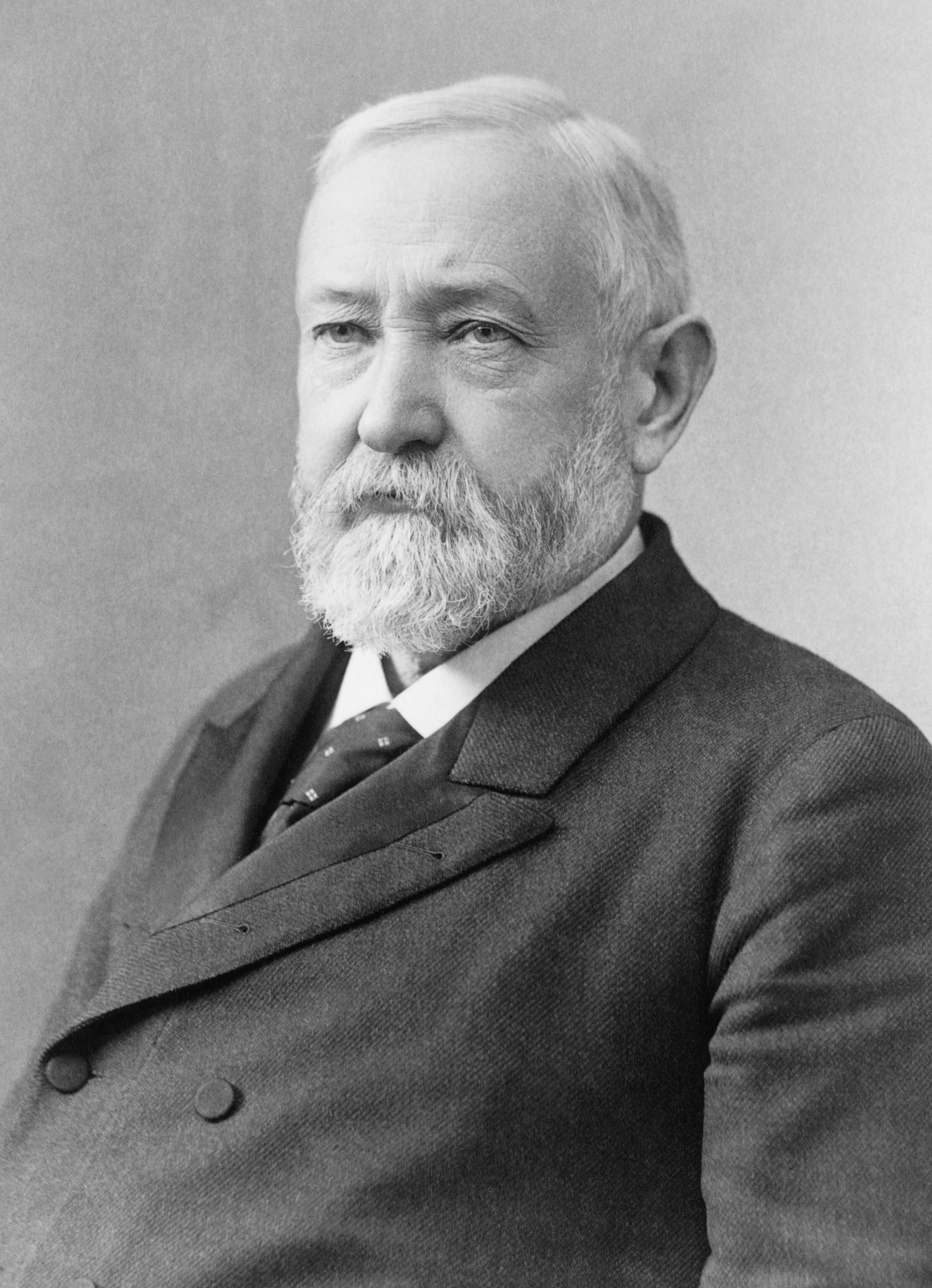

Harrison, Benjamin (1833-1901), was the only grandson of a president who also became president. He defeated President Grover Cleveland in 1888, but Cleveland regained the presidency by beating Harrison in 1892.

Harrison’s grandfather was William Henry Harrison, the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe. William Henry Harrison had died of pneumonia in 1841 after only one month as president. Benjamin Harrison, like his grandfather, was an Army commander and a United States senator before being elected to the presidency.

Harrison did more than any other president to increase respect for the flag of the United States. By his order, the flag waved above the White House and other government buildings. Harrison also urged that the flag be flown over every school in the land.

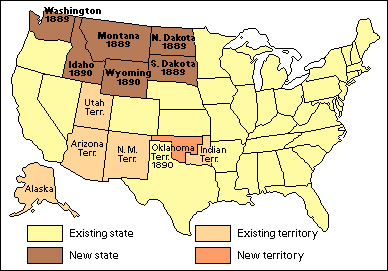

Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act and other landmark laws during Harrison’s administration, and provided for the building of a two-ocean navy of steel ships. The American frontier disappeared as pioneers took over the last unsettled areas of the West. Six new states joined the Union.

Early life

Childhood.

Benjamin Harrison was born on Aug. 20, 1833, on his grandfather’s farm in North Bend, Ohio. He was named for his great-grandfather, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Ben was the second of the 10 children of John Scott Harrison and Elizabeth Irwin Harrison. His father, a farmer, served two terms in Congress. Ben, a short, stocky boy, spent his youth on the farm.

Education.

Harrison attended Farmers’ College in a Cincinnati suburb for three years. While a freshman, he met his future wife, Caroline Lavinia Scott (Oct. 1, 1832-Oct. 25, 1892). She was the daughter of John W. Scott, the president of a women’s college in the town. In 1849, Scott moved his college to Oxford, Ohio. The next year Harrison followed the Scotts to Oxford, where he graduated from Miami University in 1852.

Harrison’s family.

Harrison and “Carrie” Scott were married in 1853. They had two children, Russell Benjamin (1854-1936) and Mary (1858-1930).

Lawyer.

After reading law with a Cincinnati firm, Harrison was admitted to the bar in 1854. He moved to Indianapolis that same year. In his first big court case, a single candle stood on the table where Harrison had his notes. He vainly shifted the candle back and forth to get more light, but finally threw the notes away. Harrison not only discovered that he was a good speaker, but he also won the case. While he was starting out as a lawyer, Harrison bolstered his income by earning $2.50 a day as court crier, proclaiming the orders of the court.

Political and public activities

Political beginnings.

As the son of a Whig congressman and the grandson of a Whig president, Harrison had a name that was familiar to many voters. Although his father wrote him that “none but knaves should ever enter the political arena,” Harrison ran successfully for city attorney of Indianapolis in 1857. He became secretary of the Republican state central committee in 1858. He was elected reporter of the state supreme court in 1860 and reelected four years later.

A deeply religious man, Harrison taught Sunday school. He became a deacon of the Presbyterian Church in 1857 and was elected an elder of the church in 1861.

Army commander.

In 1862, Governor Oliver P. Morton asked Harrison to recruit and command the 70th Regiment of Indiana Volunteers in the American Civil War. As he and Morton walked down the steps of the state Capitol, Harrison recruited his first soldier—his former law partner, William Wallace.

Colonel Harrison molded his regiment into a well-disciplined unit that fought in many battles. His soldiers called him “Little Ben” because he was only 5 feet 6 inches (168 centimeters) tall. A fearless commander, Harrison rose to the rank of brigadier general.

National politics.

After the war, Harrison won national prestige as a lawyer. In 1876, he ran unsuccessfully for the office of governor of Indiana. President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him to the Mississippi River Commission in 1879, and he held this post until 1881. Harrison turned down a post in the Cabinet of President James A. Garfield because he had been elected to the U.S. Senate in January 1881.

During his term in the Senate, Harrison supported civil service reform, a protective tariff, a strong navy, and regulation of railroads. He criticized President Grover Cleveland’s vetoes of veterans’ pension bills. Indiana’s Democratic legislature defeated Harrison’s bid for a second term by one vote. At that time, the state’s legislature rather than the general voting public elected senators.

Election of 1888.

James G. Blaine, who had lost the 1884 presidential election to Cleveland, refused to run in 1888. The Republicans nominated Harrison, because of his war record, his popularity with veterans, his ability to express the Republican Party’s views, and the fact that he lived in Indiana. The Republicans hoped to win Indiana’s 15 electoral votes, which had gone to Cleveland in the previous presidential election. Levi P. Morton, a New York City banker, was nominated for vice president. The Democrats renominated Cleveland and named Allen G. Thurman, a former Ohio senator, as his running mate.

Harrison, in a “front porch” campaign from his home, supported high tariffs. Cleveland called for lower tariffs, but did not campaign actively because he felt it was beneath the dignity of the presidency.

In the election, Harrison trailed Cleveland by more than 90,000 popular votes. But, by carrying Indiana, New York, and other “doubtful states,” Harrison won the election in the Electoral College.

Harrison’s administration (1889-1893)

The Republicans held a majority in both houses of Congress during the first half of Harrison’s term. As a result, the president won enactment of his legislative program. In the congressional elections of 1890, the Democrats won control of the House of Representatives, and the Republican majority in the Senate was reduced to six. The change partly reflected public disapproval of vast congressional appropriations, which reached almost a billion dollars. When Democrats accused the Republicans of wastefulness, Thomas B. Reed, speaker of the House, replied, “This is a billion-dollar country!”

Domestic affairs.

During the campaign, Harrison had promised to extend the civil service law to cover more jobs. He kept his promise by increasing the number of classified positions from 27,000 to 38,000.

The four most important laws of Harrison’s administration were all passed in 1890.

The Sherman Antitrust Act.

During the period of rapid industrialization in the late 1880’s, many corporations formed trusts that controlled market prices and destroyed competition (see Antitrust laws). Farmers and owners of small businesses demanded government protection from these trusts. The Sherman Antitrust Act, fulfilling one of Harrison’s campaign pledges, outlawed trusts or any other monopolies that hindered trade.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act

met another demand of farm voters. Farm prices were falling, and farmers asked the government to put more money into circulation, either paper money or silver coins. Farmers felt that this action would increase farm prices and thus make it easier for farmers to pay their debts. The owners of the silver mines naturally favored a demand that would boost their own profits. The Sherman Silver Purchase Act increased the amount of silver that could be coined. The government purchased this silver and paid for it with Treasury notes that could be redeemed either in silver or gold. Because most people chose to redeem their notes in gold, the fear of a drain on the Treasury’s gold reserves helped cause a financial panic in 1893.

The McKinley Tariff Act

was designed mainly to protect U.S. industries and their workers from foreign competition. Its sponsors tried to make the law attractive to farmers by raising tariffs on imported farm products. But the McKinley Tariff Act set tariffs at record highs, and farmers regarded it chiefly as a benefit to business.

The Dependent Pension Bill

broadened pension qualifications to include all Civil War veterans who could not perform manual labor. The cost of pensions soared from $88 million in 1889 to $159 million in 1893.

International affairs.

Harrison launched a program to build a two-ocean navy and expand the merchant marine. Both actions helped shape the new and vigorous foreign policy developed by Harrison and Secretary of State James G. Blaine.

Latin America.

In 1889, the first Pan-American Conference met in Washington. The delegates began expanding the meaning of the Monroe Doctrine by promoting cooperation among the nations. The Pan American Union was created at this conference.

Trade

with other nations was being threatened by U.S. tariffs that constantly grew higher. Harrison began to negotiate reciprocal trade agreements. This was an attempt to compromise between manufacturers who wanted free competitive markets and those who favored protective tariffs.

Hawaii.

Early in 1893, Queen Liliuokalani had lost her throne in a revolution led by American planters. The new Hawaiian government asked the United States to make Hawaii a territory. Harrison had been defeated for reelection the previous November, but he rushed a treaty of annexation to the Senate before his term ended. Cleveland returned to the presidency before the Senate could act on the treaty, and he withdrew it. He declared that the whole affair was dishonorable to the United States.

Other developments.

The Harrison administration also settled a number of old quarrels. The government agreed to arbitrate the long-standing dispute with the United Kingdom over fur seals in the Bering Sea (see Bering Sea controversy). In 1889, a quarrel over the ownership of the Samoa Islands seemed likely, and the United States joined Germany and England in establishing a protectorate over the islands. In 1892, Congress passed the Oriental Exclusion Act, which long remained a sore spot in America’s relations with China and Japan (see Oriental Exclusion Acts).

Life in the White House

was thoroughly photographed for the first time during Harrison’s term. Electric lights and bells were installed in the mansion in 1891. But the Harrisons, fearing shocks, often used the old-style gas lights, or asked the White House electrician to turn the switches on and off.

Despite poor health, Mrs. Harrison worked hard as official hostess. She once told a reporter that “there are only five sleeping rooms and there is no feeling of privacy.” Members of the Harrison family usually occupied these rooms. Mrs. Harrison’s father lived in the White House, as did Mrs. Mary Dimmick, a widowed niece who served as her secretary. The Harrisons’ daughter, Mrs. Mary McKee, and her husband and two children lived there most of the time. Mrs. Harrison devised a plan for expanding the White House, but Congress would not approve funds for anything more than refurbishing the building.

Bid for reelection.

The Republicans renominated Harrison in 1892 and chose Whitelaw Reid, U.S. minister to France and editor of the New York Tribune, as his running mate. The Democrats again nominated Cleveland for president and named Adlai E. Stevenson, a former Illinois congressman, for vice president.

Discontented farmers turned from the Republicans to the new Populist Party, which had been formed in protest against falling farm prices (see Populism). Angry factory workers deserted the Republicans, charging hostile interference by the federal and state governments in the bloody Homestead Strike and other labor disputes. Opposition to the McKinley Tariff Act also helped defeat Harrison, who received 5,182,690 popular votes to Cleveland’s 5,555,426. The Populist candidate, James B. Weaver, received more than a million votes. This gave Cleveland 277 electoral votes to Harrison’s 145. Weaver received 22 electoral votes.

Personal tragedy struck Harrison just two weeks before the national elections of 1892. His wife died on October 25.

Later years

Harrison returned to Indianapolis and the practice of law. In 1896, he married Mrs. Dimmick (April 30, 1858-Jan. 5, 1948), who had nursed his wife during her last illness. They had one child, Elizabeth (1897-1955).

In 1897, Harrison wrote This Country of Ours, a book about the federal government. In 1899, he represented Venezuela in the arbitration of a dispute with the United Kingdom over the British Guiana boundary. Harrison died in his home on March 13, 1901, and was buried in Indianapolis.