Jefferson, Thomas (1743-1826), was the third president of the United States. He was also a leading figure in America’s movement toward independence and development as a nation. Jefferson was a tall man with red hair. He was a native of central Virginia, where he became a leading lawyer and plantation owner. During the American Revolution (1775-1783), he rose to a position of leadership in both his state and the nation, most famously as the author of the Declaration of Independence. After the Americans won independence from Great Britain (later also called the United Kingdom), Jefferson held political office almost continuously until his retirement in 1809. He was president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. His presidency was a period of tremendous growth for the nation.

In addition to his two terms as president, Jefferson served in many other offices. He was a member of the Virginia legislature, a delegate to the Continental Congress, governor of Virginia, U.S. minister to France, U.S. secretary of state, and vice president of the United States. He also was a lifelong supporter of the arts, sciences, and education.

Jefferson was a transitional figure between the age of monarchy and the age of democracy. His political ideology was firmly within the tradition of the English Whigs. The Whigs believed the power of rulers, including monarchs, came from the people and should be limited. Jefferson embraced many of the ideas of the Enlightenment, a period from the 1600’s to 1700’s. During the Enlightenment, philosophers emphasized the use of reason and science. Jefferson was greatly influenced by the ideas of the English philosopher John Locke. Locke emphasized basic human rights and believed that people should revolt against governments that violated those rights. Jefferson also was influenced by such political writers as James Harrington and Algernon Sidney of England and Montesquieu of France. Historians often disagree over which thinkers affected Jefferson the most.

Jefferson’s defenses of individual liberty and representative government continue to inspire people today. The term Jeffersonian democracy has come to refer to Jefferson’s ideal of rule by the people with minimum government interference. Jefferson felt that local governments—those closest to the people being governed—should be the most powerful. He felt that distant general governments should have only limited powers. Jefferson argued for freedom of speech, of the press, and of religion. He pressed for the addition of a bill of rights to the Constitution of the United States. However, many modern critics point out that, despite his public support for civil liberties, Jefferson held Black laborers in slavery throughout his adult life.

Beyond politics, Jefferson’s interests and talents were wide-ranging. He was one of the leading American architects of his time, designing the Virginia Capitol, the University of Virginia, and his own home, Monticello (see Monticello). He greatly appreciated art and music and encouraged their advancement in the United States. Jefferson also served as president of the American Philosophical Society, an organization that encouraged a wide range of scientific and intellectual research.

Early life and family

Boyhood.

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743, at Shadwell, the family farm in Goochland (now Albemarle) County, Virginia. (The date was April 2 by the calendar then in use.) Thomas was the third child in the family and grew up with six sisters and one brother. Two other brothers died in infancy. His father, Peter Jefferson, had served as a surveyor, sheriff, colonel of militia, and member of Virginia’s House of Burgesses, a colonial legislative body. Thomas’s mother, Jane Randolph Jefferson, came from one of the oldest families in Virginia.

Thomas was 14 years old when his father died. As the oldest son, he became head of the family. He inherited more than 2,500 acres (1,010 hectares) of land and at least 20 enslaved Black Americans. Thomas’s guardian, John Harvie, managed the estate until Jefferson was 21.

Education.

The colony of Virginia had no public schools, so Thomas began his studies under a tutor. At age 9, he went to live with a Scottish clergyman who taught him Latin, Greek, and French. After his father died, Thomas entered the school of James Maury, an Anglican clergyman, near Charlottesville.

In 1760, when he was 16, Jefferson entered the College of William and Mary at Williamsburg. The town had a population of only about 1,000. But as the provincial capital, it had a lively social life. There, young Jefferson met two men, William Small and Judge George Wythe, who would have a great influence on him.

Small, a Scot who had been educated in Aberdeen, was a professor at the college. It was through Small that Jefferson was exposed to Enlightenment thinkers from Europe. A number of writers from England and Scotland—such as John Locke, Algernon Sidney, Francis Hutcheson, and Henry Home, Lord Kames—would prove enormously influential to Jefferson’s political philosophy. In addition, the writings of the English statesman Viscount Bolingbroke had a significant impact on Jefferson’s religious beliefs. Jefferson had been raised in the Anglican Church, but he soon developed a distrust of organized religion. He continued to attend Anglican services, but his religious views came to resemble those of the Unitarians, who emphasize the unity of God rather than the doctrine of the Trinity.

Small introduced Jefferson to Wythe, one of the most learned lawyers in the province (see Wythe, George). Through Small and Wythe, Jefferson became friendly with Governor Francis Fauquier. It was during these years as a student that Jefferson also met Patrick Henry, who would later become a distinguished lawyer, statesman, and orator. Jefferson spent two years at William and Mary. Like most college students at the time, he did not earn a degree.

Lawyer.

After leaving college in 1762, Jefferson studied law with George Wythe. Because there were no formal law schools in the colonies at that time, Jefferson’s studies involved reading law books under Wythe’s supervision and watching Wythe practice law in court.

Jefferson was admitted to the bar (legal profession) in 1767. He practiced law with great success until public service began taking all his time. He divided his time between Williamsburg and Shadwell. At Shadwell, he designed and supervised the building of his new home, Monticello, on a nearby hill. Jefferson’s estate, like that of his father, lay in the rolling hills of Virginia’s Piedmont region, in what is now Albemarle County.

Jefferson’s family.

In 1772, Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton (Oct. 19, 1748-Sept. 6, 1782), a widow. The couple, who shared a love of music and literature, settled at Monticello while it was still under construction. The Jeffersons had one son and five daughters, but only two children lived to maturity—Martha (1772-1836) and Mary (1778-1804). Mrs. Jefferson died in 1782, after complications arising from childbirth. Thomas Jefferson never remarried.

Mrs. Jefferson’s father was John Wayles, a prominent lawyer who lived near Williamsburg. After Wayles died in 1774, he left a large inheritance to the couple. The inheritance included about 11,000 acres (4,450 hectares) of land, including the Poplar Forest plantation in Bedford County, and 135 enslaved people. One of the enslaved people was Elizabeth (Betty) Hemings, with whom Wayles had fathered several children.

In addition to land and enslaved laborers, the Wayles inheritance left Jefferson with the debts that Wayles had owed. Jefferson immediately sold much of the land to pay off some of the debts. But the remainder of the Wayles debt would trouble him for decades to come.

Slave ownership.

Enslaved Black people were a vital part of the plantation community at Monticello and other farms that Jefferson owned. Jefferson hired some white laborers, but enslaved people performed the vast majority of the work. Enslaved workers planted and harvested wheat, tobacco, and other crops; constructed buildings and furniture; and were responsible for cooking, cleaning, and other household chores. Jefferson freed a few people from slavery during his life, but he did not attempt to free all, or even most, of his enslaved people in his will.

Jefferson and Sally Hemings.

In the early 1800’s, rumors began circulating that Jefferson had engaged in a sexual relationship and fathered children with one of the people he held in slavery, Elizabeth Hemings’s daughter Sally Hemings (1773–1835). Some historians believe it is likely that John Wayles was Sally’s father, and that Jefferson’s wife and Sally Hemings were half-sisters. One of Sally Hemings’s sons, Madison Hemings, later claimed that he was Jefferson’s son and that the relationship between his mother and Jefferson began during Jefferson’s mission to France in the 1780’s. The rumors caused a great deal of controversy during Jefferson’s life, and they remained a topic of debate among historians for many years.

In 1998, the science journal Nature published a study in which scientists analyzed genetic material from Jefferson and Hemings descendants, looking for evidence of a relationship. The scientists examined the descendants’ DNA, in particular the Y chromosome, which is almost always passed unchanged from father to son. The study compared the DNA from male-line descendants of Jefferson’s uncle with DNA from male-line descendants of two of Sally Hemings’s sons. The study could not include male-line descendants of Jefferson and his wife because they had no sons who lived to adulthood. The authors concluded that Jefferson could have fathered at least one of Hemings’s children, Eston Hemings.

However, the scientists acknowledged that their study did not include the descendants of other male Jeffersons, particularly of Jefferson’s brother Randolph, who had five sons. These relatives carried the same Y-chromosome characteristics as Thomas. The authors of the study later conceded that these relatives could have fathered one or more of Hemings’s children.

After the Nature study was published, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which owns and operates Monticello, appointed a committee to review the controversy. Committee members examined historical and scientific documents and interviewed descendants of the enslaved people at Monticello, among others. In early 2000, the foundation announced that the likelihood is strong that Jefferson and Sally Hemings had a long-term relationship and that Jefferson was the father of at least one, if not all six, of Hemings’s children. Although most professional historians acknowledge a relationship between Jefferson and Hemings, some people do not, and the matter remains deeply controversial.

Colonial statesman

Revolutionary leader.

Jefferson was elected to Virginia’s House of Burgesses (later the Virginia House of Delegates) in 1769 and served there until 1775. He was not a great public speaker but proved himself to be an able writer of laws and resolutions.

Jefferson became a member of a group of statesmen that included Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and Francis Lightfoot Lee. These men challenged the control that political elites known as Tidewater aristocrats held over Virginia’s government. They also took an active part in the ongoing disputes between colonial leaders and the British Parliament. In 1769, the men organized a nonimportation association to protest the import duties created by the British government’s Townshend Acts. The Virginians resolved to not buy any British goods until Parliament repealed the duties.

In 1774, the British government passed a series of laws to strengthen British authority in Massachusetts. These laws became known in America as the Intolerable Acts or the Coercive Acts. After their passage, Jefferson took the lead in organizing another nonimportation agreement. He also called for a meeting of all the colonies to consider their grievances.

Jefferson was chosen to represent Albemarle County at the First Virginia Convention, which in turn was to elect Virginia’s delegates to the First Continental Congress. He became ill and could not attend the meeting, but he forwarded a paper that presented his views of the crisis. The paper was soon published as A Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774). Jefferson argued that the British Parliament had no control over the American Colonies, and that Parliament’s efforts to limit their economic and political liberties were illegal and unjust.

Jefferson attended the Second Virginia Convention in the spring of 1775. The members of this convention chose Jefferson as one of the delegates to the Second Continental Congress.

The Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson took a leading role in the Continental Congress. After the first major battles of the Revolutionary War, he was asked to draft a “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking up Arms.” However, the Congress found Jefferson’s declaration “too strong.” The more moderate John Dickinson drafted a substitute, which included much of Jefferson’s original version.

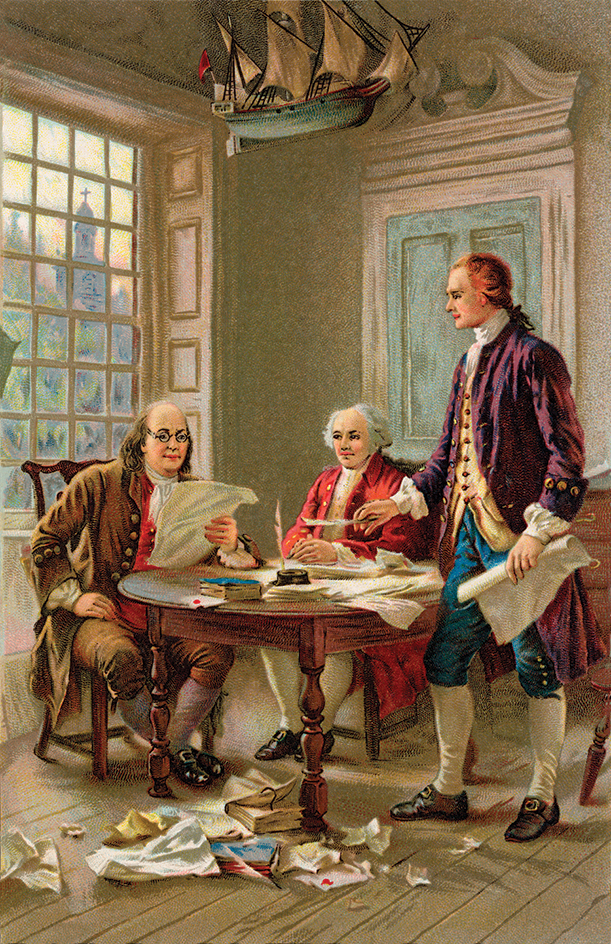

During the spring of 1776, sentiment rapidly grew stronger in favor of seeking independence from Britain. On June 7, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution stating that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.” The Congress appointed a committee to draw up a declaration of independence. On the committee were Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. The committee unanimously asked Jefferson to prepare the draft and approved it with few changes. On July 2, Congress as a whole approved Lee’s resolution and began reviewing the draft declaration. The lawmakers made certain changes. For instance, a clause blaming the British government for slavery in America—because the king had not closed off the slave trade—was deleted. The Congress adopted the Declaration on July 4.

The Declaration of Independence remains Jefferson’s best-known work. It set forth with eloquence, supported by legal argument, the position of the American revolutionaries. It affirmed belief in the natural rights of all people. Few of the ideas were new. Jefferson said his object was “to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent … Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind …” For a description of the Declaration, see Declaration of Independence.

Before Jefferson began writing the Declaration, he had spent part of his time outside Congress meetings preparing a draft constitution for Virginia. Jefferson sent his draft to Virginia in mid-June, but lawmakers there were already revising another draft constitution. They added Jefferson’s preamble and several other points from his draft to the final text of the state constitution.

Virginia lawmaker.

In September 1776, Jefferson resigned from the Congress and returned to the Virginia House of Delegates. He had no interest in military life and did not fight in the Revolutionary War. He felt that he could be more useful in Virginia as a lawmaker.

Jefferson’s early legislative efforts in Virginia involved land distribution and social reform. He sponsored a bill abolishing entail, which requires property owners to leave their land to specified descendants, rather than disposing of it as they wish. Jefferson then succeeded in outlawing primogeniture, whereby all land passes to the eldest son. Without entail and primogeniture, great estates could be broken up. Jefferson described the purposes of land reform when he wrote: “instead of an aristocracy of wealth … to make an opening for the aristocracy of virtue and talent.” At this time in Virginia, only white men who owned land could vote. After large estates were broken up, more white men owned property, and the number who could vote increased. Another bill introduced by Jefferson provided that immigrants could become naturalized after living in Virginia for two years.

Even more important were Jefferson’s bills designed to assure religious toleration. Jefferson sought to abolish the special privileges of the Anglican Church, which had remained Virginia’s established church even after the colonies had declared independence. He believed that public funds should not be used to favor an established church over others. He thought that the best way to ensure that people were not forced to support religious institutions they did not believe in was to forbid the use of tax money to pay clergymen or support any churches. Jefferson’s proposals aroused hostility not only among Anglicans, but also among some members of other denominations, who feared that a separation of church and state would loosen all religious ties. Nonetheless, Jefferson’s proposals were eventually enacted. Virginia ended the Anglican Church’s position as a state church in 1779. It took the church’s clergy off the public payroll and exempted Virginians from paying taxes to support the church. In 1786, when Jefferson was in France, lawmakers passed his Statute of Religious Freedom, which guaranteed religious liberty in Virginia.

Jefferson also worked to revise Virginia’s legal system. He pushed through numerous reforms, especially in the areas of land law and criminal law. The legislature defeated his plan for a system of free public education with a state-supported university, but parts of the plan later became law.

Governor.

The Virginia Assembly elected Jefferson governor for one-year terms in 1779 and 1780. During his administration, the state suffered severely from the effects of the Revolutionary War. At the request of General George Washington, Jefferson had redeployed (changed the position of) Virginia’s defenses to aid the Continental Army. Among those who recruited Virginians for military service was James Monroe, who at that time was a lieutenant colonel in the Army. Jefferson and Monroe formed a lasting friendship.

British troops under Benedict Arnold and Lord Cornwallis invaded Virginia in 1781. Because almost all of Virginia’s troops had been redeployed the previous year, the state could put up little resistance. Jefferson himself barely escaped capture on June 4 when troops led by Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton swept down on Monticello.

Jefferson’s term had ended on June 2. The Virginia legislature chose Thomas Nelson, Jr., the top officer of the state militia, to succeed Jefferson as governor. Jefferson was criticized for the state’s lack of resistance against the British invasion. An official investigation later cleared him of blame, but many years passed before Jefferson regained prestige in his home state. The criticism wounded him deeply, and he left public office with genuine relief.

Delegate to the Congress.

Jefferson returned to Monticello embittered and determined to give up public life forever. In response to questions he had received from a French diplomat, Jefferson began writing what would become his only published book, Notes on the State of Virginia (1784-1785). The book included much information on Virginia’s geography, history, legal system, and population, in addition to statements by Jefferson about politics, science, and race. It was in Notes on the State of Virginia that Jefferson called for an end to the institution of slavery. However, he also argued that Black people were biologically inferior to white people.

The death of Jefferson’s wife, Martha, in September 1782 left him stunned and distraught. For several months, he spoke to few people and wrote to none. In 1783, Jefferson was selected to serve, once again, as one of Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress. He accepted the office because he felt it would take his mind off his personal sorrows. During his year in the Congress, he served as chairman of several committees and devised a decimal system of currency. Most important was Jefferson’s work on the Ordinance of 1784 and the Land Ordinance of 1785. These measures formed the basis for later American land policies.

The problem of western lands had troubled the colonies from the beginning of the American Revolution. Several colonies claimed land west of the Appalachian Mountains. Virginia, under Jefferson’s leadership, gave up its claims to the area in 1784. Other states followed, and the region north of the Ohio River and west of Pennsylvania became the first American territory, the Northwest Territory. Problems of how to govern the area and how to use its land then arose. The Congress appointed two committees to consider the issues and made Jefferson chairman of both. In 1784, Jefferson submitted a draft of an ordinance for the political organization of the western lands. It would have divided the entire region into several states. Each state would eventually be admitted to the Union on a basis of complete equality with the original 13 states. Jefferson’s provision forbidding slavery west of the Appalachians lost by a single vote. The Ordinance of 1784 never went into effect, but it furnished the basis for the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which provided for the government of the Northwest Territory.

Minister to France.

In May 1784, the Congress sent Jefferson to France to join John Adams and Benjamin Franklin in negotiating European treaties of commerce. The next year, Franklin resigned as minister to France, and Jefferson succeeded him. The United States was suffering from a weak central authority under the Articles of Confederation, which served as the basic charter of the early U.S. government. Jefferson found himself troubled by what he described as “the nonpayment of our debts and the want of energy in our government.” Nonetheless, he did work out several important commercial agreements. Such agreements enabled American farmers to sell crops to foreign markets.

In 1789, the French Revolution began. French reformers regarded Jefferson as a champion of liberty because of his political writings and his legal reforms in Virginia. The Marquis de Lafayette, who had fought for American independence, and other moderates often sought Jefferson’s advice. Jefferson tried to keep out of French politics, but he did draft a proposed Charter of Rights to be presented to the king. This document and his other suggestions urged moderation because Jefferson felt that the French were not yet ready for a representative government of the American type. Jefferson hoped that the French would move from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy. Overall, he sympathized with the French Revolution, feeling it was similar in purpose to the American Revolution.

Jefferson had taken his daughter Martha to France with him, and Mary joined them in 1787. Both girls attended a convent school in Paris. Jefferson traveled widely in Europe. He broadened his knowledge of many subjects, especially architecture and farming. He applied for a leave in 1789 and sailed for home in October. He wanted to settle his affairs in America and take his daughters back home. Jefferson expected to return to represent the United States in France.

National statesman

During Jefferson’s stay in France, Americans at home had begun reorganizing the government. In 1787, statesmen assembled at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia and drew up the document that became the Constitution of the United States. Jefferson’s friend James Madison sent him a draft, which he approved. But Jefferson objected strongly to the lack of a bill of rights and wrote letters urging one. Soon after the Constitution went into effect, Madison introduced the 10 amendments that became the Bill of Rights.

Secretary of state.

Jefferson arrived in the United States in November 1789. A letter from President George Washington awaited him, asking Jefferson to be secretary of state in the new government. Jefferson received this invitation “with real regret,” but he finally yielded to Washington’s urging.

Jefferson and Hamilton.

Sharp differences of opinion soon arose between Jefferson and the secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton, though younger than Jefferson, had gained prominence as an associate of George Washington and a spokesman for the Constitution. Hamilton believed that the Constitution gave the majority of power to the central, or federal, government. Jefferson, however, interpreted the Constitution differently. He believed that, although the Constitution had granted many responsibilities to the federal government, the bulk of the decision-making authority belonged at the state level. Hamilton’s financial program brought these differences into the open.

Jefferson supported Hamilton’s plan for funding the debts of the previous American governments. He also agreed, reluctantly, that the new Congress should accept responsibility for the debts taken on by the states during the Revolutionary War. This proposal aroused considerable opposition, especially in Virginia and other Southern states that had already paid off much of their own debt. Such states did not want to pay the debts of other states. Some Southern members of Congress agreed to vote for paying the state debts in return for having the national capital in the South. Jefferson helped arrange this compromise, which led to the movement of the capital to its present location at Washington, D.C., on the Potomac River between Maryland and Virginia.

Key disagreements between Jefferson and Hamilton involved Hamilton’s plans to encourage commerce and manufacturing and to establish a national bank. Jefferson wanted the United States to remain chiefly committed to agriculture. He feared that a national bank would encourage financial speculation and hurt farming interests. Jefferson also thought it would give the government too much power. President Washington asked his Cabinet to submit opinions on the constitutionality of a national bank. Jefferson argued that the federal government should assume only the powers expressly given it by the Constitution, a theory later called “strict construction.” Hamilton responded with the notion of “loose construction,” claiming that the federal government could assume all powers not expressly denied it in the Constitution. Washington, who generally favored Hamilton in domestic affairs, approved the bank.

The differences between Jefferson and Hamilton grew into a bitter personal feud. Their conflicting points of view also led to the development of the first American political parties. The Federalists adopted Hamilton’s principles. Jefferson led the party that historians label the Democratic-Republicans. The Democratic-Republicans generally called themselves Republicans during Jefferson’s time, but the group was not connected to the modern Republican Party. In fact, historians regard the Democratic-Republicans as the early form of the group that became the Democratic Party in the late 1820’s and the 1830’s.

International relations.

Jefferson wanted the United States to build commercial and political relationships with as many European nations as possible. This, too, led to disagreements with Hamilton, who favored a close relationship with Britain. Jefferson urged recognition of the revolutionary government of France. But as the French Revolution grew more radical, he reluctantly supported Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation, which called for “conduct friendly and impartial” to France and other European nations. Jefferson agreed on demanding the recall of Edmond Genet, a controversial minister from France.

Jefferson supported Washington’s policy of acquiring the lands of Indigenous (native) American groups through treaty. Indigenous Americans have also been called American Indians or Native Americans. Jefferson also tried to persuade the British to abandon their forts in the Northwest Territory and worked for free navigation of the Mississippi river. For a fuller description of this period, see Washington, George.

Vice president.

Jefferson joined his fellow Cabinet members in urging Washington to accept a second term as president, which began in 1793. But Jefferson, frustrated over losing Cabinet disputes to Hamilton, resigned as secretary of state at the end of that year. Jefferson spoke publicly about remaining retired from politics, but this talk did not last long.

In 1796, Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican supporters nominated him as a candidate for president. He ran against John Adams, the Federalist candidate, in the first party contest for the American presidency. Adams received 71 electoral votes and was elected president. Jefferson received 68 electoral votes, the second largest number. By the law of the time, he became vice president.

Jefferson took no active part in the new administration because it was largely Federalist. Because the vice president also serves as president of the Senate, Jefferson observed legislative debates but could not participate in them. He compiled A Manual of Parliamentary Practice (1801), a document of Senate procedures that still forms part of the basis for rules of procedure in both houses of Congress. During his time as vice president, Jefferson worked behind the scenes to strengthen the Democratic-Republican Party. He found strong support among small farmers, frontier settlers, and Northern laborers. Also during this time, he served as president of the American Philosophical Society.

In 1798, a diplomatic dispute known as the XYZ Affair aroused great hostility to France (see XYZ Affair). Concerns of a possible war with France led the Federalists to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws made it a crime for anyone to criticize the president or Congress. In effect, they deprived the Democratic-Republicans of freedom of speech and of the press. The laws aroused much opposition, and Jefferson led the attack against them.

Jefferson prepared a series of resolutions that were passed by the Kentucky legislature, and his friend James Madison prepared similar resolutions for Virginia. These Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions set forth the “compact” theory of the Union—the idea that the Union was a compact (agreement) among the states—and asserted the right of the states to judge when the compact had been broken. The resolutions were later used by advocates of nullification, who claimed that each U.S. state had a right to nullify (reject) national laws.

Election of 1800.

The Democratic-Republicans again nominated Jefferson for president in 1800, and they named former Senator Aaron Burr of New York for vice president. The Federalist Party renominated President Adams and chose diplomat Charles C. Pinckney of South Carolina as his running mate.

The Federalists claimed that Jefferson was a revolutionary, an anarchist, and an atheist. However, the Federalists were divided among themselves, because a quarrel between Adams and Hamilton had divided Federalist voting blocs (groups with common interests). In addition, the unpopular Alien and Sedition Acts persuaded many voters to switch party allegiances, bringing about Democratic-Republican gains at the state and national levels.

Between the presidential candidates, Jefferson received 73 electoral votes to 65 for Adams. At the time, however, electors did not distinguish between votes for president and vice president, and each Democratic-Republican elector had cast one vote for Jefferson and the other for Burr. As a result, Jefferson and Burr tied, and the decision moved to the House of Representatives.

The House at that time was still controlled by the Federalists, because the newly elected Democratic-Republican Congress had not yet taken office. Many Federalists did not want to give the presidency to Jefferson. Some considered schemes that would have kept a Federalist as president or that would have made Burr president. However, when it became obvious that the selection of a Federalist president would not stand, many saw Jefferson as the more reasonable alternative. Hamilton—who trusted Burr even less than he did Jefferson—threw his influence to the support of Jefferson, and Jefferson won election on the 36th ballot. The final vote occurred on Feb. 17, 1801. Burr became vice president.

The election of 1800 led to an amendment to the Constitution. Under Amendment 12, electors in the Electoral College vote for one person as president and for another as vice president.

Jefferson’s first administration (1801-1805)

The first term of Jefferson’s presidency was a time of growth and prosperity. The United States was at peace with the United Kingdom, France, and Spain, as well as with Indigenous American groups. The United States increased greatly in size, and its economy expanded.

Loading the player...Thomas Jefferson's inaugural address

Life in the White House.

The so-called “President’s House” was only partly built when Jefferson moved in. He felt somewhat lonely in what he described as “a great stone house, big enough for two emperors, one pope and the grand lama.” Jefferson’s wife had been dead 181/2 years when he became president. The White House’s most popular hostess at this time was Dolley Madison, the wife of James Madison, who had become secretary of state. Jefferson’s daughter Martha Randolph also served as hostess from time to time. Jefferson’s grandson, James Randolph, was the first child born in the White House.

Jefferson kept a French steward and chef, but he tried to eliminate some of the formality in White House protocol. He began the practice of having guests shake hands with the president instead of bowing. He also placed dinner guests at a round table so that everyone would feel equally important. Always interested in architecture, Jefferson developed some ideas for the addition of east and west terraces and a north portico to the White House. He employed the English-born architect Benjamin H. Latrobe to carry out these ideas.

New policies.

Jefferson believed that the federal government should play a limited role in citizen’s lives. With the help of his secretary of the treasury, Albert Gallatin, he strictly managed government programs and spending. Under Jefferson’s leadership, the federal government sharply cut expenditures for the Army and Navy. At the same time, however, Jefferson oversaw the founding of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. The federal government under Jefferson also made substantial payments on the national debt and repealed excise taxes (taxes on specific products or services). Excise taxes had aroused opposition under the Federalists.

Jefferson’s administration also reversed other Federalist policies, particularly the laws that made up the Alien and Sedition Acts. The government repealed the Naturalization Act, and the Alien Friends Act and the Sedition Act were not renewed. The Alien Enemies Act was greatly amended.

Jefferson believed that appointments to federal government jobs should be based on merit. But Federalists held all the offices, and he quickly discovered that vacancies “by death are few; by resignation none.” He removed some Federalists, and generally appointed Democratic-Republicans to fill the vacancies. By the end of Jefferson’s second term, his party held most federal offices. Jefferson’s actions foreshadowed the spoils system, the practice of giving appointments to public office as political rewards for party service.

The courts.

Jefferson’s administration asked Congress to repeal the Judiciary Act of 1801. This act had allowed President Adams to make more than 200 “midnight appointments” of judges and other court officials just before he left office. Some of these judges had no commissions, no duties, and no salaries. Jefferson told the judges to consider their appointments as never having been made.

William Marbury was a justice of the peace whom Adams had appointed to a five-year term in the District of Columbia. When Secretary of State James Madison withheld his appointment, Marbury asked the Supreme Court, under Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, to force Madison to grant the appointment. Marbury’s action led to Marbury v. Madison (1803), one of the most important Supreme Court decisions in U.S. history. In its decision, the court declared that Section 13 gave the Supreme Court powers not provided by the Constitution and was therefore unconstitutional. The court’s decision, written by Chief Justice John Marshall, thus established the power of judicial review—the court’s authority to declare laws unconstitutional. The court refused to force Madison to deliver Marbury’s commission. See Marbury v. Madison.

On the surface, the decision was a victory for Jefferson and his Democratic-Republicans, because the administration did not have to deliver commissions to the “midnight judges” appointed by Adams. However, the Democratic-Republicans were disturbed by the idea that the Supreme Court could declare unconstitutional a law passed by Congress. This principle placed a powerful tool in the hands of the courts, which the Federalists still controlled. Many Democratic-Republicans feared that the Supreme Court would use its power to help the Federalists.

The Democratic-Republicans used the impeachment (removal) of judges as one way of checking the federal courts. First they impeached John Pickering, a New Hampshire judge who had reportedly become insane. After the Senate removed Pickering from office, the House brought impeachment charges against Justice Samuel Chase of the Supreme Court. The House charged that Chase had criticized the Jefferson administration unfairly. The Senate acquitted him, much to Jefferson’s disappointment. This series of events helped establish that political changes do not affect the tenure of judges.

War with Tripoli.

Ever since Jefferson had been minister to France, he had urged the United States to act against the corsairs (pirates) that were linked to North Africa‘s Barbary States (now part of Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia). The four Barbary States—Algiers, Morocco, Tunis, and Tripoli—had authorized corsairs to attack ships from other countries unless those countries gave an annual tribute (payment of money) to the states. The United States had negotiated treaties with all four of the Barbary States. However, in 1801, Tripoli opened war on American shipping because it wanted a greater amount of tribute money. The United States Navy blockaded Tripoli’s ports, bombarded fortresses, and eventually forced a resolution to the conflict. The war with Tripoli caused Jefferson to abandon his plan to put U.S. Navy ships in dry dock and to rely only on short-range gunboats for coastal defense.

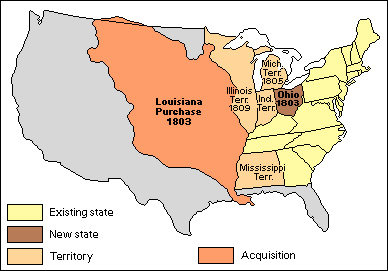

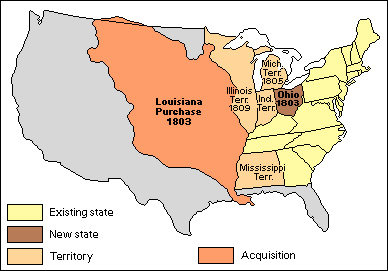

The Louisiana Purchase.

The Louisiana Territory, a vast region between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, had been transferred from France to Spain in 1762. In 1801, Jefferson learned that Spain planned to cede (hand over) the area back to France. Spanish control of Louisiana had posed no threat to the United States. However, Jefferson had concerns about France gaining the territory. He feared that the French government, under Napoleon I, might restrict commerce through New Orleans or try to establish new French colonies on the Mississippi.

In January 1803, Jefferson obtained $2 million from Congress for “extraordinary expenses.” He sent James Monroe to Paris to help the American minister, Robert Livingston, negotiate with France. Jefferson hoped to buy New Orleans and the Floridas (with West Florida at the time extending to the Mississippi). He at least wanted to get a guarantee of free navigation of the Mississippi and various commercial privileges at New Orleans.

Before Monroe reached Paris in April, Livingston proposed a modest purchase of New Orleans. Talleyrand, the French foreign minister, astounded Livingston by asking what the United States would give for the whole of Louisiana. After Monroe arrived, he and Livingston quickly struck a bargain. They agreed to pay 60 million francs and give up American claims against France—making a total price of about $15 million. The deal enabled the government to gain control of the Mississippi River and almost double the nation’s size.

Jefferson was uncertain whether the government had a right under the Constitution to add this vast new territory to the Union. But his doubts did not keep him from submitting the treaty to the Senate, which ratified it by a vote of 24 to 7 in October 1803.

Exploration and expansion.

In January 1803, Jefferson secretly petitioned Congress to authorize an exploration through the Louisiana Territory and the Oregon region. He hoped that the expedition would find a route to the Pacific Ocean along the Missouri and Columbia rivers. Congress authorized the expedition, and Jefferson chose Meriwether Lewis, a U.S. Army captain and Jefferson’s private secretary, to lead it. Lewis selected William Clark, a former Army officer, to join him. Between 1804 and 1806, Lewis, Clark, and their companions traveled from a camp near St. Louis to the headwaters of the Missouri River, across the Rockies to the Pacific, and finally back to St. Louis. They returned with maps of their route and the surrounding areas, descriptions of plant and animal life and natural resources, and information about America’s Indigenous cultures.

The population of the Northwest Territory grew rapidly during Jefferson’s first administration. Ohio joined the Union in 1803 as the 17th state. In 1804, the government encouraged western settlement by cutting in half—from 320 to 160 acres (130 to 65 hectares)—the minimum number of acres of western land that could be bought. Anyone with $80 in cash could make the first payment on a frontier farm.

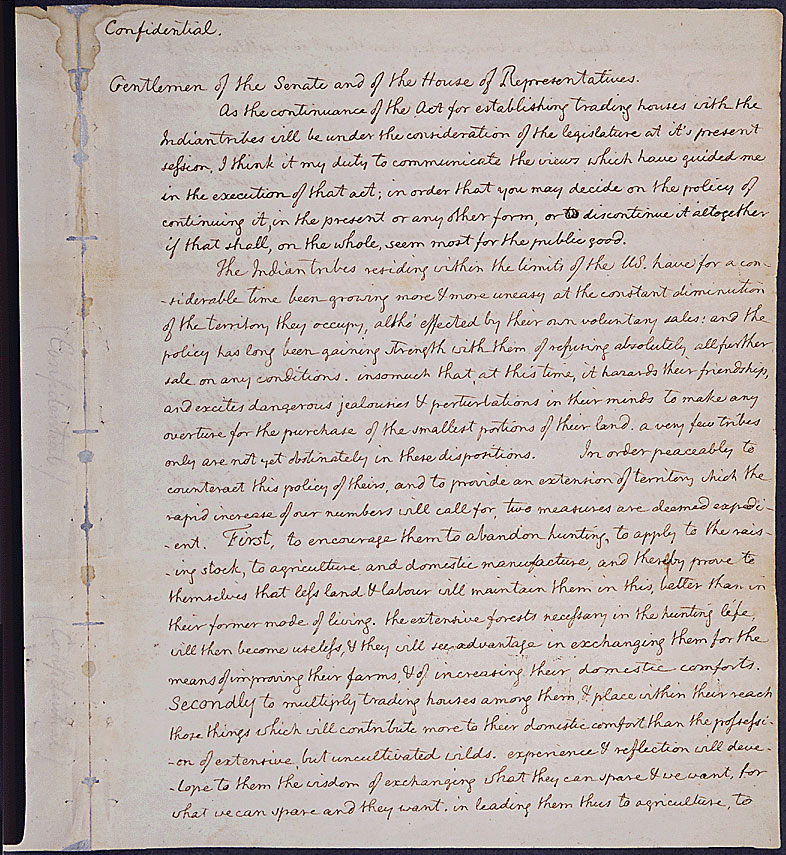

Policies toward Indigenous Americans.

Jefferson studied accounts of Indigenous American cultures in great detail and collected information about Indigenous languages. As president, he continued the policies toward Indigenous Americans that George Washington and John Adams had pursued. Jefferson’s agents were instructed to encourage trade with Indigenous American leaders and communities. The administration hoped that commerce would make Indigenous ways of life more similar to those of European Americans. If Indigenous people became more “civilized,” Jefferson reasoned, they would be more likely to become settled farmers and sell extra traditional hunting lands to the government. Jefferson also proposed the idea that Indigenous groups could be relocated to the area west of the Mississippi River.

Indigenous groups differed in their reactions to such “civilization” plans. Some members of groups like the Cherokee and Muscogee, or Creek, adopted European ways, including plantation agriculture and slavery. Other groups, such as the Shawnee, resisted. The Shawnee leader Tecumseh defended Indigenous culture and organized resistance to the white settlers.

Election of 1804.

Jefferson ran for reelection in 1804. But Vice President Aaron Burr was left off the ballot because he had become a notorious figure after killing Alexander Hamilton in a duel in July 1804. The Democratic-Republicans nominated Governor George Clinton of New York for vice president. The final electoral count gave 162 votes to Jefferson and only 14 to the Federalist candidate, Charles C. Pinckney.

Jefferson’s second administration (1805-1809)

Jefferson’s second term as president began, as he later put it, “without a cloud on the horizon.” However, his second term became more troubled than his first, as conflict overseas nearly pushed the nation into war.

The Burr conspiracy.

After leaving the office of vice president, Aaron Burr became involved in a scheme to create a new independent state in the lower Mississippi Valley. Historians believe that he planned to create the state by breaking Western lands away from the United States, invading Spanish territory, or both. The details of the scheme remain unclear and have been debated by historians.

Burr was unable to gain support from the British, French, or Spanish, but he did raise a small military force of his own. In 1806, Burr set off down the Ohio River for New Orleans, hoping to gather recruits along the way. General James Wilkinson, the governor of the Louisiana Territory, had encouraged Burr to expect his support. However, Wilkinson exposed Burr’s plot and wrote to Jefferson about a “deep, dark, wicked, and widespread conspiracy.”

Jefferson had Burr captured and taken to Richmond, Virginia, where he was tried for treason. However, Chief Justice John Marshall presided over the trial and interpreted the charge of treason so narrowly that the jury had to acquit Burr.

The struggle for neutrality.

War had broken out between the United Kingdom and Napoleon’s France in May 1803. As fighting continued, Jefferson found that his chief tasks were to keep the United States out of the war and to uphold the country’s rights as a neutral.

The United Kingdom and France were destroying each other’s merchant shipping. As a result, a large part of the trade between Europe and the Caribbean fell into American hands. American shipbuilding and commerce grew rapidly, and thousands of sailors were needed. Most of these sailors came from New England, but many had deserted from British ships. The United Kingdom, desperately needing seamen, began stopping American ships on the high seas and removing sailors suspected of being British. But because it was hard to tell British and Americans apart, thousands of Americans were seized and forced into the British Navy.

The struggle in Europe soon became so intense that both sides ignored the rights of neutral nations. In the Berlin and Milan decrees of 1806 and 1807, Napoleon announced his intention to seize all neutral ships bound to or from a British port. The British issued a series of Orders in Council (government decrees) that blockaded all ports in the possession of France or its allies. In practice, this meant that the British would try to seize any ship bound for the European continent, while the French would attempt to seize ships sailing almost anywhere else.

In June 1807, the British warship Leopard launched an unprovoked attack on the American ship Chesapeake. The Leopard fired on the Chesapeake after the captain of the American vessel refused to let the British search his ship for deserters. The incident threatened to bring the two nations to war.

The embargo.

Jefferson felt that he could bring the United Kingdom and France to reason by closing American markets to them, and not selling them any American supplies. In 1807, he sent the Embargo Act to Congress, and it quickly passed. The law prohibited exports from the United States and barred American ships from sailing into foreign ports.

In practice, however, the embargo affected the United States far more than it did either the United Kingdom or France. Ships lay idle, sailors and shipbuilders lost their jobs, and exports piled up in warehouses. Many Americans evaded the law, and smuggling flourished.

The government had to pass additional laws to increase the nation’s coastal defenses and to enforce the embargo. After 14 months, it became clear that the embargo would force no concessions from either the United Kingdom or France. Public clamor against the measure grew overwhelming, and Congress repealed it in March 1809 by passing the milder Non-Intercourse Act.

Many people urged Jefferson to run for reelection again in 1808. Jefferson, however, chose to follow George Washington’s example and retired at the conclusion of his second term. After James Madison became the fourth president of the United States in March 1809, Jefferson returned to Monticello.

Later years

Jefferson was 65 when he retired from the presidency. In his later years, he divided his time between his plantations at Monticello and Poplar Forest. His major public activity during his retirement was guiding the creation of the University of Virginia.

The sage of Monticello.

In retirement, Jefferson turned to music, architecture, chemical experiments, and the study of religion, philosophy, law, and education. He also improved his flower and herb gardens and experimented with new crops and farming techniques.

Jefferson carried on correspondence with people in all parts of the world. He improved a copying device called the polygraph, which made file copies of the many letters he wrote. He entertained numerous guests who came to pay their respects. In 1811, Jefferson was reconciled with his political rival John Adams, and the two men renewed their old friendship. Their letters ranged widely over the fields of history, philosophy, politics, religion, and science. In 1815, Jefferson sold his personal library to Congress to replace books that had been destroyed when the British burned the U.S. Capitol during the War of 1812 (1812-1815).

Jefferson had withdrawn from politics, but he was often consulted on public affairs. Presidents Madison and Monroe, his successors in the White House, frequently sought his advice. Many of Jefferson’s friends urged him to speak out against slavery, but Jefferson claimed his views on the subject were well known. He never spoke publicly on slavery during his retirement.

Jefferson never recovered from the debt he inherited from his father-in-law. Though he sought to make his plantations as profitable as possible, he also spent a great deal of money. He made additions to Monticello, entertained lavishly, and supported members of his family. Public contributions aided Jefferson in his later years, but they did not solve his financial problems. After Jefferson’s death, much of his property, most of the people he held in slavery, and Monticello itself were sold by Jefferson’s heirs to pay his creditors.

University founder.

Jefferson’s most important contributions in his later years were in the field of education. As a young legislator, he had worked for the reform of Virginia’s system of public education. Later, he had tried to improve William and Mary College. In time, he became convinced that the state needed an entirely new university.

After he retired from politics, Jefferson worked to create the University of Virginia. He projected his character, interests, and talents into the planning of a university “based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind to explore and to expose every subject susceptible of its contemplation.” Jefferson organized the curriculum, hired the faculty, and selected the library books. He also drew the plans for the buildings and supervised their construction. As a result of his efforts, scholars from other countries came to teach at the university. In March 1825, Jefferson saw the University of Virginia open with 40 students.

On July 4, 1826, 50 years after the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson died. He was buried at Monticello, where an obelisk (stone monument) marked his grave. The inscription that Jefferson wrote for the obelisk reads: “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, Author of the Declaration of American Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom, & Father of the University of Virginia.” In 1883, descendants of Jefferson’s gave the original obelisk to the University of Missouri at Columbia in honor of the first state university to be founded within what had been the Louisiana Territory. A replica sits atop Jefferson’s grave at Monticello today.

Jefferson is one of four U.S. presidents honored at Mount Rushmore National Memorial, in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Mount Rushmore features the faces of Jefferson, George Washington, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln carved into a granite cliff. Work on the memorial began in 1927 and continued for more than 14 years. Jefferson is also honored on the U.S. nickel. Pictures of Jefferson and Monticello first appeared on the coin in 1938. The Jefferson Memorial stands at the edge of the Tidal Basin, near the National Mall, in Washington, D.C. The memorial, which was dedicated in 1943, contains a statue of Jefferson and quotations from his writings.