Lymphatic, << lihm FAT ihk, >> system is a network of small vessels that resemble blood vessels. The lymphatic system returns fluid from body tissues to the bloodstream. This process is necessary because the body continuously filters water, proteins, and other molecules out of tiny blood vessels called capillaries. The fluid that has leaked out, called interstitial fluid, bathes and nourishes body tissues.

If there were no way for excess interstitial fluid to return to the blood, tissues would become swollen. Some of the extra fluid seeps into capillaries that have low fluid pressure. The rest returns by way of the lymphatic system and is called lymph. Some scientists consider the lymphatic system to be part of the circulatory system because lymph comes from blood and returns to blood.

The lymphatic system also is one of the body’s defenses against infection. Harmful particles and bacteria that have entered the body are filtered out by small masses of tissue that lie along the lymphatic vessels. These bean-shaped masses are called lymph nodes.

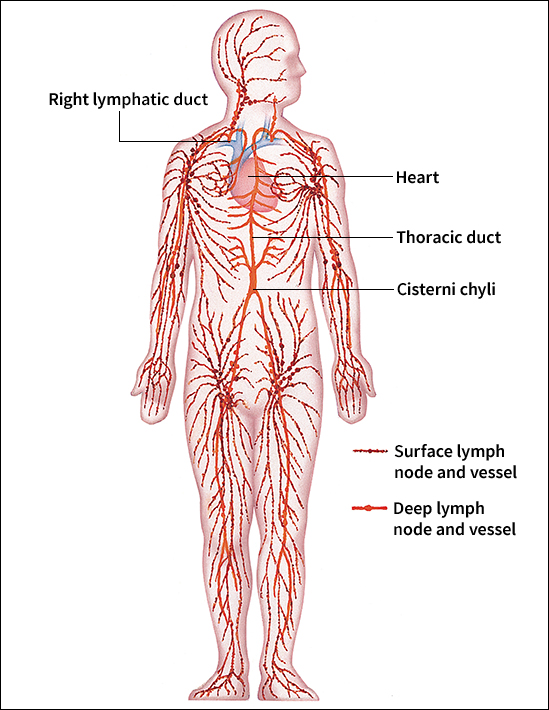

Parts of the lymphatic system

Lymphatic vessels,

like blood vessels, are found throughout the body. Most organs, including the heart, lungs, intestines, liver, and skin have lymphatic vessels. The brain, however, has no lymphatic vessels.

Lymph flows from tiny vessels with many branches into larger vessels. Eventually, lymph from all but the upper right quarter of the body reaches the thoracic duct, the largest lymphatic vessel. The thoracic duct lies along the front of the spine. Lymph flows upward through this duct into a blood vessel near the junction of the neck and the left shoulder. Lymph from the upper right quarter of the body flows into the right lymphatic ducts in the right half of the chest. The lymph then drains from these ducts into the bloodstream near the junction of the neck and right shoulder.

Lymph

is chemically much like plasma, the liquid in which blood cells are suspended. But lymph contains only about half as much protein as plasma, because large protein molecules do not seep through blood vessel walls so easily as do some other substances. Lymph is transparent and straw-colored.

Lymph nodes

may be found at many places along the lymphatic vessels. They look like bumps and have diameters from 1/25 to 1 inch (1 to 25 millimeters). The term node comes from the Latin word nodus, meaning knot, and lymph nodes resemble knots in a “string” of lymphatic vessels. The nodes are bunched together in certain areas, especially in the neck and armpits, above the groin, and near various organs and large blood vessels. Lymph nodes contain large cells called macrophages that absorb harmful matter and dead tissue.

Lymphocytes

are a kind of white blood cell present in the lymph nodes. They defend the body against infection. When abnormal cells or materials from outside the body pass into the lymph nodes, lymphocytes in the nodes produce substances called antibodies. The antibodies either destroy the abnormal or foreign matter or make it harmless. See Immune system .

Large numbers of lymphocytes are found in the lymph nodes and in lymph itself. They outnumber all other kinds of cells in lymph.

Lymphoid tissue

resembles the tissue of the lymph nodes. It is found in some parts of the body that are not generally considered part of the lymphatic system. For example, the adenoids and tonsils, the spleen, and the thymus consist of lymphoid tissue. This tissue produces and contains lymphocytes, and it aids in the body’s defense against infection.

Work of the lymphatic system

Return of interstitial fluid.

Interstitial fluid is produced continuously by seepage from the capillaries. For this reason, some of the fluid must constantly be returned from body tissues to the bloodstream. If the lymphatic vessels are blocked, fluid gathers in nearby tissues and causes swelling called edema.

Lymph only flows in one direction—toward the thoracic duct. Valves along the lymphatic channels prevent the lymph from flowing backward. The larger lymphatic vessels have a thin layer of muscle in their walls. Contraction of these muscles propels lymph through the lymph channels. In this way, lymph can be transported upward, against gravity, toward the thoracic duct. The smallest lymphatic vessels have no muscle of their own. Expansion and compression of these vessels result from movement of surrounding tissue. Thus, lymph flow is caused by breathing, by the pulsebeat in nearby blood vessels, by muscular and intestinal movement, and by skin massage.

Fighting infection.

Lymphocytes and macrophages both play vital roles in fighting infection—lymphocytes by producing antibodies and macrophages by swallowing up foreign particles. During an infection, the lymph nodes that drain an infected area may swell and become painful. The swelling indicates that the lymphocytes and macrophages in the lymph nodes are fighting the infection and working to stop it from spreading. Such swellings are often called “swollen glands,” though lymph nodes—not glands—are swollen.

Lymphocytes also flow into the bloodstream and circulate throughout the body combating infection. Many lymphocytes find their way to areas just under the skin. There, they produce antibodies against bacteria and various substances that cause allergies.

Absorption of fats.

Lymphatic vessels in the wall of the intestine help the body absorb fat. These vessels are called lacteals. In the intestine, digested fats combine with certain proteins. The resulting particles enter the lacteals and give the lymph there a milky-white color. This milky-white lymph is called chyle. The chyle passes through the lacteals to the cisterna chyli, an enlarged area in the lower part of the thoracic duct. Then the chyle and other lymph fluids flow through the thoracic duct into the bloodstream. Absorption of fats thus differs from that of carbohydrates and proteins, which blood vessels absorb and transport to the liver.

Rejection of transplanted tissue.

Lymphocytes also take part in the body’s rejection of tissue that has been transplanted from one person to another. They react against transplanted tissue in the same way that they do against other foreign material—by producing antibodies. After a person has received a transplanted organ, doctors reduce antibody production by destroying lymphocytes. However, this destruction of the lymphocytes reduces the patient’s ability to fight infection.