Gettysburg Address is a short speech that United States President Abraham Lincoln delivered during the American Civil War at the site of the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. He delivered the address on Nov. 19, 1863, at ceremonies to dedicate a part of the battlefield as a cemetery for those who had lost their lives in the battle. Lincoln wrote the address to help ensure that the battle would be seen as a great Union triumph and to define for the people of the Northern States the purpose in fighting the war. Some historians think his simple and inspired words, which are among the best remembered in American history, reshaped the nation by defining it as one people dedicated to one principle—that of equality.

Loading the player...Abraham Lincoln

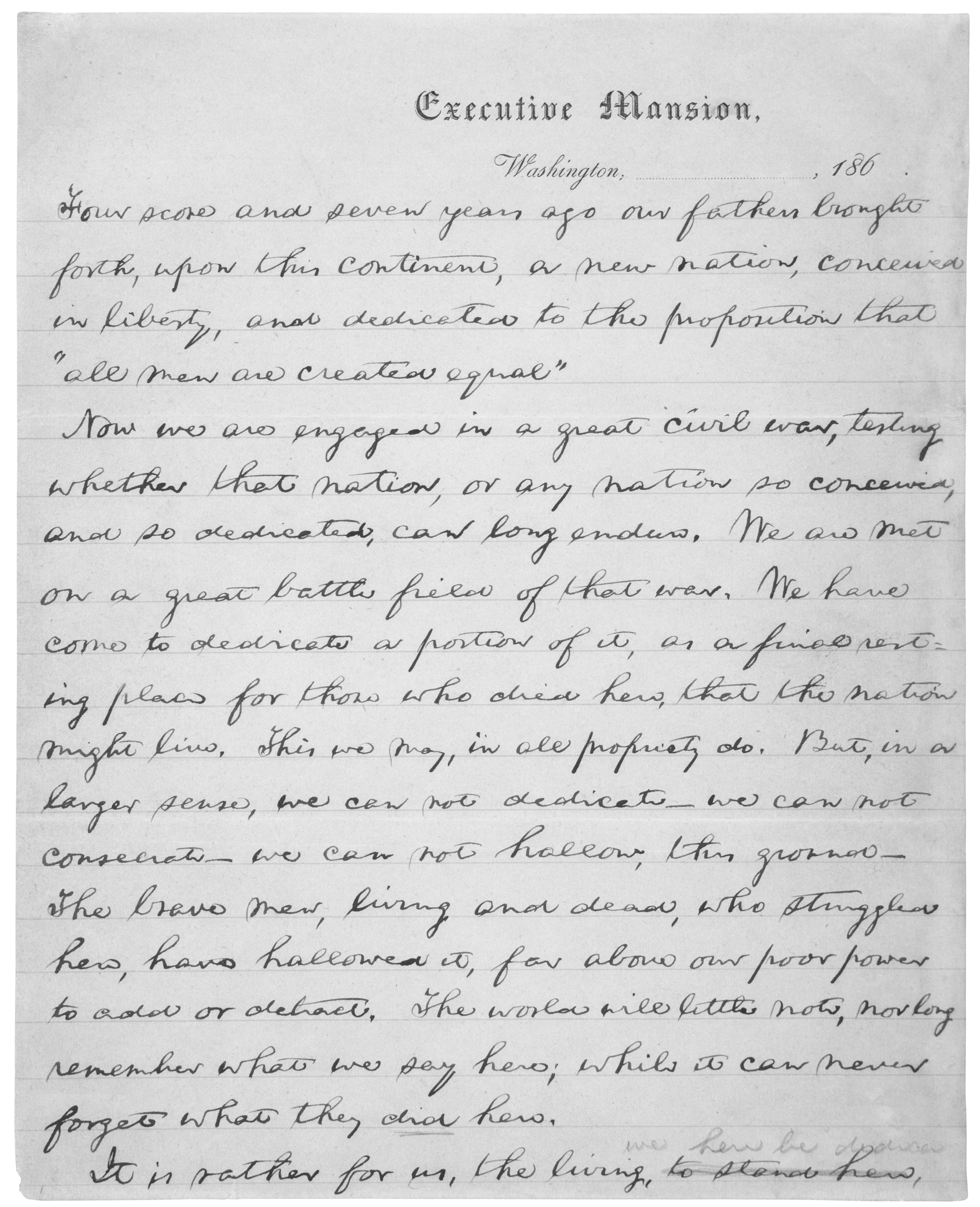

Lincoln wrote five different versions of the speech. He wrote most of the first version in Washington, D.C., and probably completed it at Gettysburg. He probably wrote the second version at Gettysburg on the evening before he delivered his address. He held this second version in his hand during the address. But he made several changes as he spoke. The most important change was to add the phrase “under God” after the word “nation” in the last sentence. Lincoln also added that phrase to the three versions of the address that he wrote after the ceremonies at Gettysburg.

Lincoln wrote the final version of the address—the fifth written version—in 1864. This version also differed somewhat from the speech he actually gave, but it was the only copy he signed. It is carved on a stone plaque in the Lincoln Memorial.

Loading the player...Gettysburg Address

Many false stories have grown up about this famous speech. One story says that the people of Lincoln’s time did not appreciate the speech. But the reaction of the nation’s newspapers largely followed party lines. Most of the newspapers that backed the Republican Party, the party to which Lincoln belonged, liked the speech. A majority of the newspapers that supported the Democratic Party did not. Edward Everett, the principal speaker at the dedication, wrote to Lincoln: “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes.”