Kennedy, John Fitzgerald (1917-1963), was the youngest man ever elected president of the United States, and he was the youngest ever to die in office. He was shot to death on Nov. 22, 1963, after two years and 10 months as chief executive. The world mourned Kennedy’s death, and presidents, premiers, and members of royalty walked behind the casket at his funeral. Kennedy was succeeded as president by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Kennedy, a Democrat, won the presidency with his “New Frontier” program, after a series of television debates with his Republican opponent, Vice president Richard M. Nixon. At 43, Kennedy was the youngest man ever elected president. (Theodore Roosevelt was 42 when he became president upon the death of William McKinley. He was 46 when he was elected president.) Kennedy was the first president of the Roman Catholic faith. He also was the first president born in the 1900’s.

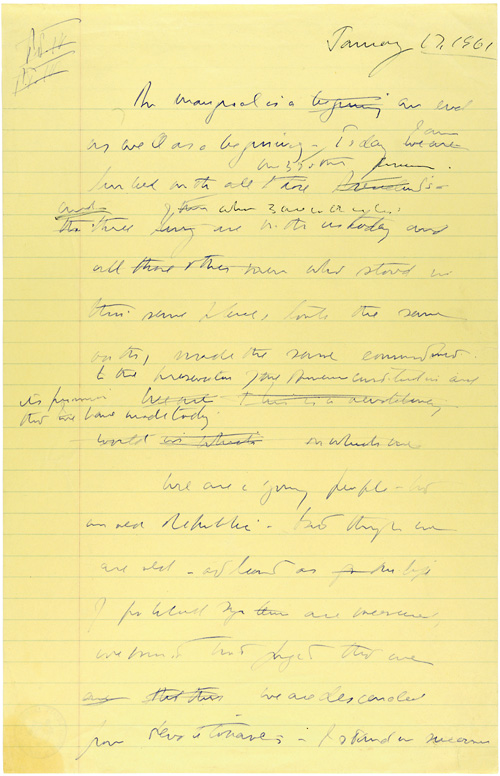

In his inaugural address, President Kennedy declared that “a new generation of Americans” had taken over leadership of the country. He said Americans would “… pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” He told Americans: “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

Kennedy became widely known by his initials, JFK. He won world respect as the leader of the Free World. He greatly increased U.S. prestige in 1962 when he turned aside the threat of an atomic war with the Soviet Union while carrying out negotiations that resulted in the Soviets withdrawing missiles from Communist Cuba. The Kennedy action marked the start of a period of “thaw” in the Cold War as relations grew friendlier with the Soviet Union. In 1963, the United States, the Soviet Union, and more than 100 other countries signed a treaty outlawing the testing of atomic bombs under water and on or above ground. On the home front, the United States enjoyed its greatest prosperity in history. African Americans’ demands for civil rights led to serious domestic conflicts, but African Americans made greater progress in their quest for equal rights than at any time since the Civil War. During Kennedy’s administration, the United States made its first piloted space flights and prepared to send astronauts to the moon.

Early life

Family background.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy was the second son of Joseph Patrick Kennedy (1888-1969) and Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy (1890-1995). The president’s ancestors were Irish farmers of Wexford County in southeastern Ireland. His great-grandfather, Patrick Kennedy, left Ireland during the great potato famine of the 1840’s and settled in Boston. The president’s grandfather, Patrick J. Kennedy, became a state senator and the political “boss” of a ward in Boston.

The president’s mother also came from a political family. Her father was John F. (“Honey Fitz”) Fitzgerald, a colorful politician. Fitzgerald served in the state senate and the United States House of Representatives. He also served as mayor of Boston for two terms.

Joseph P. Kennedy, the president’s father, was a self-made millionaire. During the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, he served as the first chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and as U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom.

Boyhood.

Kennedy was born on May 29, 1917, in Brookline, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb. The other eight Kennedy children were Joseph, Jr. (1915-1944), who was killed in World War II; Rosemary (1918-2005); Kathleen (1920-1948); Eunice (1921-2009); Patricia (1924-2006); Robert F. (1925-1968), who became attorney general under his brother and then served as U.S. senator from New York from 1965 until his assassination; Jean (1928-2020); and Edward M. “Ted” (1932-2009), who served as a U.S. senator from Massachusetts from 1962 until his death.

The Kennedys moved often, to bigger homes and better neighborhoods, as the family grew and as Joseph Kennedy became wealthier. From Brookline, they moved to Riverdale, New York, then Bronxville, New York, both New York City suburbs.

As the Kennedy children grew up, their parents encouraged them to develop their own talents and interests. Loyalty to one another was important to the Kennedys. But the children also developed a strong competitive spirit. Jack, as his family called him, and Joe, his older brother, were especially strong rivals. Jack was quiet and often shy, but he held his own in fights with Joe. The boys enjoyed playing touch football.

Education.

John Kennedy attended elementary schools in Brookline and Riverdale. In 1930, when he was 13 years old, his father sent him to the Canterbury School in New Milford, Connecticut. The next year, he transferred to Choate Academy in Wallingford, Connecticut. Kennedy was graduated from Choate in 1935 at the age of 18. His classmates voted him “most likely to succeed.”

Kennedy spent the summer of 1935 in England. He enrolled at Princeton University that fall, but he developed jaundice and left school after Christmas. He entered Harvard University in 1936. There he majored in government and international relations.

In 1939, Kennedy spent the spring and summer in Europe. Traveling from country to country, he interviewed politicians and statesmen. He sent his father detailed reports on their views of the crisis that soon led to World War II in September 1939. Back at Harvard, Kennedy tried to explain in his senior thesis why the United Kingdom had not been ready for war. His thesis, published as Why England Slept, became a best-selling book.

Kennedy was graduated cum laude in 1940. He then enrolled in the Stanford University graduate business school, but dropped out six months later. After taking a trip through South America, Kennedy enlisted as a seaman in the U.S. Navy.

War hero.

For a few months, Kennedy was stationed in Washington, D.C. He applied for sea duty following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Kennedy was assigned to a PT boat squadron late in 1942. After learning to command one of the small craft, he was commissioned as an ensign.

Kennedy’s PT boat was assigned to patrol duty off the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific. Shortly after midnight on Aug. 2, 1943, a Japanese destroyer cut his boat in two. Two of the crew were killed. Kennedy and the other 10 men clung all night to the wreckage of their boat. The next morning, Kennedy ordered his men to swim to a nearby island. Despite an injured back, he spent five hours towing one of the disabled crewmen to shore. Kennedy spent most of the next four days in the water, searching for help. On the fifth day, he persuaded friendly islanders on Cross Island to go for help. Kennedy’s crew was rescued on August 7. For his heroism and leadership, Kennedy received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal. For being wounded in combat, he was awarded the Purple Heart.

In December 1943, the Navy returned Lieutenant Kennedy to the United States. He was suffering from malaria and his injured back gave him great pain. After recovering, Kennedy spent the rest of his naval service as an instructor and in various military hospitals. He then had a short career as a newspaper reporter.

Career in Congress

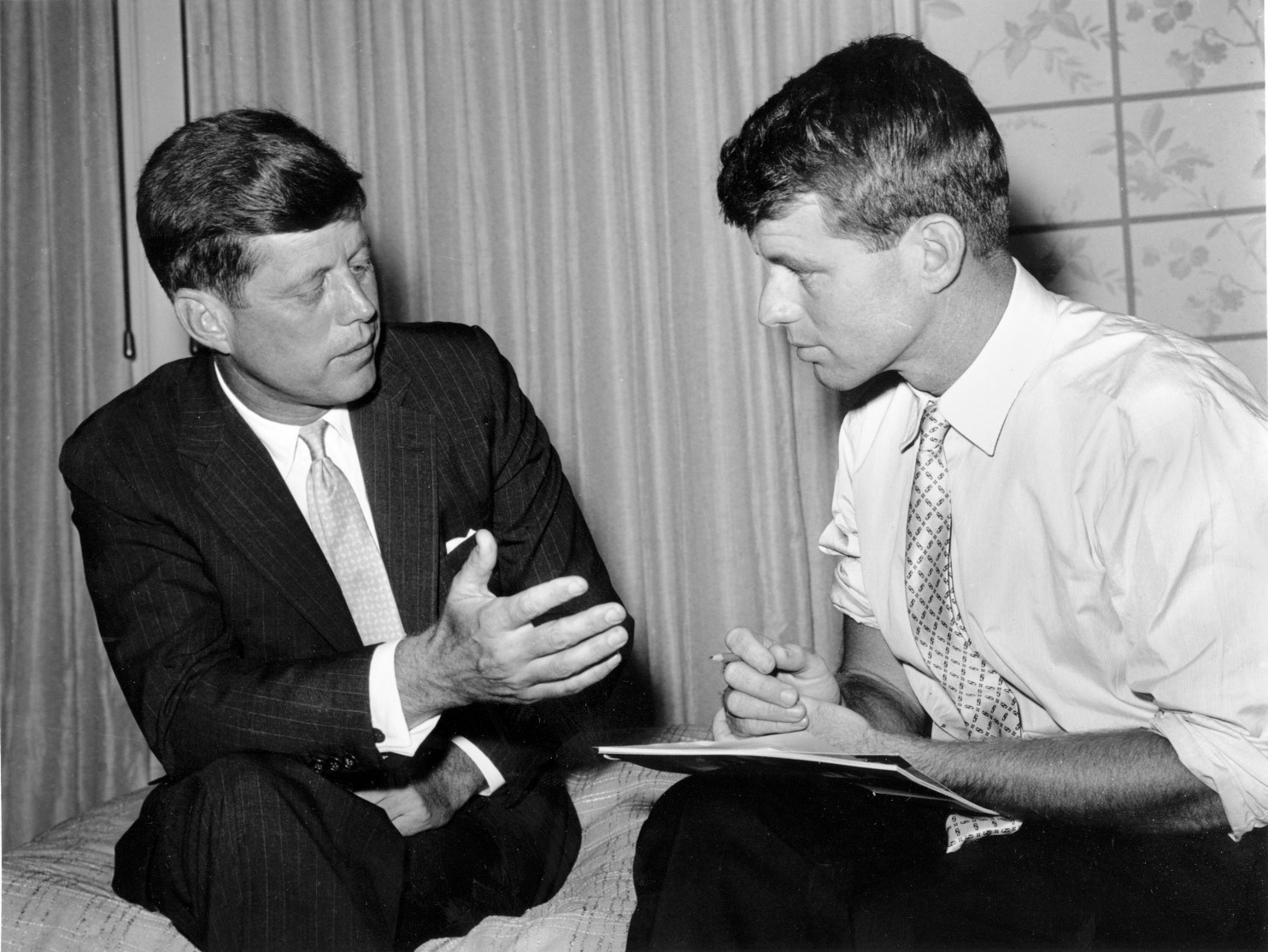

The Kennedys had thought Jack would become a writer or a teacher. His brother Joe was going to be the family politician. But Joe’s death in 1944 changed Jack’s future. Later, as a U.S. Senator, Kennedy said: “Just as I went into politics because Joe died, if anything happens to me tomorrow, my brother Bobby would run for my seat in the Senate. And if Bobby died, Teddy would take over for him.”

U.S. representative.

Kennedy began his political career in 1946. He ran for the U.S. House of Representatives. He opposed nine others for nomination in the solidly Democratic 11th Congressional District of Massachusetts. He won the nomination and went on to easily defeat his Republican opponent.

The 1946 campaign set a pattern that played a major part in Kennedy’s political success. His brothers and sisters helped him win the nomination. So did his mother. The women organized teas in the homes of voters. But his father was not active in Kennedy’s campaigns. His isolationism before World War II, his conservatism, and his wealth made him a controversial figure.

In January 1947, Kennedy took his seat in Congress. Later that year, he became seriously ill, and doctors discovered that he was suffering from a malfunction of the adrenal glands. To control the ailment, he had to take medicine daily for the rest of his life. But he kept that fact from public view. In Congress, Kennedy voted for most of the social welfare programs of President Harry S. Truman. He was reelected to the House in 1948 and 1950.

Campaign for the Senate.

In April 1952, Kennedy announced that he would oppose Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., a popular and experienced legislator, seemed certain to win reelection.

Kennedy’s mother and his brothers and sisters and their spouses joined him in the campaign. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Republican presidential candidate, carried Massachusetts in the 1952 election. But Kennedy upset Lodge by 70,637 votes.

Kennedy’s family.

In 1951, Kennedy met his future wife at a dinner party in Washington, D.C. Jacqueline “Jackie” Lee Bouvier (July 28, 1929-May 19, 1994) was the daughter of a wealthy Wall Street broker, John V. Bouvier III. She had attended Vassar College and the Sorbonne in Paris. When she met Kennedy, she was a student at George Washington University in Washington. Later, she worked as an inquiring photographer for the Washington Times-Herald. She and Kennedy were married on Sept. 12, 1953. A daughter was stillborn on Aug. 23, 1956, and was unnamed. Their daughter Caroline was born on Nov. 27, 1957. Their son John F., Jr., was born on Nov. 25, 1960. He was killed in an airplane crash in 1999. Another son, Patrick Bouvier, was born prematurely on Aug. 7, 1963. He died on Aug. 9, 1963. Five years after Kennedy’s death, Mrs. Kennedy married Aristotle Onassis, a Greek millionaire.

Senator Kennedy

focused at first on helping industries in Massachusetts and New England. He sponsored bills to help such industries as fishing, textile manufacturing, and watchmaking. Kennedy served on the Senate Labor Committee, and the Government Operations Committee, chaired by Senator Joseph R. McCarthy. Robert Kennedy, his brother, served on the Government Operations Committee staff as an assistant counsel.

At the time, McCarthy was the most controversial figure in American politics. Many persons praised him for his attacks on Communist influence in government. Others criticized McCarthy because they felt he had violated the civil liberties of persons investigated by his committee. Kennedy felt that McCarthy often abused his power and was endangering the honor of the Senate. Kennedy was ill when the Senate condemned McCarthy in 1954. But he said later that if he had been present, he would have voted for the condemnation.

During his first Senate term, Kennedy’s back caused him severe pain. In October 1954, and in February 1955, he underwent corrective surgery. While recovering, he wrote a book about some of the brave deeds of U.S. senators. For the book, Profiles in Courage, Kennedy was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for biography in 1957.

In 1957, Kennedy was appointed to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, a key assignment in Congress. He criticized the foreign policy of the Republican administration, and supported a program of increased aid to underdeveloped countries.

Kennedy also worked for moderate legislation to end alleged corruption in labor unions. He was a member of a Senate committee investigating racketeering in labor-management relations. Kennedy’s brother Robert was counsel for the committee. The Kennedys and other committee members engaged in dramatic arguments with controversial labor leaders, including James R. “Jimmy” Hoffa, of the Teamsters Union.

Bid for the vice presidency.

In June 1956, a movement to nominate Kennedy for vice president had gained strength among Democratic leaders. At the party’s national convention in Chicago, Kennedy made the presidential nominating speech for former Governor Adlai E. Stevenson of Illinois. The delegates chose Stevenson to oppose Eisenhower for the second time. Kennedy worked furiously for the vice presidential nomination. But he lost to Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee after a nip-and-tuck battle.

Election as president

Steps to the White House.

Kennedy began working for the 1960 presidential nomination right after the 1956 convention. He spent nearly every weekend campaigning. In 1958, Kennedy won reelection to the Senate by a majority of 874,608 votes.

Many Democratic leaders thought Kennedy had several disadvantages as a presidential candidate. His main drawback was his religion. Alfred E. Smith, the only Roman Catholic ever nominated for president by a major political party, had been badly defeated in 1928. Other possible shortcomings included Kennedy’s youth, his family wealth, and his relative inexperience in international affairs. Some Democrats opposed Kennedy because they thought he was too conservative and because he never actively opposed Senator McCarthy.

Kennedy decided that the key to the presidential nomination would be to win as many state primary elections as he could. He believed that victories in the primaries would prove he could win the presidency. Kennedy entered and won primaries in seven states.

At the Democratic national convention, Kennedy’s chief opponents for the presidential nomination were Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas, Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri, and Stevenson. Kennedy won on the first ballot. The delegates, at the request of Kennedy, nominated Johnson for vice president.

The Republicans chose Vice President Richard M. Nixon to oppose Kennedy for the presidency. Kennedy’s old opponent, Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., then U.S. delegate to the United Nations (UN) was Nixon’s running mate.

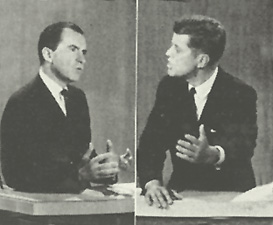

The 1960 campaign

was a hard-fought race. Both candidates were young, vigorous campaigners. At first, most experts believed Nixon would win. He had the advantage of being vice president under Eisenhower, an unusually popular president.

But Kennedy was not as unknown as some people believed. His good looks, wealth, and attractive wife had made him a popular subject for articles in newspapers and magazines. Television also helped Kennedy greatly during his four televised debates with Nixon. His poise helped answer criticism that he lacked the maturity needed for the presidency. The debates marked the first time that presidential candidates argued campaign issues face-to-face.

Nixon ran chiefly on the record of the Eisenhower administration. Kennedy promised to lead Americans to a “New Frontier.” He charged that, under the Republicans, the United States had lost ground to the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

Kennedy defeated Nixon by fewer than 115,000 popular votes. But he won a clear majority of votes in the Electoral College. Kennedy received 303 electoral votes to 219 for Nixon. Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia received 15 electoral votes.

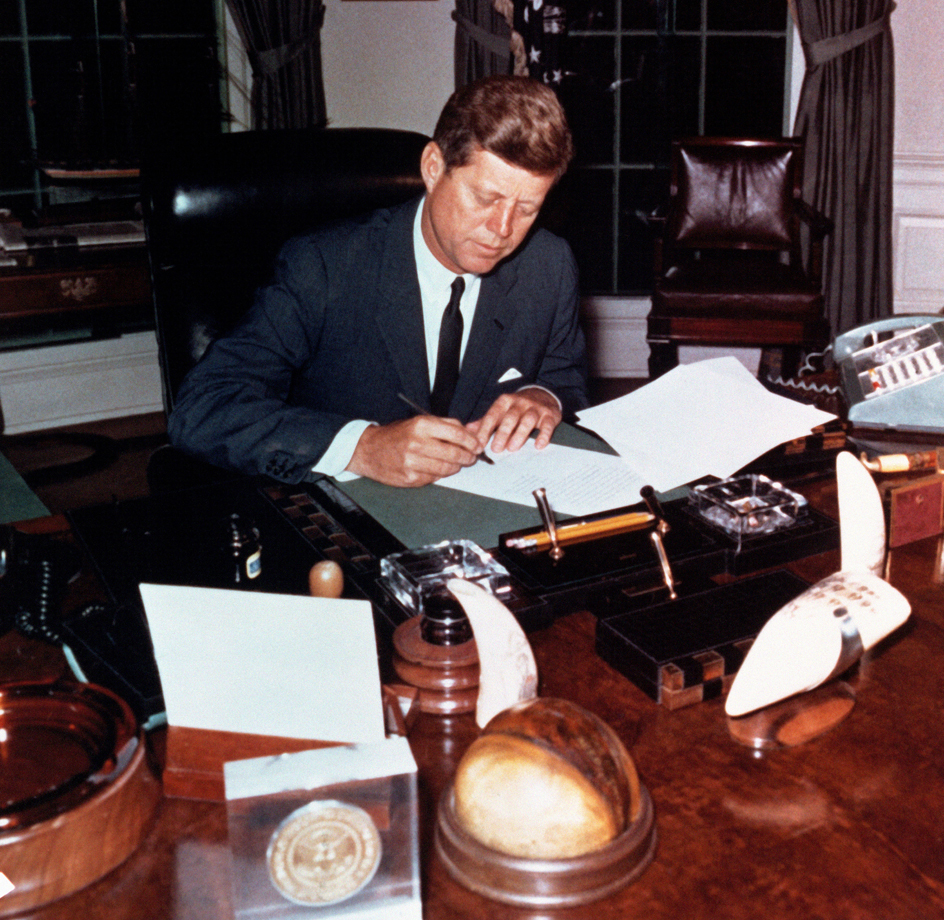

Kennedy was inaugurated president on Jan. 20, 1961. As he took charge of the federal government, he faced such internal problems as increased racial tensions, unemployment, and a sluggish economy. In foreign affairs, he faced the continuing spread of Communist influence, and the threat of nuclear war.

The national scene

The New Frontier,

the name Kennedy gave to his program, got off to a slow start. But the 87th Congress finally began passing measures sponsored by the administration. In April 1961, the legislators approved aid to economically depressed areas. In May, Congress approved an increase in the minimum hourly wage from $1 to $1.25. In September 1962, Congress passed Kennedy’s Trade Expansion Act. The act gave the president wide powers to cut tariffs so the United States could trade freely with the European Economic Community (now part of the European Union).

Loading the player...John Fitzgerald Kennedy's inaugural speech

One of the most successful of Kennedy’s programs was the U.S. Peace Corps. It was launched by executive order in March 1961, and was later authorized by Congress. The corps sent thousands of Americans abroad to help people in developing nations raise their standards of living. The Peace Corps seemed to carry the enthusiasm of the president to the people of other countries, who often called it “Kennedy’s Corps.”

Loading the player...Inaugural festivities for John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Kennedy also met major legislative defeats. Congress rejected a cabinet-level Department of Urban Affairs and Kennedy’s plan for medical care for the aged. Both measures later passed during Johnson’s presidency. Kennedy’s farm proposals faced resistance as well.

Kennedy reorganized the nation’s defense policies by increasing conventional weapons. He wanted to be prepared for nonnuclear wars and to make every effort to avoid using nuclear weapons.

Loading the player...John Kennedy on going to the moon

Business and labor.

In March 1962, the major steel producers signed a contract with the steelworkers union that increased workers’ benefits, but not their wages. Kennedy praised the contract, which he said would help prevent inflation. On April 10, the United States Steel Corporation led a move to raise steel prices $6 a ton. Kennedy angrily denounced the move as needlessly causing inflation, and the companies canceled it.

In May, prices on the New York Stock Exchange made their sharpest drop since 1929. Many people blamed the Kennedy administration. They felt the president’s action toward the steel companies reflected an antibusiness attitude. The president tried to answer these charges in a speech. He said there are three great ideas, or “myths,” in our domestic affairs that may prevent effective action: (1) that the federal debt is too large; (2) that the federal government is too big; and (3) that business cannot place its confidence in his administration.

Kennedy aided business by increasing tax benefits for companies investing in new equipment. In 1963, he proposed a $10-billion tax cut, which included lowering corporate taxes. He thought that the public would be able to spend more if taxes were cut. The increased spending would generate new business, and the taxes received from an expanded economy would more than offset the revenue lost in the tax cut.

Civil rights.

Demands for equal rights for African Americans became the major domestic issue during the Kennedy administration. In 1961, a group of nonviolent freedom riders, made up of Black and white demonstrators, entered Montgomery, Alabama, by bus to test local segregation laws. White rioters attacked them, and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy sent U.S. marshals to the city to help restore order. In 1962, James Meredith became the first Black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi, despite much opposition. Two people were killed in the rioting that followed on the university campus at Oxford. The president ordered 3,000 federal troops to the area to restore order.

In 1963, demands by African Americans for equal civil and economic rights increased. Racial protests and demonstrations took place across the United States. In May 1963, rioting broke out in Birmingham, Alabama. In June, Kennedy federalized the Alabama National Guard to enforce the integration of the University of Alabama. Kennedy federalized the Guard again in September to ensure the integration of public schools in three Alabama cities. On Aug. 28, 1963, about 250,000 persons staged a Freedom March in Washington, D.C., to demonstrate their demands for equal rights for Black citizens.

To meet growing demands of African Americans, Kennedy asked Congress to pass legislation requiring hotels, motels, and restaurants to admit customers regardless of race. He also asked Congress to grant the attorney general authority to begin court suits to desegregate schools on behalf of private citizens unable to start legal action themselves. In requesting the sweeping civil rights legislation, the president said, “The time has come for the Congress of the United States to join with the executive and judicial branches in making it clear to all that race has no place in American life or law.”

Other developments.

Kennedy’s Democratic Party gained four seats in the Senate and lost only two seats in the House in the 1962 elections. This was only the third time in the 1900’s that the party in power increased its representation in Congress in a midterm election. In his second year in office, Kennedy appointed two justices of the Supreme Court. The first was Byron R. White, then Deputy Attorney General. The second was Secretary of Labor Arthur J. Goldberg.

Life in the White House.

The Kennedys brought youth and informality to the White House. Caroline and John, Jr., were the youngest children of a president to live in the White House in more than 60 years. Caroline’s antics and bright comments amused the nation.

Women in many countries copied Jacqueline Kennedy’s stylish clothes and hairdo. In 1961, Mrs. Kennedy flew to Europe with her husband. Wherever she went, huge crowds gathered. President Kennedy presented himself to a Paris luncheon by saying, “I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris. …” In March 1962, Mrs. Kennedy toured Pakistan and India without the president. Mrs. Kennedy won praise for her redecoration of the White House. She gathered furnishings of past presidents and made the mansion a historic showplace and a tourist attraction. See White House (Rebuilding and redecorating).

The president gave recognition to the creative arts by appointing a special adviser on the arts. Many artists were invited to the White House.

Foreign affairs

Cuba.

On April 17, 1961, Cuban rebels invaded their homeland to overthrow Fidel Castro, the Communist-supported dictator. The assault ended in disaster. President Kennedy accepted blame for the ill-fated invasion, which had been planned by the United States.

Another Cuban crisis erupted in October 1962, when the United States learned that the Soviet Union had installed missiles in Cuba capable of striking U.S. cities. Kennedy ordered the U.S. Navy to quarantine (blockade) Cuba. Navy ships were ordered to turn back ships delivering Soviet missiles to Cuba. Kennedy also called about 14,000 Air Force reservists to active duty.

For a week, war seemed likely. Then, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev ordered all Soviet offensive missiles removed. Kennedy then lifted the quarantine. For more details, see Cuban missile crisis.

Berlin.

In 1961, the Soviet Union threatened to give Communist East Germany control over the West’s air and land supply routes to Berlin. The threat was part of a Soviet effort to end the combined American, British, French, and Soviet control of Berlin, begun in 1945, when World War II ended. The Western nations opposed any threat to the freedom of West Berlin.

In June 1961, Kennedy discussed Berlin with Khrushchev at a two-day meeting in Vienna, Austria. Nothing was settled, and the crisis deepened. Both countries increased their military strength. In August, the East Germans built a wall between East and West Berlin to prevent persons from fleeing to the West. Kennedy called up about 145,000 members of the National Guard and reservists to strengthen U.S. military defense. They were released about 10 months later. Loading the player...

John Kennedy in Berlin

Other developments.

In 1961, the United States established the Alliance for Progress, a 10-year program of aid for Latin American countries that agreed to begin democratic reforms. Kennedy hoped this program would bring social and political reform as well as fight poverty.

In 1961, Kennedy was interviewed by Khrushchev’s son-in-law, then editor of Izvestia, the Soviet government newspaper. Izvestia printed the entire interview.

In 1962, Congress approved a plan to purchase up to $100 million worth of bonds to help finance the UN.

The western Atlantic alliance remained strong, but Kennedy had trouble establishing a united NATO nuclear force. President Charles de Gaulle refused to commit France to the NATO nuclear force. He preferred an independent role for his country. Kennedy made a 10-day tour of Europe in the summer of 1963. He visited West Germany, Italy, Ireland, and the United Kingdom.

Southeast Asia continued to be a trouble spot. Kennedy ordered U.S. military advisers to the area in 1961 and 1962 when the Communists threatened South Vietnam and Thailand. Kennedy also sent advisers to Laos. In the summer and autumn of 1963, the United States severely criticized the South Vietnamese government headed by Ngo Dinh Diem for its repressive policies against the country’s Buddhists. The government imprisoned many Buddhist leaders and students who were leading demonstrations against the Diem government. Kennedy sent former Republican senator and vice presidential candidate Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., to South Vietnam as ambassador in 1963.

Arms control.

In September 1961, the Soviets resumed testing atomic weapons. The tests broke an unofficial test ban that had lasted nearly three years. The United States began testing shortly after the Soviets resumed their tests, but the United States conducted its tests underground, which created no dangerous fallout. But in April 1962, the United States resumed testing in the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean.

In July 1963, the Soviet Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom signed a treaty banning atomic testing in the atmosphere, outer space, and under water. Testing was permitted underground. Many countries that had no atomic weapons also signed the treaty.

Kennedy’s assassination

John F. Kennedy was shot to death by an assassin on Nov. 22, 1963, as he rode through the streets of Dallas. The death of the youthful and energetic president united Americans in shock, confusion, and despair.

Kennedy was succeeded by his vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson was the first Southerner to become president since Andrew Johnson succeeded Lincoln when Lincoln was assassinated in 1865.

The death of the president.

Kennedy came to Texas accompanied by his wife and Vice President and Mrs. Lyndon B. Johnson. The chief purpose of his trip was to heal a split in the Texas Democratic Party before the 1964 presidential campaign in which Kennedy planned to run for a second term. The Kennedy party left Washington, D.C., on Thursday, November 21, and flew to San Antonio, Houston, and Fort Worth. At 11:37 a.m. the next day, the president’s plane arrived in Dallas after a short trip from Fort Worth.

Plans called for the president, Mrs. Kennedy, Johnson, and others to travel in a motorcade through the streets of Dallas to the Dallas Trade Mart. Kennedy was scheduled to speak there at a luncheon. After leaving the plane, Kennedy entered an open limousine for the trip to the Trade Mart. The president sat in the rear seat on the right side of the car. His wife, Jacqueline, sat on his left. Texas Governor John B. Connally sat in a “jump” seat in front of the president, and Mrs. Connally sat to her husband’s left.

Behind the president’s car was a limousine filled with Secret Service agents. Vice President and Mrs. Johnson rode in the third car, also accompanied by Secret Service men. Many other special security precautions had been taken. Dallas had a reputation as a center for people who strongly opposed Kennedy. But friendly, cheering crowds lined the streets.

At 12:30 p.m., the cars approached an expressway for the last leg of the trip. Suddenly, three shots rang out and the president slumped down, hit in the neck and head. Connally received a bullet in the back. Mrs. Kennedy held her stricken husband’s head in her lap as the limousine raced to nearby Parkland Hospital.

Doctors worked desperately to save the president, but he died at 1:00 p.m. without regaining consciousness. Doctors said that Kennedy had no chance to survive when brought into the hospital. Governor Connally, although seriously wounded, later recovered.

The new president.

Television and radio flashed the news of the shooting to a shocked world. Vice President Johnson raced to the hospital and remained until Kennedy died. Then, he went to the airport where the presidential plane waited. Mrs. Kennedy and the coffin holding her husband’s body arrived later. At 2:39 p.m., U.S. District Judge Sarah T. Hughes administered the oath of office to Johnson, who became the 36th president of the United States. As Johnson took the oath in the airplane, he was flanked by his wife and by Mrs. Kennedy.

Then the plane carrying the new chief executive and his wife, the body of the dead president, and the late president’s widow returned to Washington. When the plane arrived, Johnson told the nation: “This is a sad time for all people. We have suffered a loss that cannot be weighed. …”

The death of Oswald.

Witnesses said the shots that killed the president came from a sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository, a building along the route of the motorcade. Police raced into the building but could not find the killer. Then they began a search for a building employee who had left the scene a few minutes after the shooting. About 1:15 p.m., the employee, Lee Harvey Oswald, is said to have shot and killed a Dallas policeman, J. D. Tippit, while resisting arrest.

Oswald was finally arrested in a theater a short while later, and was charged with the murders of President Kennedy and Tippit. Oswald had been given a hardship discharge from the U.S. Marines and had once tried to become a Soviet citizen. An admitted Marxist, Oswald had a Soviet wife. He also had been active in the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, a group that supported Cuba’s Communist dictator Fidel Castro.

The police questioned Oswald for two days, but he denied both murders. Dallas police claimed that the evidence against Oswald was overwhelming. The murder weapon, an Italian rifle with a telescopic sight, was found hidden in the School Book Depository. The rifle had been purchased by Oswald from a mail-order firm for $12.78. Oswald’s palm prints were found on the weapon.

On Sunday, November 24, two days after the assassination, Oswald was scheduled to be taken from the Dallas city jail to the county jail. As he was being led to an armored car for the trip, a Dallas nightclub owner, Jack Ruby (or Rubinstein), stepped out of the crowd and shot Oswald to death. A nationwide television audience witnessed the shooting. Oswald was taken to the same hospital where the president died. He died at 1:07 p.m., 48 hours after Kennedy’s death. Jack Ruby was convicted of Oswald’s murder in 1964, but the conviction was overturned in 1966. Ruby died in 1967, awaiting a new trial.

The world mourns.

The sudden death of the young and vigorous American president shocked the world. Kennedy’s body was brought back to the White House and placed in the East Room for 24 hours. On the Sunday after the assassination, the president’s flag-draped coffin was carried to the Capitol Rotunda to lie in state. Throughout the day and night, hundreds of thousands of people filed past the guarded casket.

Representatives from over 90 countries attended the funeral on November 25. Among them were Irish President Eamon De Valera, French President Charles de Gaulle, Belgian King Baudouin, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, Philippine President Diosdado Macapagal, and West German President Heinrich Luebke.

Kennedy was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. At the close of the funeral service, Mrs. Kennedy lighted an “eternal flame” to burn over the president’s grave. When Mrs. Kennedy died in 1994, she was buried next to her late husband.

In one of his first acts, President Johnson named the National Aeronautics and Space Administration installation in Florida the John F. Kennedy Space Center. Other public buildings and geographical sites throughout the world were named for Kennedy. Congress voted funds for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. The United Kingdom made 1 acre (0.4 hectare) of ground permanent United States territory as part of a Kennedy memorial at Runnymede. In 1979, the John F. Kennedy Library opened in Boston.

The assassination controversy.

The Warren Commission, headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren, investigated the assassination. In 1964, the commission reported that Oswald had acted alone. But critics disputed the findings. Many Americans—including those who subscribe to conspiracy theories—believed that Oswald was part of a group that had planned to murder Kennedy. Amateur detectives theorized that such groups as organized crime, the Soviets, or even the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had played a role in the assassination. But none of the theories was ever proved.

During the 1970’s, a special committee of the United States House of Representatives reexamined the evidence surrounding the assassination. The committee accepted the testimony of acoustical (sound) experts who claimed that shots were fired from two locations along the motorcade at almost the same time. In 1978, the committee concluded that Kennedy “was probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy.” But other authorities strongly disputed the committee’s conclusion. In 1982, the National Research Council, a scientific research organization, also disagreed with the House committee’s finding.