Hand is the end of a forelimb, or arm. Hands are specially constructed for taking hold of objects. True hands have opposable thumbs, or thumbs that can be moved against the fingers. This action makes it possible to grasp things in the hand and make many delicate motions. Human progress would have been hampered without the use of opposable thumbs. To help understand the work that thumbs do, try to pick up a pen while keeping your thumb motionless alongside your hand.

Hands are also used to touch and feel things. The human hand contains at least four types of nerve endings that make the fingers and thumbs highly sensitive. Blind persons rely entirely on their sense of touch when reading. They run their fingers over the raised letters of Braille books.

The human hand also helps people communicate with each other—as in the sign language of the North American Indians or that of deaf persons. In these sign languages, gestures and positions of the hand and fingers represent words or phrases. Hands convey familiar expressions and ideas. Well-known examples include the clenched fist of anger, the raised palm of peace, the “V” for victory or for peace, the “thumbs down” for disapproval, and the gesture for hitchhiking.

Parts of the hand.

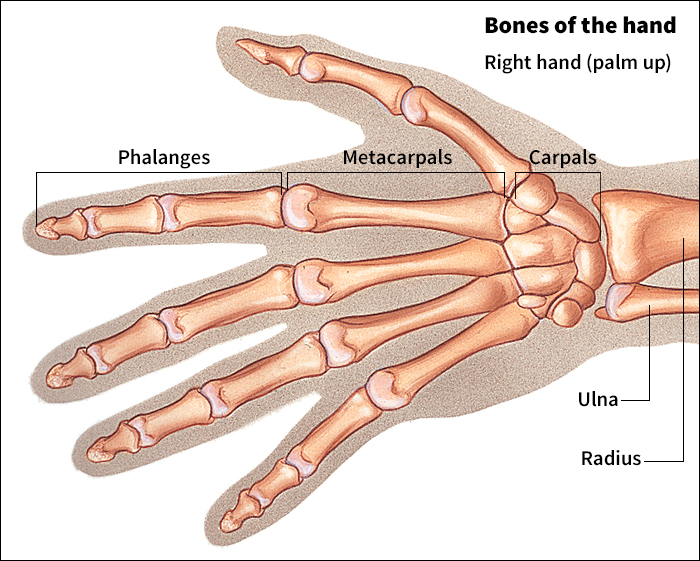

The human hand consists of the carpals (wrist bones), the metacarpals (palm bones), and the phalanges (four fingers and thumb). There are 27 bones in the hand. Eight carpal bones make up the wrist. They are arranged roughly in two rows. In the row nearest the forearm, starting from the thumb side, are the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform bones. In the second row are the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate bones. Five long metacarpal bones make up the palm. They connect the wrist with the fingers and thumb. Each of the four fingers contains three slender phalanges. However, the thumb contains only two phalanges.

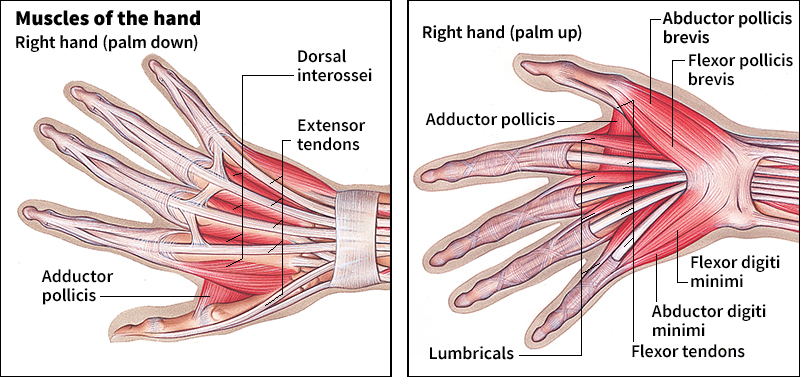

Thirty-five powerful muscles move the human hand. Fifteen are in the forearm rather than in the hand itself. This arrangement gives great strength to the hand without making the fingers so thick with muscles that they would be difficult to move. Near the wrist, the muscles become strong, slender cords called tendons. The tendons run along the palm and back of the hand to the joints of the fingers. When the muscles on the palm side of the forearm contract, the fingers close. When the muscles on the back of the forearm contract, the fingers open. Twenty muscles within the hand itself are arranged so that the hand and fingers can make a variety of precise movements.

Animal hands.

In many animals, part of the forelimb corresponds to the human hand. These parts have the same basic arrangement of bones and muscles whether the animal uses them to dig, fly, swim, or run.

No animal “hand” has more than five digits. Animals have many kinds of “hands.” The mole’s short, chunky “hand” is ideally suited to act like a shovel in digging tunnels. The bat’s forelimb is a wing, with a web of skin spread between the fingers. The bird’s “hand” is also a wing. Phalanges and metacarpals support the wing. The seal’s “hand” is its flipper. The bones have fused, or grown together, and they form a broad, flat paddle that is useful for swimming. The “hand” of the horse is constructed so that the animal stands on its middle finger. Through millions of years of development, the middle finger has become stronger and longer. This middle finger is well adapted to running. The horse’s other fingers have become quite small or have disappeared.