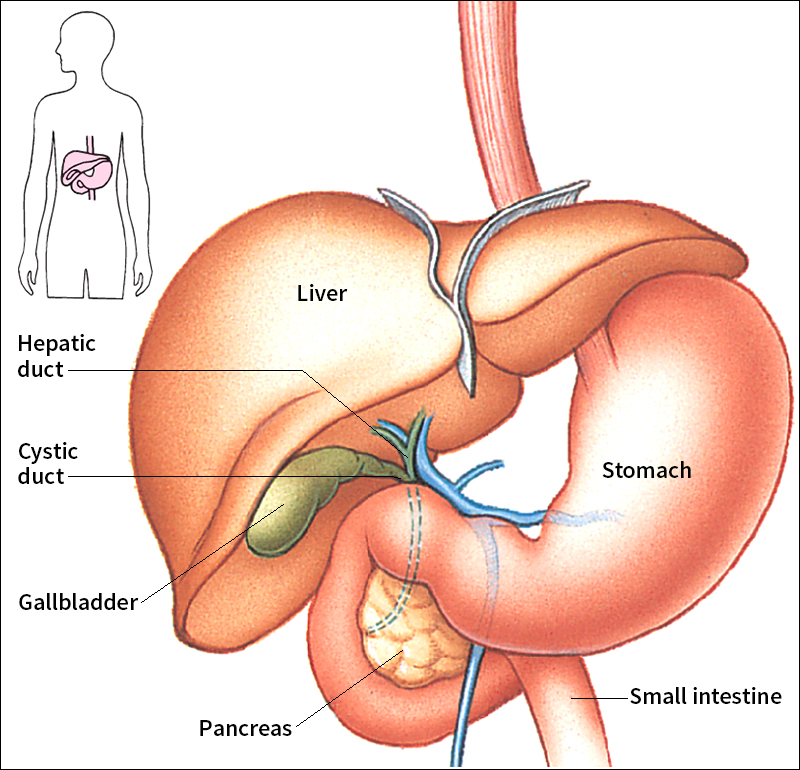

Gallbladder is a small pouch that stores bile. Many, but not all, animals with backbones have gallbladders. In human beings, the gallbladder is a pear-shaped sac that rests on the underside of the right portion of the liver. The gallbladder can hold about 11/2 ounces (44 milliliters) of bile at one time.

The neck of the gallbladder connects with the cystic duct, which enters the hepatic duct, a tube from the liver. Together, these two tubes form the common bile duct.

During digestion, bile flows from the liver through the hepatic duct into the common bile duct and empties into the duodenum, which is the first section of the small intestine. Between meals, the bile is not needed but it continues to flow from the liver into the common bile duct. It is kept out of the duodenum by a small, ringlike muscle called the sphincter of Oddi, which tightens around the opening. The fluid then is forced to flow into the gallbladder, where it is concentrated and stored until it is needed for digestion.

The gallbladder is made to contract by action of a hormone called cholecystokinin << `kol` uh `sihs` tuh KY nihn >> . This hormone is formed in the upper part of the small intestine.

Gallstones sometimes form within the concentrated bile. These small, hard masses may become stuck in the common bile duct, causing severe pain. Blockage of the common bile duct may lead to jaundice, a yellowing of the skin resulting from an accumulation of bile in the blood (see Jaundice ). Doctors commonly treat gallstones by surgically removing the gallbladder. This operation once required a hospital stay of a week or more. Today, the procedure can be done through a laparoscope, and the patient often can leave the hospital the next day (see Laparoscopy ). Some gallstones can be dissolved by taking a medication. Others can be treated by using a device called a lithotripter. The lithotripter produces shock waves that break the stone into tiny fragments.