Louisiana Purchase was the most important event of President Thomas Jefferson’s first administration. In this transaction, the United States bought 827,987 square miles (2,144,476 square kilometers) of land from France for about $15 million. This vast area lay between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border. The purchase of this land greatly increased the economic resources of the United States, and cemented the union of the Middle West and the East. Eventually all or parts of 15 states were formed out of the region.

Reasons for the purchase.

When Jefferson became president in March 1801, the Mississippi River formed the western boundary of the United States. The southern boundary extended to the 31st parallel north latitude. The Floridas (with West Florida extending to the Mississippi and including New Orleans) lay to the south, and the Louisiana Territory to the west. Spain owned both these territories.

Farmers who lived west of the Appalachian Mountains shipped all their surplus produce by boat down rivers that flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, especially the Mississippi. In a treaty of 1795, Spain agreed to give Americans the “right of deposit” at New Orleans. This right allowed Americans to store in New Orleans, duty-free, goods shipped for export. Arks and flatboats transported a great variety of products, including flour, tobacco, pork, bacon, lard, feathers, cider, butter, cheese, hemp, potatoes, apples, salt, whiskey, beeswax, and bear and deer skins.

Spain suspended the right of deposit in 1798, arousing a strong reaction among Westerners. In 1800, Spain transferred Louisiana to France in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso. Emperor Napoleon I of France assigned an army and a general for the occupation of Louisiana, but Spanish authorities continued to govern. In June 1801, Spanish governor Don Juan Manuel de Salcedo replaced Governor Casa Calvo, and the right of deposit for United States goods was reinstated for a short time.

Trouble begins.

In the same month that Jefferson became president, the United States minister to the United Kingdom, Rufus King, heard that Spain planned to give part of its American colonies to France. Jefferson feared that an ambitious nation such as France might interfere with the trade of the western territories. He believed that Spain would cede the Floridas to France, and quickly directed his diplomats to prevent this transfer. Secretary of State James Madison warned the French charge d’affaires, Louis Pichon, that the United States expected to have an outlet to the sea. Robert Livingston, who was the newly appointed minister to France, sailed for that country in September 1801. He had received instructions to inform the French government that the United States was not willing to see the American colonies of Spain transferred to any country except the United States.

In November 1801, King sent Madison a copy of the treaty in which Spain ceded Louisiana to France. But Jefferson still did not know just how much territory this included. He instructed Livingston to prevent the cession if possible. If it had already taken place, Livingston was to persuade France to transfer the Floridas, especially West Florida, to the United States. New Orleans lay on the east side of the river, so it would become a possession of the United States. Napoleon spurned Livingston’s proposals.

A French colonial official sent by Napoleon to receive the transfer of Louisiana from Spain to France arrived in New Orleans in March 1802. But the French army intended for Louisiana was diverted to the colony of Santo Domingo in the French West Indies to suppress a slave rebellion. Though the rebellion was stopped, yellow fever and continuing rebel activities reduced French forces, and the transfer of Louisiana to France was delayed.

Jefferson arranged for his friend Pierre du Pont de Nemours to carry dispatches to Livingston and to help him influence the French government against acquiring the American Colonies. Du Pont’s instructions read as follows: “… you may be able to impress on the government of France the inevitable consequences of their taking possession of Louisiana … This measure will cost, and perhaps not very long hence, a war which will annihilate her on the ocean …” Du Pont was to warn France that if it annexed Louisiana, the United States would form an alliance with the United Kingdom against France. Du Pont felt that this ultimatum might make Napoleon even more determined to acquire the desired territory. Being a businessman, he suggested that the United States offer to buy the Floridas, paying as much as $6 million. This seems to be the first suggestion of buying the territory.

New Orleans closed to Americans.

Meanwhile, Jefferson’s worst fears seemed to be confirmed when, on Oct. 18, 1802, Governor Salcedo again suspended the right of deposit. He was following orders received from Spain, probably dictated by Napoleon, but the action was made to appear as his own decision. The governor of the Mississippi Territory warned Madison: “The late act of the Spanish Government at New Orleans has excited considerable agitation in Natchez and its vicinity:–It has inflicted a severe wound upon the Agricultural and Commercial interests of this Territory, and must prove no less injurious to all the Western Country.” Madison protested to the Spanish government and also warned Napoleon through Pichon that Americans were people of action and were aroused by a war fever.

Napoleon refused to abandon his hopes of building an empire in America. The news of a military defeat in Santo Domingo only caused him to send another 15,000 French troops there. Livingston was discouraged. Jefferson decided to send James Monroe to France to support Livingston in his negotiations with the French government. Congress voted $2 million which the two envoys could use in trying to purchase the east bank of the Mississippi. Jefferson privately advised them to offer as much as $9,375,000 for the Floridas and New Orleans. If France rejected their offer, they were to try to obtain at least the right of deposit at New Orleans.

Napoleon’s decision.

Napoleon knew that war with the United Kingdom would soon break out again. Pichon warned him that the Americans might seize Louisiana as soon as France became engaged in a European war, and that the British Navy might seize the territory. Napoleon also feared the possibility of an Anglo-American alliance. Pichon had warned that the United States was considering sending 50,000 troops to take New Orleans by force. American newspapers describing the war ferment seemed to substantiate this warning.

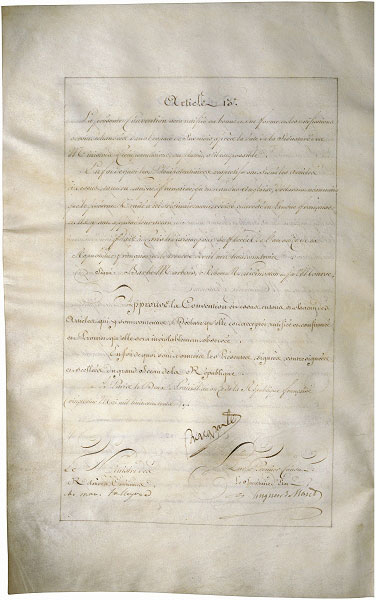

On April 10, 1803, Napoleon notified his finance minister, Francois de Barbe-Marbois, that he was considering ceding all the Louisiana Territory to the United States. Monroe arrived in Paris just after Talleyrand, the French foreign minister, had offered Livingston the whole of Louisiana. Jefferson had instructed the two envoys to purchase only the Floridas, but they felt confident that the United States would accept this larger offer. They agreed to Marbois’ price of 60 million francs plus the assumption of American claims against France (a total of about $15 million). The treaty, dated April 30, was signed May 2. It reached Washington on July 14, 1803.

Ratifying the treaty.

The Constitution did not authorize the acquisition of land, but it did provide for the making of treaties, so that Jefferson felt the acquisition of new territory was constitutional. He admitted that he had “stretched the constitution until it cracked.” But he thought of himself as a guardian who made an investment of funds entrusted to his care. In a message to Congress on Oct. 17, 1803, Jefferson said: “Whilst the property and sovereignty of the Mississippi and its waters secure an independent outlet for the produce of the Western States and an uncontrolled navigation through their whole course, … the fertility of the country, its climate and extent, promise in due season important aids to our Treasury, an ample provision for our posterity, and a wide spread for the blessings of freedom and equal laws.” The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty on October 20. Laws were passed to provide for borrowing the money from English and Dutch banks. These debts were payable in 15 years. The United States officially took possession of the territory on Dec. 20, 1803. See Louisiana (History) .

Boundary disputes

arose over the Louisiana Territory, because the treaty did not state specific boundaries. The United States and the United Kingdom agreed in 1818 to establish the northern boundary at the 49th parallel. In the south, the United States claimed West Florida and part of Texas. Jefferson pointed out that as early as 1696 France had possession of the Gulf Coast from Mobile westward, and that in 1755 maps published by the French government showed the Perdido River as the eastern boundary of France’s possessions. This, Jefferson claimed, was part of the land that Spain gave back to France in 1800, and therefore part of the purchase. In the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819 with Spain, the United States acquired Florida, and surrendered its claim to Texas. Spain in return gave up its claim to West Florida.