Laurier, << lawr YAY or LAW ree ay, >> Sir Wilfrid (1841-1919), was the first French Canadian to become prime minister of Canada. He held the office from 1896 to 1911. Laurier served in Parliament for 45 years and was leader of the Liberal Party for 32 years. Throughout his long public career, Laurier worked to unite French-speaking and English-speaking Canadians for the good of Canada. He also laid the foundation for Canadian independence by opposing strong ties with the British Empire. During Laurier’s term as prime minister, Canada enjoyed great prosperity. The settlement of western Canada led to the establishment in 1905 of two new western Prairie Provinces—Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The “Old Chief,” as many called Laurier, looked like a model of an aristocrat. He wore a black frock coat with a vest. His coat lapels were lined with a white frill. His collar rose high and straight, and his tie was so wide that it hid his shirt.

Laurier spoke English and French fluently. He became one of the outstanding orators in Canadian history. He used few gestures as he spoke, but the rich tones of his voice often held audiences spellbound.

Early life

Boyhood and education.

Wilfrid Laurier was born on Nov. 20, 1841, in Quebec in the village of Saint-Lin, near L’Epiphanie. His ancestors had come to Canada from Normandy, France. One of them was a soldier under Paul de Chomedey, Sieur de Maisonneuve, who founded Montreal in 1642.

Wilfrid’s mother, Marie Marcelle Martineau Laurier, died when he was 6 years old. His father, Carolus Laurier, later married Adelaine Ethier. Wilfrid had three half brothers and a half sister.

Carolus Laurier was a farmer and surveyor. A man of strong liberal beliefs, he did not want Wilfrid to grow up knowing only the French culture. When Wilfrid was about 11, his father sent him to live for two years with a Scots-Canadian family in a neighboring village. There the boy learned the English language and became familiar with English ways of life.

Laurier attended L’Assomption College, a FrenchCanadian school in L’Assomption, Quebec. He liked public speaking and helped form a debating society there.

In 1861, Laurier began to study law at McGill University in Montreal. His father had little money at this time, and Wilfrid took a part-time job with the Montreal law firm of Laflamme and Laflamme. Rodolphe Laflamme, the head of the firm, was an active Liberal. Laurier received his law degree in 1864.

Young lawyer.

Laurier practiced law in Montreal for two years after his graduation. In 1866, he developed a serious lung ailment. At the suggestion of a friend, Laurier moved to Arthabaska, a new settlement in eastern Quebec. He hoped the country air would restore his health. In Arthabaska, he became a popular and successful lawyer. He also edited the newspaper Le Defricheur for about six months. Laurier wrote editorials that Roman Catholic leaders considered too radical. The newspaper went out of business, chiefly because of lack of funds.

Laurier married Zoe Lafontaine (1841-1921) of Montreal on May 13, 1868. The couple lived in Arthabaska until Laurier became prime minister. They often returned there for rest during the busy years that followed. The Lauriers had no children.

Early public career

In 1871, at the age of 29, Laurier was elected to the Quebec legislature as a Liberal. Three years later, in 1874, Laurier was elected to the federal parliament in Ottawa.

The poet Louis-Honore Frechette described reaction to Laurier’s first speech in the House of Commons: “… Who could be this young politician … who thus, in a maiden speech handled the deepest public questions with such boldness and authority? … On the following day, the name of Laurier was on every lip. … It seemed as if every one realized that a future chieftain had just proclaimed himself…”

In 1877, Laurier accepted the invitation of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie to join his cabinet as minister of inland revenue. He held the office for less than a year because the Liberals were defeated in the 1878 election. For the next 18 years, until he became prime minister, Laurier sat on the opposition side of the House of Commons.

During the late 1800’s, the Liberals in Quebec met strong opposition from the Roman Catholic Church. In 1877, Laurier made a speech on liberalism that became a classic in Canadian political history. In this speech, he distinguished between liberalism in politics and liberalism in religion. Laurier declared that French-Canadian Catholics had the right to form their own political opinions without interference from the church. But he warned against the possible creation of a French-Canadian Catholic political party. Such a party, Laurier said, would inevitably be met by an English-Canadian Protestant party that would oppose the French Canadians. And, he pointed out, most Canadians were English-speaking Protestants.

In 1880, Edward Blake succeeded Alexander Mackenzie as leader of the Liberal Party. Laurier became Blake’s aide and leader of the party’s Quebec wing.

The execution of Louis Riel

in 1885 brought Laurier back into the spotlight. Riel had led a rebellion of metis (people of mixed white and Indian ancestry) in Saskatchewan against the federal government. The metis revolted in fear of being thrown off their lands. Riel was captured and sentenced to death. Many French Canadians considered Riel a hero, and demanded that he be pardoned. But many English Canadians demanded his death for treason. Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald let the sentence stand, and Riel was hanged. See Riel, Louis .

French Canadians in Montreal staged a demonstration against Riel’s execution. Laurier joined in the protest. He declared that if he had lived along the Saskatchewan River, where the revolt started, he would have shouldered his musket along with the metis. Blake joined Laurier in protesting Riel’s execution. But most Liberals outside Quebec refused to follow them. The Conservatives won the 1887 election.

The Liberal Party had now lost three successive elections—in 1878, 1882, and 1887. In despair, Blake resigned as Liberal Party leader. He advised the party to elect Laurier as his successor. On June 7, 1887, Laurier became leader of the Liberal Party. Most English-speaking Liberals, as well as Laurier himself, felt that because he was a French Canadian he could never win the support of English-speaking Canadians.

Laurier wanted to distract attention from the bitter English-French quarrel over Riel. Partly in an effort to do so, he proposed an unrestricted reciprocal trade agreement with the United States (see Reciprocal trade agreement ). Prime Minister Macdonald opposed such a pact. He declared that completely free trade would lead to eventual political union with the United States. In the election of 1891, Macdonald and the Conservatives defeated Laurier and the Liberals on the issue of trade with the United States.

Macdonald died in June 1891. During the next five years, the Conservative Party slowly lost popularity under the leadership of four Conservative prime ministers—Sir John J. C. Abbott (1891-1892), Sir John S. D. Thompson (1892-1894), Sir Mackenzie Bowell (1894-1896), and Sir Charles Tupper (1896).

The Manitoba school issue

brought Laurier and the Liberals to power. In 1890, the Manitoba legislature had abolished tax support for Roman Catholic schools in the province. It felt that one school system for all children would be more efficient than separate public and Roman Catholic schools. Catholics in Manitoba charged that they were being deprived of their constitutional rights. In 1895, the Canadian government ordered Manitoba to restore tax funds to the Catholic schools. Manitoba refused. In 1896, the Conservative government introduced a bill providing for separate schools in Manitoba. The issue was hotly debated in the election of that year. Laurier declared that a compromise could be reached by “sunny ways” rather than by force. Although many Roman Catholic leaders opposed Laurier, French Canadians supported him. The Liberals won the election.

Prime minister (1896-1911)

At the age of 54, Wilfrid Laurier took office as prime minister of Canada on July 11, 1896. He succeeded Sir Charles Tupper, a Conservative. Laurier soon worked out a compromise solution in the Manitoba school problem. The province agreed to permit religious teaching and the use of French during certain periods of the school day. The amount of such instruction was based on the number of pupils who desired it.

When Laurier came to power, a long period of falling prices was ending. Europe had grown prosperous and had become a booming market for Canadian wheat and other food products. Laurier acted to take advantage of the favorable economic situation. During his administration, the government helped about 2 million immigrants enter Canada. Most of the newcomers settled on the western prairies. The government also helped build the Canadian Northern and the Grand Trunk Pacific railways to carry out the wheat that the settlers grew. The country enjoyed its greatest prosperity since 1867. The Liberals won reelection in 1900, 1904, and 1908. Queen Victoria knighted Laurier in 1897.

Prosperity helped soften the conflict between French and English Canadians. But in 1905, when the government established two new provinces—Saskatchewan and Alberta—Laurier allowed each of them to have a separate Roman Catholic school system. Another storm over religion and education arose.

Relations with the United Kingdom

caused further hostility between English and French Canadians. The chief question was what action Canada would take if the United Kingdom should go to war.

In 1897, the British colonial secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, suggested closer economic ties between members of the British Empire. Laurier’s government agreed that year to decrease tariffs on British goods. But Laurier opposed any system that would bind the United Kingdom and the British colonies in one economic unit. Laurier maintained his opposition to the empire as a close-knit unit at the four Imperial Conferences that he attended in 1897, 1902, 1907, and 1911.

In 1899, the United Kingdom went to war against the Boers in South Africa (see Anglo-Boer Wars ). English Canadians demanded that Canada send troops to support the United Kingdom. French Canadians opposed any government aid to the United Kingdom. Laurier spent government funds to equip Canadian volunteers and send them to Africa. French Canadians protested strongly. Even Henri Bourassa, Laurier’s most promising French-Canadian lieutenant, rebelled against the policy. From that point on, French Canadians and English Canadians became more divided on the role of Canada in the British Empire.

By 1910, the United Kingdom faced the threat of war with Germany. Laurier decided to build a Canadian navy to support the United Kingdom if war began. Parliament approved his Naval Service Bill, but many Canadians opposed it. Some French Canadians thought Laurier “too British” because he had supported the United Kingdom. Some English Canadians considered him “too French” because of his opposition to closer ties with the United Kingdom.

Defeat.

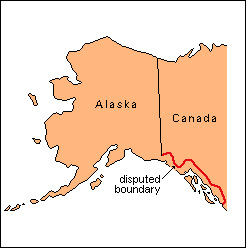

In 1911, the United States offered Canada a limited reciprocal trade treaty. Laurier accepted, and the governments drew up an agreement that seemed to give equal benefits to each. But a number of Canadians still feared domination by the United States. Many resented the settlement in 1903 of the Alaska border dispute between the two countries (see Alaska (The early 1900’s) ).

The Liberals lost the election of September 1911, chiefly because of the public’s opposition to the naval bill and the trade agreement with the United States. In Quebec, Bourassa helped defeat Laurier by forming an alliance with the Conservatives. Robert L. Borden, a Conservative, became prime minister.

Later years

The conscription crisis.

For the rest of his life, Sir Wilfrid Laurier continued to serve as leader of the Liberal Party. When World War I began in 1914, he supported the Conservative government in joining the war to aid the United Kingdom.

As the war dragged on, it became clear that far fewer French Canadians than English Canadians were enlisting for military service. By 1917, the Canadian forces fighting in Europe needed replacements. Until then, all Canadian servicemen had enlisted voluntarily. Prime Minister Borden decided that conscription (drafting of men for military service) had become necessary. Borden wanted both parties to approve conscription so that unity could be kept among all Canadians. To carry out the policy, Borden asked Laurier to join a Union Government made up of Liberals and Conservatives. Laurier refused. He felt he would lose control of the Liberals in Quebec if he joined the proposed government. Bourassa and his followers also firmly opposed conscription. They felt they had no direct responsibility in the war.

Most of Laurier’s English-Canadian followers broke away from him and helped Borden form the Union Government. They felt that Laurier was too concerned with keeping his hold on Quebec and that he did not consider the national interests of Canada as a whole. But Laurier felt it would be dangerous if Bourassa’s radical nationalism replaced his moderate leadership.

In the election of December 1917, English Canadians voted overwhelmingly for the Union Government. Prime Minister Borden stayed in power. But most French Canadians voted against the Union Government and conscription.

The split between English and French Canadians saddened Laurier. Ever since entering Parliament more than 40 years before, he had worked to unite the two groups. But later events proved that his efforts had not been in vain. After Laurier died in 1919, W. L. Mackenzie King reunited French- and English-Canadian Liberals.

Death.

Sir Wilfrid Laurier died on Feb. 17, 1919, at the age of 77. He was buried in Ottawa. Lady Laurier died in 1921. In her will, she left Laurier House, their home in Ottawa, to Mackenzie King. After King died in 1951, the Canadian government made Laurier House a museum. Laurier’s birthplace at St. Lin is a national historic site.