Japan is an island country in the North Pacific Ocean. It lies off the east coast of mainland Asia across from Russia, Korea, and China. Four large islands and thousands of smaller ones make up Japan. The four major islands—Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyushu, and Shikoku—form a curve that extends for about 1,200 miles (1,900 kilometers). About 125 million people are crowded on these islands, making Japan one of the most densely populated countries in the world.

The Japanese call their country Nippon or Nihon, which means source of the sun. The name Japan may have come from Zipangu, the Italian name given to the country by Marco Polo, a Venetian traveler of the late 1200’s. Polo had heard of the Japanese islands while traveling through China.

Mountains and hills cover most of Japan, making it a country of great beauty. But the mountains and hills take up so much area that the great majority of the people live on a small portion of the land—narrow plains along the coasts. These coastal plains have much of Japan’s best farmland and most of the country’s major cities. Most of the people live in urban areas. Japan’s big cities are busy, modern centers of culture, commerce, and industry. Tokyo is the capital and largest city.

Japan is one of the world’s economic giants. Its total economic output is one of the largest in the world. The Japanese manufacture a wide variety of products, including automobiles, computers, steel, television sets, and textiles. The country’s factories have some of the most advanced equipment in the world. Japan has become a major economic power even though it has few natural resources. Japan imports many of the raw materials needed for industry and exports finished manufactured goods.

Life in Japan reflects the culture of both the East and the West. For example, the favorite sporting events in the country are baseball games and exhibitions of sumo, an ancient Japanese style of wrestling. Although most Japanese wear Western-style clothing, many women dress in the traditional kimono for festivals and other special occasions. The Japanese noh and kabuki dramas, both hundreds of years old, remain popular. But the Japanese people also flock to see motion pictures and rock music groups. Many Japanese artworks combine traditional and Western styles and themes.

Early Japan was greatly influenced by the neighboring Chinese civilization. From the late 400’s to the early 800’s, the Japanese borrowed heavily from Chinese art, government, language, religion, and technology. During the mid-1500’s, the first Europeans arrived in Japan. Trade began with several European countries, and Christian missionaries from Europe converted some Japanese. During the early 1600’s, however, the rulers of Japan decided to cut the country’s ties with the rest of the world. They wanted to keep Japan free from outside influences.

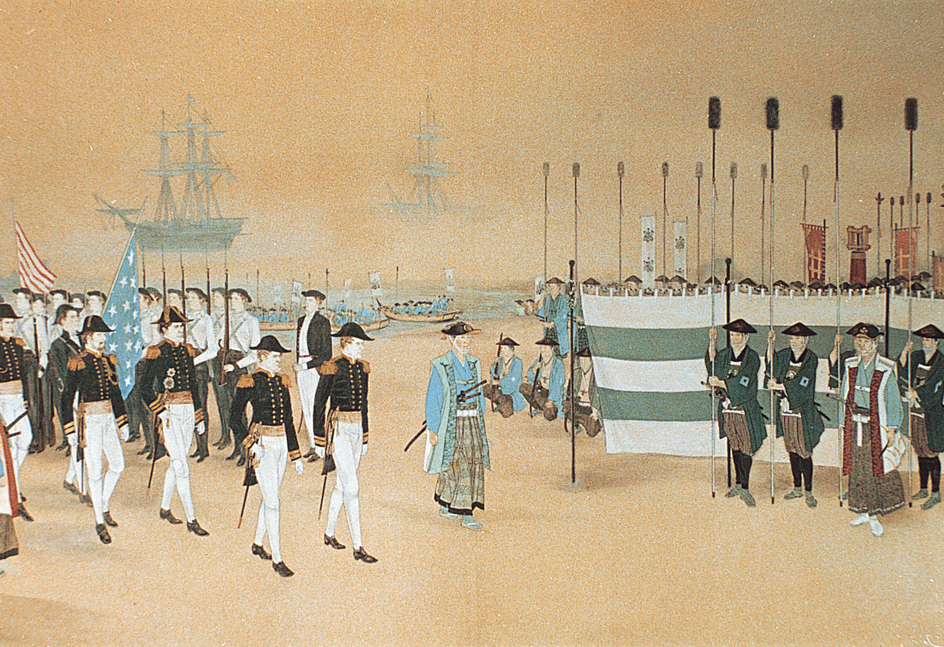

Japan’s isolation lasted until 1853, when Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the United States sailed his warships into Tokyo Bay. As a result of Perry’s show of force, Japan agreed in 1854 to open two ports to U.S. trade.

During the 1870’s, the Japanese government began a major drive to modernize the country. New ideas and manufacturing methods were imported from Western countries. By the early 1900’s, Japan had become an industrial and military power.

During the 1930’s, Japan’s military leaders gained control of the government. They set Japan on a program of conquest. On Dec. 7, 1941, Japan attacked United States military bases at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, bringing the United States into World War II. The Japanese won many early victories, but then the tide turned in favor of the United States and the other Allied nations. In August 1945, U.S. planes dropped the first atomic bombs used in warfare on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On Sept. 2, 1945, Japan officially surrendered, and World War II ended. Loading the player...

Eyewitness account of the bombing of Nagasaki

World War II left Japan completely defeated. Many Japanese cities lay in ruins, industries were shattered, and Allied forces occupied the country. But the Japanese people worked hard to overcome the effects of the war. By the 1970’s, Japan had become a great industrial nation. The success of the Japanese economy attracted attention throughout the world. Today, few nations enjoy a standard of living as high as Japan’s.

Government

Japan is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary government. The Constitution, which took effect in 1947, guarantees many rights to the people, including freedom of religion, speech, and the press. It establishes three branches of government—the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. All men and women age 18 and older are allowed to vote.

Japan's national anthem

National government.

Japan’s emperor is considered a symbol of the nation. The emperor performs some ceremonial duties specified in the Constitution, but he does not possess any real power to govern. The emperor inherits his throne.

The Diet is the national legislature, the highest lawmaking body of Japan. The Diet consists of two houses, the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors. The representatives have slightly more power under the Constitution than the councillors do.

The House of Representatives has 465 members who are elected to serve terms of up to four years. Voters directly elect a majority of the representatives. The remainder are chosen under a system called proportional representation, which gives a political party a share of seats in the Diet according to its share of the total votes cast.

The House of Councillors has 248 members. Most councillors are elected by the people of electoral districts, and the rest are elected through proportional representation. Councillors serve six-year terms.

The prime minister is the head of the executive branch of the government. The prime minister leads the government and represents Japan abroad. Members of the Diet elect the prime minister, who must be a civilian and an elected member of the Diet. The prime minister selects members of the Cabinet to help govern the country. At least half the Cabinet ministers must be members of the Diet.

Local government.

Japan is divided into 47 political units called prefectures. The residents of each prefecture elect a governor and representatives to a prefectural legislative assembly. The residents of each city, town, and village also elect a mayor and a local council.

Politics.

The Liberal Democratic Party is the largest political party in Japan. Other important parties include the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, the Democratic Party of the People, the Japanese Communist Party, the Japan Innovation Party, and Komeito.

Courts.

The Supreme Court is the nation’s highest court. It consists of 1 chief justice and 14 associate justices. The Cabinet names, and the emperor appoints, the chief justice. The Cabinet appoints the associate justices. Every 10 years, the people have an opportunity to remove a justice from the court by voting in a referendum.

The Supreme Court oversees the training of Japan’s judges and attorneys. It also administers the national system of courts. The court system includes 8 regional high courts; 50 district courts; 50 family courts, which handle domestic cases; and hundreds of summary courts, which handle minor offenses and small claims without the formal procedures of other courts.

Armed forces.

The Constitution prohibits Japan from maintaining military forces to wage war. But Japan does have a Ministry of Defense to preserve Japan’s peace, independence, and national security, and to aid the country’s allies in foreign conflicts. A civilian member of the Cabinet heads the ministry. The ministry oversees an army, a navy, and an air force. All service is voluntary.

People

Japan is one of the world’s most populous nations. About 90 percent of the people live on the coastal plains, which make up only about 20 percent of Japan’s territory. These plains rank among the most thickly populated places in the world. Millions of people crowd the big cities along the coasts, including Tokyo, Japan’s capital and largest city. The Tokyo metropolitan region, which includes the cities of Yokohama and Kawasaki, is the most populous urban area in the world.

Ancestry.

The Japanese are descended from peoples who migrated to the islands from other parts of Asia. Many of these peoples came in waves from the northeastern part of the Asian mainland, passing through the Korean Peninsula. Some ancestors of the Japanese may have come from islands south of Japan.

Historians do not know for certain when people first arrived in Japan. But by about 10,000 B.C., the Japanese islands were inhabited by people who hunted, fished, and gathered fruits and plants for food. This early culture is known as the Jomon, which means cord-marked, because the people made pottery that was covered with the impressions of ropes or cords.

About 300 B.C., a new, settled agricultural society began to replace the Jomon. This culture is called the Yayoi, after the section of modern Tokyo where remains of the culture were found. The Yayoi people grew rice in irrigated fields and established villages. They cast bronze into bells, mirrors, and weapons. The Japanese people of today are probably descended from the Yayoi. In fact, scholars believe that by A.D. 100 the people living throughout the islands closely resembled the present-day Japanese in language and appearance.

Japan’s population consists almost entirely of ethnic Japanese. Koreans, Chinese, and Brazilians make up Japan’s largest ethnic minority groups. Another minority group is the Ainu << EYE noo >> . Most of the Ainu live on Hokkaido, the northernmost of Japan’s main islands. Many Ainu have intermarried with the Japanese and adopted the Japanese culture. The rest of the Ainu are ethnically and culturally different from the Japanese. Some scholars believe the Ainu were Japan’s original inhabitants, who were pushed northward by the ancestors of the present-day Japanese people.

Japan’s minority groups suffer from prejudice. But the people who have suffered the most injustices are a group of Japanese known as the burakumin. The burakumin make up about 2 percent of Japan’s population. They came from buraku (villages) traditionally associated with such tasks as the execution of criminals, the slaughter of cattle, and the tanning of leather. According to Japanese religious traditions, these tasks and the people who performed them were considered unclean. As a result, the burakumin—though not ethnically different from other Japanese—have long been discriminated against. Many of the burakumin live in segregated urban slums or special villages. The burakumin have started an active social movement to achieve fair treatment, but they have had only limited success so far.

Language.

Japanese is the official language of Japan. Spoken Japanese has many local dialects. These local dialects differ greatly in pronunciation. However, the Tokyo dialect is the standard form of spoken Japanese. Almost all the people understand the Tokyo dialect, which is used in schools and on radio and television. Many Japanese can also speak English to some extent. A number of Japanese words, such as aisu kuriimu (ice cream) and guruupu (group), are based on English.

Written Japanese is considered one of the most difficult writing systems in the world. It uses Japanese phonetic symbols that represent sounds as well as Chinese characters. Each character is a symbol that stands for a complete word or syllable. Schools in Japan also teach students to write the Japanese language with the letters of the Roman alphabet.

Way of life

City life.

About 92 percent of the Japanese people live in urban areas. Most of the urban population is concentrated in three major metropolitan areas: (1) the Tokyo metropolitan region, which also includes the cities of Kawasaki and Yokohama; (2) Osaka; and (3) Nagoya.

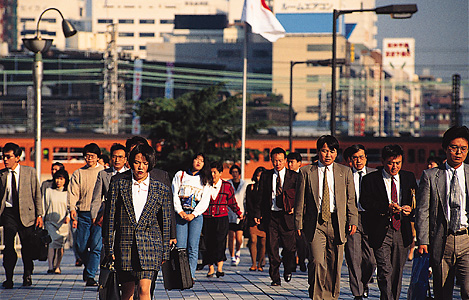

The prosperity of Japanese society is visible in these cities. The downtown streets are filled with expensive, late-model automobiles and are lined with glittering high-rise buildings. The buildings house expensive apartments, prosperous firms, fashionable department stores, and elegant shops.

Most Japanese people who live in cities and suburbs enjoy a high standard of living. Many work in banks, hotels, offices, and stores. Others hold professional or government jobs.

Housing in metropolitan areas includes modern high-rise apartments and traditional Japanese houses. The houses are small because land prices are extremely high. Tokyo, for example, has some of the most expensive land in the world.

In traditional homes, the rooms are separated by sliding paper screens, which can be rearranged as needed. Straw mats called tatami cover the floors. People sit on cushions and sleep on a type of padded quilt called a futon. Today, many Japanese apartments and houses have one or more rooms fitted with carpets instead of tatami and containing Western-style chairs and tables.

Japan’s big cities, like those in many other countries, face such problems as overcrowding and air and water pollution. However, crime and poverty are not as common in Japan as they are in most Western nations.

Rural life.

Only about 8 percent of the Japanese people live in rural areas. Farm families make up most of the rural population. In rural areas along the coasts, some Japanese make their living by fishing and harvesting edible seaweed.

Most families in rural areas live in traditional Japanese-style wooden houses like those in the cities. Housing is cheaper in the countryside than in cities, but it is still expensive by international standards.

Japan’s rural areas face an uncertain future. Only about 15 percent of farm households live on their farming incomes alone. By taking second and third jobs, farmworkers maintain an average household income slightly higher than that of urban workers. But rural populations have declined as the children of farmers leave to work in Japan’s cities.

Clothing.

Some well-to-do Japanese buy designer-made garments, but the majority of the people purchase more moderately priced clothing. The styles they buy are similar to those worn in the United States and Western Europe.

For business and professional men, typical workday wear consists of a dark suit, white shirt, conservative tie, black shoes, and a dark woolen overcoat for winter. Younger men sometimes wear patterned sport coats and colorful ties. When not at work, Japanese men typically wear slacks and a casual shirt or sweater.

Most working women wear a skirt, blouse, and jacket to the office. Most women who do not work outside the home dress in moderately priced dresses or blouses with skirts or slacks when at home or in their own neighborhood. While in a major city shopping area or business district, many of these women wear expensive imported dresses or skirts, blouses, and jackets. For accessories, they wear fine jewelry and silk scarves.

On special occasions, such as weddings, funerals, or New Year’s celebrations, Japanese women may dress in the traditional long garment called a kimono. A kimono is tied around the waist with a sash called an obi and worn with sandals known as zori.

Most Japanese children wear uniforms to school. The uniforms often consist of a black or navy jacket worn with matching shorts, skirt, or slacks. On weekends, Japanese children dress in the latest casual styles from Europe and the United States or in T-shirts printed with Japanese cartoon characters.

Food and drink.

Many Japanese families eat at restaurants on weeknights and weekends as well as on special occasions. Favorite dining spots include Japan’s new casual family restaurants. Roads and superhighways are lined with such American establishments as Denny’s and McDonald’s and similar Japanese-owned chains called Skylark and Lotteria.

When dining at home, most older people eat traditional Japanese foods. They drink tea and eat rice at almost every meal. They supplement the rice with fish, tofu (soybean curd cake), pickled vegetables, soups made with miso (soybean paste), and on occasion, eggs or meat.

Younger people eat fewer of the traditional foods. Like their elders, they eat fish, but they also like to eat beef, chicken, and pork. They eat more fruit, including imported kiwi and grapefruit as well as the apples, oranges, pears, and strawberries grown in Japan. They also consume larger amounts of eggs, cheese, and milk than their parents. Instead of rice, many prefer bread, doughnuts, and toast. In fact, by 1990, total rice consumption in Japan had dropped to about half its level in 1960.

Overall, younger people now take in significantly more protein and fat than their grandparents did. The nutritional change has helped make the members of the younger generation an average of 3 to 4 inches (8 to 10 centimeters) taller than their grandparents.

Recreation.

Japanese people are energetic sports enthusiasts. Schools encourage children to enjoy sports, and adults spend large sums on athletic equipment and membership fees. Baseball, bowling, golf, gymnastics, and tennis attract large numbers of participants, and many Japanese are good swimmers and runners. Another popular sport is kendo, a Japanese form of fencing in which bamboo or wooden sticks are used for swords. Many Japanese also practice aikido, judo, and karate, traditional martial arts that involve fighting without weapons. Spectator events, such as baseball, horse racing, soccer, and the Japanese form of wrestling called sumo, are also popular.

Hobbies are another important leisure time activity for Japanese men and women. Popular hobbies include performing the tea-serving ceremony, chanting medieval ballads, or ikebana (flower arranging). Many Japanese study with masters of these arts to improve their skills.

Travel is a favorite leisure pursuit. Every year, millions of Japanese visit foreign countries. Within Japan, popular travel destinations include temples or shrines, hot springs, and famous historical sites.

Other leisure pursuits common in Japan include watching television, playing video games, and listening to recorded music. The Japanese also like to read books and magazines. Many workers read during the hours spent commuting by train between homes in the suburbs and jobs in the city.

Men in Japan often spend their free time after work socializing in small groups. They stop off at little shops, restaurants, and bars to have a snack together and a drink of sake (Japanese-style rice wine) or beer.

The Japanese celebrate many festivals during the year. One of the most popular celebrations in Japan is the New Year’s Festival, which begins on January 1 and ends on January 3. During the festival, the Japanese dress up, visit their friends and relatives, enjoy feasts, and exchange gifts.

Religion.

Many Japanese people say they are not devout worshipers and do not have strong religious beliefs. However, nearly everyone in Japanese society engages in some religious practices or rituals. Those practices are based on the two major religious traditions in Japan, Shinto and Buddhism.

Shinto means the way of the gods. It is the native religion of Japan and dates from prehistoric times. Shintoists worship many gods, called kami, that are found in mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, and other parts of nature. Shinto also involves ancestor worship.

In 1868, the Japanese government established an official religion called State Shinto. State Shinto stressed patriotism and the worship of the emperor as a divine being. The government abolished State Shinto after World War II, and the emperor declared he was not divine.

Today, fewer than 3 percent of Japanese practice strict traditional Shinto. But almost all Japanese perform some Shinto rituals. Many people visit Shinto shrines to make offerings of fruit, rice, prayers, and other gifts to the gods. In return, they may ask the gods for favors, such as the safe birth of a child, success on examinations, or good health. Japanese people typically invite Shinto priests to preside at weddings and to offer blessings for the New Year or for the construction of new buildings.

Buddhism came to Japan from India via China in the 500’s. Buddhism has a more elaborate set of beliefs than Shinto, and it offers a more complicated view of humanity, the gods, and life and death. Generally, Buddhists believe that a person can obtain perfect peace and happiness by leading a life of virtue and wisdom. Buddhism stresses the unimportance of worldly things. Many Japanese turn to Buddhist priests to preside at funerals and other occasions when they commemorate the dead.

A variety of religious groups called New Religions developed in Japan during the 1800’s and 1900’s. Many of these religions combine elements of Buddhism, Shinto, and in some cases, Christianity. Japan also has a small number of Christians.

Gender roles.

Japanese society imposes strong expectations on women and men. The society expects women to marry in their mid-20’s, become mothers soon afterward, and stay at home to attend to the needs of their husband and children. Women often have a dominant role in raising children and handling the family finances. Men are expected to support their families as sole breadwinners. To make this possible, Japanese employers provide male workers with family allowances.

Most Japanese men accept this idea of their place in society, and many women do, too. But in practice, the majority of Japanese women do hold jobs at one time or another. Most women work before they marry, and many of them return to the labor force after their children are in school or grown. In addition, some Japanese women work while their children are young.

Altogether, about 50 percent of all Japanese women over age 15 are in the labor force at any one time. But because of the society’s expectations about gender roles, female employees earn lower incomes and receive fewer benefits than male employees do, and have almost no job security.

The traditional ideas about gender roles have begun to change in Japan, most quickly among younger women. Many women in their early 20’s are reluctant to give up their jobs and income. As a sign of that change, an increasing number of Japanese women are postponing marriage until they are in their late 20’s or early 30’s.

Education.

Japanese society places an extremely high value on educational achievement, particularly for males. The Japanese measure educational achievement chiefly by the reputation of the university a student attends. The student’s grades or field of study are less important as signs of success. Under most circumstances, any student who graduates from a top-ranked university has a big advantage over other college graduates in seeking employment. Families work hard to get their children into a good university, starting as soon as the youngsters begin school.

After six years at an elementary school, almost all Japanese children continue for another three years at a junior high school. Education at public schools is free during these nine years for children 6 to 14 years of age.

Japanese elementary and junior high school students study such subjects as art, homemaking, the Japanese language, mathematics, moral education, music, physical education, science, and social studies. In addition, many junior high school students study English or another foreign language. Students spend much time learning to read and write Japanese because the language is quite difficult. The country has an exceptionally high literacy rate, however. Almost all adults can read and write.

Public school students attend classes Monday through Friday and half a day on Saturday, except for two weeks each month when they have Saturdays off. The Japanese school year runs from April through March of the next year. Vacation is from late July through August.

During the last two years of junior high school, many students focus on attaining admission to a high school with a good record of getting its graduates into top universities. Many of the most successful high schools are expensive private institutions that require incoming students to pass a difficult entrance examination. To prepare for the test, many eighth- and ninth-grade students spend several hours each day after school taking exam-preparation classes at private academies called juku.

Students attend senior high school for three years. Classes include many of the same subjects studied in junior high school, along with courses to prepare students for college or train them for jobs. While in high school, a student may continue to study at a juku as preparation for the entrance exam to a university.

Japan has more than 500 universities and about 600 technical and junior colleges. The most admired institutions are the oldest national universities, the University of Tokyo and Kyoto University. Two private universities, Keio University and Waseda University in Tokyo, are also highly regarded.

After students are admitted to one of these four universities, they tend to pay more attention to extracurricular activities than to their classwork. Simply being at a top university will ensure job interviews at the country’s best firms.

Because Japanese society does not expect a woman to be the family’s main wage earner, the educational experience for girls is more limited. About half of the women who get college educations attend technical or junior colleges rather than universities. In contrast, nearly all men who get a college degree attend universities. At the graduate level, male students outnumber females 2 to 1.

Japanese students consistently score well on international tests of science and mathematics skills. But many Japanese are concerned about the disadvantages of their educational system. Parents feel that it places too much emphasis on memorization and taking exams. Most would prefer to have their children educated in a more creative environment that requires less time in classrooms. Many Japanese politicians and business people agree that their educational system has flaws.

The arts

For hundreds of years, Chinese arts had a great influence on Japanese arts. A Western influence began about 1870. However, there has always been a distinctive Japanese quality about the country’s art.

Music.

Most forms of Japanese music feature one instrument or voice or a group of instruments that follow the same melodic line instead of blending in harmony. Japanese instruments include the lutelike biwa; the zitherlike koto; and the three-stringed banjolike samisen, or shamisen. Traditional music also features drums, flutes, and gongs. Performances of traditional music draw large crowds in Japan. Most types of Western music are also popular. Many Japanese cities have their own professional symphony orchestras that specialize in Western music. Loading the player...

Japanese taiko drumming

Theater.

The oldest form of traditional Japanese drama is the noh play, which developed during the 1300’s. Noh plays are serious treatments of history and legend. Masked actors perform the story with carefully controlled gestures and movements. A chorus chants most of the important lines in the play.

Two other forms of traditional Japanese drama—bunraku (puppet theater) and the kabuki play—developed during the late 1600’s. In puppet theater, a narrator recites the story, which is acted out by large, lifelike puppets. The puppet handlers work silently on the stage in view of the audience. Kabuki plays are melodramatic representations of historical or domestic events. Kabuki features colorful costumes and makeup, spectacular scenery, and a lively and exaggerated acting style.

The traditional types of theater remain popular in Japan. But the people also enjoy new dramas by Japanese playwrights, as well as Western plays.

Literature.

Japan has a rich literary heritage. Much of the country’s literature deals with the fleeting quality of human life and the never-ending flow of time. Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting to the empress, wrote The Tale of Genji during the early 1000’s. This long novel is generally considered the greatest work of Japanese fiction and possibly the world’s first novel.

Sculpture.

Some of the earliest Japanese sculptures were haniwa, small clay figures made from the A.D. 200’s to 500’s. Haniwa were placed in the burial mounds of important Japanese people. The figures represented animals, servants, warriors, weapons, and objects of everyday use.

Japanese sculptors created some of their finest works for Buddhist temples. The sculptors worked chiefly with wood, but they also used clay and bronze. The most famous bronze statue in Japan, the Great Buddha at Kamakura, was cast during the 1200’s.

Painting.

Early Japanese painting dealt with Buddhist subjects, using compositions and techniques from China. From the late 1100’s to the early 1300’s, many Japanese artists painted long picture scrolls. These scrolls realistically portrayed historical tales, legends, and other stories in a series of pictures. Ink painting flourished in Japan from the early 1300’s to the mid-1500’s. Many of these paintings featured black brushstrokes on a white background.

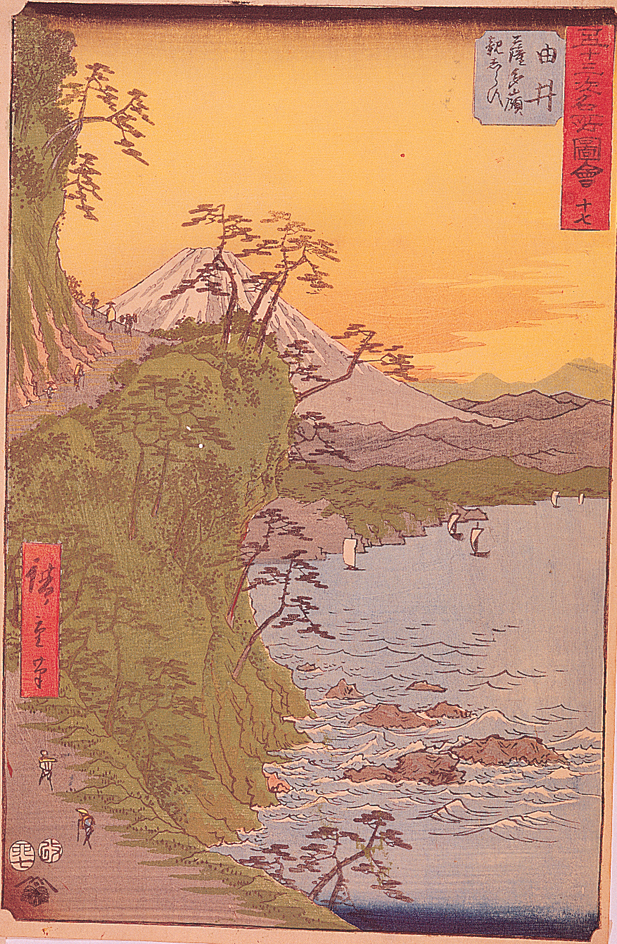

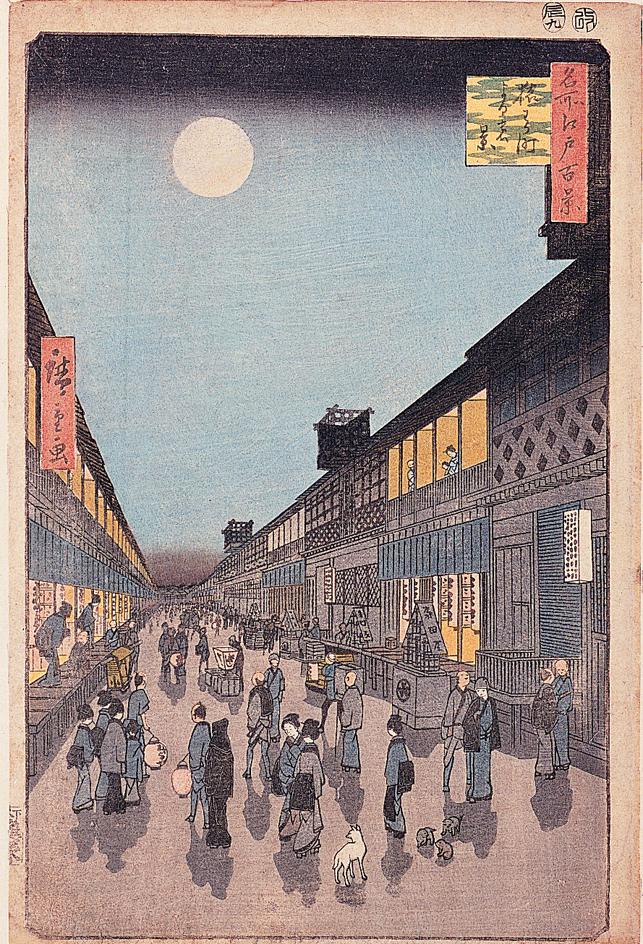

During the mid-1500’s and early 1600’s, a decorative style of painting developed in Japan. Artists used bright colors and elaborate designs and added gold leaf to their paintings. From the 1600’s to the late 1800’s, artists created colorful wood-block prints. Printmaking is still popular in Japan.

Architecture.

Many architectural monuments in Japan are Buddhist temples. These temples have large tile roofs with extending edges that curve gracefully upward. Traditional Shinto shrines are wooden frame structures noted for their graceful lines and sense of proportion. The simple style of Shinto architecture has influenced the design of many modern buildings in Japan. Japanese architecture emphasizes harmony between buildings and the natural beauty around them. Landscape gardening is a highly developed art in Japan.

Other arts.

Japan ranks among the world’s leading producers of motion pictures. Many Japanese films have earned international praise. The Japanese have long been famous for their ceramics, ivory carving, lacquerware, and silk weaving and embroidery. Other traditional arts include flower arranging, cloisonne (a type of decorative enameling), and origami (the art of folding paper into decorative objects).

The land

Japan is a land of great natural beauty. Mountains and hills cover about 70 percent of the country. In fact, the Japanese islands consist of the rugged upper part of a great mountain range that rises from the floor of the North Pacific Ocean. Jagged peaks, rocky gorges, and thundering mountain waterfalls provide some of the country’s most spectacular scenery. Thick forests thrive on the mountainsides, adding to the scenic beauty of the Japanese islands.

Loading the player...Japan: Land of contrast

Japan lies on an extremely unstable part of the earth’s crust. As a result, the land is constantly shifting. This shifting causes two of Japan’s most striking natural features—earthquakes and volcanoes. The Japanese islands have about 1,500 earthquakes a year. Most of them are minor tremors that cause little damage, but severe earthquakes occur every few years. Undersea quakes sometimes cause a series of huge, destructive waves called a tsunami along Japan’s Pacific coast. The Japanese islands have more than 150 major volcanoes. Over 60 of these volcanoes are active.

Numerous short, swift rivers cross Japan’s rugged surface. Most of the rivers are too shallow and steep to be navigated. But their waters are used to irrigate farmland, and their rapids and falls supply power for hydroelectric plants. Many lakes nestle among the Japanese mountains. Some lie in the craters of extinct volcanoes. A large number of hot springs gush from the ground throughout the country.

The four main Japanese islands, in order of size, are Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku. Thousands of smaller islands and islets lie near these major islands. Japan’s territory also includes the Ryukyu and Bonin island chains.

Japan’s four chief islands have 4,628 miles (7,448 kilometers) of coastline. The Pacific Ocean lies to the east and south of Japan. The Sea of Japan washes the country’s west coast. It is sometimes called the East Sea because it lies east of Russia and the Korean peninsula.

Honshu,

Japan’s largest island, has an area of 89,240 square miles (231,132 square kilometers). About 80 percent of the Japanese people live on Honshu.

Three mountain ranges run parallel through northern Honshu. Most of the people in this area live in small mountain valleys. Agriculture is the chief occupation. East of the ranges, along the Pacific, lies the Sendai Plain. West of the mountains, the Echigo Plain extends to the Sea of Japan.

The towering peaks of the Japanese Alps, the country’s highest mountains, rise in central Honshu. Southeast of these mountains lies a chain of volcanoes. Japan’s tallest and most famous peak, Mount Fuji, or Fujiyama, is one of these volcanoes. Mount Fuji, which is inactive, rises 12,388 feet (3,776 meters) above sea level. The Kanto Plain, the country’s largest lowland, spreads east from the Japanese Alps to the Pacific. This lowland is an important center of agriculture and industry. Tokyo sprawls over the southern part of the Kanto Plain. Two other major agricultural and industrial lowlands—the Nobi Plain and Osaka Plain—lie south and west of the Kanto region.

Most of southwestern Honshu consists of rugged, mountainous land. Farming and fishing villages and some industrial cities lie on small lowlands scattered throughout this region.

Hokkaido,

the northernmost of Japan’s four major islands, covers 30,144 square miles (78,073 square kilometers). It is the country’s second largest island but has only about 4 percent of Japan’s total population. Much of the island consists of forested mountains and hills. A hilly, curved peninsula extends from southwestern Hokkaido. Northeast of this peninsula is the Ishikari Plain, Hokkaido’s largest lowland and chief agricultural region. Smaller plains border the island’s east coast. The economy of Hokkaido depends mainly on dairy farming, fishing, and forestry. The island is also a popular recreational area. Long winters and heavy snowfall make Hokkaido ideal for winter sports.

Kyushu,

the southernmost of the main islands, occupies 14,114 square miles (36,554 square kilometers). After Honshu, Kyushu is Japan’s most heavily populated island, with about 10 percent of the population. A chain of steep-walled, heavily forested mountains runs down the center of the island. Northwestern Kyushu consists of rolling hills and wide plains. Many cities are found in this heavily industrialized area. Kyushu’s largest plain and chief farming district is located along the west coast.

The northeastern and southern sections of Kyushu have many volcanoes, high lava plateaus, and large deposits of volcanic ash. In both regions, only small patches of land along the coasts and inland can be farmed. Farmers grow some crops on level strips of land cut out from the steep sides of the lava plateaus.

Shikoku,

the smallest of the main Japanese islands, covers 7,049 square miles (18,256 square kilometers). About 3 percent of the Japanese people live on the island. Shikoku has no large lowlands. Mountains cross the island from east to west. Most of the people live in northern Shikoku, where the land slopes downward to the Inland Sea. Hundreds of hilly, wooded islands dot this beautiful body of water. Farmers grow rice and a variety of fruits on the fertile land along the Inland Sea. Copper mining is also important in this area. A narrow plain borders Shikoku’s south coast. There, farmers grow rice and many kinds of vegetables.

The Ryukyu and Bonin islands

belonged to Japan until after World War II, when the United States took control of them. The United States returned the northern Ryukyus to Japan in 1953 and the Bonins in 1968. In 1972, it returned the rest of the Ryukyu Islands, including Okinawa, the largest and most important island of the group.

More than 100 islands make up the Ryukyus. They extend from Kyushu to Taiwan and have about 11/2 million people. The Ryukyu Islands consist of the peaks of a submerged mountain range. Some of the islands have active volcanoes. The Bonins lie about 600 miles (970 kilometers) southeast of Japan and consist of 97 volcanic islands. About 3,000 people live on the islands.

Climate

Climates in Japan vary dramatically from island to island. Honshu generally has warm, humid summers. Winters are mild in the south and cold and snowy in the north. Honshu has balmy, sunny autumns and springs. Hokkaido has cool summers and cold winters. Kyushu and Shikoku have long, hot summers and mild winters.

Two Pacific Ocean currents—the Kuroshio and the Oyashio—influence Japan’s climate. The warm, dark-blue Kuroshio flows northward along the south coast and along the east coast as far north as Tokyo. The Kuroshio has a warming effect on the climate of these regions. The cold Oyashio flows southward along the east coasts of Hokkaido and northern Honshu, cooling these areas.

Seasonal winds called monsoons also affect Japan’s climate. In winter, monsoons from the northwest bring cold air to northern Japan. These winds, which gather moisture as they cross the Sea of Japan, deposit heavy snows on the country’s northwest coast. During the summer, monsoons blow from the southeast, carrying warm, moist air from the Pacific Ocean. Summer monsoons cause hot, humid weather in the central and southern parts of Japan.

Rain is abundant throughout most of Japan. All areas of the country—except eastern Hokkaido—receive at least 40 inches (100 centimeters) of rain yearly. Japan has two major rainy seasons—from mid-June to early July and in September and October. Several typhoons strike the country each year, chiefly in late summer and early fall. The heavy rains and violent winds of these storms often do great damage to houses and crops.

Economy

Japan’s economy is one of the largest in the world in terms of its gross domestic product (GDP). The GDP is the total value of all goods and services produced within a country yearly. Japan is one of the world’s leading countries in the value of its exports and imports. On average, Japanese families enjoy one of the highest income levels in the world, and their assets and savings are among the world’s largest.

Key elements of Japan’s economy are manufacturing and trade. The country has few natural resources, so it must buy such necessities as bauxite (aluminum ore), coal, copper, iron, and petroleum. To pay for those imports, the government has adopted a strategy of exporting manufactured goods of high value.

Manufacturing.

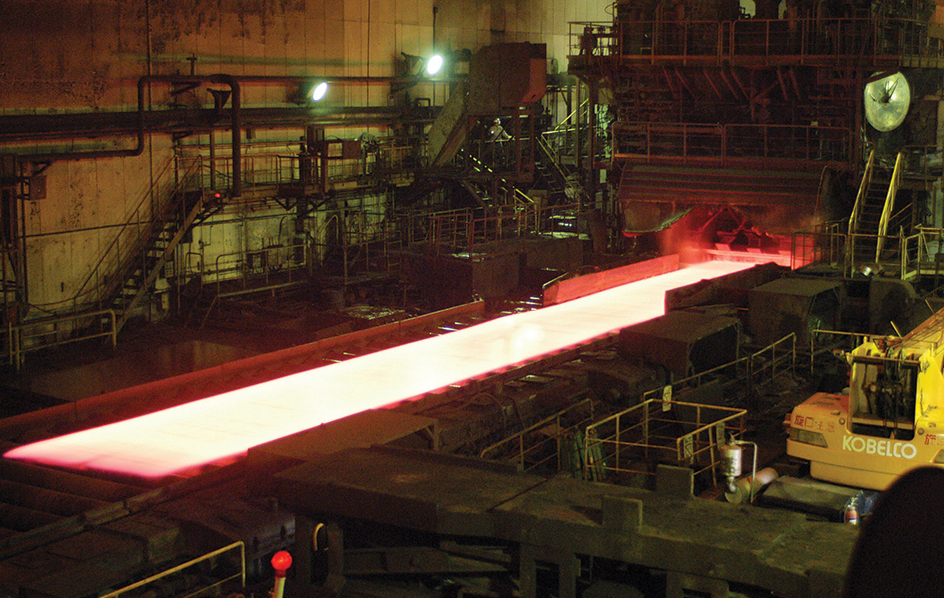

Japan’s manufactured products range from tiny computer components to giant oceangoing ships. The most important manufactured products include cars and trucks, chemicals, electronic products, food products, machinery, and communications and data processing equipment. Japan also produces ceramics, fabricated metal products, plastics, steel, textiles, and watches and other precision instruments.

Japan’s manufacturing sector (portion of the economy) plays a major role in the Japanese economy. Manufacturing industries employ about 15 percent of the Japanese labor force and generate approximately 20 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.

An especially important part of Japan’s manufacturing sector is known as the large-firm sector. It includes such well-known companies as Honda Motor Corporation, Nissan Motor Company, Panasonic Corporation, Sony Corporation, and Toyota Motor Corporation. Most of the large manufacturing firms assemble parts and components into a finished product such as a car, computer, or television set. The large firms then sell the product at a significantly higher price than the cost of the components.

Another part of the manufacturing sector consists of tens of thousands of small factories. Most of these companies make the parts or components that large firms assemble into finished products.

A core group of Japanese managers and skilled workers in the large-firm sector have secure jobs, earn high wages, and enjoy generous benefits. But some workers in the large-firm sector and many in the small factories have less job security, lower wages, and fewer benefits.

Manufacturing in Japan is concentrated in five main regions. For the location of each region and a listing of its main products, see the map titled Economy of Japan in this section of the article.

Construction.

The construction sector consists of several giant national firms, hundreds of medium-sized regional firms, and thousands of small local firms. The sector employs about 8 percent of Japan’s labor force and generates about 6 percent of the GDP.

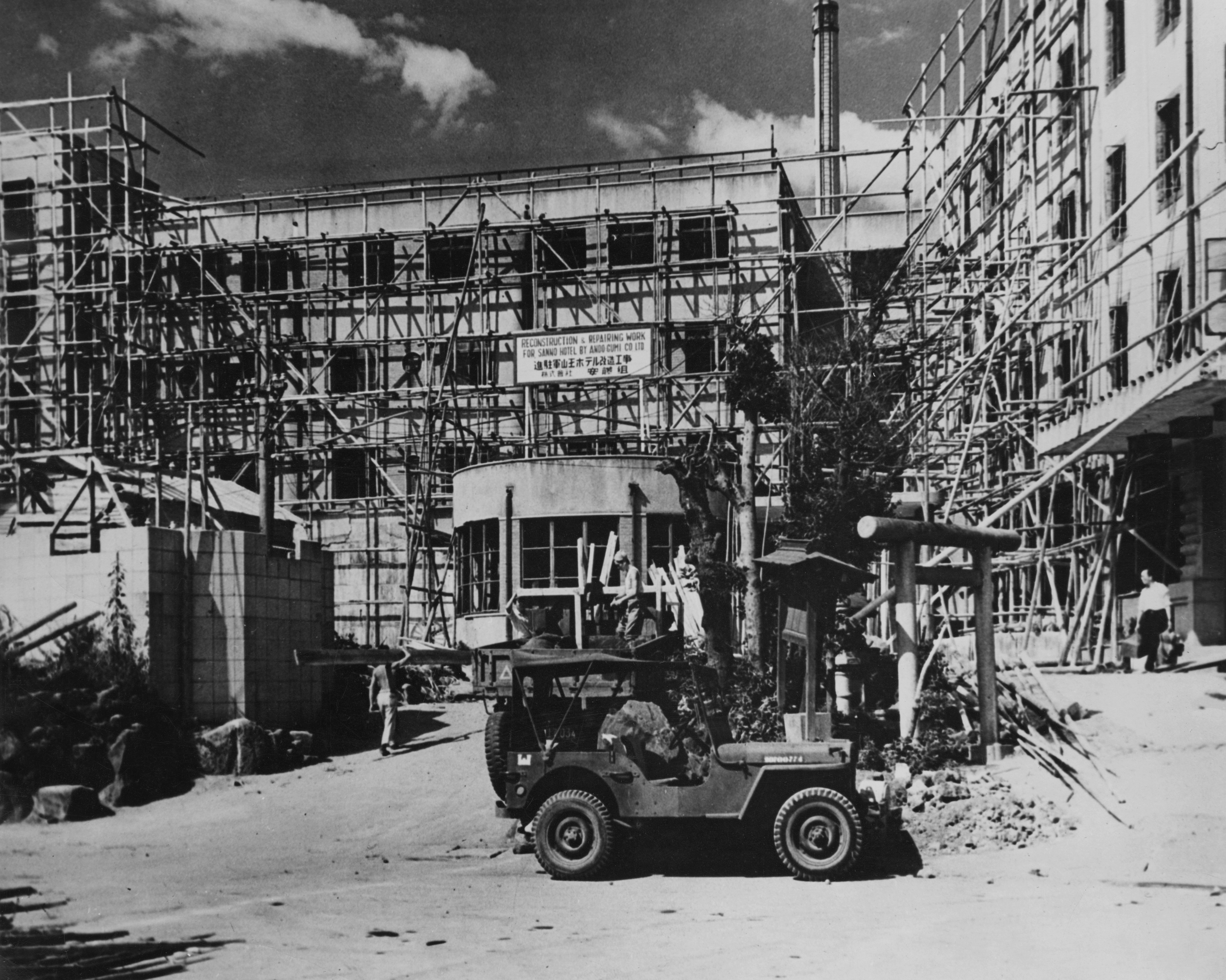

The industry grew dramatically after World War II, when construction firms were needed to rebuild Japan’s ruined cities and demolished factories. Later, the nation’s growing economy brought a constant demand for new shops, offices, factories, roads, harbors, airports, houses, apartments, and condominiums. In the 1990’s, most of the largest firms began to expand internationally. Today, Japanese construction firms build such large projects as hotels and office buildings throughout the world. They handle many projects in other parts of Asia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Mining.

Japan has a wide variety of minerals, but supplies of most are too small to satisfy the nation’s needs. Japan imports large quantities of coal, copper, iron ore, and petroleum. The chief mining products include coal, copper, gold, lead, nickel, and silver.

Agriculture.

Throughout much of Japan’s history, agriculture was the mainstay of the Japanese economy. As late as 1950, the agricultural sector employed 45 percent of the labor force. But as Japan’s industries grew, the economic importance of agriculture declined. By the late 2010’s, farmworkers made up about 3 percent of the labor force, and they produced about 1 percent of the GDP.

Because Japan is mountainous, only about 10 percent of the land can be cultivated. To make their farmland as productive as possible, Japanese farmers use irrigation, improved seed varieties, fertilizers, and modern machinery. Farmers grow some crops on terraced fields—that is, on level strips of land cut out of hillsides.

Rice is Japan’s leading crop. Japan’s farmers also grow apples, cabbage, onions, potatoes, sugar beets, and tomatoes. The country raises beef and dairy cattle, chickens for eggs and meat, and hogs. Much of Japan’s agricultural output comes from Hokkaido.

For decades, government policies have kept crop prices high, especially for rice. Those policies help ensure that Japan has an adequate supply of food, and they protect rural communities from the sudden loss of income. But most Japanese consumers want to reduce the government subsidies so that food becomes less expensive. Other nations want Japan to stop protecting its agricultural sector, so that foreigners can sell rice and other farm products to the Japanese.

Fishing industry.

Japan is one of the most important fishing nations in the world. Japanese fishing crews catch large amounts of anchovies, mackerel, pollock, salmon, squid, and tuna. Other products of Japan’s fishing industry include crabs and other shellfish, and sardines. Workers also harvest oysters and edible seaweed from “farms” in coastal waters.

Japan is one of the few countries in the world that still catches whales. International agreements have sharply limited whaling because many species of whales are near extinction. Some in Japan consider whale meat a delicacy.

Japan’s fishing industry began to decline in the 1950’s. Pollution and international restrictions on ocean catches have reduced the quantity and value of the Japanese catch. Today, few young people enter the industry.

Service industries.

Taken altogether, service industries generate about 70 percent of both Japan’s GDP and its employment. Japan’s leading service industries include community, social, and personal services; finance, insurance, and real estate; and trade. Other service industries that contribute to Japan’s economy include government, and transportation and communication.

Many of the workers in the service industries are highly educated and well-paid. They hold such positions as bankers, financial analysts, civil servants, engineers, teachers, accountants, doctors, and lawyers. Most of these workers are men, and they—as well as managers in the manufacturing industry—are known as sarariman (salarymen). In general, salarymen receive generous incomes and benefits, and they enjoy good job security until they retire in their late 50’s or early 60’s.

However, a number of other workers in the service industries earn lower salaries and have fewer benefits and little job security. They work in such businesses as department stores, movie theaters, restaurants, and the small retail establishments often called “Mom-and-Pop shops.” Such shops sell food, clothing, household necessities, and a variety of other goods. The little shops are far more numerous in Japan than in the United States or Western Europe. But they are disappearing as giant discount stores force them out of business.

Energy sources.

Japan requires large amounts of energy to power its factories, households, offices, and motor vehicles. But the nation must import most of the fuel required to produce that energy. Japan has limited natural supplies of petroleum. Hokkaido and Kyushu contain fairly large deposits of coal, but its quality is poor, and the deposits are difficult to mine.

Nevertheless, Japan ranks among the world’s leading consumers of electric power. Power plants that burn coal, natural gas, or petroleum produce most of Japan’s electric power. Hydroelectric plants produce a small amount of electric power.

Before an earthquake and tsunami hit Japan in March 2011, nuclear power plants generated about 25 percent of the country’s electric power. However, the tsunami damaged a nuclear power plant that released dangerous amounts of radioactivity. In the aftermath of the disaster, the government shut down all of Japan’s nuclear power plants for maintenance and safety inspections. Several plants were restarted in the following years.

International trade.

In many ways, the driving force of Japan’s economy is international trade. By trading with other nations, Japan obtains the raw materials it does not have and finds buyers for the expensive, high-quality manufactured goods its workers produce. Japan’s chief trading partners include Australia, China, Germany, South Korea, Taiwan, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States.

Japan’s largest single import is crude oil. Other major imports include chemicals, fish and shellfish, machinery, and natural gas. Japan exports chemicals, electrical equipment, machinery, motor vehicles, scientific and optical equipment, and semiconductors.

To find buyers for Japan’s expensive products, the nation looks to wealthy countries in North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. Since the end of World War II, the United States has bought the largest share of Japan’s exports. In the 1950’s, the United States purchased inexpensive Japanese textile products. Later, it began to buy more costly goods, such as automobiles and communications and computer equipment.

The United States sells Japan many American goods in return, including expensive items, such as computers and medicines. However, Japanese trade barriers place restrictions on many imports. By the 1980’s, the United States was buying far more from Japan than it was selling to it. The inequality led to a large trade imbalance between the two nations. In the early 1990’s, a similar imbalance arose between Japan and the nations of North and East Asia and Western Europe.

Japan’s trade surpluses enabled it to accumulate huge reserves of foreign currency, in an amount that was second only to the foreign reserves of the United States. Japan used some of its reserves to invest in factories, banks, businesses, and real estate in the United States and many other countries.

Just as Japan was reaping these successes, Canada, the United States, and Western Europe were suffering economic slowdowns. People in other nations began to envy and resent Japan for its trade surpluses, large reserves of foreign currencies, and heavy investment in other countries. Under pressure, Japan began to lift some of its trade barriers.

Transportation.

Japan has a modern transportation system, including airports, highways, railroads, and coastal shipping. All the major cities have extensive local transit networks that include buses, trains, and subways. Japan also has the world’s longest suspension bridge, the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge. The bridge has a main span of 6,529 feet (1,990 meters). It connects Kobe and Awaji Island and thus provides a link between the island of Honshu and the island of Shikoku.

A multicompany business unit known as Japan Railways Group operates much of the Japanese railroads. Trains traveling between Honshu and Hokkaido go through an undersea tunnel called the Seikan Tunnel. At 33.5 miles (53.9 kilometers) long, it is one of the world’s longest transportation tunnels.

Japan’s commercial fleet is one of the world’s largest. Japan’s chief ports include Chiba, Kobe, Nagoya, and Yokohama. Hundreds of smaller ports and harbors enable coastal shippers to serve every major city in Japan.

Japan has a large number of airports. The busiest airports include Tokyo International, commonly called Haneda; Narita International at Tokyo; Kansai International at Osaka; and Central Japan International, commonly called Chubu Centrair, at Nagoya. Haneda handles most of the domestic flights of Japan. The other three handle most of the country’s foreign air traffic.

Communication.

Japan has thriving publishing and broadcasting industries. The nation has dozens of daily newspapers. The largest dailies include the Asahi Shimbun and Yomiuri Shimbun, both of Tokyo. Each year, Japanese publishers produce tens of thousands of new books and thousands of periodicals, including popular comic books, called manga, for both adults and children.

Japan’s main radio and television broadcasting is handled by the government. These programs are funded by yearly license fees from households that own television sets. Commercial radio and television stations broadcast local and national programming.

History

Early days.

People have lived on the islands of Japan for more than 30,000 years. The earliest inhabitants lived by hunting and gathering food and made tools out of stone. Historians refer to the period of Japanese history between about 10,000 and about 300 B.C. as the Jomon era. During this time, people lived in small villages of about 50 people. To obtain food, they hunted for deer and boar, fished, and gathered nuts and berries. The main artifacts these people left behind were pots with markings made by cords or ropes. Jomon means cord-marked.

Near the end of the Jomon era, people in Japan learned new ideas and new technologies from contact with Korea and China. The Japanese learned how to grow rice in irrigated fields, and they began to settle in communities near the rice paddies. They also learned how to make tools and weapons out of bronze and iron. This period is called the Yayoi era (about 300 B.C. to about A.D. 300).

By the end of the Yayoi era, different groups of extended families began to struggle for power in the Yamato Plain. The plain lies southeast of modern Kyoto. When the leaders of these groups died, their relatives buried them in large tombs called kofun that were often shaped like keyholes. The period of Japanese history from about 300 to 710 is often known as the Kofun era. It is also sometimes called the Yamato period. The tombs were surrounded with small clay sculptures called haniwa. Many haniwa are figurines of warriors or sculptures of bows and arrows, a sign that warfare had become an important part of Japanese society.

Chinese influence.

In the 600’s and 700’s, one of the extended family groups began to dominate the others, and it declared itself Japan’s imperial household. By tradition, the imperial family has no family name. The head of the imperial house, whose given name was Kotoku, became emperor in 645.

The next year, the imperial family began a program called the Taika Reform. The program involved constructing capital cities and organizing Japanese society following the example of China. The imperial family created a central government and official bureaus and adopted a system of land management similar to China’s. Under this system, most people worked as farmers on land the government owned. In return, the farmers paid taxes to the government and provided labor, including service in the government’s small armies.

To justify its claim to authority, the imperial family relied not on China but on ancient Japanese beliefs. Japanese histories written in the 700’s maintain that the family had descended from the gods who created the Japanese islands in Japanese mythology. The family’s presumed descent was through Amaterasu, the Japanese sun goddess.

Heian era.

In 794, the imperial household moved to a new capital city called Heian-kyo, located at the site of today’s Kyoto. During the next 400 years, Heian-kyo was the center of Japan’s government and nobility.

During the Heian era, a male in the imperial household ruled as emperor. The male heads of noble families assisted the emperor by administering the government, collecting tax revenues, maintaining small armies, and judging legal disputes. These officials earned generous incomes and lived in large mansions in the capital city.

The ruling nobles used their leisure time primarily to observe nature and write poetry. Female members of the nobility, who were barred from holding office, had the most time for these pursuits. Women produced the era’s most famous writings, including The Tale of Genji.

During the Heian era, the leading noble families undermined the power of the emperor and his government. One such family was the Fujiwara, who gained power by intermarrying with the imperial family.

Creation of private estates.

As the central government’s power declined during the Heian era, a new type of institution emerged—the shoen (private estate). Private estates were plots of land whose owners were free from government interference and taxation. The government began to establish these estates in the 700’s to provide Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines with income to fund their religious activities. Gradually, the religious institutions became major landholders.

During the 700’s, the government also began to allow tax exemptions to those who developed new lands for growing rice. The aristocratic families and religious institutions that had enough wealth to develop new lands acquired large holdings. Later, the Fujiwara and other high-ranking families in Heian-kyo used their influence to obtain ownership of other public lands. In the late 1000’s, even retired emperors began taking land. By the 1200’s, about half of the rice-growing land in Japan had been converted into private estates.

As the influence of the private estate owners increased, the power of the central government declined. With less public land, the government had less tax revenue to support its activities. The government and the aristocrats in Heian-kyo had to rely on bands of professional soldiers called samurai to protect the land and keep order in the countryside.

Rise of the shogun.

By the 1100’s, two large military clans—the Taira and the Minamoto—had armies of samurai under their command. Both clans were descendants of the noble families at court. In the late 1100’s, the Taira and Minamoto clashed in a series of battles for power. The Minamoto finally emerged victorious in the 1180’s.

The Minamoto established a new military government headquartered in Kamakura, a town in eastern Japan far from Heian-kyo. In 1192, the head of this military government, Yoritomo, was given the title of shogun, a special, high-ranking military post granted by the emperor. His military government became known as a bakufu or shogunate.

Although Yoritomo was the emperor’s special commander, he established his own separate bases of power. He assumed control of the administration of justice. He began to place nobles who had sworn loyalty to him on private estates and appointed others to oversee the remaining public lands. In this way, the shogun began to influence both areas of power in Japan—the imperial government and the private estates.

By the early 1200’s, Japan’s political situation had become highly unstable. The imperial government’s influence was limited and declining. Private estate owners were struggling to retain control over their lands as the shogun’s ambitious supporters expanded their influence.

The next 200 years brought waves of conflict and change. First, the Minamoto family lost its influence to members of the Hojo family, who ruled as agents in the name of the Minamoto shoguns. Then the military government in Kamakura fell to the superior force of another clan, the Ashikaga. The Ashikaga established a new military government in Kyoto in the 1330’s. Gradually, the clan lost control of the nobles under its command. By the 1460’s, Japan had no effective central political authority.

Warring states period.

In the century after the 1460’s, Japan was an armed camp. Peasants in the countryside were forced to take up swords to protect their communities. Temples with large landholdings trained their own armies of warrior-monks to protect their assets. Some estate owners gathered private armies of samurai to guard their lands. Samurai without masters roamed the country offering to fight for pay.

The most powerful samurai became regional lords called daimyo. They exercised control over many armed warriors and governed large areas of farmland. They fought each other for military supremacy during the 1500’s, as Japan sank into a long period of civil war.

In 1549, Saint Francis Xavier, a missionary from Portugal, arrived in Japan and introduced a new element into this unstable scene. Xavier and a few other priests had come to convert the Japanese populace to Christian beliefs. The missionaries also intended to help Portuguese traders sell European luxury goods and up-to-date weapons to the Japanese.

The priests had little success in converting the Japanese to Christianity. But the traders found eager customers among the daimyo in southern Japan. The guns they sold were an explosive addition to the civil wars.

One regional lord who made much use of the weapons was Oda Nobunaga. Nobunaga was a ruthless warrior with a keen desire for power. In the 1560’s, he gathered a large coalition of forces under his command and led them to Kyoto. He brought order to the capital district. He was beginning to impose control on other areas of Japan when he was killed in 1582.

Nobunaga’s successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, took up the task of uniting the nation. Hideyoshi carried out several reforms with far-reaching effects. He disarmed the peasantry. He brought many of the unruly samurai under his control. And he surveyed most of the usable farmland in the country. Hideyoshi tried to extend his power to Korea in the 1590’s. Twice he tried to conquer Korea, but both times he failed.

Tokugawa period.

Hideyoshi was succeeded by a noble named Tokugawa Ieyasu, who had also served Oda Nobunaga. In 1603, the emperor gave Tokugawa Ieyasu the title of shogun. For the next 265 years, leaders of the Tokugawa house governed Japan as shogun.

The Tokugawa shogun presided over a delicately balanced system of authority. The shogun directly controlled about 25 percent of the farmland in the country. He also licensed foreign trade, operated gold mines, and ruled the major cities, including Kyoto, Osaka, and the shogun’s capital—Edo, which is now Tokyo.

The Tokugawa shogun had to share authority with the daimyo, who controlled the remaining 75 percent of Japan’s farmland. The number of daimyo during the Tokugawa period averaged about 270. Each of these daimyo governed his own han (domain). In each han, the daimyo, not the shogun, issued laws and collected taxes. During the Tokugawa era, Japan thus had only a partially centralized government.

By the early 1600’s, Japan was also home to five groups of foreigners: the Portuguese, Spanish, English, Dutch, and Chinese. Their presence disturbed the shogun, in part because the Tokugawa did not support Christianity, the religion of most of the outsiders. In addition, the shogun wanted to control Japan’s international trade to prevent any daimyo from gaining too much wealth and power through trade with the outsiders.

For these reasons, the Tokugawa had most foreigners expelled from Japan during the 1630’s under orders known as seclusion edicts. Only a few Dutch and Chinese traders were allowed to remain in Japan to conduct their business. But they could live only in the distant city of Nagasaki. That town served as Japan’s sole window on the European world until the mid-1800’s.

Japan had now put an end to centuries of internal wars and had closed itself off from the rest of the world. During this period of peace and isolation, the nation began to pursue its own course of development.

At this time, Japan laid the foundation for its future economic growth. People in all walks of life developed a strong work ethic and devotion to their craft and duty. Hard-working farmers in the countryside and merchants in the cities saved money and learned to invest it wisely. Trading firms in the large cities developed skills in finance, organization, and personnel management.

Entertainment and the arts also flourished, particularly in Edo. In the 1700’s, Edo became one of the world’s largest cities. It developed thriving industries to entertain the many samurai and merchants living there. Entertainers perfected the form of stage drama called kabuki and the puppet theater called bunraku. The entertainment districts, called ukiyo (the floating world), became the subjects of a new Japanese art style named ukiyo-e. Colorful wood-block prints in this style depicted the men and women of the entertainment districts.

But the Tokugawa era was also a time of critical difficulties. The military government grew dull and strict. It discouraged individual freedoms and slowed commercial development. Government financial problems led to cuts in the income of samurai. Their declining incomes added to the samurai’s growing dissatisfaction with Japan’s rigid social structure, which prevented them from rising to better stations in life. Finally, poor harvests and harsh lords drove many peasants to join together in protest.

Renewed relations with the West.

In 1853, renewed contact with the West led directly to sweeping changes. That year, a small fleet of American naval vessels sailed into the bay south of Edo. The fleet’s commander, Matthew C. Perry, asked Japan to open its ports to international trade.

The shogun rebuffed Perry, but Perry returned in 1854. After many discussions, Japan allowed the United States to station a negotiator, Townsend Harris, in the small port of Shimoda, far from Edo. In 1858, Harris succeeded in his negotiations on behalf of the United States, and Japan signed a treaty of commerce. The treaty permitted trade between the two countries, called for opening five Japanese ports to international commerce, and gave the United States the right of extraterritoriality. This right enabled American citizens to be governed only by U.S. laws while they were on Japanese soil.

Many Japanese disapproved of the treaty and similar agreements signed later. To them, the treaties were unequal, because Japan had granted extraterritoriality and other privileges that were not given to the Japanese in turn. The treaties enraged many samurai, who attacked and killed some foreign officials. The samurai also plotted to overthrow the government of the shogun.

Meiji era.

In 1867, a small group of samurai and aristocrats pressured the shogun into resigning and restored the emperor to his previous position as head of the government. The revolutionaries disapproved of the trade treaties and wanted to increase Japan’s security and well-being in what they considered a dangerous and competitive world. They acted without the support of the Japanese people.

On Jan. 3, 1868, the emperor officially announced the return of imperial rule. The emperor, a teenager named Mutsuhito, adopted Meiji, meaning enlightened rule, as the name for the era of his reign. He reigned from 1868 to 1912, a span of time known as the Meiji era. The revolution that placed him in power is known as the Meiji Restoration.

In practice, however, the leaders of the Meiji Restoration and their successors ruled the country, not the emperor. The leaders adopted the slogan “Enriching the Nation and Strengthening the Military” as their guiding policy. By enriching Japan, the new leaders believed they would enable the nation to compete with the Western powers.

To compete in the late 1800’s meant building modern industries. And so Japan embarked on an ambitious program of economic development. The nation invested in coal mines, textile mills, shipyards, cement factories, and many other modern enterprises.

Few of these ventures were successful, however. In the 1880’s, the government began selling its industries to private companies. Some of these companies, such as the Mitsui and Sumitomo groups, were old merchant houses that had been in business since the 1600’s. Others, such as the Mitsubishi group, sprang up after the Meiji restoration. From the 1880’s to the 1940’s, these business enterprises grew large and rich. These conglomerates became known as zaibatsu.

Most zaibatsu were owned and operated by a single family or a family group. They created many related ventures, especially in banking, insurance, international trade, manufacturing, and real estate. The zaibatsu cooperated with the government to promote its aim of enriching the nation. But they remained private enterprises that enriched themselves at the same time.

The second strategy of the Meiji leadership was to strengthen Japan’s military force. Former samurai took charge of a modern military recruited from the sons of farmers. With the advice of European military experts, the government built naval shipyards and assembled military arsenals. Within 20 years after the Meiji restoration, Japan had developed the best military force in East Asia.

From 1868 to 1889, government leaders also experimented with different methods of organizing the nation’s political institutions. In 1889, they produced Japan’s first Constitution. This document made the emperor the head of the government and established a cabinet of ministers and a legislature with two houses. The Constitution spelled out the rights and duties of the citizens, and it created a system of courts.

Under this Constitution, the powers of the Japanese people were extremely limited. The leaders of the restoration and their appointees continued to hold real power. These men now served in official roles as prime ministers and Cabinet members.

Another aim of the new government was to reorganize society. The nation removed restrictions that had prevented people from pursuing any occupation they desired. New laws made the family the basic unit of society and males the heads of households. Some of these laws limited women’s rights more drastically than they had been during the Tokugawa era of the 1600’s to mid-1800’s.

Finally, the government established an ambitious system of public education. By the early 1900’s, Japan offered free elementary education to most young people. More advanced, specialized schooling was available to students who had the money and talent to proceed further. This school system made it possible for many people to improve their status in society. It greatly assisted Japan’s economic development. The schools also cultivated in students a strong sense of national pride and superiority.

Imperialism.

In due course, the Meiji government’s emphasis on military might and the educational system’s emphasis on Japanese superiority led to war. In 1895, Japan began to build an empire like those of Britain and other European powers. Three Asian regions were the initial targets of Japanese expansion: Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria.

After defeating China in a short war, Japan assumed control over Taiwan in 1895. The Japanese then exploited Taiwan as an agricultural colony producing rice and sugar.

Korea fell under Japanese control in 1910, following a bitterly fought war between Japan and Russia in 1905. Japan exploited Korea for its rice and its potential to develop industries. Remembering stories of Toyotomi’s invasions in the 1590’s, Koreans fiercely resented Japan’s colonization. The Japanese treated them badly in return.

The Russo-Japanese War also gave Japan a small foothold in Manchuria. There, Japan’s army of occupation gradually expanded its control.

World War I began in 1914. Japan, as an ally of Britain, at once declared war on Germany. The war gave Japan an opportunity to enlarge its empire slightly. More important, the war gave Japan an economic advantage in India and the rest of Asia. As Western nations became preoccupied with the war in Europe, they stopped their investment and trade in the East. Japanese exporters and manufacturers took that opportunity to move into Indian and other Asian markets. The zaibatsu expanded, and Japan’s economy boomed.

Rise of militarism.

The 1920’s were a time of great difficulties for Japan. After the war, Western nations re-established trade with India and the rest of Asia, and the Japanese economy suffered. In 1923, a terrible earthquake struck the Tokyo-Yokohama area and led to the deaths of about 143,000 people. A worldwide depression during the late 1920’s further hurt the Japanese economy.

About this time, China began to strengthen its administration in Manchuria. Japan feared it might lose the rights it gained in the Russo-Japanese War.

Japan’s prime minister and other government leaders could not deal with the problems troubling Japan. Officers in the Japanese army decided to take matters into their own hands. In 1931, the Japanese occupation force took control of Manchuria. At home, nationalist groups began to threaten members of the government who opposed the army. On May 15, 1932, nationalists assassinated Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai.

By 1936, Japan’s military leaders were in firm control of the government. As Japanese armies marched across China and into Southeast Asia, the United States grew increasingly concerned. Meanwhile, Japan moved toward closer relations with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy by signing anti-Communist pacts with the two nations.

World War II

began in Europe in September 1939. In September 1940, Japanese troops occupied the northern part of French Indochina. When they moved into the southern part of Indochina the next year, the United States cut off its exports to Japan.

In the fall of 1941, General Hideki Tojo became prime minister of Japan. Japan’s military leaders began preparing to wage war against the United States.

Japanese bombers attacked the U.S. military bases at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941. They also bombed U.S. bases on Guam and Wake Island and in the Philippines. The bombing brought the United States into war against Japan and Japan’s European allies, Germany and Italy. Loading the player...

Attack on Pearl Harbor

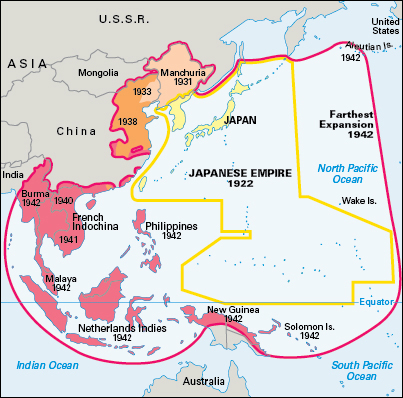

Japan quickly won dramatic victories in Southeast Asia and in the South Pacific. By 1942, the Japanese empire spanned much of the area from the eastern edge of India through Indonesia, and from the Aleutian Islands near Alaska to the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific Ocean.

The Japanese fleet suffered its first major setback in May 1942, when the United States Navy, with assistance from the Royal Australian Navy, fought the Battle of the Coral Sea to a draw. The U.S. victory in the Battle of Midway the following month helped turn the tide in favor of the United States. As Japanese defeats increased, political discontent in Japan grew. On July 18, 1944, Prime Minister Tojo’s Cabinet fell.

Early in 1945, the battle for the Japanese homeland began. American bombers hit industrial targets, and warships pounded Japanese coastal cities. American submarines cut off the shipping of vital supplies to Japan. On August 6, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare on the city of Hiroshima. Two days later, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria and Korea. The next day, U.S. fliers dropped a second and larger atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

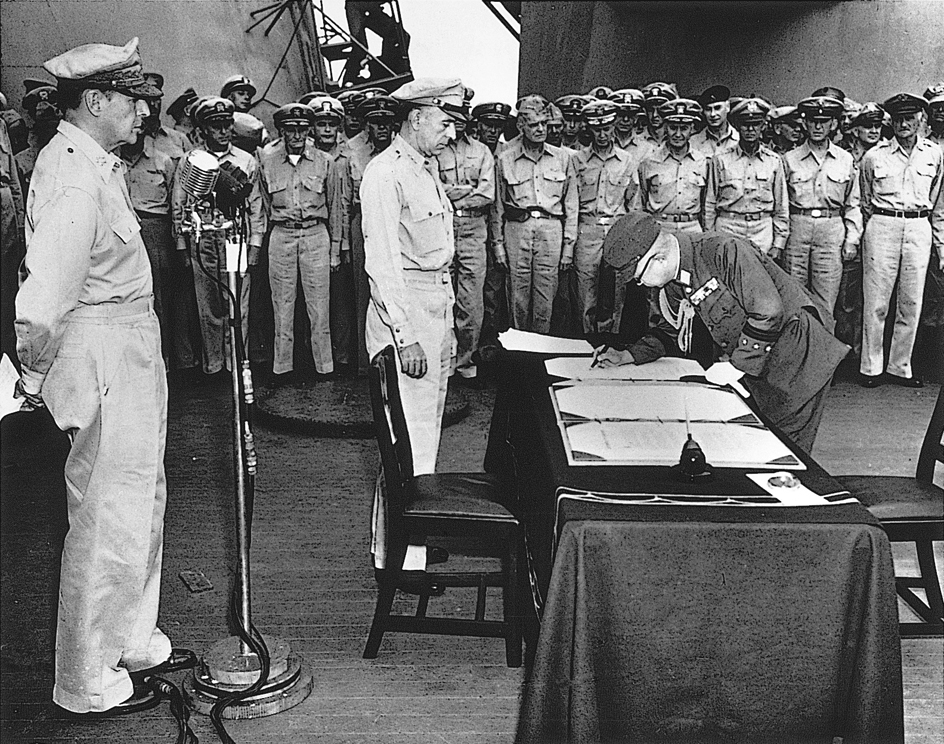

Japan agreed to surrender on August 14. The next day, Emperor Hirohito announced to the Japanese people that Japan had agreed to end the war. On Sept. 2, 1945, Japanese officials officially surrendered aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

As a result of the war, Japan lost all its territory on the mainland of Asia. It also lost all the islands it had governed in the Pacific. The nation kept only its four main islands and the small islands nearby. In the 1950’s, 1960’s, and 1970’s the United States returned to Japan the Bonin Islands, Iwo Jima (now Iwo To), and the Ryukyu Islands. Russia still occupies the Kuril Islands.

Allied military occupation.

Japan’s defeat brought foreign occupiers to its shores for the first time in its long history. Under the direction of U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, the occupation force carried out a sweeping set of reforms inspired by American ideals. The Japanese government served only to carry out MacArthur’s orders.

Under the occupation, more than 5 million Japanese troops were disarmed. The Allies tried 28 Japanese leaders and more than 5,000 soldiers for war crimes. More than 900 Japanese were executed, and most of the others were sent to prison.

The Allied occupation force began reforms in 1946, when MacArthur and his advisers drew up a new Japanese Constitution. Under this document, the emperor lost all real power and became merely a symbol of the state. The two-part legislature became Japan’s supreme lawmaking body. A civilian prime minister, chosen by majority vote in the legislature, became head of the government. The rights of the people increased dramatically compared with those granted by the Meiji Constitution.

The American occupiers also began economic and social reforms. They redistributed farmland, legalized labor unions, and encouraged new laws giving women and children greater rights. The Americans also reorganized Japan’s educational system to make it more democratic.

In 1951, Japan signed a peace treaty with 48 nations that went into effect on April 28, 1952. The Allied occupation officially ended on that day.

Postwar boom.

The Japanese economy suffered greatly from World War II. Allied bombing destroyed many of the nation’s factories and nearly leveled most large cities. Many Japanese were forced out of work. Much of the population lived in dire conditions in small rural villages, and they depended on friends and neighbors to survive.

Japan was almost closed off from the outside world because many of its trading ships had been destroyed. The value of its currency, the yen, dropped so low that Japan could not afford to purchase many foreign goods.

Recovering from these losses took about a decade of effort. The United States provided financial assistance, but the Japanese national government played the central role in promoting reconstruction.

After the war, the government began to guide and direct the nation’s industries. The government formed the Ministry of International Trade and Industry to identify the industries in Japan that needed to be developed. Then the Ministry of Finance directed investment funds toward these enterprises. The Japanese tradition of working hard, saving money, and investing wisely helped the nation become economically stable. By the mid-1950’s, the output of most Japanese industries matched their prewar levels.

From 1955 to 1993, a single conservative party called the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) dominated national politics. The Liberal Democratic Party consistently won the most seats in the Diet as well as in the prefectural and local assemblies. The LDP strongly advocated Japan’s economic growth, and it put into effect many successful policies.

Many social changes occurred during the postwar years. Fewer and fewer people stayed in rural areas to earn a living by farming. Instead, they moved to cities and became workers in manufacturing or service industries. Families saw their incomes doubling and tripling within a generation.

Cooperation and harmony continued to be prized ideals in Japan. But the pressures to conform to society’s expectations were less apparent in large cities than in the small villages. Young people felt freer to be individuals than their parents and grandparents had.

Even the imperial family took part in some changes. In 1959, Crown Prince Akihito broke tradition by marrying a commoner, Michiko Shoda, the daughter of a wealthy industrialist. In 1971, Emperor Hirohito and Empress Nagako visited Western Europe. This visit marked the first time that a reigning Japanese emperor had ever left the country.

Political changes.

Emperor Hirohito died in 1989, and his son, Akihito, began to reign. It soon began to appear that Akihito’s era would be a time of unsettling political and economic change.

Troubles for Japan’s long-term ruling political party, the LDP, began in the 1980’s. A number of leading government figures were accused of raising campaign funds illegally. Some were tried and convicted of corruption. Voters began to turn against the LDP. In mid-1993, the party lost its majority in the Diet.