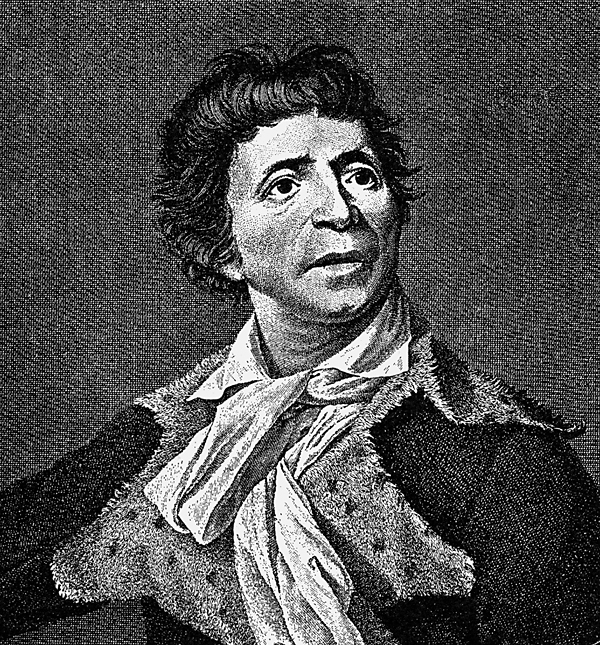

Marat, Jean-Paul, << mah RAH, zhahn pawl >> (1743-1793), was one of the most radical leaders of the French Revolution (1789-1799). He helped increase the violence of the period by demanding death for all opponents of the revolution.

Marat was born on May 24, 1743, in Boudry, Switzerland, near Neuchâtel. He became a physician and a writer. During the 1770’s and 1780’s, Marat wrote books on electricity, heat, light, and physiology, as well as on law and political theory. The French Academy of Sciences rejected Marat’s chief ideas, and Marat believed that officials of the academy had cooperated to keep him from winning the recognition he deserved.

Marat strongly supported the French Revolution, which began in 1789. He believed it would improve conditions, especially for the poor. Marat founded a newspaper, L’Ami du Peuple (The Friend of the People). The paper violently criticized those who opposed the revolution.

In August 1792, the people of Paris put King Louis XVI and his family in prison. Marat called for death for those who continued to support the king. Indirectly, he contributed to the violent mood of the public that led to the massacres in Paris in September. That month, bands of revolutionaries broke into the city’s prisons and killed over 1,000 prisoners, including priests and aristocratic supporters of the king.

Later in September, Marat was elected to the National Convention, a body that was writing a new constitution for France. He joined a group called the Jacobins, who demanded the king’s execution. Marat soon became the main target of moderate members of the convention, known as Girondists. They accused Marat of plotting against them and brought him to trial. He was acquitted and, in turn, called for the expulsion of Girondist leaders from the convention. They were expelled and then arrested in June 1793. On July 13 of that year, Marat was stabbed to death by Charlotte Corday, an aristocrat who supported the Girondists.

See also Corday, Charlotte; French Revolution.