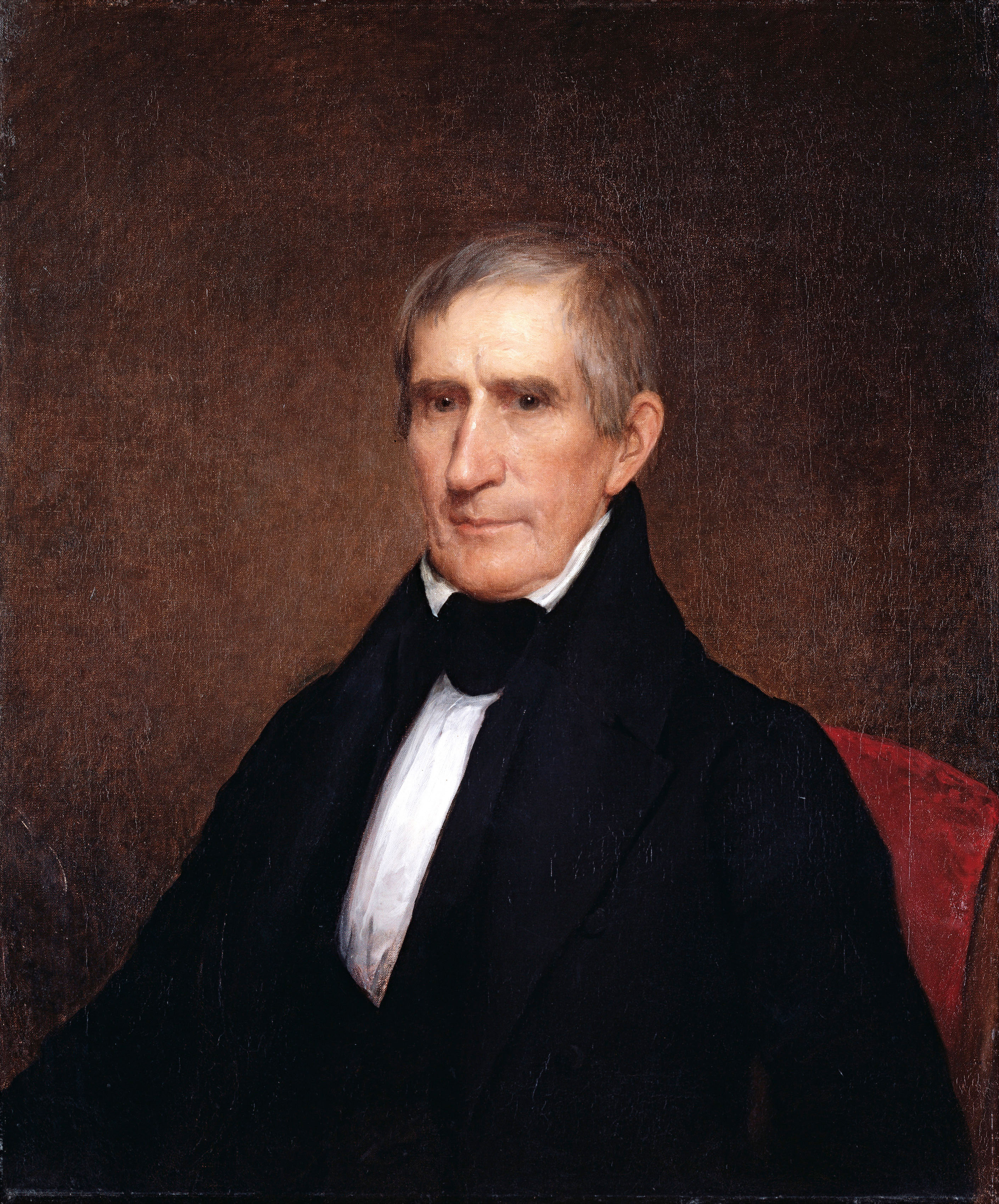

Harrison, William Henry (1773-1841), served the shortest time in office of any president in American history. He caught cold the day he was inaugurated president, and he died 30 days later. Harrison was the first president to die in office.

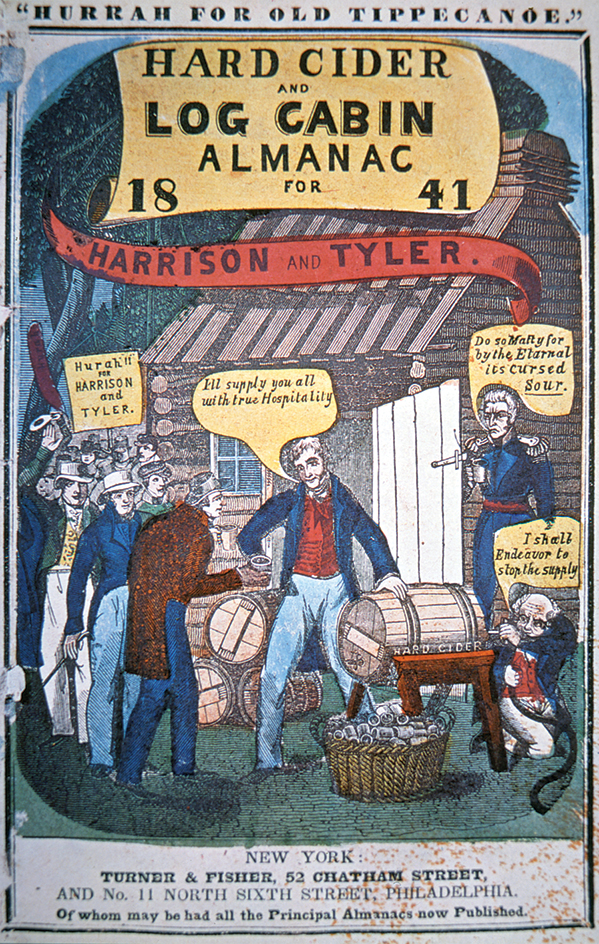

Harrison is best remembered as the first half of the catchy political campaign slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler too.” He had received the nickname “Tippecanoe” after defeating several Indian tribes in 1811 at the Battle of Tippecanoe. The Whig Party first ran Harrison for president against Democrat Martin Van Buren in 1836. He lost. Then they ran him again in 1840. Using his colorful military career as their theme, the Whigs turned the campaign of 1840 into a circus. This time, Harrison defeated President Van Buren. Harrison was the first Whig president, and the only chief executive whose grandson (Benjamin Harrison) also became president.

During his brief term, Harrison showed an interest in running the government efficiently. He made surprise visits to government offices to check on the workers. Upon Harrison’s death, his office fell to Vice President John Tyler, a former Virginia Democrat. The Whigs had nominated Tyler to attract Southern votes. But when Tyler became president, the Whigs unhappily learned that he still believed in many of the ideas of the Democratic party. He vetoed bill after bill and destroyed the Whig program in Congress.

Early life

William Henry Harrison was born on Feb. 9, 1773, at Berkeley, his father’s plantation in Charles City County, Virginia. He was the youngest of seven children, four girls and three boys. His parents, Benjamin and Elizabeth Bassett Harrison, came from prominent Virginia families. The elder Harrison had served in both Continental Congresses and signed the Declaration of Independence.

William received his early education at home. He entered Hampden-Sydney College in 1787 and later enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania to study medicine. After his father died in 1791, Harrison dropped medicine and joined the Army. George Washington, a friend of his father, approved this decision.

Military and political career

Soldier.

Harrison served in early American wars against the Indians and rose to the rank of lieutenant. In 1794, he developed a plan which led to an American victory on the Great Miami River. He was promoted to captain and given command of Fort Washington, Ohio.

Harrison’s family.

While at Fort Washington, Harrison met and married Anna Symmes (July 25, 1775-Feb. 25, 1864). She was the daughter of John C. Symmes, a judge and wealthy land investor. The Harrisons had six sons and four daughters. Six of the children died before Harrison became president.

Entry into politics.

Harrison resigned his Army commission in June 1798, and President John Adams appointed him secretary of the Northwest Territory. In 1799, Harrison was elected the first delegate to Congress from the Northwest Territory. In Congress, Harrison persuaded the lawmakers to pass a bill that divided western lands into sections small enough for even a poor person to buy.

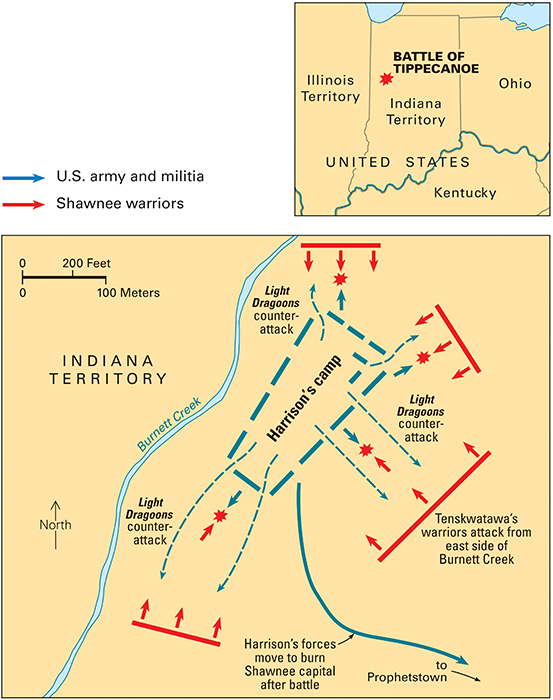

In 1800, Adams named Harrison governor of the Indiana Territory, a post he held for 12 years. As governor, Harrison sought to protect the welfare of American Indians living in the territory. He banned the sale of liquor to them, and ordered that they be inoculated against smallpox. In 1809, Harrison negotiated a treaty with Indian leaders which transferred about 2,900,000 acres (1,170,000 hectares) of land on the Wabash and White rivers to settlers. Many Indians denounced the treaty. They united under the Shawnee chief Tecumseh and his brother, known as the Shawnee Prophet. Harrison took command of the territorial militia and set out to drive the Indians from treaty lands. On Nov. 7, 1811, Harrison’s outnumbered troops shattered the Indian forces in the Battle of Tippecanoe.

Army commander.

When the War of 1812 began, President James Madison made Harrison a brigadier general in command of the Army of the Northwest. Harrison was promoted to major general early in 1813. In October 1813, his troops won a brilliant victory over combined Indian and British forces in the Battle of the Thames in southern Ontario.

Return to politics.

Harrison again resigned from the Army in 1814 after a quarrel with the secretary of war. He settled on a farm in North Bend, Ohio. In 1816, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives. He was accused of misusing public money while in the Army, but a House investigating committee held the charge false. His name cleared, Harrison returned to Ohio. In 1819, he was elected a state senator. The legislature elected him to the United States Senate in 1825. He resigned in 1828 to accept an appointment from President John Quincy Adams as the U.S. minister to Gran Colombia (now Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, and Venezuela). But the blunt-spoken Harrison lasted about a year in diplomacy. President Andrew Jackson appointed one of his supporters to replace Harrison in 1829.

Elections of 1836 and 1840.

Harrison was one of three Whig Party candidates for the presidency in 1836. The party was a mixture of people with conflicting ideas of government, and Harrison’s supporters felt he could unify the party. He ran surprisingly well, winning 73 electoral votes. Democrat Martin Van Buren won the presidency with 170 electoral votes.

In 1840, the still-divided Whigs tried to broaden their appeal, which had been confined mainly to big eastern cities. They nominated Harrison again and, for vice president, chose John Tyler, a Virginia Democrat.

The Whigs made no attempt to agree on issues or even to adopt a platform. They simply hoped to hang together until they won the presidency. They did this by emphasizing antics rather than issues. Party leaders told Harrison to say “not one single word about his principles or creed.” A Democratic newspaper charged that all Harrison wanted for the rest of his life was a pension, a log cabin, and plenty of hard cider. The Whigs turned this sneer to their advantage by proudly presenting Harrison as “the log cabin, hard cider” candidate. Torchlight parades with cider barrels and log cabins on wagons rolled down streets all over the nation. The Whigs blamed President Van Buren, the Democratic candidate, for the country’s hard times. They contrasted the hungry workers with the aristocratic Van Buren, who they said wore “corsets and silk stockings.” Harrison won by about 147,000 votes but had a huge electoral majority.

Harrison’s administration (1841)

Harrison’s wife became too ill to travel just before he left for Washington, so he was accompanied by his widowed daughter-in-law, Jane Irwin Harrison. She served as White House hostess during his term. It was a cold, rainy day when Harrison gave his inaugural address. Soon after, he caught a cold, which a month later proved fatal.

Harrison spent his energy deciding political appointments. He left the development of a legislative program to Henry Clay, the Whig leader in Congress.

The

Just one week after Harrison took office, the United States faced a serious crisis with the United Kingdom. Over three years earlier, a member of the American crew of the steamboat Caroline had been killed while carrying supplies to Canadian rebels. Much later, police in Buffalo, New York, arrested a visiting Canadian who had been one of the party that attacked the Caroline. The British waited until Van Buren had left office, then demanded the prisoner’s release on threat of war. Harrison turned the problem over to Daniel Webster, who apologized. But tension was not eased until Webster negotiated the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842 (see Webster-Ashburton Treaty ).

Death.

Harrison sought relief from the pressures of his office by attending to minor details of running the White House. One raw March morning, he went out to buy vegetables and suffered a severe chill. The cold he had caught on inauguration day now developed into pneumonia. Harrison died on April 4, 1841, 121/2 hours short of 31 full days in office. He was buried in North Bend, Ohio.