Jammu and Kashmir, << JUHM oo and KASH mihr or JUHM oo and kash MIHR, >> is a union territory in northern India. It lies between Pakistan and China in the Himalaya , the world’s tallest mountain system. About two-thirds of the people of Jammu and Kashmir are Muslims , making it the only state or territory in India with a Muslim majority. Srinagar , the largest city in Jammu and Kashmir, is the union territory’s summer capital. In the winter, the capital shifts south to Jammu, the second largest city.

The name Jammu and Kashmir—often shortened to simply Kashmir—refers both to the union territory of India and to a disputed region controlled partly by India, partly by Pakistan , and partly by China . The disputed region covers 85,806 square miles (222,236 square kilometers). The name Kashmir comes from the region’s most heavily populated area, which is also called Kashmir. This area includes the Vale of Kashmir, also called the Kashmir Valley, which lies in the Indian-held section. The historical region known as Kashmir includes the areas of Jammu and Ladakh, which also lie partly in the Indian-held section.

In 2019, India divided the land it claimed in Kashmir into two union territories—Jammu and Kashmir in the west, and Ladakh in the east. Previously, India had regarded the lands as a single state called Jammu and Kashmir. As union territories, the areas are controlled more directly by India’s federal government than they had been as a state. The areas within the Pakistani-held section are administered as Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. China controls a part of Kashmir called Aksai Chin.

India and Pakistan have been locked in conflict over the entire Kashmir region since 1947, when the two countries became independent. India claims all of Kashmir, including all of the Pakistani- and Chinese-held sections, and Pakistan claims all of Kashmir except the Chinese-held sections. The dispute has led to several wars and other outbreaks of violence between India and Pakistan.

Although India claims the entire Kashmir region, this article covers only the area under actual Indian control. Within that Indian-held region, the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir covers about 16,300 square miles (41,200 square kilometers) and has a 2011 census population of about 12.2 million. For more information about the Kashmir region as a whole, see Kashmir .

People

Population.

In general, Jammu and Kashmir can be divided into two cultural areas. Kashmir is in the northern part of the territory, and Jammu lies south of the Vale of Kashmir.

More than half of the people in Jammu and Kashmir live in the Kashmir area. The vast majority of people in this area are Muslims. Many of them practice a form of Islam known as Sufism , which includes some mystical practices and beliefs. The rest of the population lives in Jammu. This area has a Hindu majority and a Muslim minority. Both Kashmir and Jammu have small Sikh minorities.

Despite differences in religion, many of the people have a shared language and culture. The main language in the Kashmir area is Kashmiri. In Jammu, most people speak Dogri. The union territory’s official languages are Dogri, English, Hindi , Kashmiri, and Urdu . Other languages used include Gujjari and Pahari.

The Muslims and Hindus of Jammu and Kashmir have many common traditions. For example, Muslim and Hindu meals are similar. Muslims are forbidden by their religion from eating pork. Most Hindus also do not eat pork, even though their religion does not prohibit it. Similarly, Hindus are forbidden by their religion from eating beef, and Muslims also sometimes avoid beef. However, the eating of meat, usually lamb and mutton, is more common in Jammu and Kashmir and the northern states than in other parts of India. Even Kashmiri Hindus of the highest caste (social class)—the priests and scholars, called Brahmans or Pandits—regularly eat meat. Most Brahmans in other parts of India are vegetarians.

Muslims and Hindus in Jammu and Kashmir also have similar styles of dress. In the Kashmir region of the territory, both Hindu and Muslim men and women often wear a pheran, a long cloak made of wool or other fabric. In the winter, people often hold a small charcoal-burning stove, called a kangri, inside the pheran to keep warm.

Schools.

Free primary education is officially guaranteed in Jammu and Kashmir. However, ongoing violence in the region has caused the quality of education to suffer. Teachers are often reluctant to take jobs in schools in dangerous areas. The government has tried to address this problem by hiring villagers in these areas to teach local children. However, many of the villagers themselves have little education.

Jammu and Kashmir has two major universities—the University of Kashmir, in Srinagar, and the University of Jammu, in the city of Jammu. A university of agricultural sciences and technology also is based in Srinagar.

Land and climate

Land regions.

Jammu and Kashmir can be divided into two geographical regions, Jammu and Kashmir.

Jammu

lies in the southern part of the union territory, where the Punjab Plains and the Himalaya meet. The lowlands of southwestern Jammu are fairly fertile. North and east of the lowlands are the Siwalik hills. Because of soil erosion, only limited agriculture is possible in these hills. The hills give way to the Pir Panjal range, a wall of the Himalaya with many peaks rising more than 16,000 feet (4,880 meters) above sea level. Dense forests cover much of the lower Pir Panjal range.

Kashmir,

which includes the Vale of Kashmir, lies sandwiched between the Pir Panjal range and the Himalaya. The average altitude of the valley is about 5,000 feet (1,525 meters) above sea level. The bowllike valley may once have formed the basin of a huge ancient lake. It is Kashmir’s most densely populated and fertile region. Most of the valley is intensively farmed.

Rivers and lakes.

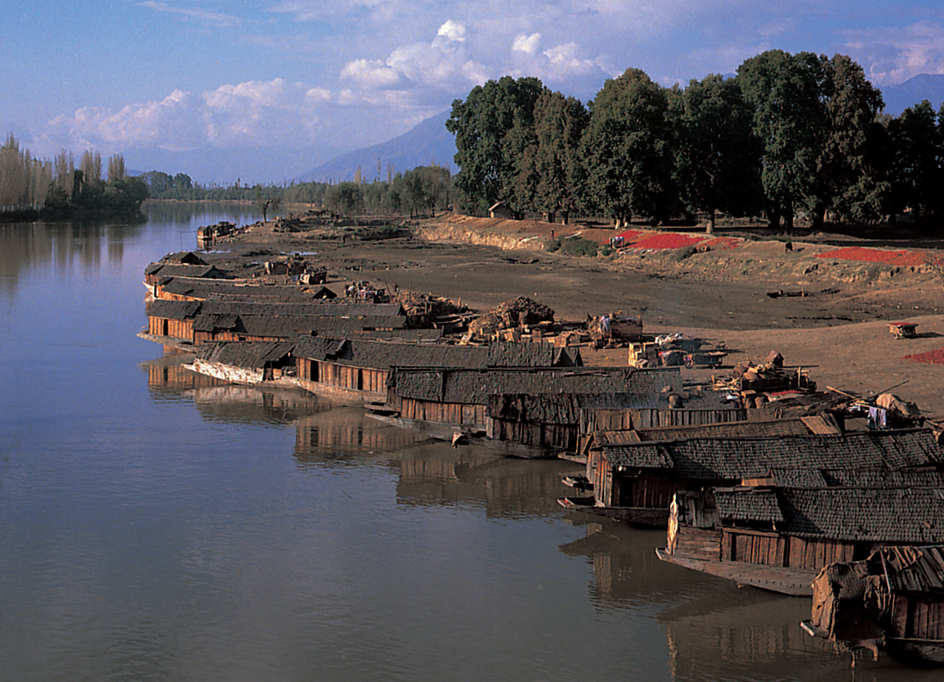

The Chenab River, an important river of the Punjab, flows for part of its course through Jammu. Several large freshwater lakes, notably the Dal and Wular lakes, dot the Vale of Kashmir. The Jhelum River flows through the vale and into and out of Wular Lake.

Plant and animal life.

In Jammu, the Himalayan foothills are heavily forested. Trees once grew in large areas of the Kashmir region, but much of the forestland has, over time, been cleared for human use. The chinar tree, a type of plane tree, is a well-known species of the Vale of Kashmir. Mulberry, horsechestnut, walnut, willow, and various pine trees also grow in the area. Vegetation is thin in the higher altitudes of the mountainous regions.

The territory is home to several rare species of wildlife. In some places, environmental damage, especially deforestation, has reduced the numbers of several species. Animals at risk of extinction in the vale include the snow leopard and a type of deer called the hangul or Kashmiri stag. Dachigam National Park, near Srinagar, provides a haven for these animals as well as many birds.

Climate.

Weather conditions vary sharply from region to region. Summer temperatures in Jammu can rise to 109 °F (43 °C). Kashmir, by contrast, has less extreme conditions. In Srinagar, the temperature usually ranges from 28 to 39 °F (–2 to 4 °C) in January, and from 64 to 88 °F (18 to 31 °C) in July.

Jammu and Kashmir receives less rainfall than many other parts of India. The mountains form a natural barrier against rain-bearing clouds from the Arabian Sea. In the city of Jammu, the average annual precipitation is about 44 inches (112 centimeters). In Srinagar, the average annual precipitation is about 28 inches (70 centimeters).

Economy

Agriculture

forms the backbone of the regional economy. Most people farm for a living. Until 1947, a few large landowners held most of the land in Jammu and Kashmir. India gained its independence that year. The National Conference Party took power in Jammu and Kashmir and launched an ambitious program of land reform. Farmland was spread among the peasants.

The vast majority of the people of Jammu and Kashmir make their living from agriculture, though much of the land cannot be cultivated. The richest farmland lies in southwestern Jammu and in the Vale of Kashmir. Many farms have been carved into the hillsides surrounding the vale. Most farms are only about 2 to 3 acres (0.8 to 1.2 hectares) in size.

Rice is the main crop. Barley, corn, millet, sorghum, wheat, and some vegetables are also grown. Most of these crops are grown for home consumption. Jammu and Kashmir also has many orchards that produce apples, cherries, oranges, peaches, and pears for export. The Vale of Kashmir is famous for its saffron, an orange-yellow dye and food flavoring that is extracted from the purple autumn crocus (see Saffron ).

Many farmers in Jammu and Kashmir raise livestock to supplement their income. Nomads of the Bakarwal and Gujjar ethnic groups raise buffaloes, cattle, and sheep, which they drive from high-altitude pastures in the summer to the plains in the winter. The Gujjars and some other mountain groups supplement their income from their herds by gathering medicinal herbs and morels (a mushroomlike fungus).

Manufacturing.

Small factories account for most of Jammu and Kashmir’s manufacturing output. Products include silk, carvings made from walnut wood, cricket bats and other sporting goods made from willow wood, and other handicrafts and processed agricultural goods. The region is especially famous for its beautiful rugs and shawls made from silk and pashmina (cashmere) wool. The government of Jammu and Kashmir has made efforts to attract information technology and electronics industries.

Mining

is not a significant commercial activity in the region. However, Jammu and Kashmir was once the most important sapphire-producing area in the world. The government has been trying to revive sapphire mining in the mountainous Doda district of Jammu. Some bauxite, coal, and gypsum are also found in the area.

Tourism

has traditionally been a major service industry in Jammu and Kashmir. But the industry has been hard-hit by the ongoing fighting in the region. Before 1990, hundreds of thousands of tourists visited Jammu and Kashmir, especially the scenic Vale of Kashmir, each year. But in 1990, rebels began fighting government forces, and the number of tourists dropped dramatically. Tourism began to revive only after 1996.

Energy sources.

Jammu and Kashmir has great potential to generate hydroelectric power because of the number of river systems that flow through it. The local government and the government of India have made considerable investments in building dams.

Transportation and communication.

Air and road links exist between the union territory’s major cities and the rest of India. However, bad winter weather often limits air services. The Kashmir and Jammu areas are connected to the rest of India by a single highway. Snow and landslides occasionally shut down the highway. The sole road between Kashmir and Ladakh closes for several months a year during the winter.

Loading the player...Boats on Dal Lake

Railroad passenger service connects Jammu with most major Indian cities. India is also investing in a railroad line that will run from the city of Jammu to Baramulla, a town north of Srinagar. The project is one of the most ambitious engineering projects in the world. Workers have to build dozens of tunnels and bridges at unusually high altitudes.

In 2005, bus services were launched between Srinagar and Muzaffarabad, a city in Pakistani-held Jammu and Kashmir. They were the first bus services in nearly 60 years between the Indian-held and Pakistani-held sections. Officials briefly suspended the bus service after an earthquake on Oct. 8, 2005, caused extensive damage to roads. In 2006, another bus service was launched between the Indian-held and Pakistani-held sections.

Jammu and Kashmir has many newspapers, published in Indian languages as well as English. Important English-language newspapers include The Daily Excelsior, The Kashmir Times, and Greater Kashmir. Doordarshan, the national television network, broadcasts throughout the area. Dozens of satellite-based television channels also serve the region.

Government

When Jammu and Kashmir became part of India, it acquired a special status that allowed it to have greater autonomy (self-government) than the other Indian states. Jammu and Kashmir was able to adopt its own constitution, though the Indian government directly controlled the state’s defense, foreign affairs, and communications. In 2019, India’s federal government cancelled the state’s special status and separate constitution. It made Jammu and Kashmir a union territory with a legislative assembly. Ladakh, which had been part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, became a separate union territory without a legislative assembly.

Executive.

Under the act that established the union territory, the president of India appoints a lieutenant governor for Jammu and Kashmir. The lieutenant governor appoints a chief minister, who presides over a Council of Ministers. The chief minister and Council of Ministers advise the lieutenant governor. Members of the council are appointed by the lieutenant governor on the advice of the chief minister.

Legislature.

According to the act Jammu and Kashmir is to have a one-house Legislative Assembly with members elected by the people. Officially, the assembly is to have 107 seats, with 24 of them kept vacant and reserved for the part of Kashmir that is claimed by India but controlled by Pakistan. Members are to serve 5-year terms, unless the lieutenant governor calls an earlier election.

Courts.

The highest court is called the High Court. Jammu and Kashmir shares the High Court with the union territory of Ladakh. Below this court are a number of district courts.

Local government.

Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir is divided into districts for purposes of local government. The districts are further divided into units called tehsils. Smaller units include towns, subdivisions, rural development blocks, and villages. In rural areas, councils called panchayats govern villages, blocks, and other local units. The current panchayat system was created in 1993. Because of violence by rebels opposed to Indian rule of Jammu and Kashmir, panchayat elections could not be held until 2001, when they began to take place in phases.

History

Early years.

The region that is now Jammu and Kashmir has been inhabited for thousands of years. Rock carvings found in neighboring Ladakh indicate that nomadic (wandering) tribes were in the region for a long period. These tribes included the Mons and the Dards.

Kashmir lies along a feeder route of the Silk Road , a group of ancient trade routes that connected China and Europe. Traders carried goods along the Silk Road from the 100’s B.C. to the A.D. 1500’s.

The Vale of Kashmir formed part of several Indian empires, including the empire of Ashoka in the 200’s B.C. An independent Hindu kingdom of Kashmir arose in this region around A.D. 620. It was ruled by the Karkota dynasty (family of rulers). About 855, another Hindu dynasty, the Utpalas, replaced the Karkotas. Avantivarman, the first Utpala king, ordered flood control and large-scale irrigation works in the Vale of Kashmir. These projects propelled the spread of agriculture in the region. The period of the Utpalas and the dynasties that followed, up to the 1300’s, was often dominated by power struggles among various groups.

Little is certain about the early history of Jammu. It may have come into existence around 900 as one of the hill states to the south of the Vale of Kashmir. This state was controlled by members of a Hindu warrior caste called Rajputs.

In the mid-1100’s, a writer named Kalhana composed a famous history of Kashmir called the Rajtarangini. The Rajtarangini is a chronicle of kings written in Sanskrit verse.

The spread of Islam.

By the early 1300’s, Muslim immigrants and teachers from central Asia began to move into the Vale of Kashmir, helping spread Islam there. In 1339, a Muslim soldier, Shah Mir, seized power. His dynasty spread Islam throughout the region. A later monarch in this dynasty, Zain-ul-Abidin, encouraged harmony between Hindus and Muslims and promoted science, arts, and culture. Zain-ul-Abidin reigned from 1420 to 1470.

The Mughal Empire , which ruled most of India in the 1500’s and 1600’s, took power in the areas of Kashmir and Jammu in the late 1500’s. Mughal rule of these areas lasted until the 1700’s, when the empire started to decline. As Mughal influence decreased, the Rajputs in Jammu regained power. Afghan invaders took control of Kashmir in the mid-1700’s. The Kashmiris suffered greatly under the brutal rule of the Afghans.

In the late 1700’s, Jammu began making tribute payments—that is, forced payments—to the Sikhs, who were gaining power in Punjab. In 1819, the Sikh emperor Ranjit Singh conquered Kashmir and made it part of his kingdom. In 1822, Ranjit Singh made Gulab Singh, a member of Jammu’s ruling class, the rajah (king) of Jammu. In the 1830’s, Gulab Singh’s military forces conquered Ladakh. Later, they extended their power to Baltistan and other regions north of the Vale of Kashmir.

The princely state.

In 1845 and 1846, British forces won a war against the Sikh empire in northern India. Gulab Singh stayed out of the war and helped arrange a peace agreement between the two sides. The British then granted him control of Kashmir for a payment of 7.5 million rupees. This action made Gulab Singh the maharajah (grand king) of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, which included the areas of Kashmir, Jammu, Ladakh, Baltistan, and Gilgit. Gulab Singh and his successors, all Hindus, were known as the Dogra dynasty. They ruled the Musim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir, subject to British supervision, until 1947.

As the Indian independence movement against the British grew in the 1920’s and 1930’s, a similar struggle began in Jammu and Kashmir against the monarchy. The most important leader of this movement was Sheik Mohammad Abdullah. He was allied with the leaders of the Indian National Congress, who wanted a united, democratic, and secular (nonreligious) India to replace British rule. However, Abdullah was opposed by leaders associated with the Muslim League . The Muslim League wanted a new country, Pakistan, to be created from the Muslim-majority regions of British India.

War and division.

In 1947, British India ceased to exist and was replaced by two new countries, India and Pakistan. The princely states, ruled by maharajahs, had to choose between joining India or Pakistan. However, the maharajah of Jammu and Kashmir, Hari Singh, delayed a decision on the status of his state. The issue became urgent after armed Muslim tribesmen from Pakistan invaded Jammu and Kashmir. These forces rapidly advanced to the outskirts of Srinagar. Forced to make a decision, Hari Singh chose to make Jammu and Kashmir part of India. He had the support of Abdullah, who believed his program of land reform would be opposed by the large landowners who dominated the Muslim League. Indian forces entered Jammu and Kashmir and began pushing back the Pakistani invaders, who had been joined by Pakistani troops.

The war between India and Pakistan continued until a cease-fire sponsored by the United Nations (UN) took effect on Jan. 1, 1949. The UN established a cease-fire line dividing Jammu and Kashmir (often called simply Kashmir) between the two countries. The UN also ordered that a plebiscite (vote of the people) be held to determine which country the people of Jammu and Kashmir wanted to join. But the plebiscite did not take place. Pakistan did not vacate the part of Kashmir it held, a precondition for the plebiscite. Also, India claimed that elections later held in the state substituted for a plebiscite.

In 1956, an elected assembly in Indian-held Kashmir agreed on a constitution that formally established the state of Jammu and Kashmir as a part of India. The state was given greater autonomy (self-government) than other states in India had. It governed the parts of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh contolled by India. India also considered the parts of Kashmir outside of its current control to be part of the state. Pakistan still wanted a plebiscite to determine Kashmir’s future.

By the late 1950’s, Chinese troops had begun moving into the Aksai Chin section of eastern Ladakh. China secured control of Aksai Chin after a brief war with India in 1962. In 1963, Pakistan handed over additional territory in Kashmir to China.

In 1965, Pakistan invaded Indian-held Kashmir, but the war produced no territorial gains for Pakistan. In 1971, India and Pakistan again went to war in Kashmir, after India backed a rebellion in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The Shimla Agreement of 1972, which settled the conflict, established a border called the Line of Control between the Indian-held and Pakistani-held parts of Kashmir. But the line stopped short of the Siachen Glacier, northwest of Aksai Chin. India and Pakistan have continued to fight over this area.

Rebellion and unrest.

In the late 1980’s, a number of protests were held in the Vale of Kashmir, in Indian-controlled territory. Some protesters wanted Kashmir to join Pakistan, and others wanted independence for Kashmir. By 1990, the protests had developed into armed combat between guerrillas and Indian security forces. Since then, probably more than 40,000 people have died in the fighting. Several rebel groups, some operating from bases in Pakistan, continue to battle Indian forces. Most of the rebels belong to radical Muslim groups.

International concern over the India-Pakistan conflict rose sharply in 1998, after both countries tested nuclear weapons. In 1999, fighting broke out between India and Pakistan after Pakistani troops occupied the Kargil region on the Indian side of the Line of Control.

In December 2001, terrorists attacked India’s Parliament building in New Delhi and killed several people. India blamed Pakistan for supporting the terrorists, a claim that Pakistan denied. The incident brought the two countries to the brink of war. India built up forces along the Line of Control and elsewhere along the border between the two countries, and Pakistan responded in kind. Tensions increased in May 2002, after an attack by militants on an Indian army base in Jammu. Later in 2002, international diplomacy eased the tensions, and in October, both countries announced they would pull back troops. India and Pakistan have attempted to work toward a peaceful solution to the Kashmir conflict.

Recent developments.

In October 2005, a major earthquake hit north of the city of Islamabad in Pakistan. More than 73,000 people were killed in northern Pakistan and Pakistani-held Kashmir, and at least 1,300 were killed in Indian-held Kashmir. Over 3 million people were left homeless throughout the region. Later that year, Indian and Pakistani officials opened the border in five places between Indian-held and Pakistani-held Kashmir to ease the flow of aid.

In August 2019, the federal government of India revoked the special constitutional status that had given the state of Jammu and Kashmir more authority over its own affairs than the other states in India had. Ending Jammu and Kashmir’s special status had long been a goal of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which had recently won a resounding victory in the nation’s general elections.

The BJP-dominated Parliament then passed a bill to divide Jammu and Kashmir into two parts. The legislation made the western part of the state into a union territory called Jammu and Kashmir. Ladakh, in the east, became a separate union territory. India’s federal government exercises more direct authority in union territories than it does in states, so this action further reduced local control.

See also Bharatiya Janata Party ; India, History of ; Kashmir ; Pakistan (History) ; Srinagar .