Grant, Ulysses S. (1822-1885), served two terms as president of the United States, from 1869 to 1877. Grant had commanded the victorious Union armies at the close of the American Civil War in 1865. His success and fame as a general led to his election as president.

During his military career, Grant led his troops with energy and determination. He developed great confidence in his own judgment and an ability to learn from experience. These traits also characterized Grant’s political career. But the qualities that had brought him military glory were not enough to solve the nation’s problems in the 1870’s. These problems included difficult race relations in the South. Many white Southerners refused to accept Black people as equals after slavery was abolished.

Grant was the first graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point to become president. A quiet, unassuming man, he had an almost shy manner and did not look like a leader. Grant’s presidency was clouded by disgrace and dishonesty. Congressional investigations revealed widespread corruption in both state and local governments. Grant was slow to realize that some people who pretended to be his friends could not be trusted. Several of his major appointees became involved in scandals. But Grant himself was so honest that few historians believe he could have been involved personally.

Grant remembered that Black soldiers had fought to defend the Union. He tried to protect the rights of formerly enslaved people to vote, hold property, and have other privileges of citizenship. He also sought to correct injustices suffered by Indigenous (native) people, then commonly called Indians. But Grant lacked the political skills to achieve these goals of justice and reform.

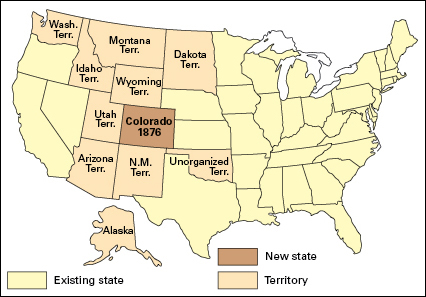

Two months after Grant became president in 1869, the nation’s first transcontinental railroad was completed. In October 1871, the great Chicago Fire killed about 300 people and left more than 90,000 homeless. In 1872, Congress established Yellowstone National Park, the first national park in the United States. Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in 1876. That same year, in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Sioux and Cheyenne warriors killed about 210 men under Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer.

Early life

Boyhood.

Ulysses Grant was born on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio, a village on the Ohio River southeast of Cincinnati. He was the first child of Jesse Root Grant and Hannah Simpson Grant. They named their son Hiram Ulysses Grant but always called him Ulysses or ‘Lyss. In 1823, the family moved to nearby Georgetown, Ohio, where Ulysses’s father owned a tannery and some farmland. Grant’s two brothers and three sisters were born in Georgetown.

Jesse Grant prospered in his tannery. The shy and retiring Ulysses disliked working in the tannery but enjoyed farm work and managing horses. He became an excellent horseman. Ulysses was trustworthy, and his father often sent him on business trips.

Education.

Ulysses attended school in Georgetown until he was 14. He then spent one year at an academy in Maysville, Kentucky, and in 1838, he entered an academy in nearby Ripley, Ohio. Early in 1839, his father learned that a neighbor’s son had been dismissed from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. Jesse asked his congressman to appoint Ulysses as a replacement. The congressman made a mistake in Grant’s name. He thought that Ulysses was the youth’s first name, and his middle name that of his mother’s family. He made out the appointment to Ulysses S. Grant. Ulysses never corrected the mistake. He thought he might be teased about his real initials, “H.U.G.”

Grant was an average student at West Point. He spent much time reading novels and little time studying. But he ranked high in mathematics and made a fine record in horsemanship. Ulysses disliked military life and had no intention of making the Army his career. He considered teaching mathematics in a college.

Early Army career.

Grant graduated from West Point in 1843 and was commissioned a second lieutenant. He was assigned to the Fourth Infantry Regiment, then stationed near St. Louis. There he met Julia Dent (Jan. 26, 1826-Dec. 14, 1902), the sister of a classmate. They fell in love and soon became engaged. The threat of war with Mexico delayed their wedding.

Grant’s regiment went to Louisiana in 1844 and to Texas in 1845. He was in an area claimed by both Mexico and the United States when the Mexican War began in 1846. Grant became regimental quartermaster, in charge of supplies. At Monterrey, he volunteered to carry a message through streets lined with enemy snipers. In 1847, Grant took part in the capture of Mexico City and won praise and promotion for his skill and bravery. He reached the rank of first lieutenant by the end of the war. Grant’s experiences taught him lessons that later helped him during the Civil War.

Grant’s family.

Grant returned to St. Louis as soon as he could leave Mexico. On Aug. 22, 1848, he was married to Julia Dent. She was a devoted wife and gave Grant constant encouragement. Their life together brought them great happiness. The Grants had four children: Frederick Dent (1850-1912), Ulysses S., Jr. (1852-1929), Ellen (Nellie) Wrenshall (1855-1922), and Jesse Root, Jr. (1858-1934).

Army resignation.

Grant remained in the Army after his marriage. He was stationed in Detroit and in Sackets Harbor, New York. Then in 1852, he was ordered to Fort Vancouver in the Oregon Territory. Grant did not take his wife and infant son on the journey because his Army pay would not support a family in the West, where living costs were high. Mrs. Grant and Frederick went to live with Grant’s parents in Ohio.

Fort Vancouver was a lonely post. Grant won promotion to captain in 1853 and was transferred to Fort Humboldt in California. But even a captain’s pay was too small to support a family in the West. Separated from his family, Grant became depressed. Some Army officers gossiped that he had started to drink heavily. Several times in later years, Grant’s critics charged that he drank too much. But no formal proof was ever offered. In 1854, Grant resigned from the Army and settled with his family in St. Louis.

Business failures.

For the next six years, Grant’s life was one of failure. Mrs. Grant’s father gave her a farm near St. Louis, and Grant built a cabin there that he named Hardscrabble. Grant liked farming, but he failed because crop prices were low and his health was poor. He sometimes peddled firewood in St. Louis.

In 1859, Grant sold the farm and moved to St. Louis. A relative gave him a job in a real estate office, but Grant could not collect rents. He next obtained, and then lost, a job in the U.S. Customs House. His father had opened a leather goods store in Galena, Illinois. Grant’s two younger brothers operated the store. In 1860, Grant’s father offered him a $50-a-month job as a clerk. He accepted, but he showed no interest in becoming a storekeeper.

Civil War general

Return to the Army.

Grant was almost 39 years old when the Civil War began in 1861. Grant had owned an enslaved Black man, but he freed him in 1859 and strongly opposed secession. As soon as the war broke out, Grant knew he had a duty to fight for the Union.

After President Abraham Lincoln called for Army volunteers, Grant helped drill a company that was formed in Galena. Then he went to Springfield, the state capital, and worked for the Illinois adjutant general. Grant asked the federal government for a commission as colonel, but his request was ignored. Two months later, Governor Richard Yates appointed him colonel of a regiment that became the 21st Illinois Volunteers. Grant led these troops on a campaign against Confederates in Missouri.

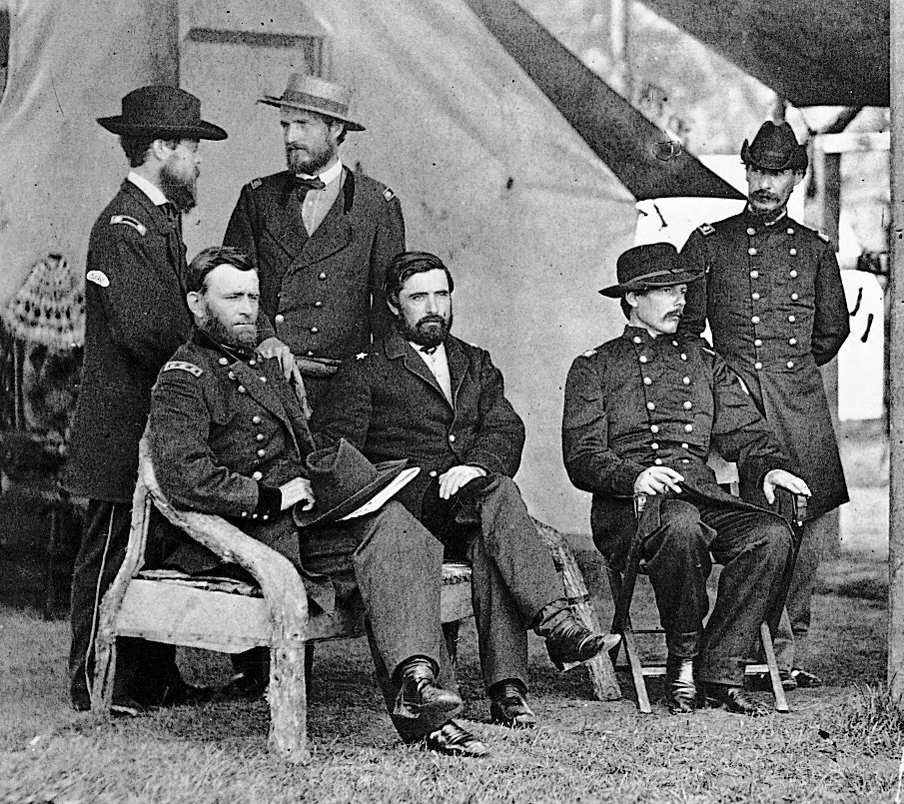

During two months of campaigning, Grant refreshed his memory about handling troops and supplies. Upon the recommendation of Elihu B. Washburne, an Illinois congressman, President Lincoln appointed Grant a brigadier general in August 1861. Grant selected a young Galena lawyer, John A. Rawlins, to serve on his staff. Rawlins soon became Grant’s closest adviser, critic, friend, and defender.

“Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

Steadily, Grant revealed the qualities of a great military commander. He took the initiative, fought aggressively, and made quick decisions. Grant established his headquarters at Cairo, Illinois, in September 1861. He soon learned that Confederate forces planned to seize Paducah, Kentucky. Grant ruined this plan by occupying the city. On Nov. 7, 1861, his troops drove the Confederates from Belmont, Missouri, but the enemy rallied and retook the position.

In January 1862, Grant persuaded his commanding officer, General Henry W. Halleck, to allow him to attack Fort Henry, on the Tennessee River. As Grant’s army approached Fort Henry, most of the Confederates withdrew. A Union gunboat fleet, sent ahead to aid Grant, captured the fort easily. On his own initiative, Grant then lay siege to nearby Fort Donelson. When the fort commander asked for terms of surrender, Grant replied: “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.” The Confederate commander realized he had no choice but to accept what he called Grant’s “ungenerous and unchivalrous” demand. Northerners joyfully declared that Grant’s initials, U. S., stood for “Unconditional Surrender.” Grant was promoted to major general.

On April 6, 1862, the Confederates opened the Battle of Shiloh by launching a surprise attack on Grant’s forces at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee. The Union troops barely held off the enemy until reinforcements arrived. Grant’s resourcefulness helped prevent defeat at Shiloh. But he came under a great deal of criticism for the heavy losses his army suffered, and he nearly lost his command.

Persistence brought Grant a great victory at Vicksburg, Mississippi. All through the winter of 1862-1863, his troops advanced against this key Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. In May 1863, Grant defeated a Confederate army and then besieged Vicksburg. On July 4, 1863, the Confederates surrendered.

Grant’s willingness to make decisions saved the Union forces that were under siege at Chattanooga, Tennessee. Grant was given command of all Union forces in the West in October 1863. He immediately went to Chattanooga and found that plans had been made for breaking the siege. He put the plans into effect at once. On Nov. 25, 1863, Grant’s troops won a sweeping victory.

Grant in command.

Grant succeeded consistently in the West while Union generals in the East were failing. Early in 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general and put him in command of all Union armies. Grant went to Virginia and began a campaign against the forces of General Robert E. Lee.

Grant’s troops suffered severe losses in several battles as he forced Lee to retreat slowly toward Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. Many critics in the North called Grant a “butcher” because he lost so many men. During a bloody battle at Spotsylvania Court House in May 1864, Grant declared: “I … purpose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.” Actually, it took all summer, fall, and winter.

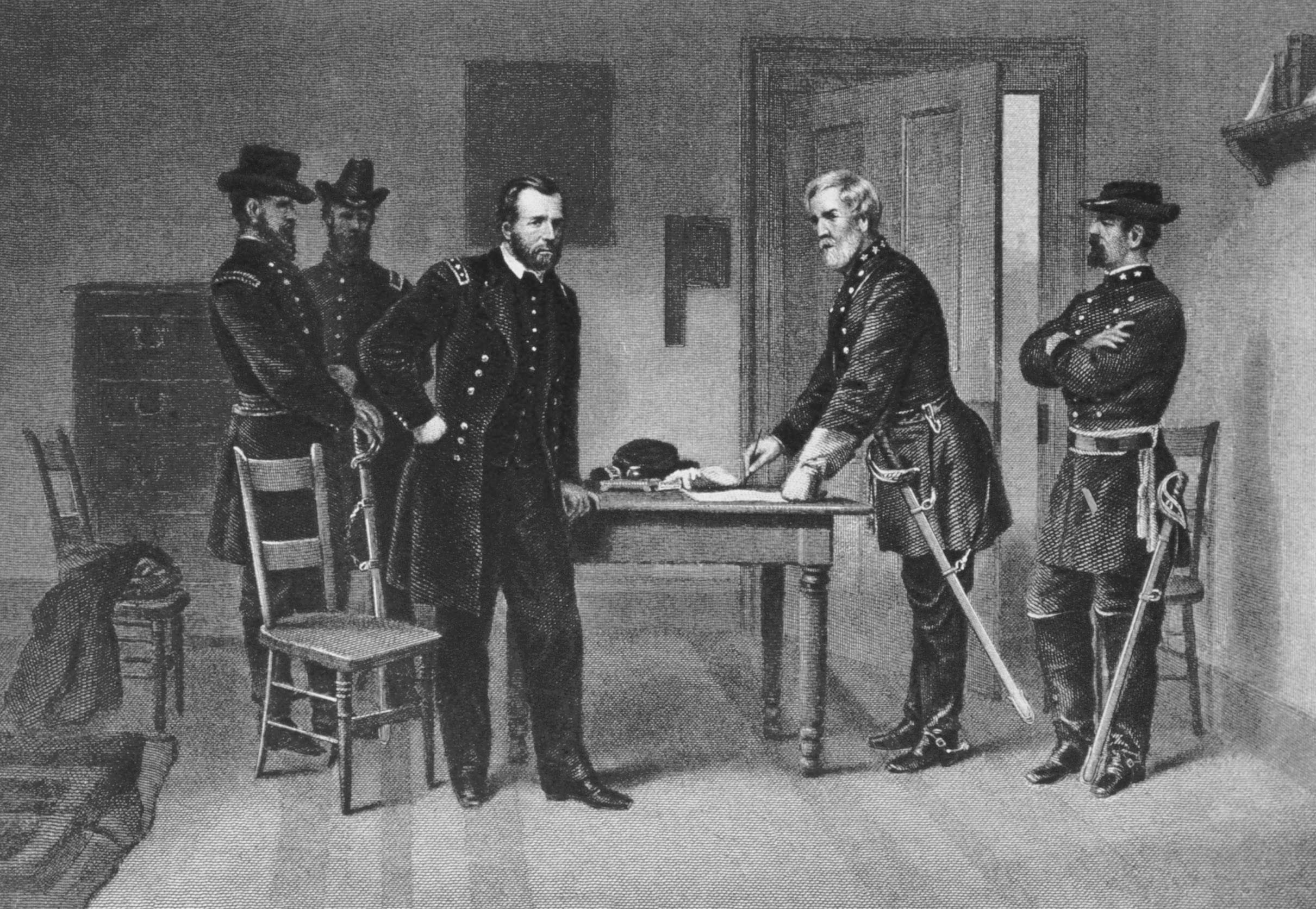

The fierce pressure of the Union Army forced Lee to abandon Richmond early in April 1865. Grant quickly pursued him, and Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Grant released Lee and his soldiers on their honor and allowed the men to keep their horses “for the spring plowing.”

National hero.

Grant’s victory won him great popularity in the North. Southerners appreciated his generous terms to Lee. After the Civil War, a bitter conflict developed between President Andrew Johnson and a group of Republicans in Congress. This group, called the Radical Republicans, demanded harsh treatment of the former enemy and strict protection of the civil rights of Black citizens. President Johnson favored a mild Reconstruction program. He was more concerned with the constitutional rights of states than with the rights of formerly enslaved people.

Grant soon began to believe that Johnson’s policies permitted the Southern States to restrict the rights of Black people. Grant was also disturbed by what he felt was Johnson’s interference with military commanders who were sent into the South to carry out Reconstruction policies.

In 1867, Johnson removed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and appointed Grant to replace him. But the Senate refused to approve the dismissal of Stanton. Grant gave up the office to Stanton and broke with Johnson publicly. Grant then gave his full support to the Republicans.

Election of 1868.

The Republicans badly needed a popular hero for their presidential candidate in 1868. The Democratic Party still controlled many large Northern states that had a great percentage of the electoral votes. Delegates to the Republican National Convention nominated Grant unanimously on the first ballot. They chose speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax of Indiana for vice president. The Democrats nominated former Governor Horatio Seymour of New York for president and former Representative Francis P. Blair, Jr., of Missouri as his running mate. Grant defeated Seymour by a decisive majority of the electoral votes.

Grant’s first administration (1869-1873)

Inauguration.

In his inaugural address on March 4, 1869, Grant admitted that he had no political experience. But he promised that he would not be ruled by professional politicians. “The office has come to me unsought,” he said. “I commence its duties untrammeled.” Grant’s selections for his Cabinet showed his independence from the Republican Party. He did not consult party leaders about his appointments. For other government offices, Grant chose personal friends and army officers. He also appointed some relatives.

Reconstruction policies.

Grant’s administration worked to bring the North and South closer together. It helped persuade Congress to pardon many former Confederate leaders and tried to limit the use of federal troops stationed in the South.

Grant also tried to maintain the rights of Black people in the South. He used federal troops to protect Black people from the Ku Klux Klan and other white groups that organized in the South to keep Black citizens from voting. In 1870 and 1871, Congress passed three force bills to enforce the voting rights of Black people.

Political corruption

continued at all levels of government during Grant’s terms in office. In the South, Black officeholders and Northern adventurers known as carpetbaggers controlled some state governments. Some of these state governments were corrupt. In Northern cities, political machines such as the Tweed Ring in New York City made huge profits from graft on city contracts. Scandals came to light even in the federal government. President Grant himself was honest, but some of his appointees were men of low standards.

Part of the reason for the low state of public morality was the spoils system, which gave great power to politicians. Under this system, successful political candidates rewarded their supporters by giving them government jobs. Many incapable or dishonest persons received high government positions. Grant tried to change the system and urged Congress to adopt measures that would bring a merit system into government service. But Congress refused to appropriate money for a civil service commission that would regulate government jobs. The scandals that soon developed showed the need for civil service reform.

One scandal began during the summer of 1869. Jay Gould, James Fisk, and other financial speculators tried to corner (gain control of) the gold market by buying all the gold available in New York City. They planned to force bankers and businessmen to buy gold from them at highly inflated prices. The only way this corner on the gold market could be broken was by having the federal government sell some of its own gold. But Grant’s brother-in-law, Abel R. Corbin, assured the speculators that he could persuade the president not to permit the sale of government gold. Corbin had no position in the government, but Gould and Fisk accepted his word.

On September 24, which became known as Black Friday, Secretary of the Treasury George S. Boutwell told Grant that the plotters had created a financial panic. Grant then ordered Boutwell to sell government gold, and the panic ended.

Foreign relations.

In 1869, the president of the Dominican Republic offered to sell his country to the United States. Grant’s secretary, General Orville Babcock, signed a treaty of annexation with the republic. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, attacked the treaty and denounced Grant. Most people in the Dominican Republic were of Black African descent. Sumner, a supporter of political rights for Black people, was angered at the thought of a Black republic losing its independence. The Senate rejected the treaty. From then on, Grant regarded Sumner, Carl Schurz of Missouri, and other senators who had opposed him as enemies.

The government had more success in its relations with the United Kingdom. The Alabama and other Confederate warships built in the United Kingdom had destroyed much Northern shipping during the Civil War. The United States claimed that the United Kingdom should pay for this damage. On May 8, 1871, the two countries signed the Treaty of Washington. They agreed to submit the claims to an arbitration commission in Switzerland. The Geneva Tribunal of 1872 ruled that the United Kingdom should pay the United States $151/2 million.

Life in the White House.

Grant took little part in Washington social life except for official appearances. The shy, retiring president reserved warmth and affection for his family. Grant followed a simple daily routine. He arose early and read the newspapers until breakfast. After a short walk, he went to his office, where he carried on official business until 3 p.m. He took a carriage ride or another stroll, ate dinner, and then read newspapers or visited with friends until 10 or 11 o’clock.

In 1874, Grant’s daughter Nellie married Algernon Sartoris, an Englishman. Their wedding in the White House attracted international attention.

Election of 1872.

Grant’s first administration achieved some real success. The national debt was reduced, and the dispute with the United Kingdom over war claims was settled. But Grant offended some politicians and disappointed others who wanted civil service reform. In addition, people who favored free trade opposed the high tariff then in effect.

Discontented Republicans held a convention of their own. They called themselves Liberal Republicans. Senator Schurz and a group of journalists controlled the convention. They nominated Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, for president.

The Democrats also nominated Greeley for president. They hoped, by combining with the Liberal Republicans, to overthrow the corrupt Republican administration. But the Democrats were also corrupt. Their political machines in several big cities had swindled millions of dollars from taxpayers. Also, Greeley had been an ardent Republican and a supporter of the high tariff, which many Democrats opposed. As a result, the Democrats and Liberal Republicans found it hard to cooperate.

Grant’s Republicans presented a united front. Experienced politicians led the party’s campaign. Also, the Republicans knew that they could count on the Black vote of the South. The party renominated Grant for president and named Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts as his running mate. Grant won reelection by a greater majority than he had received in 1868.

Grant’s second administration (1873-1877)

Grant’s second term got off to a bad start as Congress investigated the Credit Mobilier, a construction company owned by leading stockholders of the Union Pacific Railroad. The investigation revealed that many congressmen had taken bribes from the firm to do favors for the Union Pacific. Congress reprimanded several men involved in the scandal.

The Panic of 1873.

In September 1873, several important Eastern banks failed, and a financial panic swept the country. Hardest hit by the panic were bankers, manufacturers, and farmers of the South and West. In an attempt to gain relief, many farmers joined the Greenback Party. This party and other groups demanded an inflation of the nation’s currency to ease the depression.

Under such pressure, Congress passed an inflation bill that would have added $18 million to the paper currency in circulation. But Grant vetoed the bill.

Government frauds.

The voters reacted strongly to the panic and to continued evidence of corruption in government. Grant himself showed poor judgment by accepting personal gifts. The Democrats won a sweeping victory in the congressional elections of 1874. The new Congress investigated the Whiskey Ring, which Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin H. Bristow had uncovered. The investigators found that whiskey distillers in St. Louis and other cities had conspired with tax officials to rob the government of excise taxes. The investigators also charged that Grant’s secretary, General Babcock, had protected the ring from exposure. Grant stoutly defended Babcock, who was cleared of the charges. Many other officials were convicted of defrauding the government.

In 1876, another investigation revealed that Secretary of War William W. Belknap had accepted bribes from a trader at a military trading post in the Indian Territory. Belknap resigned, but the House of Representatives impeached him anyway. He was acquitted on a technicality. Just before the Republican National Convention of 1876, rumors arose of suspicious connections between the Union Pacific Railroad and James G. Blaine, former speaker of the House.

In spite of the growing list of scandals, many Republican leaders wanted to nominate Grant for a third term as president. But Grant refused to run again. In June 1876, the Republicans nominated Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio for president. Hayes won the presidency by a margin of only one electoral vote.

Later years

Grant and his family traveled in Europe and the Far East for more than two years after he left office. He received enthusiastic welcomes wherever he went. When Grant returned home in 1879, he was still highly popular. He rarely occupied a house in Galena, Illinois, that had been given to him by the people of Galena after the Civil War. In 1881, Grant moved to New York City.

At the Republican National Convention of 1880, Grant received strong support. More than 300 delegates voted for him through 36 ballots. Senator-elect James A. Garfield of Ohio won the nomination on the 36th ballot. When Grant learned of Garfield’s nomination, he said: “I feel a great responsibility lifted from my shoulders.”

Grant retired to private life with savings of about $100,000. He invested all his money in the banking firm of Grant & Ward. His son, Ulysses, Jr., was a partner in this company. Grant knew nothing about banking, but his son assured him that Ferdinand Ward was a financial genius. Ward turned out to be dishonest, and the company failed in 1884. The collapse of the company left Grant almost penniless.

To make a living, Grant began writing magazine articles about his war experiences. Soon he announced he would write his memoirs. Mark Twain, the famous American author, became his publisher. The memoirs were a great success and earned Grant’s family about $500,000.

Grant knew he was dying of cancer when he wrote his memoirs. But he was cheered by the good wishes of the American people. In 1885, he moved to Mount McGregor, New York, near Saratoga. Grant died on July 23, 1885, soon after completing his memoirs. His body lies in a tomb in New York City that is officially named the General Grant National Memorial. Mrs. Grant died in 1902 and was buried at his side.