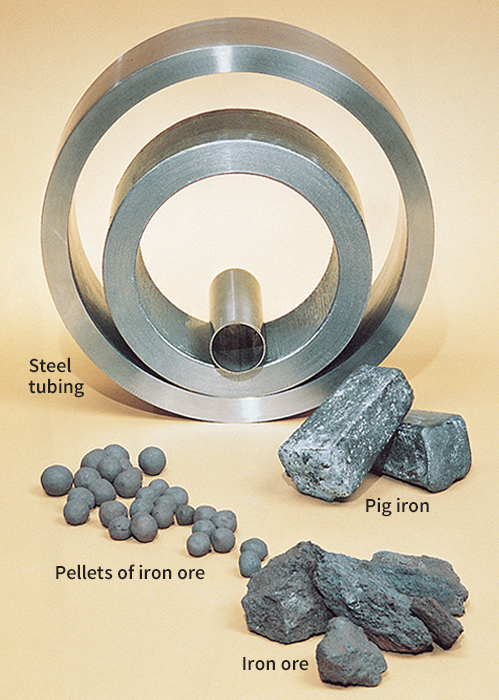

Iron is a silvery-white metal in its pure state. All plants, animals, and human beings need iron in their bodies. Iron is the most abundant element on Earth. The vast majority of iron is found in the planet’s core. Iron also is important because it is the basic material for many manufactured things. This metal seldom occurs in a pure state. It is obtained from certain kinds of rock, or ore (see Iron and steel (Sources of iron ore)).

Properties.

Iron can be identified by its physical qualities, or properties. It can be hammered into thin sheets or drawn out into fine wires. Iron is easily magnetized. It unites easily with nonmetals, such as sulfur, oxygen, and carbon. Iron unites easily with oxygen to form iron oxide, which we know as iron rust (see Oxidation; Rust). Iron may be alloyed (combined) with other metals. It is made into steel by adding a small amount of carbon (see Iron and steel (How steel is made)).

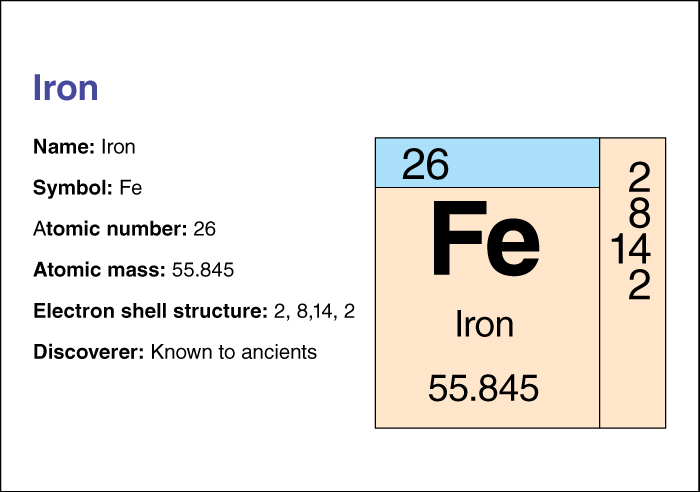

The chemical symbol for iron is Fe, which comes from the Latin word ferrum, meaning iron. Iron has an atomic number (number of protons in its nucleus) of 26. Its relative atomic mass is 55.845. An element’s relative atomic mass equals its mass (amount of matter) divided by 1/12 of the mass of carbon 12, the most abundant form of carbon. Iron has a density of 7.874 grams per cubic centimeter (see Density). Scientists also have set up a table to classify the hardness of minerals. In the hardness scale, iron is in Group V. This means the metal can be cut with a sharp knife, but only with great difficulty (see Hardness). Iron melts at 1535 °C and boils at roughly 2800 °C. It dissolves in water, but the process takes a long time. Chemists classify iron as a transition metal. For information on the position of iron on the periodic table, see the article Periodic table.

How bodies use iron.

General combinations of iron and protein are found in different parts of the body. Iron appears in the organs of the body where blood cells are formed and destroyed. Small amounts of iron are necessary in all cells of the body for their proper functioning. Iron is also needed in muscles and other tissues.

In most adult males, the total amount of iron in the body averages about 1/8 ounce (3.5 grams). About 65 percent of this iron is found in red blood cells, where it forms an essential part of a substance called hemoglobin. Hemoglobin carries oxygen from the lungs to other tissues of the body. It also carries carbon dioxide away from tissues to the lungs, which expel the carbon dioxide. Red blood cells live about 120 days. About 1 percent of all red blood cell iron is released daily from dead red cells. Almost all of the iron from dead red blood cells can be reused by the body. Daily loss of iron in a typical adult male is extremely small and principally results from the shedding of dead skin and from sweating. Iron loss is much higher in menstruating females and any other time that the body loses blood.

When a person’s daily diet does not provide a new supply of iron, eventually hemoglobin cannot be made. Over a period of time, the lack of sufficient iron will result in iron-deficiency anemia, a condition characterized by tiredness and weakness. About 0.1 percent of the body iron is in the blood plasma. This iron is bound to a protein called transferrin that transports it to cells or to the organs where the iron is stored. About 10 percent of the total body iron is in the muscles in the form of myoglobin. Myoglobin is slightly different in composition from hemoglobin, but its function is similar. It transports and stores oxygen for use during muscle contraction. See Blood; Hemoglobin.

The chief storage houses for iron in the body are the liver, the spleen, and bone marrow. These tissues store the iron that people and animals take into their bodies in the food they eat. Animal liver is the richest source of food iron. Foods of animal origin, particularly red meats, generally supply greater amounts of iron to the diet than do foods of plant origin. Exceptions are milk and dairy products, which are poor sources of dietary iron. After severe blood loss and during infancy, childhood, and pregnancy, the demands for iron are high, and the reserve supply may become low. In these situations, the diet must supply greater amounts of iron to the body.

In addition to carrying oxygen, iron also plays a part in the use of oxygen by tissues. Tissues use iron as part of enzymes to form a wide variety of essential bodily compounds. In plants, iron plays an important part in the formation of chlorophyll.

How iron is used in medicine.

Hundreds of years ago, the Hindus in India prepared a medicine known as Lauha Bhasma. They roasted sheets of iron, and then ground them into a fine white powder in oil or milk. This medicine was their treatment for anemia.

In 1831, scientists learned that too small an iron content in the diet caused a faulty formation of blood. Using iron scientifically to treat anemia began at that time. Since then, doctors have obtained added knowledge about the nature of the blood. But the only important use of iron in modern medicine is in the prevention and treatment of iron-deficiency anemias. See Anemia.

A great many preparations of iron are available in medicine. Most of these preparations are iron salts. Physicians prescribe iron compounds for treatment of iron-deficiency anemia and to prevent its occurrence during pregnancy and infancy. Most often these compounds are salts and are given in the form of pills or drops. Poisoning from medicines containing iron sometimes occurs among infants and children.