Immigration is the act of moving to a foreign country to live. The act of leaving one’s country is called emigration. Most people find it hard to pull up roots in their native land and move to a different country. But throughout history, countless millions of people have done so. The heaviest immigration worldwide took place from the early 1800’s to the 1930’s. In that period, about 60 million people moved to a new land. Most came from Europe. More than half immigrated to the United States.

Today, improved communications and cheaper transportation make some aspects of migration easier. However, laws designed to control movement across national borders make other aspects of migration more difficult. The United States remains the chief receiving nation. Europe also receives many immigrants, and Asia is the largest source of emigrants.

Causes of immigration

People leave their homeland and move to another country for various reasons. Some emigrate to avoid starvation. Some seek adventure. Others wish to escape unbearable family situations. Still others desire to be reunited with loved ones.

Economic opportunity

—the lure of better land, a better job, or a better life—is the chief reason for international migration. In the 1800’s, for example, the rich prairie land of the United States and Canada attracted many Europeans who wanted to own the land they farmed. In the early 1900’s, Europeans sought work in growing U.S. factories. Today, many professionals emigrate for better opportunities. For example, many computer programmers, doctors, engineers, and scientists have moved from India to the United States and Canada. Often, people who would benefit significantly from migration do not move because they lack the financial resources to do so.

Refugees

are immigrants who flee their countries because of political and religious persecution, political unrest, revolution, war, and such disasters as epidemics and famines. Refugees may apply for asylum in another country. In law, asylum means protection and shelter given by one nation to a person fleeing another nation.

In 1492, Spanish Jews threatened with forced conversion fled Spain. And in the late 1600’s, French Protestants called Huguenots fled France under pressure to convert to Roman Catholicism. Other European powers welcomed the Huguenots, but not the Jews, who were forced to move to the Middle East and North Africa. These historical examples show that not all people emigrating for similar reasons will gain a safe haven.

After World War II (1939-1945), more than 40 million people were estimated to be displaced in Europe. This crisis eventually led to the United Nations’ 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, by which many countries agreed to provide protection to persons fleeing a “well-founded” fear of persecution. Since World War II, the number of refugees worldwide has fluctuated, rising from 1970 to 1992, falling until 2005, then growing sharply. In the early 2000’s, a majority of refugees were from Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Syria.

Most refugees flee to neighboring countries, where they wait and hope for conditions at home to improve. However, continuing conflict often makes return impossible. For this reason, a majority of refugees are found in the developing world. A small minority are resettled abroad in Canada, Europe, and the United States. Because citizens of wealthy countries often are opposed to refugee resettlement, such countries may provide subsidies (financial aid) to poorer nations that house many refugees instead of admitting the refugees themselves.

Effects of immigration

Population movements have mixed effects on countries of origin and destination. For example, emigration can relieve overcrowding in a country, but that country may lose people with valuable skills. Receiving nations gain new workers but may have trouble providing them with education, housing, jobs, or social services.

The effects of population movements on the world economy are difficult to measure. Many immigrants bring valuable skills to their adopted countries. Others acquire such skills in adopted countries, accumulate savings, then return home. Some immigrants establish businesses that trade with their homelands. Many stay permanently in their adopted countries but regularly send money to families back home. Some immigrants return to their native lands after they retire from work.

Some immigrants return home because they find adjusting to a new society too difficult. This process of adjustment is called integration. Many immigrants first settle in a community that includes people from their native land, minimizing language difficulties. In time, most immigrants, and especially their children, begin to integrate. They learn their new country’s language and adapt to its culture. Pluralism describes a type of integration in which immigrants retain their old language and culture. Assimilation occurs when immigrants give up their old language and culture. Successful integration occurs when immigrants and their descendants are accepted by society in the countries where they settle.

Most immigrants find work. They try to give their children the educational and other opportunities not available in their native lands. Many become citizens of their new countries and take part in government and politics.

Immigrants remain citizens of their countries of origin unless they become naturalized. Naturalization is the legal process of gaining citizenship in an adopted country. Naturalization policies and requirements vary among nations. Some governments encourage naturalization and make it relatively easy, while others discourage it and make it more difficult. Applicants for citizenship may be required to reside in a country for a minimum number of years, take a test, or pay fees. Some countries grant citizenship to anybody born within their borders, even if the parents are not citizens or legal residents.

Some immigrants live in their adopted countries for many years without ever becoming citizens or obtaining the government’s permission to stay. These people sometimes are referred to as illegal, undocumented, or unauthorized aliens (noncitizens) or immigrants. They lack the legal documents that officially permit residence in a country. Some immigrants enter a country legally, but later lose their legal status for various reasons.

Immigrants have made enormous contributions to the culture and economy of such nations as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Israel, New Zealand, and the United States. But integration often has proven difficult to achieve. Many of the receiving countries have restricted immigration to maintain a homogeneous society in which all the people share the same cultural, ethnic, and geographic background. Some receiving countries have had policies favoring people from particular areas. For example, from the 1920’s to the 1960’s, the United States had national origins policies that made it easiest for northern Europeans to immigrate. Although some nations’ immigration laws have been relaxed, many immigrants still face challenges in gaining acceptance.

Immigration to the United States

The United States has had four major periods of immigration. The first wave began with the colonists of the 1600’s and reached a peak just before the American Revolution started in 1775. The second major flow of immigrants started in the 1820’s and lasted until an economic depression in the early 1870’s. The greatest inpouring of people took place from the 1880’s to the early 1920’s. A fourth wave began in 1965.

The first wave.

Most of the immigrants who settled in the American Colonies in the 1600’s came from England. Others arrived from France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Scotland, and Wales. Spanish colonists settled in what is today the southwestern United States.

Some colonists sought adventure. Others fled religious persecution. Many were convicts transported from English jails. But most immigrants by far sought economic opportunity. Many could not afford the passage to the colonies and came as indentured servants. Such a servant signed an indenture (contract) to work for four to seven years to repay the cost of the ticket. Black people from West Africa came to the colonies involuntarily. Some of the first Africans were brought as indentured servants, but most Africans arrived as slaves.

By 1700, there were about 250,000 people living in the American Colonies. Approximately 450,000 immigrants arrived between 1700 and the start of the American Revolution (1775–1783). During that period, there were fewer English immigrants, while the number from Germany, Ireland, and Scotland rose sharply. Most immigrants arrived in Philadelphia, the main port in the colonies.

Wars in Europe and the United States slowed immigration during the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Newcomers included Irish fleeing English rule and French escaping revolution. The U.S. Congress made it illegal to import slaves as of 1808. By that time, about 645,000 Black Africans already had been imported as enslaved workers.

By 1820, New York City began to replace Philadelphia as the nation’s chief port of entry for immigrants. The first U.S. immigration station, Castle Garden, opened in New York City in 1855. Ellis Island, the most famous station, operated in New York Harbor from 1892 to 1954.

The second wave.

In the mid-1800’s, some states and railroad companies sent agents to Europe to attract settlers. Better conditions on ships, as well as steep declines in travel time and fares, made the voyage across the Atlantic Ocean easier and more affordable. Gold was discovered in California, and Chinese immigrants and sojourners streamed across the Pacific Ocean to strike it rich. Sojourners were temporary immigrants who intended to make money and return home. French-Canadian immigrants opened still another path to the United States. They moved across the Canadian-U.S. border into the New England States and Michigan.

The flood of immigrants began to alarm many native U.S. citizens. Some feared job competition from foreigners. Others disliked the newcomers’ politics, or the fact that many were Roman Catholics. In the 1850’s, the American Party, also called the Know-Nothing Party, tried to restrict the immigration of Catholics. American Party candidates were elected mayors of major cities, including Boston and Chicago, and barred immigrants from city jobs. Although the party soon died out, it reflected the concerns of some Americans.

During the 1870’s, the U.S. economy suffered a depression while the economies of Germany and the United Kingdom improved. German and British immigration to the United States decreased. But arrivals increased from Canada, China, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and southern and eastern Europe. In 1875, the United States passed its first restrictive immigration law. It prevented convicts and prostitutes from entering the country.

During the late 1870’s, California labor leader Denis Kearney and his Workingmen’s Party demanded a stop to Chinese immigration. Mobs sometimes attacked Chinese immigrants, who were accused of lowering wages and of unfair business competition. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the United States.

The third wave.

From 1881 to 1920, more than 23 million immigrants poured into the United States from all over the world. Through the 1880’s, most newcomers were from northern and western Europe. They later became known as old immigrants. Beginning in the 1890’s, the majority of arrivals were from southern and eastern Europe. They were called new immigrants. Many U.S. citizens believed the flood of immigrants threatened national unity. Hostility turned against Catholics, Jews, Japanese, and the new immigrants in general.

After the Chinese Exclusion Act, U.S. legislation passed in 1882, 1903, and 1907 expanded the list of banned immigrants to include professional beggars, contract laborers, insane persons, unaccompanied children, and numerous others considered undesirable. In 1907, Congress formed the U.S. Immigration Commission to study the origins and results of immigration to the United States. It generally was known as the Dillingham Commission, after its chair, Senator William Paul Dillingham of Vermont. In 1911, the commission issued a report in which it concluded that immigrants from southern and eastern Europe had more “inborn socially inadequate qualities than northwestern Europeans.”

In 1917, Congress enacted a law requiring new immigrants 16 years of age and older to show they could read and write in at least one language. The law also banned immigrants from the Asiatic Barred Zone, an area covering most of Asia and most Pacific islands.

In 1921, new laws reduced immigration and limited the number of immigrants from any one country. The Immigration Act of 1924 limited the number of immigrants from outside the Western Hemisphere to about 153,700 a year. The act limited the number of immigrants from different countries based on percentages of the nationalities making up the United States’ white population in 1890 and 1920. This formula severely hindered immigration from southern and eastern Europe.

In 1924, the United States also established the Border Patrol to prevent unlawful entry along U.S. boundaries. However, the problem of illegal immigration remains. Experts estimate that millions of people live in the United States illegally. A majority of illegal immigrants in the United States are from Mexico.

A temporary decline.

During the Great Depression of the 1930’s, U.S. policymakers continued to restrict immigration. As a result, many Jews fleeing persecution in Europe did not find a safe haven in the United States. Only about 500,000 immigrants arrived in the country from 1931 to 1940.

World War II (1939-1945) led to an easing of immigration laws. The War Brides Act of 1945 admitted the spouses and children of U.S. military personnel who had married while abroad. China became an ally during the war, so the ban against Chinese immigrants was lifted.

In 1952, the Immigration and Nationality Act, also called the McCarran-Walter Act, established quotas (allowable numbers) for immigrants from Asian countries and other areas from which immigrants had not been accepted. The law made U.S. citizenship available to people of all origins for the first time.

The fourth wave.

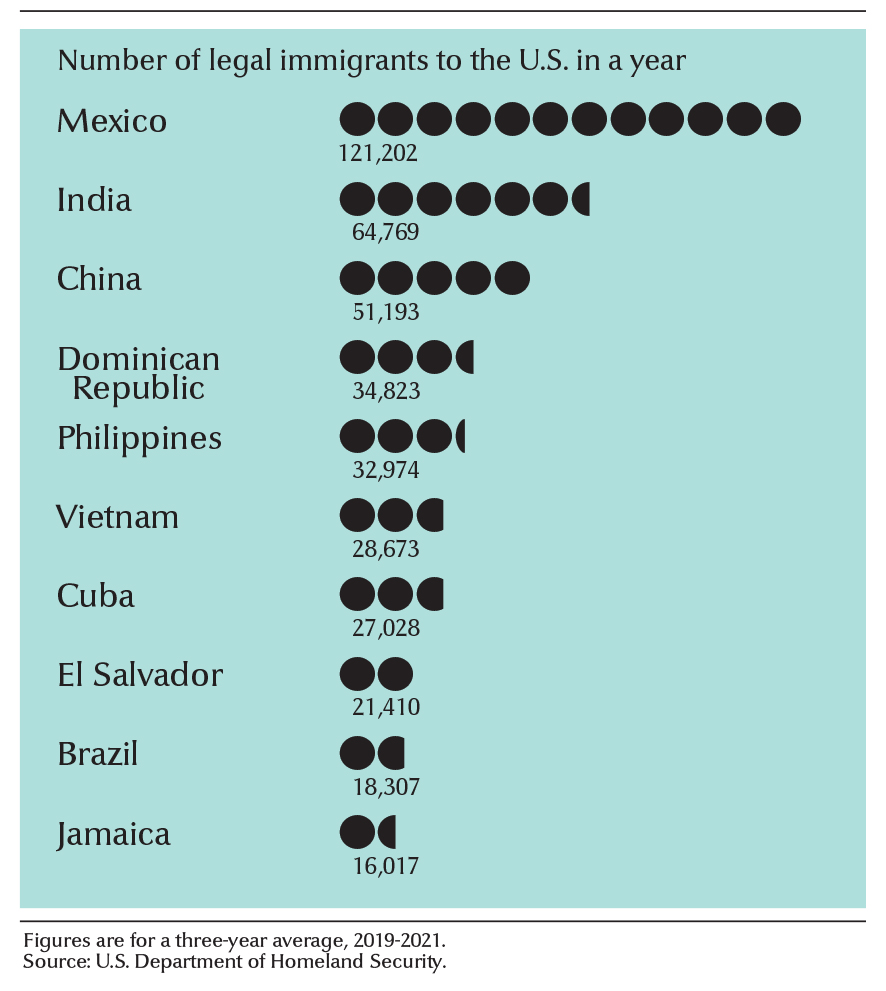

In 1965, amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act ended quotas based on nationality. Instead, the amendments provided for annual quotas of 170,000 immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere and 120,000 from the Western Hemisphere. The act established a preference system for issuing visas (entrance permits) that favored mainly relatives of U.S. citizens and of permanent resident aliens. The system also allowed for the immigration of people with special skills. Wives, husbands, parents, and minor children of U.S. citizens could enter without being counted as part of the quota. In 1978, Congress replaced the separate quotas for the Eastern and Western hemispheres with a single annual world quota of 290,000.

The 1965 amendments produced major changes in immigration patterns. The percentage of immigrants from Europe and Canada dropped, and that of immigrants from Asia and the Caribbean region soared.

Under the 1965 amendments, refugees could make up 6 percent of the Eastern Hemisphere’s annual quota for immigration. This rule was later extended to the Western Hemisphere. But the percentage was too small to accommodate the flow of refugees from war-torn Southeast Asia in the 1970’s and the Cubans and Haitians emigrating because of poor economic conditions and political repression. To address these issues, Congress passed the Refugee Act in 1980. This law provided for the settling of 50,000 refugees each year. The president could admit additional refugees if there were compelling reasons to do so. As a result, about 100,000 refugees entered the United States annually in the 1990’s.

The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 offered amnesty (pardon) to illegal immigrants who had lived in the United States continuously since before Jan. 1, 1982, or had worked at least 90 days as farm laborers there between May 1, 1985, and May 1, 1986. The act also set penalties for employers who knowingly hire immigrants without legal status. By the end of the amnesty application period in 1988, almost 3 million people had applied. But hundreds of thousands more did not apply for various reasons, including the cost and confusion involved in applying and a lack of residency or employment records.

In the first decade of the 2000’s, some states and cities enacted laws to deal with illegal immigration. However, federal courts blocked such measures. They ruled that regulating immigration was a federal responsibility.

In 2012, the federal government launched the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program to protect illegal immigrants brought to the United States as children. The program provided them with work authorization and shielded them from deportation.

Immigration to other countries

The most commonly traveled immigration route historically has led from Europe to the United States. But other countries also have received many immigrants. This section discusses immigration to other parts of the world.

Canada.

The French and later the British colonized Canada. From 1850 to 1930, more than 6 million people immigrated to Canada, including 3 million from the United Kingdom and the United States. In the late 1800’s, Chinese workers were imported to help build the Canadian Pacific Railway. To discourage Chinese immigration after completion of the railway in 1885, Canada placed increasingly heavy entry taxes on newly arrived Chinese. In 1923, Canada barred the entry of Chinese immigrants.

Today, Canada admits immigrants regardless of their ancestry, race, religion, or sex. Canada has one of the world’s highest immigration rates compared with population. Since the mid-1980’s, about half of Canada’s immigrants have been Asians, including Chinese, who once were barred.

Canada uses a point system that gives priority to immigrants who have education and skills that are likely to make them successful in Canada. To receive an immigrant visa, applicants must obtain a minimum number of points set by the government. They receive points based on such factors as their level of education, work experience, and ability to use English and French, Canada’s official languages. The point system does not apply to refugees and asylum seekers.

Latin America.

Most Latin American countries gained independence from their European rulers in the early 1800’s. At that time, only Argentina, Brazil, and a few other countries welcomed immigrants. From 1850 to 1930, more than 11 million people immigrated to Latin America. About 5 1/2 million of them—mainly Italians and Spaniards—went to Argentina. About 4 million—mainly Italians and Portuguese—went to Brazil. But many of the immigrants did not stay in their new countries.

After the 1950’s, immigration to Latin America declined because of the region’s lack of jobs and its rapidly growing population. In addition, Argentina and Brazil limited Asian immigration. However, much immigration took place within Latin America.

In the 1980’s, large numbers of people emigrated from Central America to the United States. Many were fleeing civil wars but were not accepted as refugees. As a result, they entered the United States illegally.

Today, more people emigrate from Latin America than immigrate to the region. Mexico is Latin America’s chief country of emigration. Most Mexican emigrants go to the United States. Many people born in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica also have emigrated from Latin America, usually to the United States.

Australia and New Zealand

were colonized by the United Kingdom beginning in the late 1700’s. After gold was discovered in Australia in 1851 and in New Zealand in 1861, non-British immigrants began to arrive. By the 1880’s, the immigrants included more than 40,000 Chinese in Australia and more than 4,000 in New Zealand. Both countries then limited Chinese immigration. In the early 1900’s, they established policies to preserve a “white Australia” and a “white New Zealand.” They tried to attract British and other favored immigrants by offering free transportation.

After World War II ended in 1945, Australia started to welcome European refugees. In 1975, the country began admitting Southeast Asian refugees. New Zealand eased its immigration restrictions in 1986.

In the late 1900’s, both Australia and New Zealand adopted point systems to select immigrants. The number of Asian immigrants rose as Chinese, Indian, and other Asian students arrived to study in Australia and New Zealand and stayed to live and work. A growing share of immigrants to Australia and New Zealand are from the Pacific Islands. In addition, many British subjects still migrate to Australia and New Zealand.

Asia.

Except in Israel, most immigrants living in Asia have moved from one Asian country to another. By the 1920’s, more than 8 million Chinese lived outside China, chiefly in the Philippines, present-day Indonesia, and other Southeast Asian lands. The Communist take-over of China in 1949 led 2 million more Chinese to emigrate.

About 750,000 Japanese lived in China, Korea, and other countries of eastern Asia by the 1920’s. Also by the 1920’s, about 1 1/2 million Indians lived outside their homeland. Many lived in other Asian countries, including what are now Sri Lanka and Malaysia. In 1947, Pakistan was created from parts of India. About 10 million people fled from one country to another. Hindus and Sikhs fled from Pakistan to India. Muslims left India for Pakistan. After East Pakistan became Bangladesh in 1971, millions more Hindus and Sikhs went to India.

By the late 1980’s, almost 2 million refugees had fled countries of Southeast Asia because of warfare. Many of them settled in the United States. But large groups remained in Malaysia and Thailand and the other Southeast Asian lands to which they had first fled.

European Jews began to settle in what is now Israel in the mid-1800’s. In 1914, about 85,000 Jews lived in the region. By 1948, when Israel was founded, some 450,000 more Jews had arrived, most of them from central and eastern Europe. In 1950, Israel passed the Law of Return, which allows almost any Jew to settle in Israel. Since the founding of Israel, about 3 1/3 million people have immigrated there. In the late 1980’s and 1990’s, hundreds of thousands of Jews emigrated from the Soviet Union and former Soviet lands.

Africa.

Colonial rule ended in most of Africa by the 1960’s. Since then, civil wars in African nations have driven millions of people from their native countries as refugees. Many others have emigrated because of famine. Most of the refugees have remained in Africa. Today, many African refugees live in Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, and Uganda. During the 1980’s and 1990’s, many Ethiopian Jews immigrated to Israel.

Vast numbers of people also move about on the African continent in search of better farmland or employment opportunities. Many go to Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa.

Europe.

In the first half of the 1900’s, the Russian Revolution and two world wars caused huge population shifts within Europe as refugees fled from one country to another. Economic recovery after World War II generated a great need for labor. Many countries, including Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and West Germany, sought foreigners to serve as guest workers. Most such temporary workers came from southern Europe and northern Africa. In the late 1970’s, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain drew workers from Africa and Asia.

Many guest workers settled in their host countries with their families. Additionally, some countries, including France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and the United Kingdom, received millions of immigrants from their former colonies. Europe’s non-European population grew hugely. Guest worker recruitment ended in the early 1970’s. European countries also began to set stricter requirements for immigration from former colonies.

In the 1990’s and early 2000’s, millions of immigrants arrived in Western Europe seeking better economic opportunities and political freedoms. They came largely from Eastern Europe, northern Africa, southern Asia, and the Middle East. The fall of Communism in Europe and the enlargement of the European Union during the early 1990’s enabled many Eastern Europeans to move west in search of higher wages. Many Muslims also immigrated to the region, and cultural tensions sometimes arose.

In the 2010’s, the number of refugees immigrating to Europe increased sharply as people fled conflict and terrorism in northern Africa and the Middle East, including Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. The receiving countries often found their resources strained, and right-wing political parties attracted new support by opposing immigration.