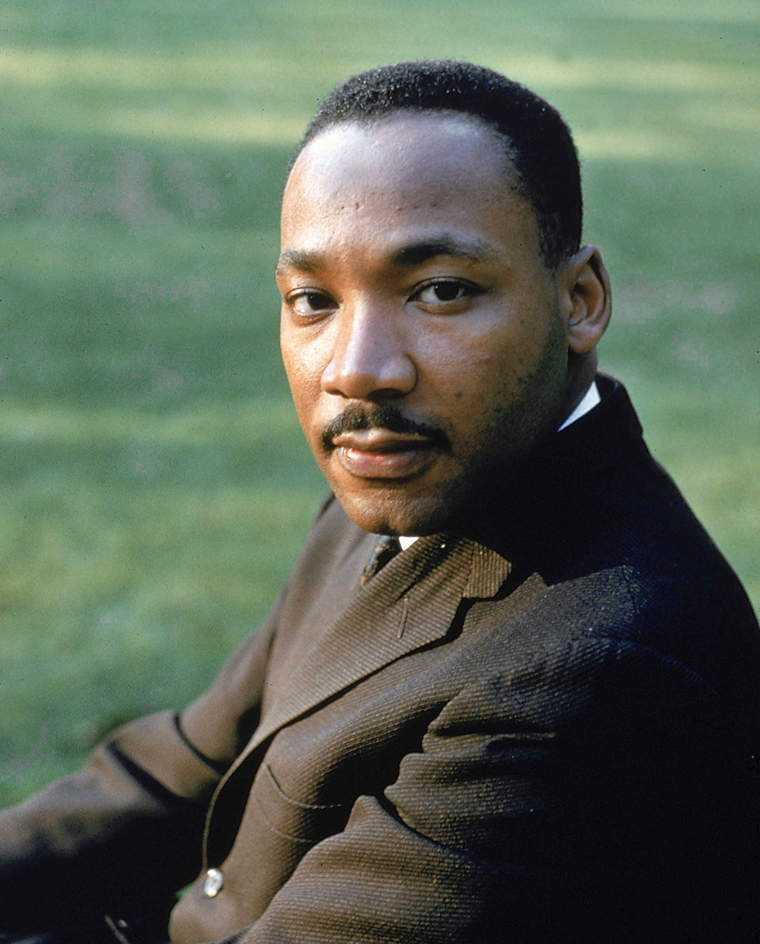

King, Martin Luther, Jr. (1929-1968), an African American Baptist minister, was the main leader of the civil rights movement in the United States during the 1950’s and 1960’s. He had a magnificent speaking ability, which enabled him to effectively express the demands of African Americans for social justice. King’s eloquent pleas won the support of millions of people—both Black and white—and made him internationally famous. He won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize for leading nonviolent civil rights demonstrations.

In spite of King’s stress on nonviolence, he often became the target of violence. White racists bombed his home in Montgomery, Alabama, and threw rocks at him in Chicago. Finally, violence ended King’s life at the age of 39, when an assassin shot and killed him.

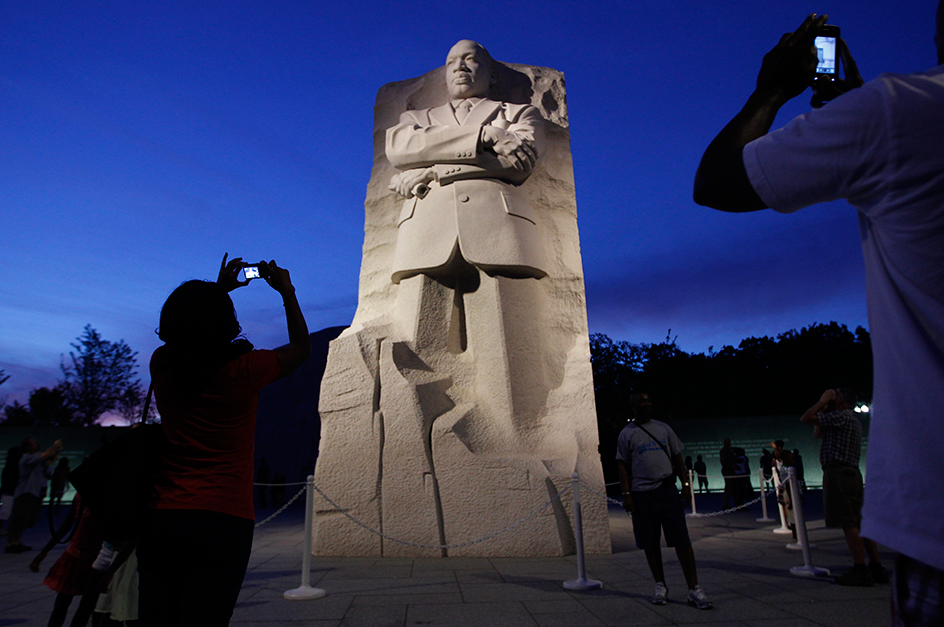

Some historians view King’s death as the end of the civil rights era that began in the mid-1950’s. Under his leadership, the civil rights movement won wide support among white people, and laws that had barred integration in the Southern States were abolished. King became only the second American whose birthday is observed as a national holiday. The first was George Washington, the nation’s first president.

King based his program of nonviolence on Christian teachings. He wrote five books: Stride Toward Freedom (1958), Strength to Love (1963), Why We Can’t Wait (1964), Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967), and The Trumpet of Conscience (1968).

Early life.

King was born on Jan. 15, 1929, in Atlanta. His name at birth was Michael King, Jr., after his father, Michael King. But his father changed their names to Martin Luther King, Sr. and Jr., when the boy was about 5.

Martin was the second oldest child of Alberta Williams King and Michael King. He had an older sister, Christine, and a younger brother, A. D. The young Martin was usually called M. L. His father served as pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. One of Martin’s grandfathers, A. D. Williams, also had been pastor there.

In high school, Martin did so well that he skipped both the 9th and 12th grades. At the age of 15, he entered Morehouse College in Atlanta. King became an admirer of Benjamin E. Mays, Morehouse’s president and a well-known scholar of Black religion. Under Mays’s influence, King decided to become a minister.

King was ordained just before he graduated from Morehouse in 1948. He entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, to earn a divinity degree. King then went to graduate school at Boston University, where he got a Ph.D. degree in theology in 1955. In Boston, he met Coretta Scott of Marion, Alabama, a music student. They were married in 1953. The Kings had four children—Yolanda, Dexter, Martin, and Bernice. In 1954, King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama.

The early civil rights movement.

King’s civil rights activities began with a protest of Montgomery’s segregated bus system in 1955. That year, a Black passenger named Rosa Parks was arrested for disobeying a city law requiring that Black people give up their seats on buses when white people wanted to sit in their seats or in the same row. Black leaders in Montgomery urged Black people to boycott (refuse to use) the city’s buses. The leaders formed an organization to run the boycott and asked King to serve as president. In his first speech as leader of the boycott, King told his Black colleagues: “First and foremost, we are American citizens. … We are not here advocating violence. … The only weapon that we have … is the weapon of protest. … The great glory of American democracy is the right to protest for right.” King’s method of nonviolent protest was inspired by the Indian leader Mohandas K. Gandhi. Gandhi developed a nonviolent method of direct social action that helped India win its independence from the United Kingdom in the 1940’s.

Terrorists bombed King’s home, but King continued to insist on nonviolent protests. Thousands of Black people boycotted the buses for over a year. In 1956, the Supreme Court of the United States ordered Montgomery to provide equal, integrated seating on public buses. The boycott’s success won King national fame and identified him as a symbol of Black Southerners’ new efforts to fight racial injustice. In 1957, King was awarded the Spingarn Medal for his civil rights achievements. The medal is awarded to outstanding African Americans by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

That year, with other Black ministers, King founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to expand the nonviolent struggle against racism and discrimination. At the time, widespread segregation existed throughout the South in public schools, and in transportation, recreation, and such public facilities as hotels and restaurants. Many states also used various methods to deprive Black people of their voting rights. In 1960, King moved from Montgomery to Atlanta to devote more effort to SCLC’s work. He became co-pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church with his father.

The growing movement.

In 1960, Black college students across the South began sitting at lunch counters and entering other facilities that refused to serve Black people. Civil rights protests expanded further, including major demonstrations in Albany, Georgia. Also in the early 1960’s, King became increasingly unhappy that President John F. Kennedy was doing little to advance civil rights. Early in 1963, King and his SCLC associates launched massive demonstrations to protest racial discrimination in Birmingham, Alabama. Birmingham was one of the South’s most segregated cities. Police used dogs and fire hoses to drive back peaceful protesters, including children. Heavy news coverage of the violence produced a national outcry against segregation. Soon afterward, Kennedy proposed a wide-ranging civil rights bill to Congress.

Loading the player...Excerpt from the speech “I Have a Dream,” by Martin Luther King, Jr.

King and other civil rights leaders then organized a massive march in Washington, D.C. The event was called the March on Washington. It was intended to highlight African American unemployment and to urge Congress to pass Kennedy’s bill. On Aug. 28, 1963, about 250,000 Americans, including many white people, gathered at the Lincoln Memorial in the capital. The high point of the rally was King’s stirring “I Have a Dream” speech. The speech eloquently defined the moral basis of the civil rights movement.

Loading the player...Martin Luther King, Jr., receives the Nobel Peace Prize

The movement won a major victory in 1964, when Congress passed the civil rights bill that Kennedy and his successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson, had recommended. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited racial discrimination in public places and called for equal opportunity in employment and education. King later received the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize.

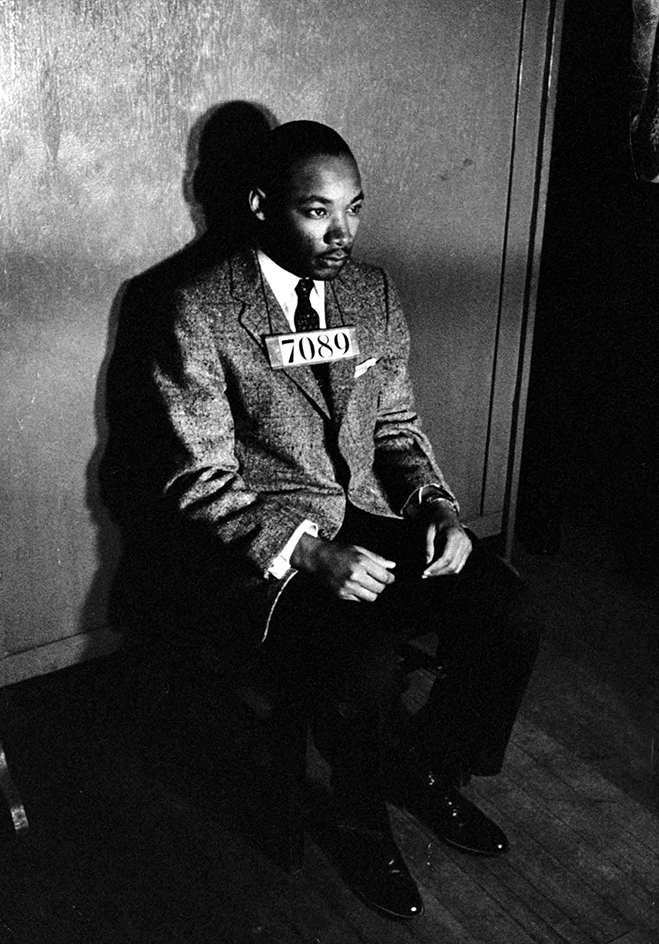

In 1965, King helped organize protests in Selma, Alabama. The demonstrators protested against the efforts of white officials there to deny most Black citizens the chance to register and vote. Several hundred protesters attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital. However, police officers used tear gas and clubs to break up the group. The bloody attack, broadcast nationwide on television news shows, shocked the public. King immediately announced another attempt to march from Selma to Montgomery. Johnson went before Congress to request a bill that would eliminate all barriers to Black Southerners’ right to vote. Within a few months, Congress approved the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Chicago campaign.

By 1965, King had come to believe that civil rights leaders should pay more attention to the economic problems of Black people. In 1966, he helped begin a major civil rights campaign in Chicago, his first big effort outside the South. Leaders of the campaign tried to organize Black inner-city residents who suffered from unemployment, bad housing, and poor schools. The leaders also protested against real estate practices that kept Black people from living in many neighborhoods and suburbs. King believed such practices played a major role in trapping poor Black people in urban ghettos.

King and the local leaders also organized marches through white neighborhoods. Angry white people in these segregated communities threw bottles and rocks at the demonstrators. Soon afterward, Chicago officials promised to encourage fair housing practices in the city if King would stop the protests. King accepted the offer, and the Chicago campaign ended.

Later years.

Continued violence against civil rights workers in the South frustrated many Black people, including members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In 1966, SNCC leaders urged a more aggressive response to the violence and began to use the slogan “Black Power.” That phrase troubled King and many white supporters of racial equality. Many people thought the religious, nonviolent emphasis of the civil rights movement was changing. King repeated his commitment to nonviolence, but disputes among civil rights groups over “Black Power” suggested that King no longer spoke for the whole movement.

In 1967, King became more critical of American society than ever before. He believed poverty was as great an evil as racism. He said that true social justice would require a redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor. Thus, King began to plan a Poor People’s Campaign that would unite poor people of all races in a struggle for economic opportunity. The campaign would demand a federal guaranteed annual income for poor people and other major antipoverty laws.

Also in 1967, King attacked U.S. support of South Vietnam in the Vietnam War (1957-1975). He regarded the South Vietnamese government as corrupt and undemocratic. Many supporters of the war denounced King’s criticisms, but the growing antiwar movement welcomed his comments.

King’s death.

While organizing the Poor People’s Campaign, King went to Memphis to support a strike of Black garbage workers. On April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, King was shot and killed. James Earl Ray, a white drifter and escaped convict, pleaded guilty to the crime in March 1969 and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. Ray later tried to withdraw his plea, but his conviction was upheld. Ray died in prison in 1998.

People throughout the world mourned King’s death. King was buried in South View Cemetery in Atlanta. His body was later moved near Ebenezer Baptist Church. On King’s tombstone are the words: “Free at last, free at last, thank God Almighty, I’m free at last.”

King’s assassination produced immediate shock, grief, and anger. Black people rioted in more than 100 cities. A few months later, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which prohibited racial discrimination in the sale and rental of most housing in the nation.

Years after King’s death, some people still doubted that Ray had acted alone. In 1978, a special committee of the U.S. House of Representatives reported the “likelihood” that Ray was aided by others. In 2000, however, the U.S. Justice Department announced that an 18-month investigation turned up no evidence of a conspiracy.

In 1974, King’s mother was shot and killed while playing the organ at Ebenezer Baptist Church. The gunman, Marcus Wayne Chenault, opposed Black Christian ministers. He received the death penalty but in 1995 was resentenced to life in prison without parole. King’s son Martin Luther King III served as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference from 1997 to 2004. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, died in 2006.