Garfield, James Abram (1831-1881), was the last president of the United States to be born in a log cabin. Nobody knows what kind of president he would have been because he was assassinated only a few months after taking office. Garfield, a Republican, was the fourth president to die in office. He was the second to be assassinated.

Possibly Garfield accomplished more by his death than if he had lived to complete his term. A major characteristic of national politics in his day was the spoils system. Under the spoils system, thousands of government employees were fired every time a new president took office. Garfield spent most of his short time as president filling these jobs with his political supporters. He was not a reformer, but he recognized the problems with the spoils system. He wrote in his diary, “Some civil service reform will come by necessity after the wearisome years of wasted presidents have paved the way for it.” The assassination of Garfield by a disappointed jobseeker shocked the nation into action. Two years later, Congress began civil service reform with the Pendleton Civil Service Act.

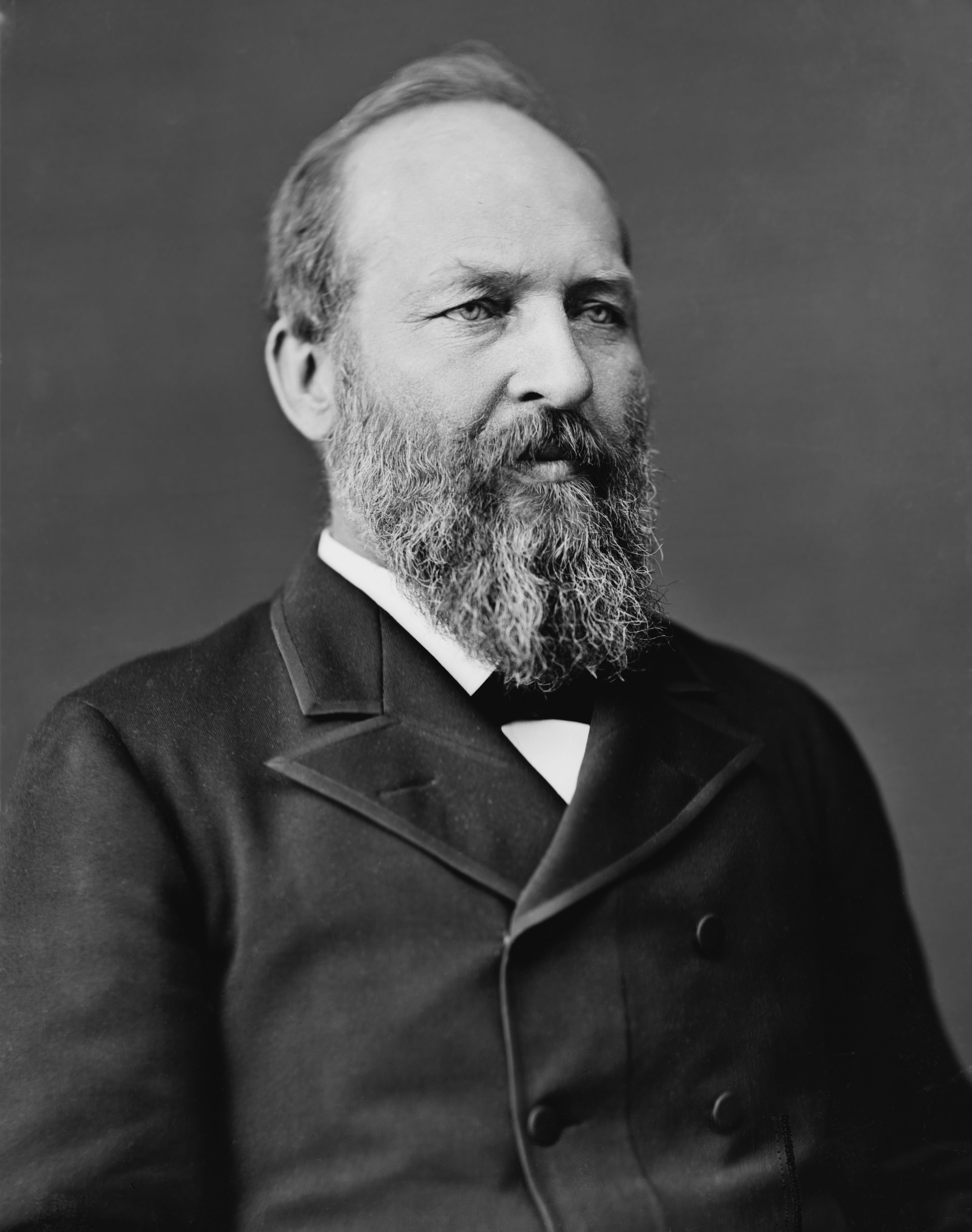

Garfield was a big, athletic, handsome man. He had blond hair and a beard. Before becoming president, he was successful in a number of positions. He had been a professor, college president, Civil War general, and U.S. congressman. He spoke and wrote well, read widely, and even composed poetry. He occasionally entertained his friends by writing Greek with one hand and at the same time writing Latin with the other. Garfield was warmhearted and genial. He wanted to be well liked and generally was. But his eagerness to please everyone sometimes led him into questionable dealings with unscrupulous people.

Early life

Childhood.

James Abram Garfield was born in Orange, Cuyahoga County, Ohio, on Nov. 19, 1831. He was the youngest of five children. His parents, Abram and Eliza Ballou Garfield, were pioneers from the East. His father died before James was 2 years old. Eliza Garfield managed to make a fair living on their 30-acre (12-hectare) farm. She became the first woman to attend a son’s inauguration as president.

In his early teens, James began to do odd jobs during his vacations from the district school. At 16, he left home with the romantic idea of becoming a sailor on the Great Lakes. He had been inspired by reading adventure stories. He gave up the notion when a ship captain cursed him and drove him away. A cousin then hired him to drive a team of horses that towed a barge along the Ohio Canal. During his six weeks on the canal, he recalled, “I fell into the canal just fourteen times and had fourteen almost miraculous escapes from drowning.”

Education and early career.

Soon James returned home, ill with malaria. After he recovered, he entered Geauga Seminary in the nearby town of Chester. Following his first term, he supported himself by teaching in the district school. At 20, he enrolled in the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (now Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio, near Cleveland. He studied and taught some classes there for three years. Then he attended Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, for two years. There he came under the guidance of the president of Williams College, Mark Hopkins. Garfield matured greatly and broadened his interests. He later defined the ideal college as “a simple bench, Mark Hopkins on one end and I on the other …”

After graduation from Williams in 1856, Garfield returned to Hiram College as a professor of ancient languages and literature. The next year, at the age of 26, he was chosen president of the college. While president, Garfield studied law. He occasionally preached sermons for the Disciples of Christ. He had joined that church as a youthful convert.

Garfield’s family.

On Nov. 11, 1858, Garfield married Lucretia Rudolph (April 19, 1832-March 13, 1918). Lucretia was the daughter of an Ohio farmer. She had been a student of Garfield’s at Hiram and taught school while he completed his education. Garfield called her “Crete” and came to rely on her quiet strength. Later, when she was mistress of the White House, he wrote: “Crete grows up to every new emergency with fine tact and faultless taste.”

The Garfields had seven children, two of whom died as infants. One son, Harry Augustus Garfield (1863-1942), became president of Williams College. He also served as fuel administrator under President Woodrow Wilson during World War I (1914-1918). Another son, James Rudolph Garfield (1865-1950), served as secretary of the interior in President Theodore Roosevelt‘s Cabinet.

Soldier.

Shortly after the outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-1865), Governor William Dennison, Jr., commissioned Garfield a lieutenant colonel of Ohio volunteers. The young officer wrote home: “I am cheerful and happy as any one can be in such a fierce business as killing men.” Garfield won a minor battle in Middle Creek, Kentucky, in January 1862. As a reward, he was made a brigadier general. He was the youngest brigadier in the Union Army. He took part in the Battle of Shiloh and in the operations around Corinth. In 1863, as chief of staff under General William S. Rosecrans, Garfield distinguished himself in the Battle of Chickamauga. He rode under heavy fire to deliver an important message to General George H. Thomas. He was promoted to major general after the battle.

Political career

Congressman.

Garfield had shown an interest in politics as early as 1856. That year, he campaigned for John C. Frémont, the Republican candidate for president. Garfield was elected to the Ohio state senate three years later. In 1862, while still in the Army, Garfield was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. However, Garfield did not resign his commission until December 1863.

Garfield won reelection to the House eight times. He served as chairman of the appropriations committee. He also was a member of the committees on military affairs, ways and means, and banking and currency. He supported the harsh Reconstruction measures of the Radical Republicans. He voted for the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson.

In 1872, Garfield was one of several congressmen accused of accepting bribes from Credit Mobilier. Credit Mobilier was a railroad construction company seeking favors from the government. He denied the charge, and it was never proved. Garfield was also criticized for accepting a $5,000 fee from a company trying to get a paving contract from the city of Washington, D.C. He admitted taking the fee but contended that his services were not improper.

Garfield served on the commission that settled the disputed Hayes–Tilden election of 1876. He also helped make the arrangements that gave the presidency to Rutherford B. Hayes.

During Hayes’s administration, Garfield became floor leader of the Republicans in the House. The party was divided into two factions. Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York led one faction, the “Stalwarts.” Senator James G. Blaine of Maine led the other group, the “Half-Breeds.” These groups quarreled over personal differences and government jobs. In general, the Half-Breeds were more interested in modernizing the Republican Party and appealed to younger Republicans. Though closer to the Half-Breeds, Garfield stood between the two factions. He kept some of the confidence of both.

Election of 1880.

The Ohio legislature elected Garfield to the U.S. Senate in 1880. But before he could take his seat there, he led his state’s delegation to the Republican National Convention. The Half-Breeds tried to nominate Blaine for president. The Stalwarts insisted on former President Ulysses S. Grant.

Neither Blaine nor Grant could gather enough votes for the nomination. The Half-Breeds then swung to Garfield. He was a “dark horse,” or little-known candidate. The convention finally chose Garfield on the 36th ballot. For vice president, the convention selected Chester A. Arthur, a Stalwart. Arthur had been Conkling’s lieutenant in the New York Republican machine. Garfield defeated his Democratic Party opponent, Winfield Scott Hancock, by 1,898 votes.

Garfield’s administration (1881)

The five Garfield children, ranging in age from 8 to 17, looked forward to moving into the White House. But the president was in a somber mood. He wrote: “I am bidding good-bye to private life and to a long series of happy years which I fear terminate in 1880.”

Party quarrels

soon confirmed the president’s fears. Garfield, who owed his nomination primarily to the Half-Breeds, favored this faction in handing out jobs. He made their leader, Blaine, his secretary of state. He appointed several others to important offices. The Stalwarts received only minor positions. Their leader, Conkling, tried to stop the Senate from confirming some key appointments. He failed and resigned from the Senate. Distracted by these quarrels, Garfield could give little attention to other government business. He did support an investigation by Postmaster General Thomas L. James. James found fraud in the awarding of contracts to transport the mail.

Assassination.

On July 2, 1881, Garfield was about to leave Washington to attend the 25th reunion of his class at Williams College. He was walking through a reception room in the railroad station when a stranger fired two pistol shots at him. Garfield fell. The assassin cried: “I am a Stalwart and Arthur is president now!”

The assassin, Charles J. Guiteau, was arrested immediately. He held a grudge because Garfield had refused to appoint him as United States consul in Paris. At his trial, Guiteau acted like a madman. His attorney argued that he was innocent by reason of insanity. A jury, however, convicted him. He was hanged in 1882.

Garfield lay near death for 80 days. Although one of the assassin’s bullets had merely grazed his arm, the other had lodged in his back. Surgeons could not find it. Alexander Graham Bell tried unsuccessfully to locate the bullet with an electrical device.

Garfield remained calm and cheerful throughout the hot summer in Washington. He performed only one official act, the signing of an extradition paper. The Constitution provides that, in case of a president’s “inability to discharge the powers and duties” of his office, “the same shall devolve on the vice president.” But a vice president had never done so. Arthur did not step in for fear of disturbing Garfield and creating a major political controversy. The Cabinet supported his decision.

If the X ray and modern antiseptics had existed at that time, Garfield’s life might have been saved. But infection set in. After being moved to a seaside cottage in Elberon, New Jersey, he died on Sept. 19, 1881. He was buried in Cleveland. Friends raised a large fund to help Lucretia Garfield and their children.