Industry is a group of businesses that produce a similar product or provide a similar service. For example, companies in the automobile industry manufacture cars and trucks. Companies in the banking industry make loans, handle investments, and provide other financial services.

There are thousands of industries. They include home construction, advertising, film production, farming, meat packing, mining, and electronics manufacturing.

Many industries change a raw material into a useful product. For example, the steel industry makes steel from iron ore mined from the ground. Some industries, such as railroads and trucking, move goods from place to place. Other industries provide such services as electric power, health care, and education.

The term industry can also be used to mean all the businesses—considered as a whole. In this sense, industry provides people in many countries with almost all their clothing, food, shelter, and other basic needs. Industry also provides much of our entertainment, labor-saving appliances, medicines, and many other comforts.

Although industry enriches the quality of life, it can create harmful side effects. For example, factories may pollute the air, water, and soil and endanger people’s health. Businesses may also take advantage of consumers. For example, a bank may make expensive, risky loans to people who do not fully understand the terms.

This article describes how industries are classified and what industry needs for production. It also discusses how businesses compete within industries, how governments regulate industry, and how industry varies around the world. To learn about the history of industry, see the articles Industrial Revolution and Invention . To learn more about how individual businesses operate, see Business . For information on particular industries, see the list of Related articles at the end of this article.

Classification of industries

In an attempt to organize the vast amount of information about industry, economists have developed various classification systems. Each system groups industries that are similar in some important way, such as what stage of production the industry belongs to, how its products are used, or how stable the industry is.

By stage of production.

One method classifies industries into stages of production. Industries such as agriculture, fishing, and mining belong to the first stage of production. In this stage, natural resources or raw materials are obtained. These industries are called primary industries or extractive industries.

The chemical, textile, and other manufacturing industries make up the second stage of production. In this stage, raw materials are turned into finished goods. Such industries are called secondary industries or fabricating industries.

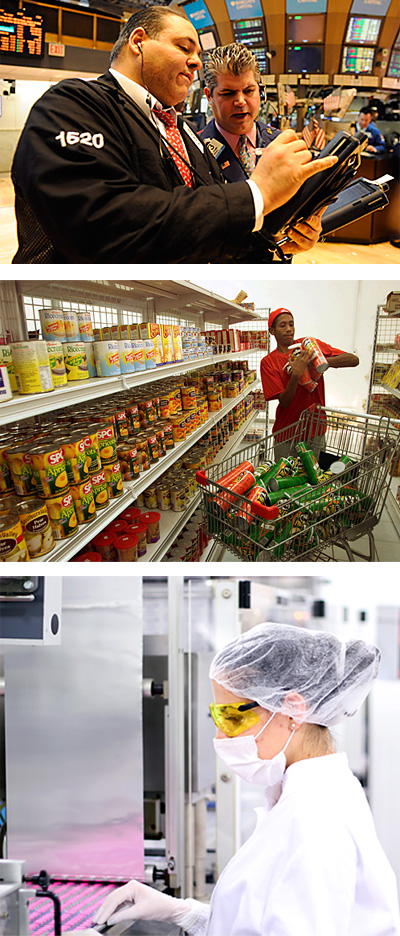

The third stage involves the movement of goods from producers to consumers. Industries at this stage of production include automobile dealers, drugstores, and trucking firms. They are known as tertiary industries or distributive industries.

By the way goods are used.

To study price competition or the effectiveness of advertising, economists may group together products that are close substitutes for one another. For example, tin cans and glass jars serve many of the same purposes. But because they are made from different materials, they fall into different major industry groups under other systems of classification.

For some studies, economists divide industries broadly between producers of durable goods and producers of nondurable goods. Durable goods are products designed to last a long time, such as appliances and furniture. Nondurable goods consist of products that are used up or wear out quickly, such as food and clothing. During periods of economic decline, durable goods industries suffer more than do nondurable goods industries. People can postpone buying new furniture, for example, but they must purchase food.

Industries can also be divided into those that make consumer goods and those that make producer goods. Consumer goods are purchased by individuals. They include household clothing, electronic games, and other items for personal use. Producer goods, also called capital goods, are purchased by businesses. They include tractors and machinery as well as steel and various chemicals used to make other products.

The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS)

is used by the governments of Canada, Mexico, and the United States for classifying industries. The NAICS classifies businesses into 20 major sectors. Each sector is represented by one or more two-digit numbers. The numbers and their sectors are listed in the table Sectors of industry in this article. Each of the 20 sectors is further divided into specialized industry groups. These groups may be divided into more and more specialized groups. The groups are represented by three-, four-, five-, and six-digit codes.

The needs of industry

Experts who study industry use the term output for any item, material, or service that an industry produces. An output could be a length of fabric, a refrigerator, or legal advice. To produce an output, a business uses inputs, also called productive resources. The amount and quality of the output depend in part on the amount and quality of the inputs. The output also depends on how well a producer uses inputs.

Industry requires five basic inputs for production: (1) natural resources, (2) capital, (3) technology, (4) labor, and (5) management. Some experts group technology and capital together. Likewise, management is sometimes grouped together with labor.

Natural resources

include lumber, mineral deposits, soil, sun, water, and living things. Natural resources are especially vital to agriculture, fishing, mining, and certain other industries. On the other hand, service industries—such as banking and insurance—require relatively few of Earth’s resources. Some industries can substitute plastics and other synthetics for natural materials. But such synthetic materials are made by other industries from natural resources, such as oil.

The supply of certain natural resources is limited. These resources are called nonrenewable. For example, Earth has limited deposits of coal, natural gas, and oil. Once used, they cannot be replaced. Other resources, such as forests, are renewable. People can plant new trees to replace the ones used by industry.

Capital

has two meanings in industry. It refers to the money that a firm needs to hire workers, to buy supplies, and to pay bills. This money is called working capital. Capital also means capital goods—that is, buildings, machinery, tools, and other items that industries use to provide products or services for consumers.

Working capital

may come from a business’s profits. Profits are the money a business makes selling its products, subtracting the money it takes to produce them. New businesses, however, may not yet make profits. In addition, expanding businesses may require more capital than they can get from profits alone. Such businesses can raise capital by borrowing money from a bank. The business must pay back such a loan with interest. A business can also raise capital by selling bonds to investors. The business promises to pay back the amount of the bond, plus interest, to the investor at a later date.

Another way of raising capital involves selling stock in the business. The people who buy stocks are called stockholders. A business is not obligated to repay the money to stockholders. Instead, stockholders become additional owners of the business. Their ownership is represented by the shares of stock that they own. Although stockholders receive no repayments or interest from the business, they often receive dividends from the business. Dividends are a share of the business’s profits. They are paid according to the number of shares owned by a stockholder. The more profitable a business becomes, the more money stockholders get in return. from the business. Dividends are a share of the business’s profits. They are paid according to the number of shares owned by a stockholder. The more profitable a business becomes, the more money stockholders get in return.

Capital goods

include such durable goods as a bakery’s ovens, as well as the flour, sugar, and other ingredients used in a bakery’s products. When a business acquires more capital goods, it increases the amount of products or services it can make. Purchasing capital goods is called investment. Investment can be expensive. But industries that invest wisely can eventually make much more profit.

Some industries require a large investment in capital goods. Such capital-intensive industries include the electric power and petroleum industries. These industries rely on complex, expensive machinery to make their products. They also rely on infrastructure—that is, services and facilities such as pipelines and power lines—to deliver their products to consumers (see Infrastructure ).

Technology

refers to all types of machines, materials, and tools. It also refers to the techniques and knowledge needed to create, maintain, and use these devices. Technological inputs available to industry may differ greatly from country to country. Developing better technology—much like capital investment—can be difficult and expensive. But it can pay off in the form of increased production and future profits. For a detailed discussion of this aspect of industry, see the article Technology .

Labor

is the work that people do to produce goods and services. All industries require labor. However, some industries require far more money for labor than for other inputs, such as machines or materials. Such labor-intensive industries include accounting, law, and most other service industries.

The amount of labor available to industry depends on several factors. These factors include the size of the population, the proportion of the population working or seeking work, and the hours each person works.

Labor varies in quality. People differ in their inherited abilities and acquired skills. Education and training can increase a worker’s skills. But education and training require a present sacrifice of money and time for an expected future benefit. In this sense, education and training are similar to investment in capital goods. Thus, the skills of the labor force are often referred to as human capital. The total output divided by the total amount of labor used is called the rate of labor productivity.

Management

is a special kind of labor that involves making business decisions. Managers decide such matters as what to produce, which markets to serve, how much to advertise, and what prices to charge. They also employ or direct the other inputs.

The maximization of profits is the fundamental goal of businesses. Managers must balance a number of factors to ensure high profits. Managers usually aim to keep the costs of production as low as possible. But if managers rely on cheap, low-quality inputs, the quality of the business’s products and services may suffer. Ideally, managers try to sell products and services at high prices. But if such products and services are too expensive, customers will buy cheaper ones from other businesses instead. Management must balance a number of factors when making these decisions.

Input mix.

An important decision managers make is their choice of input mix—that is, what combination of capital, labor, and raw materials to use in production. If labor costs are high, for example, a business may invest in automatic machinery so that it needs fewer workers. If labor is cheap, the company may employ extra workers instead of buying machines to do the job. An ideal combination of inputs will enable a business to produce its goods or services at the lowest possible cost, without reducing quality. This combination is called the most productive, or optimum, input mix.

Production location.

The goal of keeping production costs low also affects a company’s choice of location. The resources an industry needs and the customers it serves are rarely close to each other. As a result, a business must transport inputs, outputs, or both. Managers must try to keep transportation costs as low as possible.

Transportation costs are based on the weight and bulk of materials being transported, as well as on distance. A company’s ideal location may thus depend on whether the company’s product is heavier or lighter than the materials used to make it. The soft drink industry, for example, produces weight-gaining products. Soft drinks are mostly water. They contain a tiny amount of syrups and flavoring bases, which are light and cheap to transport. After adding water, the products become much heavier and more expensive to transport. Soft drink companies thus maintain a number of bottling factories serving local customers, rather than distributing soft drinks from one central location.

The paper and wood pulp industries, on the other hand, are examples of industries that produce weight-losing products. The inputs—large tree trunks—are much heavier than the outputs that must be transported to consumers. Many such industries are near forests, which are the sources of their raw materials.

Expansion.

A successful business makes large profits with which to invest and expand production. But the act of expansion itself can also lead to increased profits.

Many businesses benefit from economies of scale. That is, they can make and sell goods more cheaply when they produce large quantities. Economies of scale are common in capital-intensive industries, such as manufacturing. For example, if an automobile factory only made a single car, that car would be extremely expensive. The car’s price would need to cover not just the materials and labor used to make the car, but also the entire cost of building the factory. But if the factory makes thousands of cars, each car’s price needs to cover only a small fraction of the factory’s cost. Economies of scale also exist in certain service industries, such as education. Educating many students at a university is cheaper, per person, than educating only a few. Other industries—such as gourmet restaurants and landscaping—do not benefit as readily from economies of scale.

Industrial organization

A specialized field of economics called industrial organization concerns itself with how businesses within an industry compete and make decisions. A fundamental question that industrial organization economists study is how businesses can make sufficient profits in the face of competition.

Consumers typically favor low prices, so competition can force a business to lower its price below the level necessary to earn a profit. If the business cannot lower its production costs to accommodate the lower price, it may fail. It is ideal for consumers if competition weeds out businesses that cannot offer quality products or services at low prices. But in some industries, competition does not drive down prices much. Industrial organization economists try to understand what factors prevent competition from driving down prices. Such factors vary from industry to industry.

Industrial organization economists also study how businesses make decisions in response to the actions of their competitors. They often use a branch of mathematics called game theory to describe and analyze the behavior of businesses. In game theory, business decisions are modeled as back-and-forth actions among players in a relatively simple game. Using game theory, economists can understand the abstract patterns that underlie competition among businesses.

Product differentiation.

Certain industries produce commodities, goods that are nearly identical to one another. For example, cotton produced by one farm is much the same as cotton produced on another farm. Cotton buyers thus do not place a higher or lower value on cotton produced by any particular farm.

In contrast, other industries are characterized by product differentiation. When businesses successfully differentiate (distinguish) their products from those of competitors, the products can generally be sold at higher prices. For example, designer jeans are differentiated products. Different pairs of jeans, although serving the same function, may have different styles. Consumers place a high value on a particular style and brand of designer jeans. Thus, competition among brands does not typically drive down the price of designer jeans.

In an industry characterized by differentiated products, businesses can typically sell their products for much more than the cost of inputs, earning high profits. Industries that produce commodity goods, on the other hand, must struggle to control the cost of inputs to stay competitive. Marketing plays an important role in differentiating products. Successful marketing campaigns can convince customers that such products have a value much higher than their input costs.

The location of a business can be viewed as a form of product differentiation. For example, dry cleaners everywhere provide similar services. But consumers typically will not go to a faraway dry cleaner to get a deal better than that offered by their local dry cleaner. Thus, competition between distant dry cleaners does not drive down the price of their services.

Search and switching costs

hinder price competition in certain industries. Search cost refers to the time or effort a consumer must spend researching and comparing the value of competing products. Specialized, technical services often have high search costs. For example, it can be difficult and time-consuming to compare the skills and reputations of competing doctors. Thus, patients often return to doctors they have already used, even if a better doctor might be nearby.

Switching cost refers to a consumer’s difficulty in switching between competing products. For example, mobile phone companies often charge consumers a fee if they switch to a competitor’s phone service before a certain time. This fee is a switching cost. But a switching cost can also take the form of effort, rather than money. For example, Apple Inc. and Microsoft Corporation make competing types of software for personal computers. The two types of software work slightly differently. Consumers who are used to one type of software often have trouble adjusting to the other. Thus, such consumers may be reluctant to switch to the competitor’s software, even if it works better for their purposes.

Both search costs and switching costs tend to keep consumers from switching to a business’s competitors. Competing businesses have more difficulty drawing such customers away. Thus, competition may not lower prices much in industries characterized by search and switching costs.

Network effects,

also called network externalities, can also hinder competition. A network effect refers to the fact that certain products become more valuable as more people use them. The telecommunications industry, for example, benefits from a network effect. A telephone increases in value as more people get telephones, because each telephone owner can call more people. Similarly, a social networking website increases in value as more people use the website. However, other products—such as pencils and tea—are not characterized by network effects.

Collusion

occurs when businesses do not compete but instead agree to limit or stop competition with one another to keep prices artificially high. In the 1800’s, for example, United States shipping companies agreed to raise their prices in unison. Shipping customers thus had to pay much higher prices than they would in a competitive market.

Today, most developed countries have laws against collusion. Nevertheless, businesses may collude in secret. Industrial organization economists are sometimes asked to help detect and prevent collusion.

Government regulation

In developed countries, nearly all industries are subject to some degree of government regulation. Such regulations aim to limit or prevent problems associated with business activity that can harm the public good. Certain industries are regulated more than others. For example, the nuclear power industry and the pharmaceutical (medicinal drug) industry are highly regulated.

Many regulations are designed to protect consumers and workers. But enforcing regulations is often costly. Eventually, consumers typically bear these costs. Companies may charge consumers more money, for example, to make up the cost of complying with regulations. Consumers also have to pay taxes to fund government regulatory agencies.

Social costs,

especially those created by negative externalities, are an important reason for government regulation. A negative externality is a cost associated with industrial activity that is not included in the price consumers pay. Environmental pollution is an example of such a cost. The costs of pollution include damage to soil, air, and water quality as well as medical treatment for people harmed by pollution. These costs are outside those included in the price of industry’s products. Overfishing is another industrial activity that creates a negative externality—namely, a dwindling supply of fish.

Much government regulation seeks to prevent or minimize social costs. In the United States, for example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issues regulations for factory and automobile exhaust and groundwater contamination. It also regulates industrial activity that harms endangered species. Many other countries have similar regulations. Many governments regulate the fishing industry by forcing companies to limit the amount of certain fish they catch. The cost of complying with such regulations can be substantial to industry.

Lack of information

is another problem that governments regulate. If consumers lack important information about goods or services, a seller might take advantage of their lack of knowledge. Economists use the term information asymmetry for the condition in which one party has more or better information than the other. For example, a business that does not list the ingredients in a food product may be able to trick consumers into paying a higher price than they otherwise would. In the case of medicine, active ingredients may harm consumers who do not know about them.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires the food industry to list nutrition facts and ingredients on food labels. It also requires the pharmaceutical industry to prove that the drugs it sells are safe and effective. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is another U.S. regulatory agency. It requires businesses to report vital information about their performance to stockholders. The governments of other developed countries have similar regulations and agencies. It can take an industry much time and money to comply with such regulations, such as proving the safety of a new drug.

Monopolies

—another concern for government regulation—form when competition ceases to exist. For example, one business may come to dominate an entire industry. Or, it may be the only business offering certain services in a particular region, such as a grocery store in an isolated area. Lacking competitors, such a business can charge high prices. It can also sell low quality products without fear of losing sales to competitors.

In many industries, government regulation seeks to prevent monopolies from forming. In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has the power to prevent businesses from merging together if such mergers would lead to a monopoly.

In other industries, the government allows monopolies to exist but strictly regulates them. For example, many electric power and gas companies are regulated monopolies in their areas. Such companies, called public utilities, might control all of an area’s supporting facilities. The government typically forces such companies to offer consumers reasonable prices. But the companies have little incentive to improve quality or innovate because they are protected from competition.

Industry in developing countries

Industry differs greatly between wealthy and poor countries. Wealthy or developed countries include most nations in Europe and North America, as well as Japan. Many poorer nations are developing countries that are in the process of shifting from an economy based on agriculture to one based on industrial production. They include most countries in Asia and Latin America. Some economists prefer the term less developed countries for the poorest nations, such as some of the countries in Africa.

Industry in developed countries produces more goods and services per person than it does in developing ones. The low production in developing nations may result from shortages of machinery and other capital goods. It may also stem from a lack of advanced technology. Workers are less productive if they do not use the latest machines and production techniques. Developing nations may also lack sufficient human capital, including the engineers, managers, and skilled workers needed for industrial growth.

Developing nations also differ from developed countries in what they produce. Much of the industry in developing countries provides food and other basic needs. In developed countries, service industries play a more dominant role. In addition, many developing nations produce only one or two raw materials, which they exchange with the rest of the world. They suffer if the price of these materials falls. See Developing country .

Development economists study the factors that may restrict economic growth and industrial expansion in developing and less developed countries. Some hindrances include corruption, weak legal systems, and overly complicated rules for setting up and operating businesses. In addition, many industries are interdependent, meaning they cannot exist in the absence of other, related industries. For example, auto manufacturers need the steel and plastic industries. Software programmers need the computer chip industry. Thus, industries face difficulty expanding into developing countries that lack established related industries.