Ireland, History of. The history of Ireland is the story of a small island nation west of the island of Great Britain and the mainland of Europe. The country’s location greatly influenced its history and growth. Ireland received most of its early settlers from the mainland of Europe. Over thousands of years, trade and migration brought new technologies, language, and religious practices to the island. Combining new ideas with long-held traditions, the island’s people came to create a uniquely Irish culture and way of life.

From the 1160’s through the 1900’s, the relationship between England and Ireland formed the central theme of Irish history. The English attempted to conquer Ireland, but the Irish put up a strong resistance. Ireland suffered through devastating wars that impoverished it. English and Scottish landlords took over most of Ireland’s land. Political and religious tensions and economic problems forced many Irish people to emigrate to other countries. As a result of these challenges, Ireland became divided. Twenty-six counties, from Donegal on the northwest coast to Cork in the south, make up the independent Republic of Ireland. Six northeastern counties make up Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Ancient Ireland (Prehistoric times to A.D. 400’s)

Early peoples.

People have lived in what is now Ireland for thousands of years. However, there is little evidence that people inhabited Ireland before about 12,500 years ago. About 10,000 or 9,000 years ago (8000 or 7000 B.C.), people from the European mainland settled in Ireland. Early settlers were seafarers, and their settlements were generally along the coast. Later inland settlements were usually close to lakes and rivers. Evidence of early settlements has been found near what is now Larne in Northern Ireland, at Limerick in southwestern Ireland, and at Offaly in the central lowlands. The early peoples of Ireland lived by hunting and fishing, and their tools included knives and scrapers made of flint. Tools from the earliest eras of Irish settlement have been discovered at various places in Ireland. Important archaeological discoveries have been made at Dalkey Island, south of Dublin; around Lough (Lake) Neagh, in the northeast; and in the River Bann valley, in the north.

About 4500 B.C., another wave of settlers arrived. They used domesticated (tamed) animals and grew grain. The settlers made textiles, pottery, and tools of polished stone. They lived in small communities in round or rectangular wooden houses with straw roofs. The most striking discoveries from this period are the megaliths (great stone monuments) that the settlers erected as communal graves and for religious and ceremonial purposes. The simplest type of megalith is the dolmen, which consists of three or more upright stones, with a flat capstone laid across them. Most dolmens were probably covered in earth to form a barrow, or burial mound. An impressive example of the dolmen stands at Legananny, in County Down, Northern Ireland. The most striking megaliths are burial chambers called passage graves, such as the one in Newgrange, in County Meath.

As the Bronze Age spread from the Middle East about 2000 B.C., metalworkers in Ireland learned to make bronze, a mixture of copper and tin. At that time, Ireland had abundant resources of copper and gold, and the country became an important center of metalwork. Irish metalworkers exported metal goods to Britain (now the United Kingdom), France, Iberia (now Portugal and Spain), Crete, and other areas. These exported goods included torques (necklaces of twisted metal), bracelets, and other ornaments.

The Iron Age and Celtic culture.

The Celtic culture originated in the region between the Rhine and Danube rivers on the mainland of Europe. It began to flourish in Ireland around the 300’s B.C. Celtic languages, religion, and material culture—such as a knowledge of ironworking—spread to Britain and Ireland primarily by means of trade rather than migration. The Celtic language developed into what is now Gaelic, or Irish. See Celts.

Many of the people of Iron Age Ireland were farmers who grew cereal grains and flax, a fiber plant. They also tended large herds of cattle and sheep.

Scholars have learned only a little about the religious beliefs in Ireland after the arrival of Celtic culture. The people believed in a life after death, and in another world, sometimes called Tír na nÓg (Land of Youth). Their priests, who belonged to the learned class called Druids, offered sacrifices to the gods. Druids also included teachers, poets, and judges.

Ireland came to be divided into about 150 small communities called tuatha. A king ruled each tuath. Irish kings lived in houses fortified by banks of earth, or in lake dwellings called crannógs (see Lake dwelling). Sometimes a number of kings recognized one of their number as árd rí (high king) and paid tribute to him. In the same way, a number of high kings, or overkings, formed a kind of federation under the king of one of the country’s five provinces.

The original provinces, sometimes called the five fifths of Ireland, were probably Ulster, much of which is now Northern Ireland, and Leinster, Munster, Connacht, and Meath, in what is now the Republic of Ireland. But the number of provinces and their boundaries changed frequently. According to tradition, King Cormac mac Airt built a large palace at Tara, in Meath. He formed the new kingdom of Meath, and called himself high king.

The island of saints and scholars (400’s-700’s)

According to tradition, Saint Patrick brought Christianity to Ireland in the A.D. 400’s. But scholars now believe that other missionaries were first responsible for spreading Christianity there. As the new religion spread, monasteries sprang up throughout Ireland, and the island became a center of religious life and learning.

The coming of Christianity.

Patrick was born in Roman Britain and was taken to Ireland as an enslaved person in the early 400’s. After six years of slavery, he escaped to Britain. Patrick became obsessed with the idea of converting the Irish to Christianity. He went to France, where he studied for the priesthood. He returned to Ireland as a Christian missionary. According to tradition, Patrick landed at Saul, in Down, in 432, and built his first church there. For 30 years, he traveled the country, founding churches and admitting men to the priesthood. The Irish accepted Christianity and came to regard Patrick as their primary patron saint, the saint regarded as Ireland’s special guardian. Saint Patrick also helped popularize the Roman alphabet and Latin literature in Ireland. After his death, about 461, Irish monasteries flourished as centers of learning.

Modern scholars dispute the traditional accounts of Saint Patrick’s life and argue that a number of missionaries—including the British- or Roman-born Palladius—first introduced Christianity to the Irish. But all scholars agree that the people eventually accepted the new religion with little opposition. See Patrick, Saint.

Irish missionaries.

Saint Patrick and other missionaries divided the country into divisions called dioceses and put bishops in charge of them. In the years that followed, Christian missionaries founded many monasteries throughout the country. The chief founders of Irish monasteries were Saint Enda of the Aran Islands; Saint Finnian of Clonard; Saint Columba of Derry and Kells, who is also called Colmcille; Saint Brendan of Clonfert; Saint Brigid of Kildare; Saint Comgall of Bangor; Saint Finbarr of Cork; and Saint Ciaran of Clonmacnoise. Saints Brigid and Columba and Saint Patrick came to be considered the three patron saints of Ireland.

Gradually, monasteries became a major feature of Christian life in Ireland. The monasteries became so important that the system of dioceses founded by Saint Patrick broke down. Each monastery was independent, and the abbots (heads) of the monasteries eventually became more powerful than the bishops. See Monastery (History and development).

During the early Middle Ages, from about A.D. 500 to 800, religion and scholarship almost disappeared in some other countries. But Ireland became a great center of education and scholarship during this time. Many scholars from Britain and the mainland of Europe traveled to Ireland to study in its famous monastery schools. Scripture (study of sacred texts) and theology (study and description of God) were the chief subjects at these schools.

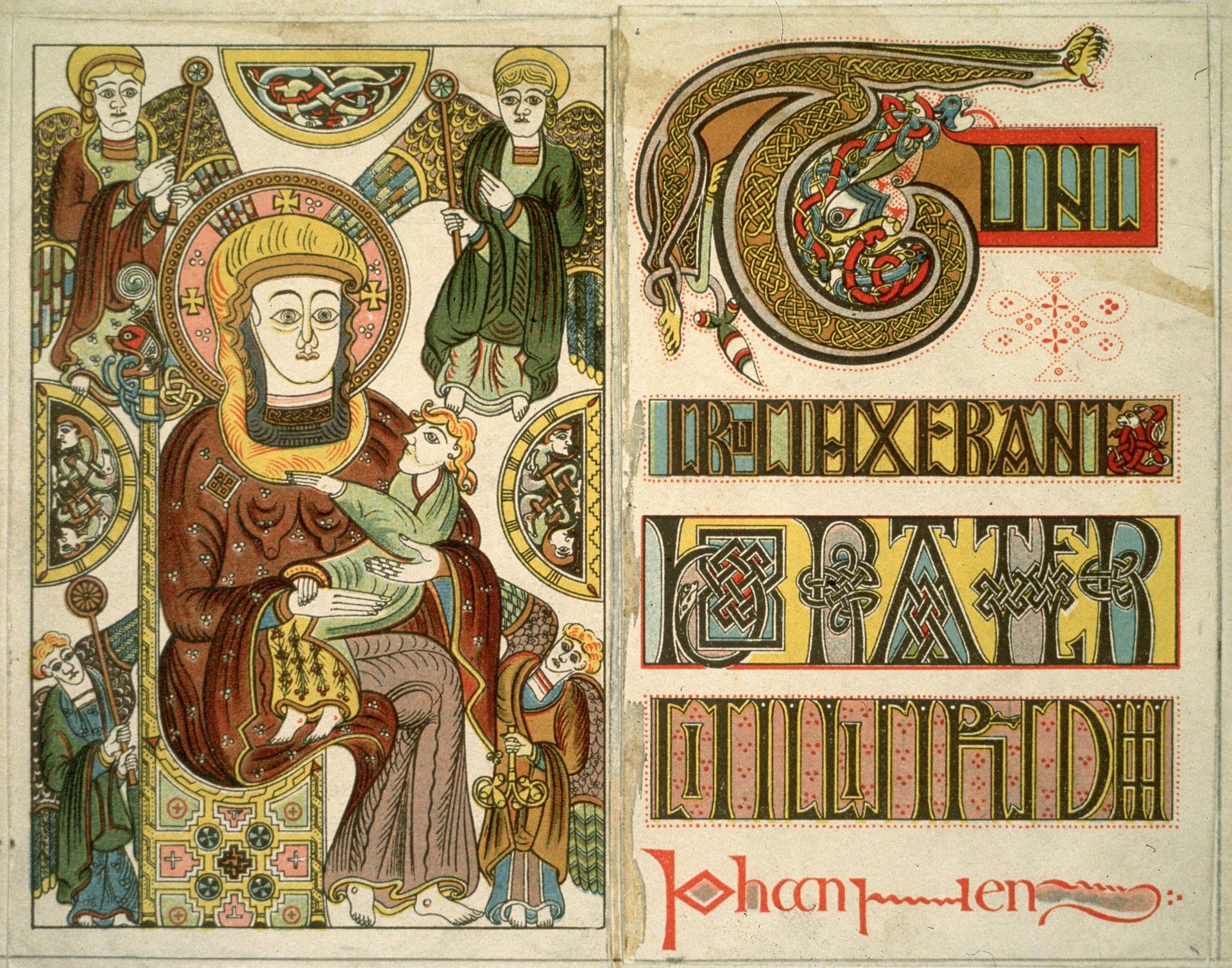

The monasteries contributed greatly to Irish art. Metalworkers created fine ornamental objects of this period, especially for the monasteries. Examples of such metalwork are the Ardagh Chalice, a bishop’s staff called the Innisfallen Crosier, and cumdachs (decorated boxes for storing sacred texts). The greatest artistic achievements of the period were illuminated manuscripts. Scribes created these hand-decorated manuscripts using bright colors and precious metals so they seemed to glow. Among the best known are the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow, and the Book of Armagh. The Cathach Psalter is the oldest of the surviving Irish illuminated manuscripts. See Book of Kells; Celtic art.

The Irish monks believed that the greatest sacrifice they could make was to go into exile and spread their beliefs. Saint Columba of Derry was one of the first missionaries to leave Ireland. In 563, he founded a monastery on Iona, a small island off the coast of Scotland (see Columba, Saint). From there, he and his successors taught the Christian religion throughout much of Scotland and northern England. They founded such monasteries as Lindisfarne. Other missionaries went to the mainland of Europe. They founded monasteries in many of the places that they visited, such as Bobbio, in what is now Italy, and Luxeuil, in France.

In time, the religious fervor of the monks declined. Some monasteries passed into the control of people outside the clergy who abused or abandoned the land and buildings. In the 700’s, a religious group called Céli Dé (servants of God) began a reform movement. They preached a return to the former strictness of monastic life. But before they gained much success, bands of warriors from Scandinavia called Vikings began to raid Ireland.

The Vikings in Ireland (700’s-900’s)

The first Viking raid occurred in 795, when Vikings plundered the monastery on Lambay Island, off the Dublin coast. At first, they came in small groups, made surprise attacks on places along the coast, and sailed away with their plunder (stolen goods). But after about 830, the Vikings changed their tactics. They sailed up the rivers to attack inland. Then they set up bases from which they attacked the surrounding countryside. They also began to stay in the country over the winter. In 841 and 842, they stayed over the winter at Dublin for the first time.

At first, the Irish were not successful in defending themselves against the invaders. Their weapons were inferior to those of the Vikings, and they had no permanent armies or fleets. The country also lacked political unity. The Irish kings quarreled among themselves, even during the worst periods of the Viking invasion. In the mid-800’s, however, the Irish began to put up a stronger resistance and to win victories over Viking forces. But they did not drive the Vikings out of the country, and a second wave of Viking attacks on Ireland began in 914.

By this time, the Vikings had established or expanded settlements at Wexford, Waterford, Cork, and Limerick, as well as at Dublin. These were among the first towns in Ireland, and the Vikings who lived in them began to develop trade. They also married into Irish families and eventually became Christians. Viking leaders became like other rulers in Ireland and joined in the wars between rival Irish kings.

Rival kings (900’s-1100’s)

The struggle for power among provincial kings went on despite the Viking invasions. By the end of the 900’s, Brian Boru, the king of a small state in the southwest called Dál Cais, had conquered his neighboring states. He became the strongest king in the southern half of Ireland. But Mael Morda, king of Leinster, began to plot against him. Mael Morda made an alliance with Sitric, the Viking king of Dublin, who got help from the Vikings of the Orkney Islands and the Isle of Man. Brian marched against them, and the two sides fought a great battle near Clontarf, north of Dublin, on Good Friday, 1014. It ended in victory for Brian’s army, but Vikings killed Brian in his tent. See Brian Boru.

For nearly 100 years after the death of Brian, rulers of powerful provincial kingdoms fought bitterly for supremacy. But none of them had any lasting success. In 1106, Turlough O’Connor became king of Connacht. He was a skillful warrior who strengthened his kingdom by erecting fortresses. He built bridges over the River Shannon, so that he could attack the other provinces swiftly, and he successfully used fleets of warships in naval battles. O’Connor tried to weaken his rivals by dividing their kingdoms. He divided Munster and Meath among a number of weaker kings. For a time, he was the most powerful king in Ireland.

O’Connor died in 1156. After his death, Murtagh MacLoughlin, king of the northeastern land of Ulster, made himself king of Ireland. Ten years later, MacLoughlin died, and Turlough’s son, Rory O’Connor, became the last native king of Ireland.

Religious and economic revival.

The period after the Viking invasion was a time of recovery for religion and the economy, despite the lack of stable political control. Church leaders reformed the Irish Church and reorganized it into dioceses. A church assembly called the Synod of Kells in 1152 divided the country into 36 dioceses, grouped into 4 provinces under the archbishops of Armagh, Dublin, Cashel, and Tuam. Saint Malachy of Armagh was the greatest of the religious reformers and introduced the Cistercian Order into Ireland. The Cistercians emphasize prayer, study, and manual labor. In 1142, the first Irish Cistercian monastery was founded at Mellifont in County Louth. See Cistercians.

In the 1000’s and 1100’s, the economy of Ireland was based on farming. A person’s wealth was determined by the number of cattle he or she owned. Irish society was organized, as it had been since ancient times, into communities called tuatha, based on family groups. The ruler of a tuath lived in a fortified house called a rath or dún, together with a brehon (lawyer), minstrel (musician), physician, and several craftworkers.

The Normans in Ireland (1100’s-1400’s)

The powerful Norman army, from the area in France now called Normandy, conquered England in 1066. In the 1160’s, Dermot MacMurrough, former king of Leinster, asked King Henry II of England for help in regaining his kingdom. Henry gave Dermot permission to recruit Norman soldiers in England. Most of the Norman knights who came to Ireland were from the Welsh Marches—that is, the lands along the border between Wales and England. MacMurrough promised the Normans a share of the land they helped him reconquer. Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, an English nobleman commonly called Strongbow, agreed to help. In return, MacMurrough promised to allow Strongbow to marry his daughter Aoife (also spelled Eva) and become king of Leinster.

Arrival of the Normans.

In 1169, a party of Normans led by Robert FitzStephen landed in Bannow Bay, on the southeast coast of Ireland, and began to seize territories. The Irish people were poorly armed and no match for the Normans. In 1170, Strongbow landed near Waterford with an army, captured the town, and married Aoife MacMurrough there. The first part of MacMurrough and Strongbow’s agreement had been kept. The second part soon followed. After the Normans captured Dublin, MacMurrough died suddenly. Strongbow then became king of Leinster.

Henry II was alarmed by these events. He had no intention of allowing any of his subjects to set up independent kingdoms in Ireland. In 1171, he crossed to Ireland to assert his authority over Strongbow. The Normans submitted to him at once, as did many Irish kings and nobles. The Irish may have believed that, if they recognized Henry as their overlord, he would protect their property. They were disappointed. Henry formally granted Strongbow control of Leinster, in return for Strongbow’s promise of loyalty and military service. Henry also gave a Norman soldier named Hugh de Lacy the kingdom of Meath.

After Henry returned to England, the Normans continued to seize the lands of Irish nobles. In the center of Ireland, the territories under the rule of Norman families stretched from Dublin across the central plain. The de Lacys held lands in Meath and Westmeath, and the de Burghs controlled large areas of Connacht. In the southwest, the Fitzgeralds held lands in Leinster and on the south bank of the River Shannon. The Butlers controlled territories in Munster. In the north, a Norman soldier named John de Courcy (also spelled Courci) seized the old kingdom of Ulster and ruled an area east of the River Bann, from Fair Head to Carlingford Lough.

Failure of the conquest.

By 1300, the Normans controlled most of the country. But they did not succeed in conquering Ireland as they had conquered England. Conquest was more difficult in Ireland because there was no central government that they could control. The Normans were not a united group of invaders. They aimed to enrich themselves and fought not only with the Irish but also among themselves. This continuous warfare gradually reduced the strength of the Normans, and no fresh settlers came to replace them. The Normans in remote areas began to adopt the language and customs of their Irish neighbors. Some Norman families adopted Irish names. The de Burgh family took the name Burke, and the Staunton family, McEvilly.

In 1366, Lionel, Duke of Clarence, son of King Edward III of England, summoned a parliament at the town of Kilkenny that passed laws forbidding the Normans to adopt Irish customs. The Statutes of Kilkenny, as these laws were called, also forbade the Normans to intermarry with the Irish, to speak the Irish language, or to wear Irish dress. But despite these laws, the number of Normans who adopted Irish ways of life continued to increase.

The Irish recovery.

After about 1350, the Irish chieftains began to recover their territories from the Norman barons. The Irish had acquired many of the weapons used by the Normans and had learned some of their tactics. They also hired Scottish soldiers, called gallowglasses, who were often stronger than the Normans (see Gallowglass). The MacCarthys regained power in Munster. Art MacMurrough Kavanagh became king of Leinster, and the O’Neill and O’Donnell families established strong kingdoms in Ulster.

By the early 1400’s, the area under the control of the English in Ireland was confined to a narrow stretch of territory on the east coast called the Pale or the English Pale. The Pale was the area surrounding Dublin, extending inland for no more than about 30 miles (48 kilometers). The lord deputy, who was the king’s representative, ruled over the Pale, and a parliament in Dublin passed laws for its people.

The Tudor conquest (1500’s-about 1600)

From 1455 to 1485, a civil war called the Wars of the Roses raged in England. The war was a battle between two branches of the English royal family over which of them should be king. Ireland was left largely undisturbed during this period. The Earl of Kildare, who was then lord deputy, became increasingly powerful. After the war, King Henry VII sent Edward Poynings, an English soldier and administrator, to Ireland as lord deputy. The king ordered Poynings to curb the power of the Earl of Kildare and to subdue the country. In 1494, Poynings summoned a parliament in Drogheda that passed laws forbidding the future Irish parliaments to be summoned or to introduce draft laws without the king’s prior consent. But the Kildare family remained powerful. The next English king, Henry VIII, summoned the Earl of Kildare to London. Henry goaded Kildare’s son, Silken Thomas, into rebellion and had most of the family hanged at Tyburn in 1537.

Under Henry VIII.

Beginning in 1529, King Henry VIII had a series of confrontations with Pope Clement VII. The pope had refused Henry’s request that he annul (cancel) Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. In 1533, Henry persuaded the English Parliament to declare that England was independent of all foreign authorities, including the pope. A church commission led by the Archbishop of Canterbury soon annulled the marriage. In 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, recognizing the king as head of the church in England. Henry tried to impose a similar policy on Ireland. Parliament also passed acts forbidding people to appeal to the Roman Catholic leadership in Rome or to make payments to the pope. Beginning in 1536, the British government suppressed a number of monasteries and confiscated their property. But, in areas under Irish rule, the king had little power, and few people even realized that any changes had taken place.

The political changes of this period affected people more than the religious changes did. The political changes were the work of the new lord deputy, Sir Anthony Saint Leger. He negotiated agreements with Irish chiefs and Anglo-Irish lords. Under these agreements, the chiefs and lords surrendered their lands to Henry and, as his vassals (feudal subjects), received the lands back from him. Many Irish chiefs agreed to recognize Henry as their overlord, and in return he gave them English titles. For example, Conn O’Neill became Earl of Tyrone and Murrough O’Brien became Earl of Thomond. To enact this new policy, the lord deputy summoned a parliament in Dublin in 1541 that gave Henry VIII the title king of Ireland. Henry was pleased with the success of this new policy, and for the rest of his reign he allowed the Irish and Anglo-Irish nobles to rule their lands. Henry also established English laws in Ireland.

Under Edward VI and Mary Tudor.

When Henry VIII died, his 9-year-old son, a sickly child, became king as Edward VI. Under Edward, Henry’s vassal system in Ireland continued, along with a policy of creating English garrisons (groups of soldiers stationed in a fort) along the boundaries of the Pale. This indicated that the English expected a long period of struggle with the Irish. After Edward’s death at the age of 15, Henry VIII’s daughter Mary succeeded to the throne in 1553. She decided to reverse this arrangement. She believed that the best way to subdue Ireland was to introduce colonies of English people into the country. In 1556, Mary tried to strengthen English rule of Ireland by a process called plantation, taking land from Irish owners and giving it to English colonists. She seized land in County Laois (also spelled Leix or Laoighis) and County Offaly in central Ireland and gave it to English settlers. She also renamed the counties Queen’s County, after herself, and King’s County, after her husband, King Philip II of Spain.

Under Elizabeth I.

Queen Mary was a fervent Roman Catholic who worked hard to restore the old religion in both England and Ireland. Her half-sister, Elizabeth, succeeded her in 1558. At first, Elizabeth was tolerant in her dealings with Roman Catholics. But from about 1575 onward, she adopted a harsher attitude. She outlawed Roman Catholic religious services and executed a number of bishops and priests. As a result, the Irish Catholics became more united and more bitterly anti-English than ever.

To strengthen England’s control of Ireland, Elizabeth decided on a plantation of Munster. She gave the land to English gentlemen called undertakers, who undertook (promised) to fill the lands with English settlers. Among the undertakers were the explorer and author Sir Walter Raleigh and the poet Edmund Spenser. But they could persuade few English farmers to live in the Munster plantation, and the plantation eventually failed.

In the later 1500’s, a series of revolts against the English broke out in Ulster, led by the Irish chieftains Hugh O’Neill of Tyrone and Red Hugh O’Donnell of Tyrconnell. O’Neill, believing that Elizabeth aimed to conquer Ireland, built up an alliance of the Ulster chiefs to oppose her. War began in 1595. In the early stages, O’Neill won victories at Clontibret in County Monaghan and at the Yellow Ford in Armagh, in what is now Northern Ireland.

In 1600, Elizabeth made Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, an English nobleman and soldier, lord deputy. She appointed Sir George Carew, another English soldier, president of Munster. Mountjoy strengthened English garrisons in the north and began to destroy crops and cattle in the area. Soon the English forces broke the power of the Irish chiefs who would have helped O’Neill. O’Neill was confined to Ulster, short of food, and blockaded from the sea by the English Navy. O’Neill’s only hope lay in the arrival of foreign aid. A force of 4,000 Spaniards landed at Kinsale, in Cork, but they came too late and landed too far from the center of Irish resistance in Ulster. On Christmas Eve, 1601, the English won a decisive battle against the Spanish forces. O’Donnell departed for Spain, where he died soon afterward. O’Neill formally surrendered at Mellifont in 1603. The defeat was a turning point in Irish history. It ended the power of the Irish chiefs and hastened the decline of the traditional Irish way of life.

Plantations and uprisings (1600’s)

During the 1600’s, plantations continued, and English and Scottish landlords took over much of Ireland’s land. But the Irish repeatedly rebelled.

The flight of the earls.

By the terms of his surrender at Mellifont, O’Neill gave up his Irish title, O’Neill, and took the title Earl of Tyrone—a title he previously held from 1587 to 1595. He was allowed to retain much of the land that had been granted to his grandfather, Conn O’Neill, in 1542. Rory O’Donnell, younger brother of Red Hugh, became Earl of Tyrconnell on the same terms. The two earls traveled to London, where the new king, James I, confirmed the Treaty of Mellifont. But the English officials who ruled Ulster were unfriendly and tried to turn the lord deputy in Dublin against the earls. They claimed that O’Neill and O’Donnell were planning another rebellion, and English officials summoned the earls for questioning. Fearing for their safety, the two Irishmen fled the country. In 1607, they sailed from Lough Swilly for the mainland of Europe with some 70 followers, including members of the leading families of Gaelic Ulster.

The plantation of Ulster.

James I tried to prevent further revolts by continuing the plantation of Ireland. After the flight of the earls, the government confiscated their lands and sent English colonists to settle six counties of Ulster—Armagh, Cavan, Coleraine, Donegal, Fermanagh, and Tyrone. The plantations of Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth I had not been successful, and the government planned the new settlement more carefully. It granted estates to three groups of people: (1) English and Scottish settlers, who were forbidden to have Irish tenants; (2) servitors, men who had served in the English army in Ireland, who were allowed to take both British and Irish tenants; and (3) Irishmen, who were forbidden to have Irish tenants. Rents were low, but English planners expected the settlers to build fortified houses.

The English government handed over the town of Derry to the City of London. London trade guilds sent master builders and money to rebuild the town, which, as a result, was renamed Londonderry. Protestant newcomers, many from the borderlands of northern England and southern Scotland, founded numerous towns in the area. At the same time, a privately funded venture brought people from Scotland to settle in two more counties of Ulster—Antrim and Down. The Ulster settlement was the largest and most successful of the plantations, creating a Protestant majority that existed in Northern Ireland until the early 2000’s.

The Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian settlement.

In the years that followed, the government made other settlements, in counties Carlow, Leitrim, Longford, and Wexford, and in King’s County (Offaly). Even Old English nobles, the descendants of Norman settlers, lost their lands. As a result of these plantations, Roman Catholic landowners became alarmed. None of them felt secure in their lands. Resentment toward the English government spread among the Roman Catholic community. The Catholics also feared that the Puritans, strict Protestants who were coming to power in Parliament, would persecute them. At the time, Parliament and King Charles I had been engaged in numerous longstanding conflicts over religious doctrine, tax policies, and other matters.

In November 1641, the Irish rebelled. Charles wanted to raise a new army to subdue Ireland, but Parliament did not trust him to command it. By 1642, a series of clashes between Charles and parliamentary leaders grew into the English Civil War. The Royalists—supporters of the king—and the armies of Parliament engaged in numerous battles in England and Wales.

In Ireland, the rebellion continued for 10 years. The Irish Catholics fought for independence. Many of the Old English joined them, but declared that they were loyal to the king and were fighting mainly for religious freedom. Irish Protestants were divided into two groups: those who supported the king, and those who supported Parliament. In 1642, the leaders of the rebellion formed the Confederation of Kilkenny and appointed Owen Roe O’Neill, a nephew of the Earl of Tyrone, and Thomas Preston, a Catholic of English descent, as generals. O’Neill won a great victory at Benburb, in County Tyrone, in 1646 (see O’Neill, Owen Roe).

By this time, the armies of Parliament had defeated the king’s main armies in England. In January 1649, Charles was convicted of treason and beheaded. In August, Oliver Cromwell, a Puritan general who had become the ruler of England, traveled to Ireland to put down the revolt. In September, Cromwell arrived at Drogheda, where he demanded the town’s surrender. After negotiations failed, Cromwell’s army took the town and massacred the garrison. Thousands of Irish soldiers were killed, including many after they had laid down their arms. Cromwell’s men also killed several hundred inhabitants, including most of the Catholic clergy. In October, Cromwell moved south and massacred the garrison of Wexford, a seaport 120 miles south of Dublin. Hundreds of residents were killed, and most of the survivors fled the town. Cromwell’s ruthlessness struck fear into Irish hearts, and many of the southern and eastern towns surrendered without a struggle. When Cromwell returned to England in 1650, the war was almost over, but the Irish army did not surrender for another two years.

The war left Ireland in a wretched condition. Most of its former leaders were either dead or living in exile, and about 30,000 of its armed men had left to join the armies of France or Spain. Thousands more were transported (deported) to the Caribbean and Virginia to work as indentured servants. Indentured servants worked without wages for a specific time. Many of the deported Irish toiled under harsh conditions for years, and few ever returned to Ireland.

Cromwell then confiscated the land of all the people who were shown to have assisted in the 1641 Rebellion. Nearly half of the land of Ireland was confiscated from the Catholics born in Ireland and given to Protestants born in England. Much of the land went to Cromwell’s soldiers, and the rest went to a group called adventurers, Englishmen who had contributed money to pay for Cromwell’s campaign in Ireland. Cromwell abandoned a plan to move all Catholic tenants and laborers to Connacht, however. He allowed only tenants, tradespeople, and laborers to stay, but stripped them of all political rights.

Cromwell’s settlement was not a complete success. Many of the English settlers sold their farms and returned home. Others married into Irish families, and their descendants lost their English characteristics. But the settlement did succeed in creating a new Protestant landlord class. Before 1641, Roman Catholics owned about three-fifths of the land. By the 1680’s, they owned only one-fifth of it.

When King Charles II came to the throne in 1660, there was some softening of the persecution of Catholics. Priests were no longer threatened with execution and deportation. The laws prohibiting Catholic worship were not enforced, as long as the Catholic services were conducted in private. But Catholics remained banned from taking any part in politics or the law.

The Williamite War.

The Irish welcomed King James II to the English throne in 1685. James was a Roman Catholic, and the Irish Roman Catholics hoped that he would enable them to recover their lands. James appointed a Catholic soldier, Richard Talbot, as lord deputy. James made him Earl of Tyrconnell and instructed him to give Catholics a fairer share of political power in Ireland. Talbot carried out the king’s instructions and also built up a large Roman Catholic army.

In 1688, the British people drove out James and offered the throne to William of Orange, a Protestant Dutch prince who was both his nephew and his son-in-law (see Glorious Revolution). James fled to France. In the following year, he went to Ireland with French support, in the hope that the Roman Catholics would help him recover his throne. The Protestants of Ireland proclaimed their allegiance to King William III and fortified the towns of Londonderry and Enniskillen against James. The Protestants became even more defiant when they learned that James had summoned a parliament in Dublin. He planned to use the parliament to give the majority Roman Catholic population control of the political institutions of Ireland. But he hesitated to reverse the land settlements made over the previous 80 years.

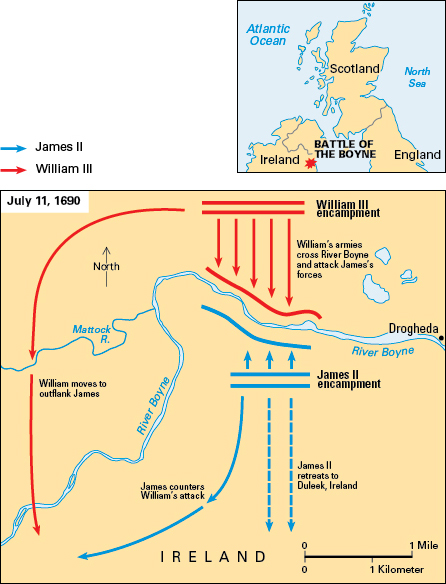

In 1689, James besieged Londonderry for three months but failed to take it. In the following year, William landed at Carrickfergus, in Antrim, with a large army to fight James. The war, known as the Williamite War, was short and decisive. William defeated James at the Battle of the Boyne, and James returned to France (see Boyne, Battle of the). The Irish and their French allies continued the fight. But William’s forces defeated them again at Aughrim and drove them back to Limerick. Patrick Sarsfield, Earl of Lucan, defended the town, but when no French help arrived, he surrendered.

On Oct. 3, 1691, the two sides signed the Treaty of Limerick. The treaty gave James’s supporters three choices: (1) to take an oath of loyalty to William and return to their homes and lands; (2) to enlist in William’s forces; or (3) to go to France. Several thousand of them accompanied Sarsfield to France. Many of them later won fame on the battlefields of Europe. The treaty also granted security of property and religious freedom to Catholics in Ireland. William intended to honor the treaty, but the English Parliament considered it too lenient and did not honor it. See Limerick, Treaty of.

Two nations (1700’s)

During the 1700’s, Protestant landowners gained even greater wealth and power at the expense of Irish Catholics and the heirs of the Puritan and Presbyterian settlers from England and Scotland. Irish nationalists began to emerge from among these groups and to campaign for greater rights.

The Penal Laws.

After the Williamite War, the English government confiscated more land from the Irish Roman Catholics. By 1704, Irish Catholics owned no more than one-eighth of the land. Beginning in 1691, the British government passed a series of harsh religious laws known as the Penal Laws. The laws banished bishops and members of religious orders from their communities.

Other laws aimed to keep Roman Catholics poor and without power. When a Catholic landowner died, his estate had to be divided equally among his sons. If the eldest son became Protestant, however, he inherited the estate. No Catholic could purchase or lease land for more than 31 years. Catholics could not carry arms or own a horse worth more than a small amount of money. They were forbidden to teach in schools or send their children abroad to be educated. They were not allowed to become members of Parliament or vote in parliamentary elections. They could not hold any government office, serve on a jury, or become a lawyer or army officer. Through these laws, the Protestant minority hoped that Roman Catholicism would die out.

By the 1770’s, Roman Catholics made up a large majority of the population but held only one-twentieth of the land. A few prospered in trade, but most were tenant farmers. These farmers paid high rent to their Protestant landlords and also paid tithes (contributions of one-tenth of their earnings) to the Protestant church. Other Roman Catholics were landless laborers living in great poverty. As the population grew, competition for land increased. Many poor people lived on potatoes and little else.

After the Irish aristocracy lost their lands, the use of the Gaelic language declined. Although the lower classes still spoke Gaelic, the ruling class and the Protestants in Ulster used English.

The Presbyterians of Ulster were allowed to vote in parliamentary elections, and a few of them became members of Parliament. The Presbyterians were Protestants who followed Calvinist teachings and did not belong to the state Protestant church. Most were descendants of immigrants from Scotland. The Presbyterians did not have full civil rights, and they had to pay tithes. Thousands of them became discontented and moved to the American Colonies.

Protestant rule.

The Protestant landowning class created by the plantations ruled Ireland. But the British government did not allow them complete freedom. The British put restrictions on Irish trade and supported only the linen industry. The Irish Parliament could not pass laws without the permission of the British government, and in 1719 the British Parliament claimed the right to make laws for Ireland. At first, the Protestant ruling class felt too insecure to protest. But gradually some members of the Irish Parliament, who became known as Patriots, began to resent the restrictions on their power.

When the American Revolution broke out in 1775, the British government withdrew troops from Ireland to serve abroad. The Protestant landlords formed armed groups called Volunteers to defend the country. The Patriots gained control of the Volunteers. With help of the two groups, an Irish politician named Henry Grattan forced the British government to remove the restrictions on Irish trade and on the Irish Parliament (see Grattan, Henry).

In 1782, the Irish Parliament began 18 years of independence. These were prosperous years for some parts of Ireland. Parliament tried to increase prosperity by providing financial support for Irish industries. But most of the Irish people had little share in this prosperity.

Political instability.

The Irish Parliament was corrupt. The lord lieutenant of Ireland controlled its decisions by distributing titles, jobs, and pensions among its members. The Parliament did not fairly represent all groups of Irish people. By this time, the British Parliament had repealed most of the Penal Laws. Penal Laws had barred Catholics from military service, teaching, studying law, or intermarrying with Protestants. Roman Catholics got the vote in 1793, but they could not become members of Parliament.

After the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, a radical movement in Ireland began to advocate more extreme political reforms. The movement was particularly strong among the Presbyterians of Ulster. In 1791, a young Dublin lawyer, Theobald Wolfe Tone, founded the Society of United Irishmen. The United Irishmen wanted to unite Irish people of all religious beliefs and to make Parliament representative of all the people. Later, they decided to establish an Irish republic with French help. A French force landed in County Mayo in 1798 and staged a brief rebellion near Castlebar. The battle is called the Races of Castlebar because the French forces chased the retreating British forces through the streets of Castlebar. But British forces soon defeated the French and United Irishmen. The British brutally suppressed the rebellion, killing or wounding thousands.

The struggle for rights (1800’s)

The British government decided to resolve problems in Ireland by uniting the two kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland under the Act of Union. To persuade the Irish Parliament to pass the act, British prime minister William Pitt promised that Great Britain would grant political rights to Roman Catholics. Under the act, which went into effect in 1801, Ireland officially became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The Irish Parliament was then ended, and Ireland sent representatives to the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Catholic emancipation.

The union disappointed most of the Irish. The United Kingdom’s Parliament did not honor Pitt’s promise to the Roman Catholics, and political union did not bring economic prosperity. As the Irish population grew, more people needed land. Irish industries could not compete with British ones, which were more efficient. The only part of Ireland to benefit from the union was Ulster. There the linen industry expanded, and new industries grew up and prospered.

Daniel O’Connell, a Roman Catholic lawyer, argued for the emancipation of Catholics as a step toward the relief of Ireland’s problems. But O’Connell had witnessed the terror of the French Revolution, and he therefore favored a peaceful and orderly solution to Ireland’s problems. He believed that the country’s problems would not receive adequate attention until the British Parliament accepted Roman Catholics and until Ireland had a parliament of its own. In 1823, he formed the Catholic Association to work for full political rights for Roman Catholics. Many of the Irish people, but not the Protestants of Ulster, backed him.

In 1828, O’Connell won a by-election (special election to fill a vacant seat) in County Clare but was not allowed to take his seat as an elected member of Parliament. The British government feared a revolution in Ireland if O’Connell could not sit in Parliament after being duly elected. In 1829, Parliament passed an act allowing Catholics to sit in Parliament and to hold all government offices except those of regent, lord lieutenant, and lord chancellor. O’Connell became known as “the Liberator” and “the uncrowned king of Ireland” for his work helping Irish Catholics gain political rights. At the same time, however, the government changed the property and income qualifications for voting, and many tenants in Ireland lost the right to vote.

The Young Irelanders.

Initially, O’Connell had the support of a group of young men called the Young Irelanders, who promoted Irish nationalism. In 1842, three of them, Thomas Osborne Davis, a lawyer; John Blake Dillon, a newspaper editor; and Charles Gavan Duffy, a historian and journalist, founded a newspaper called The Nation. The paper’s goal was to awaken interest in Irish nationalism, Catholic emancipation, and independence from British rule.

The Young Irelanders tried to win Protestant support, but most Protestants opposed them. They gradually came to believe in the use of force to make Ireland independent. In 1848, a group led by William Smith O’Brien, a member of Parliament, tried to raise a rebellion. They failed, and the government deported O’Brien and some of the other leaders to Tasmania, an island that is now part of Australia.

The Great Irish Famine.

In 1801, the population of Ireland was about 5 million. By 1841, it had risen to more than 8 million. There were few industries, so the country depended largely on agriculture. As the population grew, farms decreased in size. Most of the people lived as tenants on small farms. They had to give much of what they produced to their landlords as rent. Most of the tenant farmers struggled to survive on what was left from their production.

Because of their poverty, many of the Irish people depended largely on potatoes for food. Some raised animals and grew grain to pay their rents. In 1845, 1846, and 1848, blight (disease) affected the potato crop throughout the country. The potatoes rotted, and millions of people faced starvation.

The British prime minister, Sir Robert Peel, introduced relief plans in the poorest areas. These plans were meant to help people earn enough money to buy grain that the government imported from the United States. But these measures were inadequate, and the next government, under Lord John Russell, had to distribute food free of charge. These relief measures were also inadequate. Hundreds of thousands of people died.

As a result of the Great Famine, the population of the country dropped from 8 1/4 million to 6 1/2 million. Historians believe that a million people died of hunger and disease. Millions emigrated, most of them to the United States and Canada. They left Ireland with bitterness in their hearts, believing that the United Kingdom was the cause of all their suffering. See Great Irish Famine.

The Fenians.

The Fenian movement was founded in Ireland and New York in 1858. Exiles in the United States led by an Irish nationalist named John O’Mahony formed the Fenian Brotherhood. This group was a secret, oath-bound society that aimed to establish an independent Irish republic, if necessary by force. At the same time, a civil engineer and Irish nationalist named James Stephens founded a similar organization in Dublin, called the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The two movements soon merged. At the end of the American Civil War (1861-1865), some disbanded soldiers joined the Fenians, and other members were recruited from the British Army.

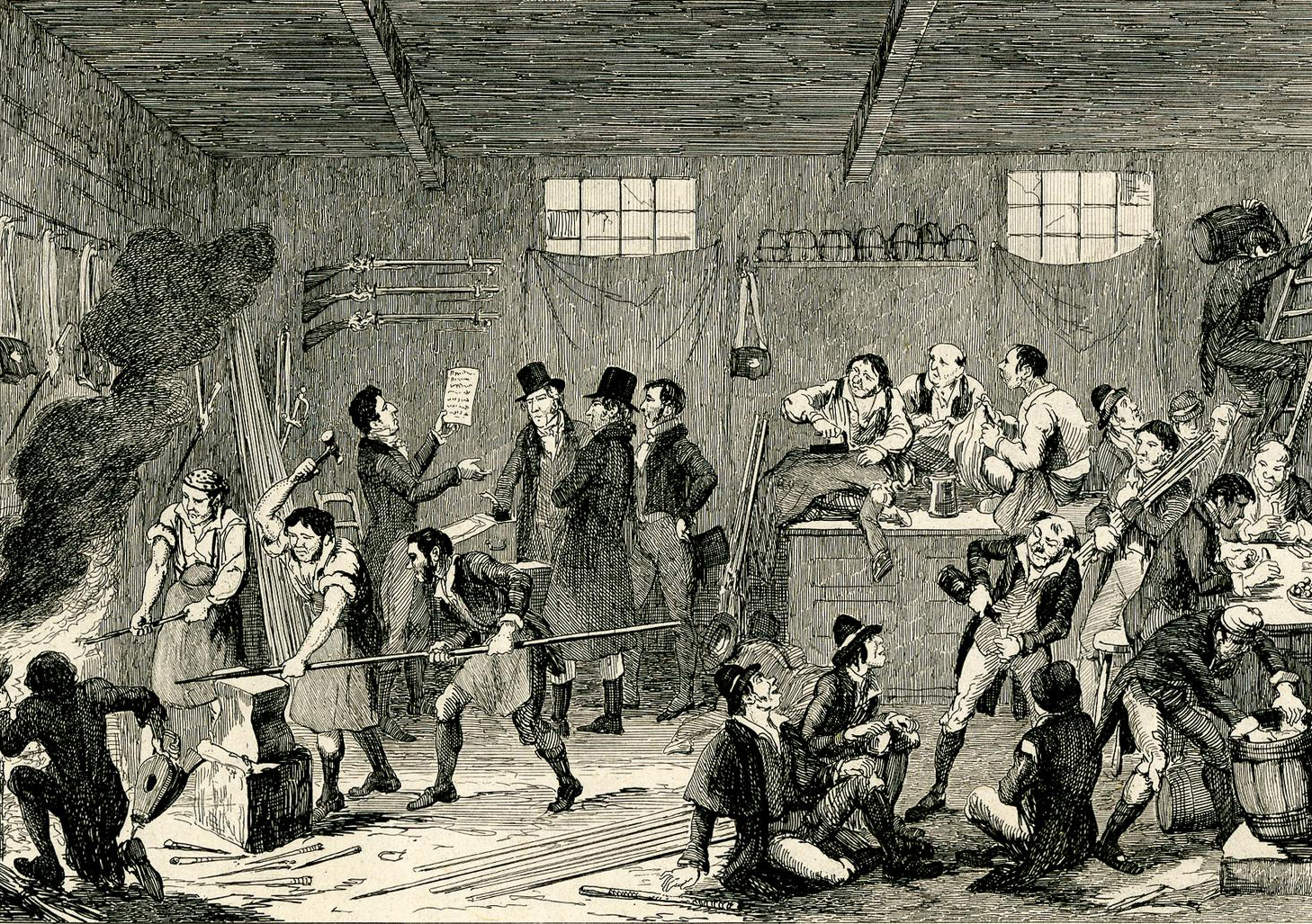

The Fenians smuggled ammunition into Ireland and made plans for an uprising. But spies kept the government informed of their preparations, and in 1865 several of the leaders were arrested. An uprising took place in 1867, but it was soon suppressed. The Fenian movement failed. But together with the Great Famine and resulting violence against landlords, the movement drew the attention of British statesmen to the need for reforms in Ireland. See Fenian movement.

Home rule and the Land League.

William Gladstone, who became prime minister of the United Kingdom in 1868, was greatly concerned about the outbreaks of violence in Ireland. He tried to calm the country by passing a Land Act that gave tenants some security. He also disestablished the Church of Ireland—that is, abolished its connection with the state. But the Irish were not satisfied.

In 1870, Isaac Butt, a Protestant lawyer, founded the home rule movement. Under home rule, Ireland would remain part of the United Kingdom but would have its own parliament in Dublin to deal with Irish affairs. Such matters as defense and foreign policy, and the taxes to sustain them, would remain under the control of the British government. Butt was a poor leader, and the home rule movement made little progress until 1879, when a young Protestant landlord, Charles Stewart Parnell, took control. See Butt, Isaac.

In 1879, the nationalist leader Michael Davitt founded the Irish National Land League to protect tenant farmers against high rents and eviction (being forced off their land by the landowner). Parnell merged the home rule movement and the Land League. He gained the support of many Fenians and received aid from the United States. The group increased its activities. In the British House of Commons, home rule supporters often interrupted the business of Parliament to force the British to address the issue of home rule.

In 1881, the British government, under Gladstone, passed a second Land Act, establishing courts to fix fair rents. But the Irish demand for self-government continued. On May 6, 1882, Irish terrorists murdered two British officials, Lord Frederick Cavendish, chief secretary of Ireland, and T. H. Burke, the undersecretary, in Phoenix Park in Dublin.

Gladstone introduced a Home Rule Bill in 1886. His party split over support of the bill, the bill was defeated, and Gladstone resigned. Four years later, Parnell became involved in a controversial divorce case, and his reputation and influence were ruined. Two years later, the Liberal government under Gladstone introduced another Home Rule Bill. The House of Commons passed the bill, but the House of Lords rejected it. Irish Protestants bitterly opposed both of these Home Rule bills.

The Conservatives, who held office in the British Parliament from 1895 to 1905, adopted a policy of “killing home rule by kindness.” Through this policy, the government introduced bills they hoped would satisfy the supporters of home rule without actually granting them self-rule. They passed acts to enable tenants to buy their lands. The most important act was Wyndham’s Act of 1903, which provided long-term, low-interest loans to enable tenants to purchase land. But the Irish people still wanted self-government.

Nationalism gains strength (1900-1920’s)

During the early 1900’s, Irish nationalists fought to win Ireland more control over its own affairs.

The Irish Parliamentary Party.

Parnell’s followers reunited under John E. Redmond, a lawyer and member of Parliament, in 1900. His party, the Irish Parliamentary Party, combined many of the parties calling for Irish home rule and gained the support of most of the Irish people. In 1906, the Liberal Party returned to power in the British Parliament. In 1911, it passed a Parliament Act, limiting the powers of the House of Lords, so that a bill would become law if passed by the House of Commons in three successive sessions. In 1912, the House of Commons passed a third Home Rule Bill. Though rejected by the House of Lords, it became law in 1914. By this time, new Irish nationalist movements, calling for the creation of an Irish republic, had emerged.

The Gaelic League.

In 1893, Douglas Hyde, an Irish writer, and Eoin MacNeill, a scholar of Irish history and literature, founded the Gaelic League to preserve and extend the use of the Irish language. The organization was not political, but many of the young men who joined it became nationalists.

Sinn Féin.

In 1899, Arthur Griffith, a Dublin journalist, started a weekly newspaper called The United Irishman, in which he advised the people of Ireland to become more self-sufficient. He wanted the Irish members of Parliament to stop attending the House of Commons and to set up an independent Irish council called the Council of Three Hundred. He intended this council to take over as much of the government as possible from British control. Griffith did not seek to create an independent Irish state. His aim was to restore the constitution of 1782, created during the 18 years of independence for the Irish Parliament.

In 1905, Griffith founded a party called Sinn Féin << shihn fayn >> (We Ourselves) to support his views, but at first it had little success. He did not believe in the use of force to achieve political aims, but many of his followers did. See Sinn Féin.

The Labour Party.

James Connolly and James Larkin, two trade union leaders, along with William O’Brien, a journalist and member of Parliament, founded the Labour Party in 1912. The party was the political wing of the Irish Trade Union Congress, an organization for Irish workers. The Labour Party supported socialist policies, focusing on such issues as poverty, unemployment, and emigration.

The Volunteer movements.

The Protestants of Ulster were determined to resist home rule. They chose a dynamic leader, Sir Edward Carson, an Irish lawyer and politician who later became Baron Carson of Duncairn. Carson formed a provisional (temporary) government to rule Ulster if the Home Rule Bill became law. They formed the Ulster Volunteer Force and imported arms from Germany, in case the British government insisted on home rule. See Carson, Lord.

Radical nationalists in the south followed Ulster’s example and formed an armed group called the Irish Volunteers, which would later become the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The Irish Volunteers imported arms just as the Ulster Volunteer Force did. In 1914, World War I broke out, and the British government agreed to postpone the start of home rule until the war was over. Most of the Irish Volunteers followed the example of John Redmond and supported the United Kingdom in the war.

The Easter Rising.

The rest of the Volunteers came under the control of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a secret organization that was preparing for rebellion. The leaders of the group were the revolutionaries Thomas J. Clarke and Seán MacDiarmada (also spelled MacDermott), and Padraic (also spelled Patrick) Pearse, an educator and writer. The three leaders decided to start a rebellion on Easter Sunday, April 23, 1916. Roger Casement, a former official in the British consular service who had become an Irish revolutionary, had gone to Germany for help, and the leaders hoped the uprising would coincide with the arrival of German arms. They did not reveal their plans to the head of the Volunteers, Eoin MacNeill, by then a professor of Irish history at University College Dublin.

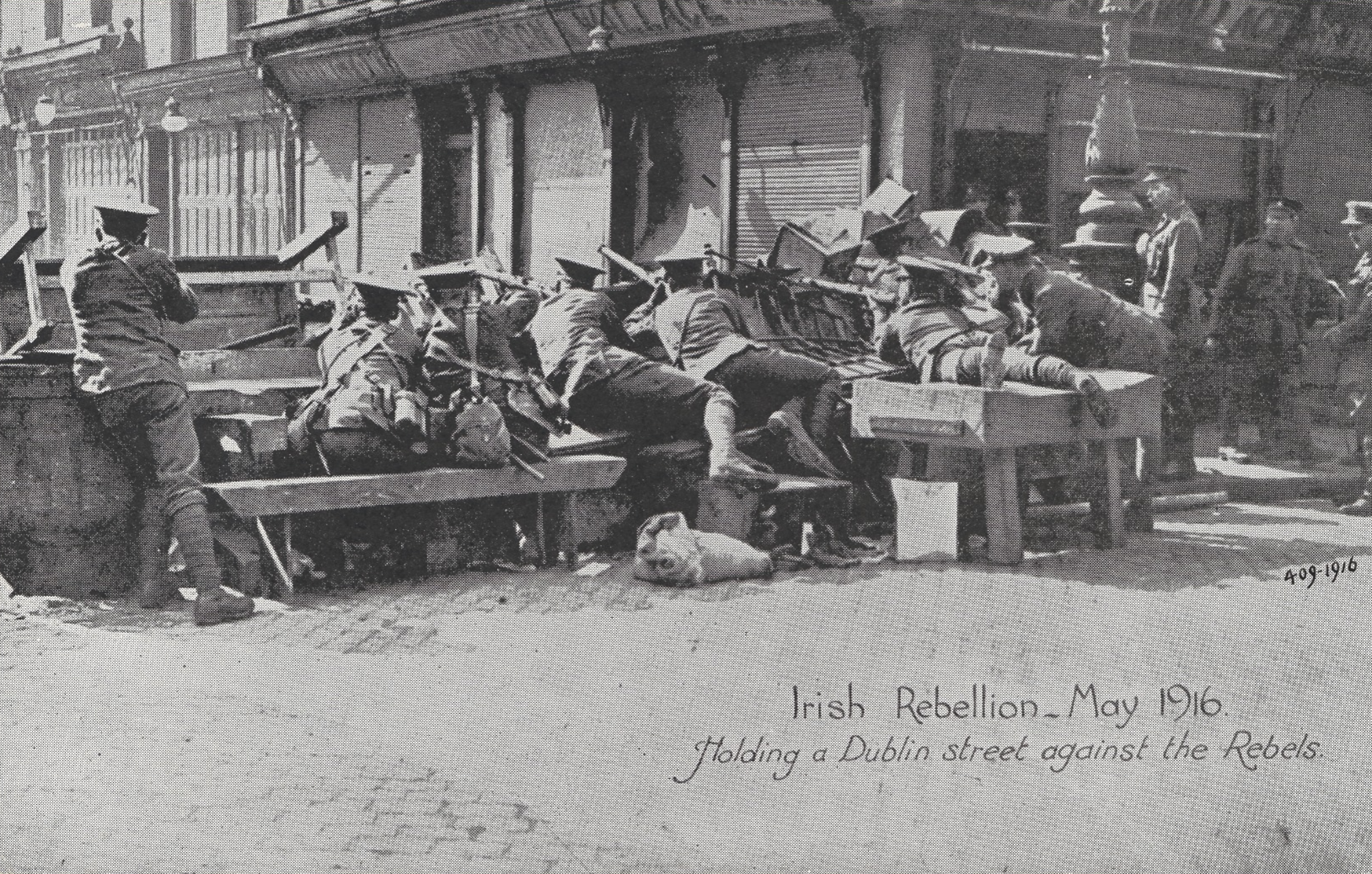

On Good Friday, Casement was arrested shortly after landing in County Kerry. MacNeill then heard of the planned rebellion and tried to stop it. His orders caused confusion among the Volunteers outside the Dublin area. But the uprising took place on Easter Monday. The Volunteers hoisted the Republican flag over the General Post Office in Dublin, and Pearse read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. British troops crushed the rebellion within one week. Fifteen of the leaders, including Pearse, were shot. Roger Casement was hanged in London. Another leader, Eamon de Valera, was sentenced to death, but the government later released him.

The War of Independence.

At first, the uprising had little backing, but the execution of the leaders increased the people’s support for the republican movement. In 1917, Sinn Féin declared itself in favor of an Irish republic. At the general election in the following year, Sinn Féin won 73 of the 105 Irish seats in the House of Commons. The Irish Parliamentary Party held only 6 seats. Instead of going to London to take their seats in Parliament, the new members formed a parliament in Dublin and elected de Valera as its president. The Irish Volunteers became the Irish Republican Army. Following the declaration, fighting broke out between the Irish rebels and British forces.

In 1920, the British Parliament under Prime Minister David Lloyd George passed the Government of Ireland Act. This act divided Ireland into two territories—one consisting of 6 counties of Ulster and the other consisting of 3 counties of Ulster and 23 southern counties. Each territory was to remain part of the United Kingdom and have some powers of self-government. The 6 Ulster counties, which had a Protestant majority, accepted the act and formed the state of Northern Ireland. The Irish Parliament rejected the act, and southern Ireland began fighting for complete independence.

Prime Minister Lloyd George sent over a large force of auxiliary police, recruited from former soldiers, to enforce the Government of Ireland Act. This force became known as the Black and Tans because they wore black-and-tan uniforms. They used extreme cruelty in dealing with the rebels, and the Irish people hated them bitterly (see Black and Tans). Lloyd George sent over another force, recruited from former officers, who became known as Auxiliaries. Almost two years of bitter guerrilla warfare followed, until a truce was declared on July 11, 1921.

The Treaty of 1921.

To negotiate a settlement, the Irish Parliament sent Arthur Griffith, the founder of Sinn Féin; Michael Collins, another Sinn Féin leader; Eamonn Duggan, a lawyer; Robert C. Barton, a landowner; and the historian George Gavan Duffy to London. On Dec. 6, 1921, British and Irish representatives signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London. Under the treaty, the 26 counties of southern Ireland became a dominion (self-governing country) of the British Commonwealth called the Irish Free State. The six counties of northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom, with limited self-government. By the terms of the treaty, a governor general would represent the British monarch in the Irish government. The members of the Irish Parliament would take an oath of allegiance to the British monarch. The British Navy would retain control of some Irish ports. The treaty caused a split in the Sinn Féin party, and the Irish Parliament ratified it a month later by only 64 votes to 57.

Independence (Since the 1920’s)

In the 1920’s, Ireland emerged as an independent nation. But in the years after independence, the nation faced many problems, including economic downturns and decades of violence in Northern Ireland.

The Irish Free State.

The 1921 treaty that created the Irish Free State sharply divided the Irish people. One group, led by Eamon de Valera, wanted complete independence from the United Kingdom and union with Northern Ireland. The other group, led first by Michael Collins and later by William T. Cosgrave, supported the treaty.

After the Irish Parliament ratified the treaty on Jan. 7, 1922, de Valera resigned as president and Arthur Griffith succeeded him. A week later, a provisional government was established, under the leadership of Michael Collins, to take over authority from the British. But the country did not find peace. The Free Staters, who supported the treaty, and the Republicans (also known as the “anti-Treatyites”), who opposed it, continued to disagree. The country drifted into disorder, and in June 1922 a civil war began.

The civil war was a tragic end to the struggle for freedom, resulting in the loss of many lives. Griffith died of a stroke. Collins was killed in an ambush in the county of Cork. The war went on until April 1923, when IRA Chief of Staff Frank Aiken, supported by de Valera, ordered Republican forces to stop fighting. The IRA continued to operate as an underground organization.

From 1922 until 1932, William Cosgrave served as president of the Executive Council, which governed the Irish Free State. His government improved the Irish economy and established close trade relations with the United Kingdom. De Valera and his followers took no part in the early proceedings. They did not take their seats in the Irish Parliament, because they would not take an oath of allegiance to the British king.

In 1926, de Valera abandoned his attempt to abolish the oath of allegiance. He resigned from Sinn Féin and formed a new party called Fianna Fáil << FEE uh nuh FAWL >> (Soldiers of Destiny). He announced that he and his party intended to join the Irish assembly but dismissed the oath of allegiance. Cosgrave led a party called Cumann na nGaedheal << koo MAHN na GAYL >> (Community of Gaels), a name later changed to Fine Gael << FIHN uh GAYL >> (Tribe of the Gaels).

The Fianna Fáil Party won the general election in 1932, and de Valera became president of the executive council. A political and trade conflict called the Economic War began soon afterward. The Irish Free State stopped paying land annuities—that is, repayments of loans made by Britain to Irish tenant farmers—to the British government. De Valera sought to use the funds to invest in the Irish economy. Britain, in response, levied import duties on Free State goods—particularly cattle and other livestock. The Irish Free State then placed duties on British coal, cement, and other goods. Ireland’s economy suffered severely. Unemployment soared, and emigration increased. De Valera cut many political and ceremonial ties between the Irish Free State and the United Kingdom. He eliminated the oath of allegiance to the British monarch and abolished the office of British governor general of Ireland.

In 1937, de Valera’s government adopted a new constitution that described Ireland as a “sovereign, independent, democratic state.” The document changed the state’s name from the Irish Free State to Éire, the Gaelic word for Ireland. The office that was called president of the Executive Council became taoiseach << TEE shok >>, the Gaelic term for chieftain, used to describe the head of government or prime minister. The people approved the Constitution in a referendum, and de Valera became taoiseach. In 1938, the Irish and British came to an agreement that ended the land annuities and removed duties on imports. The British government also returned control of Irish ports that they had taken over under the Treaty of 1921.

The Republic of Ireland.

In 1948, John A. Costello, the leader of Fine Gael, became taoiseach. On April 18, 1949, his government cut all ties with the United Kingdom and declared Ireland an independent republic.

The political leaders in the Republic of Ireland supported the reunification of the country by peaceful means. But the Irish Republican Army regrouped and tried to end the division of the island by force. The IRA launched guerrilla attacks in Northern Ireland from the 1930’s until the late 1990’s.

Fianna Fáil and de Valera returned to power in 1951, lost to Fine Gael and Costello in 1954, and then returned to power again in 1957. In 1959, de Valera resigned as taoiseach and was elected president. Fianna Fáil kept control of Parliament until 1973. Since then, control of Ireland’s government has switched back and forth between Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil. Usually, these parties have had to form coalitions with smaller groups to have a majority of the votes in Parliament.

Economic development.

In the mid-1900’s, agriculture remained the main industry in the Republic of Ireland. Irish leaders implemented policies to create a more balanced economy. They encouraged the growth of new industries and introduced tariffs (taxes on imports or exports) to help Irish manufacturers. They also formed state-sponsored companies to undertake essential projects and encouraged firms from other countries to establish new industries in Ireland.

From 1926 to 1960, the number of people employed in industry increased by about 100,000. But in the same period, the number of people working on the land dropped by about 250,000. Enough jobs could not be created for these people, and thousands of Irish workers emigrated, mainly to the United Kingdom and the United States. By the 1960’s and 1970’s, the development of new industries had further improved job opportunities in Ireland. Emigration rates began to slow.

In 1973, Ireland joined the European Economic Community (EEC). The EEC, an economic organization of European nations, was also known as the Common Market. In 1993, Ireland and the other EEC countries formed the European Union, which works for both economic and political cooperation among its members.

In the 1980’s, Ireland’s economy again struggled with high unemployment, and many people left the country to find work elsewhere. In 1991, the government introduced a program to stimulate economic growth. The economy then began to grow steadily. By the late 1990’s, Ireland had one of Europe’s strongest economies, earning it the nickname Celtic Tiger. Pharmaceutical industries, technology companies, and financial and investment firms established their European centers in Ireland. Ireland’s unemployment rates fell to levels below the average for the other European Union countries. Emigration from Ireland decreased, and immigration from other countries increased.

Conflict in Northern Ireland.

In the late 1960’s, demonstrators in Londonderry, Belfast, and other Northern Ireland cities held protests against unfairness in public housing and jobs programs. The protests were part of a new civil rights movement seeking equal rights for Catholics in Northern Ireland. Police violently quashed many protests, which had drawn strong support from neglected Catholic neighborhoods. The clashes led to conflict that many came to see as a fight between nationalists and unionists. Nationalists wanted Ireland and Northern Ireland to reunite. Unionists sought to maintain Northern Ireland’s ties to the United Kingdom. Most nationalists were Catholic, and most unionists were Protestant, but there were significant exceptions. Illegal paramilitary organizations on both sides engaged in violence. The British Army arrived to keep order and clashed with the IRA and the Irish National Liberation Army. The IRA staged bombings, kidnappings, and other terrorist acts in Northern Ireland and Britain. Unionist groups, such as the Ulster Defence Association and the Ulster Volunteer Force, also carried out deadly attacks.

In 1976, the Irish government passed laws that increased the punishment for membership in the IRA and for terrorist acts. In 1985, the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement, which established an advisory council for Northern Ireland (see Anglo-Irish Agreement). The council gave Ireland an advisory role, but no direct powers, in the government of Northern Ireland. All parties in Ireland widely accepted the agreement, but unionists in Northern Ireland bitterly opposed it. Also in 1985, a new political party, the Progressive Democrats, formed in Ireland. The Progressive Democrats supported generally conservative policies, such as tax reductions and a decreased role of the government. The party dissolved in 2009.

Northern Ireland peace process.

In elections in 1987 and 1989, the Fianna Fáil party won the most seats in the Irish Parliament but failed to gain a majority. In 1989, Charles Haughey, leader of the party, became taoiseach of a coalition government—that is, a government in which more than one party shares power—formed by Fianna Fáil and the Progressive Democrats. In the early 1990’s, the coalition collapsed, and support for Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael decreased. The Labour Party gained in popularity and entered a coalition government with Fianna Fáil in 1993, with Fianna Fáil leader Albert Reynolds as taoiseach.

Reynolds’s greatest success in office was his work toward peace in Northern Ireland. In 1993, he and British prime minister John Major signed the Downing Street Declaration, an agreement setting out terms for peace in Northern Ireland. In 1994, Reynolds resigned over controversy surrounding his appointment of a High Court president. Reynolds was replaced by Fine Gael leader John Bruton at the head of a coalition with the Labour Party and the Democratic Left. Fianna Fáil formed a coalition government with the Progressive Democrats in 1997, with Fianna Fáil leader Bertie Ahern as taoiseach. Ahern was reelected in 2002, but Fianna Fáil narrowly failed to win a majority in the Irish Parliament.

In 1998, peace talks on Northern Ireland concluded in an agreement, known as the Good Friday Agreement or Belfast Agreement, that promised an end to the conflict in the troubled region. The talks ended the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement and established a North-South Ministerial Council that consists of representatives from Ireland and Northern Ireland. This council meets to administer policies that concern the entire island of Ireland. Full implementation of the agreement began in late 1999. The United Kingdom ended direct rule of Northern Ireland, transferring control of most local matters to the new Northern Ireland Assembly. The Republic of Ireland, in turn, amended its Constitution and gave up its claim to Northern Ireland.

For their work shepherding the peace process, Northern Ireland politician John Hume, a moderate nationalist, shared the 1998 Nobel Peace Prize with David Trimble, leader of the Ulster unionists. Other key figures in the peace negotiations included Ahern; United Kingdom prime minister Tony Blair; United States president Bill Clinton; George Mitchell, the United States special envoy for Northern Ireland; Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams; and Marjorie “Mo” Mowlam, United Kingdom secretary of state for Northern Ireland.

The 2000’s.

Ireland enjoyed rapid economic growth into the early 2000’s. But growth slowed in 2008 when the global economy entered a recession. Many technology companies, which had played a large role in Ireland’s economic growth, slowed or stopped their expansion. Beginning in 2008, Ireland’s property market collapsed, and bad debts severely hampered the nation’s banks. By 2010, Ireland’s financial problems threatened to worsen debt crises in other European countries. The Irish government sought financial help from the European Union, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Ireland agreed to drastically reduce spending in exchange for an 85-billion-euro ($112-billion) financial rescue package.

In the 2007 elections, Fianna Fáil won the most seats in the Irish Parliament, and Bertie Ahern remained as taoiseach. Because Fianna Fáil did not win a majority of votes, Ahern established a coalition government with the Green Party, the Progressive Democrats, and some independent politicians. In 2008, Ahern announced his resignation as taoiseach and Fianna Fáil leader. Brian Cowen succeeded him. The government’s agreement to the spending reductions was unpopular among the public and proved politically difficult for the party. In 2011, amid severe economic troubles, Cowen resigned as Fianna Fáil leader. Fianna Fáil lost in elections to Fine Gael, which formed a coalition government with the Labour Party. Fine Gael leader Enda Kenny then succeeded Cowen as taoiseach.

In 2015, Irish voters approved a referendum legalizing same-sex marriage. In 2016 elections, Fine Gael won the most seats in parliament but failed to win a majority. Fine Gael then negotiated a minority government with Fianna Fáil, and Kenny remained taoiseach. Kenny stepped down as Fine Gael leader in 2017. He was replaced by Leo Varadkar, who then became Ireland’s new taoiseach.

In the 2020 general election, the seats in parliament were split three ways, between Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, and Sinn Fein. The election marked the first time Sinn Fein had so strongly challenged Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. Weeks later, after Varadkar finished third in a parliamentary vote for taoiseach, he announced that he would resign from the position when a successor was named. In June, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael formed a coalition with the Green Party, and Fianna Fáil’s Micheál Martin succeeded Varadkar as taoiseach. As part of a coalition governing agreement, Varadkar became taoiseach again in December 2022. He served in the position until 2024, when Simon Harris became Fine Gael leader and taoiseach.

Beginning in 2020, Ireland faced a public health crisis due to the spread of COVID-19, a contagious respiratory disease. Efforts to contain the spread of the disease caused great strain to the country’s economy. In March, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a pandemic—that is, a global epidemic. Irish leaders closed schools and recommended social distancing measures to control the spread of the virus. By the end of March, cases had been confirmed in all of Ireland’s counties. Authorities announced the closure of all businesses deemed nonessential and recommended that residents leave their homes only in limited circumstances. In May, as COVID-19 infections in the country declined, the government relaxed some restrictions on business and leisure activities. In the months that followed, officials raised or lowered restriction levels based on the severity of infection rates.

By 2021, the acquisition and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines became the government’s major focus. Ireland’s vaccination rate improved during the spring and summer, contributing to lower rates of infection and death. The spread of new, more contagious variants of the virus, however, later contributed to spikes in infection rates. Nearly all Covid-19 restrictions were eased in late February 2022. On March 18, the country held a day of remembrance and recognition in memory of the people who had died of COVID-19, and to thank the volunteers and workers who helped fight against the disease. A 2020 law that granted the government emergency powers to combat the pandemic expired in April 2022. By early 2023, more than 1,700,000 COVID-19 cases had been confirmed in Ireland, and more than 8,000 people had died from the disease.

In February 2023, the Irish people for the first time celebrated Imbolc/Saint Brigid’s Day as a bank holiday (legal holiday). The holiday celebrates both Imbolc, a Celtic pagan festival marking the traditional start of spring, and Saint Brigid, one of Ireland’s patron saints. The holiday, which takes place on the Monday closest to February 1, is the first Irish public holiday named after a woman.