Learning is an important field of study in psychology. Psychologists define learning as the process by which changes in behavior result from experience or practice. By behavior, psychologists mean any response that an organism makes to its environment. Thus, behavior includes actions, emotions, thoughts, and the responses of muscles and glands. Learning can produce changes in any of these forms of behavior.

Not all changes in behavior are the result of learning. Some changes result from maturation (physical growth). Others, including those caused by illness or fatigue, are only temporary and cannot be called learning.

How we learn

We can see learning taking place all the time, but there is no simple explanation of the process. Psychologists have examined four kinds of learning in detail: (1) classical conditioning or respondent learning, (2) instrumental conditioning or operant learning, (3) multiple-response learning, and (4) insight learning.

Classical conditioning

is based on stimulus-response relationships. A stimulus is an object or a situation that excites one of our sense organs. A light is a stimulus because it excites the retina of the eye, allowing us to see. Often a stimulus makes a person respond in a certain way, as when a flash of light makes us blink. Psychologists say that in this instance the stimulus elicits (draws forth) the response.

In classical conditioning, learning occurs when a new stimulus begins to elicit behavior similar to that originally produced by an old stimulus. For example, suppose a person tastes some lemon juice, which makes the person salivate. While the person is tasting it, a tone is sounded. Suppose these two stimuli—the lemon juice and the tone—occur together many times. Eventually, the tone by itself will make the person salivate. Classical conditioning has occurred because the new stimulus (the tone) has begun to elicit the response of salivation in much the same way as the lemon juice elicited it.

Any condition that makes learning occur is said to reinforce the learning. When a person learns to salivate to a tone, the reinforcement is the lemon juice that the tone is paired with. Without the lemon juice, the person would not learn to salivate to the tone.

The classical conditioning process is particularly important in understanding how we learn emotional behavior. When we develop a new fear, for example, we learn to fear a stimulus that has been combined with some other frightening stimulus.

Studies of classical conditioning are based on experiments performed in the early 1900’s by the Russian physiologist Ivan P. Pavlov. He trained dogs to salivate to such signals as lights, tones, or buzzers by presenting these signals when he gave food to the dog (see Reflex action ). Pavlov called the learned response a conditioned response because it depended on the conditions of the stimulus. To emphasize the fact that a stimulus produces a response in this kind of learning, classical conditioning is often called respondent learning.

Instrumental conditioning.

Often a person learns to perform a response as a result of what happens after the response is made. For example, a child may learn to beg for candy. There is no one stimulus that elicits the response of begging. The child begs because such behavior occasionally results in receiving candy. Every time the child receives candy, the tendency to beg becomes greater. Candy, therefore, is the reinforcer. Instrumental conditioning is also called operant conditioning because the learned response operates on the environment to produce some effect.

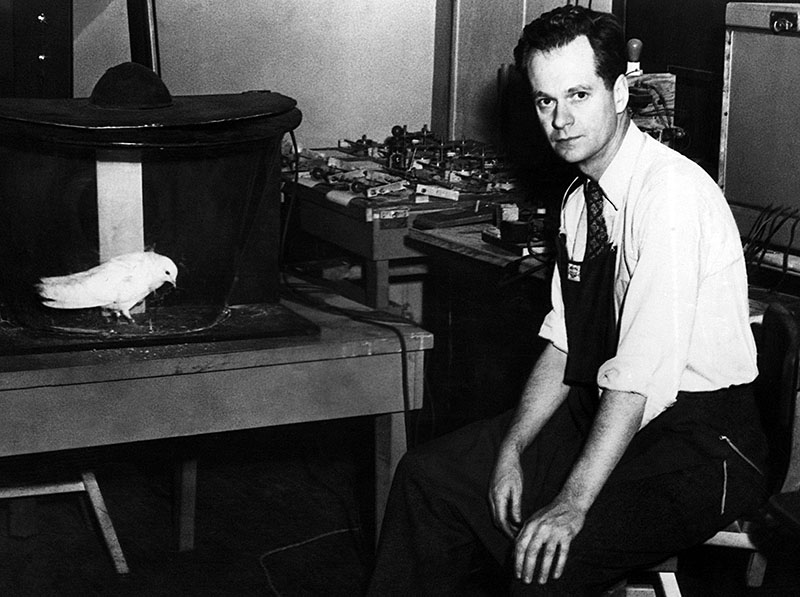

The American psychologist B. F. Skinner performed important experiments with instrumental conditioning in the 1930’s. He trained rats to press levers to get food. In one experiment, a hungry rat was placed in a special box containing a lever attached to some concealed food. At first, the rat ran around restlessly. Eventually, it happened to press the lever, and the food dropped into the box. The food reinforced the response of pressing the lever. After repeating the process many times, the rat learned to press the lever for food.

Skinner’s experiments were based on those performed earlier in the 1900’s by the American psychologist E. L. Thorndike. In Thorndike’s experiments, an animal inside a puzzle box had to pull a string, press a pedal, or make some other response that would open the box and expose some food. Thorndike noted that the animal learned slowly and gradually. He called this type of learning trial-and-error behavior.

Multiple-response learning.

When we learn skills, we first learn a sequence of simple movement-patterns. We combine these movement-patterns to form a more complicated behavior pattern. In most cases, various stimuli guide the process. For example, operating a typewriter requires putting together many skilled finger movements. These movements are guided by the letters or words that we want to type. At first, a person has to type letter by letter. With practice, the person learns to type word by word or phrase by phrase. In verbal learning, such as memorizing a poem or learning a new language, we learn sequences of words. We then combine these sequences of responses into a complex organization. Learning that involves many responses requires much practice to smooth out the rough spots.

To examine this kind of learning, psychologists have observed animals learning to run through a maze. Starting at the beginning, the animal wanders through the maze until it finds food at the end. The animal periodically comes to a choice-point, where it must turn right or left. Only one choice is correct. Eventually the animal learns the correct sequence of turns. Psychologists have found that the two ends of the maze are learned more easily than the parts near the middle. In the same way, when we learn a list of things, we usually find the beginning and end easier than the middle.

Insight learning.

The term insight refers to solving a problem through understanding the relationships of various parts of the problem. Insight often occurs suddenly, such as when a person looks at a certain problem for some time and then suddenly grasps its solution.

The psychologist Wolfgang Kohler performed important insight experiments in the early 1900’s. He showed that chimpanzees sometimes use insight instead of trial-and-error responses to solve problems. When a banana was placed high out of reach, the animals discovered that they could stack boxes on top of each other to reach it. They also discovered how to put two sticks together to reach an object that was too far away to reach with one stick. The chimpanzees appeared both to see and to use the relationships involved in reaching their goals.

Theories of learning

are based on facts obtained from experiments such as those on classical and instrumental conditioning. Psychologists differ in their interpretation of these facts. As a result, there are a number of learning theories. These theories can be divided into three groups.

One group of psychologists emphasizes stimulus-response relationships and has performed experiments with classical and instrumental conditioning. They say all learning is the forming of habits. When we learn, we connect a stimulus and a response that did not exist before, thus forming a habit (see Habit ). Habits can range from the simplest ones to complex ones that are involved in learning skills. These psychologists believe that when we meet a new problem, we use appropriate responses learned from past experience to solve it. If this procedure does not lead to the solution, we use a trial-and-error approach. We use one response after another until we solve the problem. The stimulus-response approach has been used to explain and modify bad habits. For example, when a person is irrationally afraid of dogs, methods called behavior modification can be used to replace the fear response to a dog with a more relaxed response.

A second group of psychologists stresses cognition (the act of knowing) above the importance of habit. These experts feel that experiments with classical and instrumental conditioning are too limited to explain such complex learning as understanding concepts and ideas. This approach emphasizes the importance of the learner’s discovering and perceiving new relationships and achieving insight and understanding.

A third group of psychologists has developed humanistic theories. According to these theories, much human learning results from the need to express creativity. Almost any activity, including athletics, business dealings, and homemaking, can serve as a creative outlet. The psychologists in this group believe that each person must become involved in challenging activities—and must do reasonably well at them—to have a satisfying life. The individual gains a sense of control, growth, and knowledge from such activities. For learning to occur, people must feel free to make their own decisions. They also must feel worthy, relatively free from anxiety, self-respecting, and respected by others. Under these conditions, their own inner drives will lead them to learn. Some kinds of group therapy try to provide an accepting, supporting environment. Such an environment is intended to increase people’s awareness of their own thoughts and of the world around them.

Learning involves changes in the nervous system. Scientists are trying to discover the processes that take place in the brain to produce learning. Such research may lead to a physiological theory of learning.

Efficient learning

Readiness to learn.

Learning occurs more efficiently if a person is ready to learn. This readiness results from a combination of growth and experience. Children cannot learn to read until their eyes and nervous systems are mature enough. They also must have a sufficient background of spoken words and prereading experience with letters and pictures.

Motivation.

Psychologists and educators also recognize that learning is best when the learner is motivated to learn (see Motivation ). External rewards are often used to increase motivation to learn. Motivation aroused by external rewards is called extrinsic motivation. In other cases, people are motivated simply by the satisfaction of learning. Motivation that results from such satisfaction is called intrinsic motivation. This type of motivation can be even more powerful than extrinsic motivation. Punishment, particularly the threat of punishment, is also used to control learning. Experiments have shown that intrinsic and extrinsic rewards serve as more effective aids to learning than punishment does. This is due largely to two factors: (1) learners can recognize the direct effects of reward more easily than they can the effects of punishment; and (2) the by-products of reward are more favorable. For example, reward leads to liking the rewarded task, but punishment leads to dislike of the punished deed.

Psychologists also look at the motivation of learning from the point of view of the learner. They tend to talk about success and failure, rather than reward and punishment. Success consists of reaching a goal that learners set for themselves. Failure consists of not reaching the goal. An ideal learning situation is one in which learners set progressively more difficult goals for themselves, and keep at the task until they succeed.

Skill learning and verbal learning.

Through research, psychologists have discovered some general rules designed to help a person learn.

The following rules apply particularly to learning skills. (1) Within a given amount of practice time, you can usually learn a task more easily if you work in short practice sessions spaced widely apart, instead of longer sessions held closer together. (2) You can learn many tasks best by imitating experts. (3) You should perform a new activity yourself, rather than merely watch or listen to someone. (4) You learn better if you know immediately how good your performance was. (5) You should practice difficult parts of a task separately and then try to incorporate them into the task as a whole.

Two additional rules apply mainly to verbal learning. (1) The more meaningful the task, the more easily it is learned. You will find a task easier to learn if you can relate it to other things you have learned. (2) A part of a task is learned faster when it is distinctive. When studying a book, for example, underlining a difficult passage in red makes the passage distinctive and easier to learn.

Transfer of training.

Psychologists and educators recognize that new learning can profit from old learning because learning one thing helps in learning something else. This process is called transfer of training.

Transfer of training can be either positive or negative. Suppose a person learns two tasks. After learning Task 1, the person might find Task 2 easier or harder. If Task 2 is easier, then the old learning has been a help and positive transfer of training has occurred. If Task 2 is harder, the old learning is a hindrance and negative transfer has occurred.

Whether transfer is positive or negative depends on the relationship between the two tasks. Positive transfer occurs when the two tasks have similar stimuli and both stimuli elicit the same response. For example, if we know the German word gross, it is easier to learn the French word gros because both words mean large. In this case, similar stimuli (gross and gros) elicit the same response (large).

Negative transfer occurs when the two tasks have similar stimuli, which elicit different responses. After you learn the German word Gras (grass), it is harder to learn the French word gras (fat). The words are similar, but they have different meanings. In this case, similar stimuli (Gras and gras) elicit different responses.

Psychologists believe new learning can profit from old learning because of three factors: (1) positive transfer of training, (2) general principles that we learn in one task and apply to another task, and (3) good study habits that we learn in one task which help us learn another task.