Great Lakes are a group of five lakes in the United States and Canada. The five Great Lakes are Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario. Together, they make up the world’s largest group of freshwater lakes, with 18 percent of the world’s fresh surface water. The Great Lakes also form the most important inland waterway in North America. They were the chief route used by early explorers and settlers of the Midwestern States and Ontario. Later, the transportation offered by the lakes turned the surrounding region into one of the great industrial areas in the United States and Canada.

Of the five lakes, only Lake Michigan lies entirely within the United States. The other four lakes form part of the boundary between the United States and Canada. The Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 provides joint control of the lakes by these two countries.

Among the leading lake ports are Chicago, Milwaukee, and the Port of Indiana on Lake Michigan; Buffalo, Cleveland, Toledo, and Ashtabula on Lake Erie; and Duluth, Superior, and Thunder Bay on Lake Superior. Other ports in the Great Lakes region include Detroit, which lies on a river that connects Lake Huron to Lake Erie, via Lake St. Clair; and Toronto, on Lake Ontario.

How the lakes were formed.

During the last 2 million years, glaciers repeatedly advanced south over the land that is now the Great Lakes region. The glaciers were about 6,600 feet (2,000 meters) thick, and they dug out deep depressions and pushed along great amounts of earth and rocks during their advance. The last advance took place about 25,000 years ago. The last withdrawal, or melting, of the glaciers occurred about 11,000 to 15,000 years ago. Earth and rocks that had piled up blocked the natural drainage of the depressions. Water gradually filled in the depressions and formed thousands of lakes, including the Great Lakes.

Size and elevation.

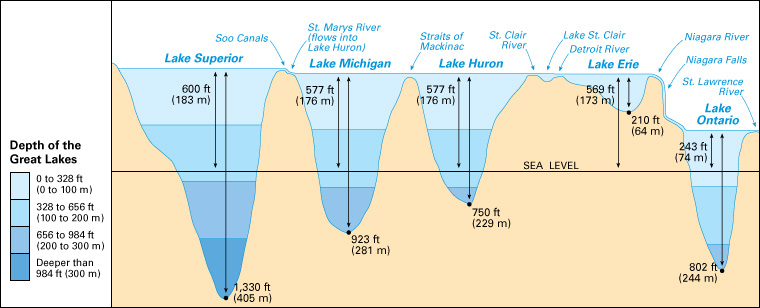

The Great Lakes have a combined area of 94,200 square miles (244,200 square kilometers). Lake Superior, the largest of the lakes, covers 31,700 square miles (82,100 square kilometers). Lake Huron, the second largest of the lakes, has an area of 23,000 square miles (59,600 square kilometers). The third largest lake is Lake Michigan, which covers 22,300 square miles (57,800 square kilometers). Technically, Lake Michigan and Lake Huron are one large lake, connected at the Straits of Mackinac. Lake Erie is the shallowest of the lakes and has an area of 9,900 square miles (25,700 square kilometers). The smallest of the lakes is Lake Ontario, with an area of 7,300 square miles (19,000 square kilometers).

The elevation of the lakes varies greatly. Lake Superior lies 600 feet (183 meters) above sea level, and Lake Ontario lies 243 feet (74 meters) above sea level. The greatest change in water levels between one lake and the next is the 326-foot (99-meter) drop from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario. Part of this difference in water levels can be seen at Niagara Falls.

Drainage.

Many small streams empty into the Great Lakes, but the lakes drain a comparatively small land area. The Great Lakes can be thought of as a series of deep pools connected by narrow channels. From Lake Superior to Lake Ontario, the elevations drop. The waterflow follows that same general direction, from Lake Superior southeastward. In addition, each lake gains water from rain, snow, and runoff from surrounding land.

Each of the Great Lakes loses water by evaporation and by flow to a downstream lake or a connecting river. If rainfall is much greater than evaporation, lake levels rise. All the water in the lakes drains into the St. Lawrence River, except for a small amount that goes down the Chicago River. The course of the Chicago River was turned away from Lake Michigan in 1900, when the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal was opened.

Water routes to the sea.

Some Great Lakes ports lie over 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) inland, but ships can sail from these ports to any other port in the world. This was made possible by three great sets of canals and locks built by the governments of the United States and Canada. These canals and locks compensate for differences in the water levels of the lakes.

One set of canals and locks is the St. Lawrence Seaway. The seaway extends about 450 miles (724 kilometers) from Montreal to the eastern end of Lake Erie. Its canals and locks enable oceangoing ships to sail from the Atlantic Ocean to Lake Superior. The St. Lawrence Seaway includes a set of canals and locks called the Welland Ship Canal. This section of the seaway lies a short distance west of the Niagara River, and it connects Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. The Welland Ship Canal allows ships to pass around Niagara Falls.

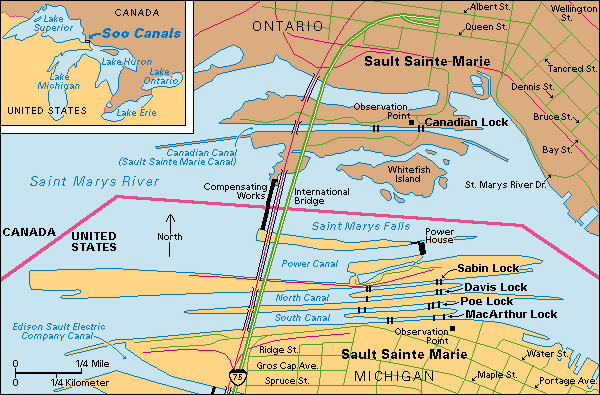

Another set of canals and locks is the Soo Canals. They are on the St. Marys River, which connects Lake Superior and Lake Huron. The canals were built around rapids that occur at a 20-foot (6-meter) drop in the St. Marys River. The route to the sea goes from Lake Huron, through the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair, and the Detroit River, to Lake Erie, through the Welland Canal to Lake Ontario, and down the St. Lawrence to the Atlantic.

Smaller craft may reach the sea by two other routes. One route takes the New York State Canal System from Buffalo to the area near Albany, connecting Lake Erie with the Hudson River and the Atlantic Ocean. The other takes ships from Lake Michigan to the Gulf of Mexico by way of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, through the Illinois River, and down the Mississippi River.

Commerce.

The Soo Canals and the St. Lawrence Seaway are among the busiest canal systems in the world. The Great Lakes have greatly aided the industrial development of the United States and central Canada, especially in the steel industry. These waterways provide a quick route for ships that carry iron ore from ports in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan to steelmaking centers in Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

The Great Lakes also offer the best means for the shipment of the huge wheat crops of western Canada and the northern United States to milling centers in eastern Canada and in Buffalo. Other ships carry coal, copper, flour, and manufactured goods on the lakes.

Ice covers the lake harbors and straits for several months during the winter. Storms can whip up high waves, and ships using the lakes must be strong and safe. Thousands of shipwrecks have occurred in the Great Lakes, many in the November gales (winds). One famous wreck was the Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank on Lake Superior on Nov. 10, 1975.

Changes in lake levels

have a significant impact on the lakes and nearby areas. High water levels, combined with high waves during storms, can cause flooding and erosion of the shoreline. Low water levels can create problems for wildlife, shipping, and hydroelectric power production.

A series of wet years contributed to historically high water levels on the lakes in the early 1970’s, the mid-1980’s, and the late 2010’s and early 2020’s. Historically low water levels occurred in the mid-1960’s, the 2000’s, and the early 2010’s.

Water quality.

Industrial wastes, sewage, and other wastes have polluted the Great Lakes since the mid-1800’s. To remedy pollution and to control water use, the United States and Canada set up the International Joint Commission (IJC) in 1909. The IJC examines the uses of the boundary waters, undertakes studies, and settles disputes on boundary waters issues.

In the late 1960’s, concern about pollution, particularly in Lake Erie, grew. Phosphorus, sewage, and fertilizer wastes had caused algae growth that made beaches messy and smelly. In 1972, the United States and Canada signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. Improvements resulted, especially a reduction in the levels of phosphorus dumped into the lake.

Water quality issues continue today. High levels of E. coli bacteria—caused by storm sewer runoff or sewage overflows—have caused health concerns and beach closures. Other pollutants, such as toxic chemicals and metals, are also a problem. These substances may reach the lakes by air, from such sources as the spraying of insecticides and the burning of wastes and fuels. Still other pollutants may enter the lakes from previously contaminated river sediments, or from surface and ground- water contamination. These pollutants may have caused diseases in some Great Lakes fish. High levels of mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB’s), a type of harmful chemical, have caused the Great Lakes states and Ontario to suggest that people avoid eating certain fish and limit consumption of others.

A cleanup program focused on Environmental Protection Agency “Superfund” sites in the United States has systematically cleaned up and removed sources of toxic sediments. Many contaminated sites remain, however.

Invasive species

—animals, plants, and other living things that spread rapidly in new environments—have become a problem for the Great Lakes. A number of exotic species have reached the lakes through the St. Lawrence Seaway and through ballast (water kept in the hold of a ship) from foreign ships. Many of these species have had a harmful impact on native species.

Some of the more damaging invasive species include sea lampreys, quagga and zebra mussels, alewives, spiny and fishhook water fleas, European ruffe, round gobies, and a virus that causes a fish disease called viral hemorrhagic septicemia (VHS). Invasive Asian carp species have been found in waterways that connect to the Great Lakes, and states have installed underwater electric barriers to prevent their spread. The environmental and economic problems caused by invasives have led to efforts to regulate ballast disposal. Some critics have also called for limits on external shipping on the Great Lakes.