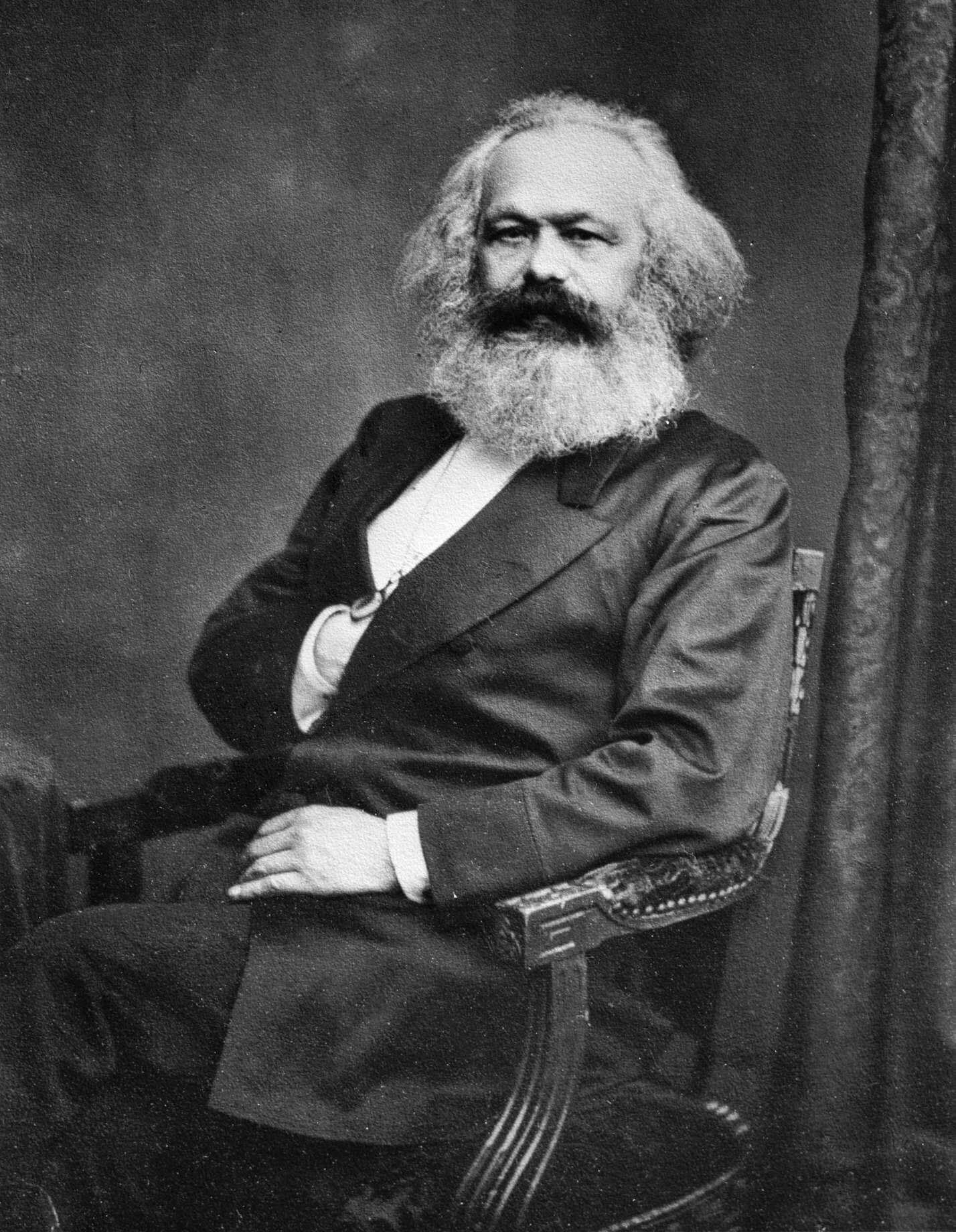

Marx, Karl (1818-1883), ranks among the most important thinkers of the 1800’s. Few writers in all of history rival him for his broad influence on world affairs. His writings helped form a foundation for the political and economic system known as Communism.

Marx predicted that capitalism would collapse in industrialized countries and that Communism would eventually take its place. He thought capitalism would end with a workers’ revolution against the owners of factories and other property used to produce goods and services. In the revolution, the workers would gain control of economic resources and the government.

In the 1900’s, Marx’s thinking shaped the policies of socialist and Communist governments in many countries. His ideas also influenced numerous academic fields, especially economics, history, and political science, even in capitalist nations.

Marx’s life

Childhood.

Karl Heinrich Marx was born on May 5, 1818, in the town of Trier, in what is now western Germany. At that time, the region was part of Prussia. Both Marx’s father, Heinrich, and his mother, Henrietta, were born into Jewish families. In fact, both of Marx’s grandfathers were rabbis. However, Marx’s father had converted to Lutheranism about a year before Karl’s birth. The conversion probably resulted from the enforcement of anti-Jewish laws by government authorities. But it also helped Marx’s father, a lawyer, advance in his career. The children in the family, including Karl, were baptized in 1824, and Marx’s mother converted the next year.

University education.

In 1835, Marx began studying law at the University of Bonn. The next year, he transferred to the University of Berlin. There, he switched his focus to philosophy. In Berlin, he became known as a critic of religion and of the Prussian government. He earned a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Jena in 1841. But his criticism of religion and the government ended his hopes for a job as a professor. The Prussians and especially Prussia’s royal family, who were deeply religious, controlled the jobs at most universities in the German-speaking world.

With an academic career closed to him, Marx turned to journalism, becoming an associate editor of a radical newspaper in Cologne called the Rheinische Zeitung. Prussian authorities opposed the paper because it often criticized the Prussian government.

Marriage and move to Paris.

In 1843, Marx married Jenny von Westphalen, the daughter of a German baron. Their marriage seemed happy. In times of crisis, Marx relied on his wife for both emotional and financial support. Also in 1843, the Prussian authorities stepped up their efforts against the Rheinische Zeitung. As a result, Marx and his wife left Prussia and moved to Paris. At that time, Paris was the home of many intellectuals and rebels from throughout the world. Marx soon became involved in their disputes and causes.

About this time, three key events happened in Marx’s life. First, he became involved in a workers’ movement that favored socialism as a solution to the problems of the poor. Second, he met and became friends with the German journalist Friedrich Engels. Marx and Engels were both active in the workers’ movement, and they established an intellectual partnership. Third, France became an ally of Prussia, and French authorities cracked down on immigrants who criticized the Prussian government. Because of the crackdown, Marx moved to Brussels, Belgium, in 1845. There, with Engels, he wrote his best-known work, the Communist Manifesto (1848).

In 1848, a parliamentary government came to power in Prussia. Marx then briefly returned to Cologne and his old journalism career. He edited another radical newspaper, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung. But the Prussian aristocracy soon regained control of the government.

Move to London.

In 1849, Marx fled to London. His wife’s financial resources became exhausted, and the couple fell into poverty. Engels gave Marx money during this period. Marx also tried to make ends meet by writing as an international correspondent for the New York Tribune and other newspapers.

In London in 1864, Marx founded the International Workingmen’s Association (later called the First International), an organization dedicated to improving the life of the working class. About this time, Marx also wrote his most ambitious work, Das Kapital (Capital) . He planned a four-volume work but completed only three volumes. Only the first was published during his lifetime, in 1867. Engels edited the second and third volumes after Marx died on March 14, 1883. They were published in 1885 and 1894.

Marx’s ideas

Early development.

As a university student, Marx was heavily influenced by the work of the German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel. The young Marx adopted many of Hegel’s ideas, including the notion that rational ideas were the driving force in history. In the early 1840’s, however, Marx began to move away from a strictly Hegelian philosophy. He rejected Hegel’s notion that rational ideas determined events and instead maintained the opposite, that material forces—the forces of nature and especially of human economic production—determined ideas.

In Paris in the 1840’s, Marx became interested in the ideas of French socialists, including Pierre J. Proudhon and Charles Fourier. A key issue among Paris intellectuals was the plight of the growing number of people who had been impoverished and dislocated by the Industrial Revolution, a period of rapid industrial growth that had begun in the 1700’s.

During the Industrial Revolution, most factory workers and miners in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and other countries were poorly paid and worked long hours under unhealthful and dangerous conditions. To Marx, older explanations for poverty did not seem to explain these new developments. For example, he rejected the arguments of the French socialists who claimed poverty resulted from the greed of the wealthy. He preferred the more scientific theories of British free-market thinkers, including Adam Smith and, especially, David Ricardo. Ricardo and Smith had argued that changes occur in society due to the automatic and irresistible forces of economic competition.

By the mid-1840’s, Marx had adopted the four basic elements of his philosophy: (1) Hegel’s idea that history progresses through a necessary series of conflicts; (2) materialism, which maintains that the physical world accounts for everything real; (3) socialism and its emphasis on public ownership of property used for economic production; and (4) the capitalist idea that market forces determine economic activity.

The

Marx’s most famous work, outlined what became known as Marxism. According to the Manifesto, which was published in 1848, industrial Europe and North America soon would experience economic and social collapse because of the unavoidable defects of capitalism. With such a collapse, the working class would use socialism to dismantle capitalism’s foundation of private property. The Manifesto invited industrial workers to join the International Workingmen’s Association, which called itself “communist.” The Manifesto also distinguished the working class from other groups, including middle-class business owners.

In 1848, revolutions occurred throughout Europe. But instead of being led by workers, many of them were nationalist, middle class, or even democratic in character. Nevertheless, they provided numerous readers for the Manifesto. As a result, Marx’s ideas quickly spread.

Das Kapital

later offered a theoretical explanation of how capitalism developed and how it would be transformed into Communism. In this work, Marx traced the origin of capitalism to the establishment of private productive property—that is, property used to produce goods and services. The owners of this property possessed and enjoyed more goods and services than they produced by their own labor. By contrast, the working class produced more goods and services than they would ever own or enjoy. In Das Kapital, Marx argued that this division of classes created a conflict that drove civilization through various stages of history.

Marx thought that all civilizations throughout history had inevitably experienced class conflict between workers and the owners of productive property. In ancient societies, according to Marx, these two classes were the masters and the slaves. In the Middle Ages, they were the lords and the vassals. In the industrial, capitalist world, they were the middle-class owners of productive property and the workers. Marx called the middle-class owners the bourgeoisie << boor zhwah ZEE >> and the workers who did the actual labor the proletariat.

Unlike many other social critics during the Industrial Revolution, Marx did not see capitalism as a moral problem. For example, the English novelist Charles Dickens and the French writer Victor Hugo saw child labor, extremes of wealth and poverty, and other aspects of capitalism as immoral. Marx, however, saw capitalism as a necessary stage in resolving workers’ problems. He thought that under capitalism, those problems took their purest form and thus would result in a workers’ revolution that would lead to Communism.

Marx believed that the boom-and-bust business cycles of capitalism would help trigger the revolution. According to him, occasional overproduction created more goods and services than owners could sell. Forced by competition to be efficient, owners had to either fire workers or slide into the ranks of the proletariat themselves. But with fewer workers receiving wages, fewer people could buy and consume products. As a result, the problem of overproduction became more serious. According to Marx, this spiraling process would eventually result in a swelling of the working class and a shrinking of the owner class until the system broke down.

The working class would then revolt and seize control of the government. A workers’ dictatorship would use the government to end private ownership of productive property. Eventually, social classes would disappear. Even government, no longer needed to enforce public ownership of property, would “wither away.” A true Communist society would then have been achieved.

Marx’s influence

Marx’s thinking had its greatest impact among Communists. The government and economy of the Soviet Union, the world’s most powerful Communist country, was based on Marxist doctrines as uniquely interpreted by V. I. Lenin. The Soviet Union was formed in 1922, and Lenin became its first dictator. The official principles of the Soviet Union and many other Communist nations became known as Marxism-Leninism. Other Communist countries included the nations of Eastern Europe—most of which the Soviet Union controlled—as well as China, Cuba, North Korea, and Vietnam.

Marx’s thinking also influenced non-Communist socialists. But many of them disagreed with him on certain points. For example, many moderate socialists rejected his idea that socialism had to be achieved by a revolution. They believed instead that socialism could be established gradually by working within democratic institutions and by forming an alliance with the middle class.

In 1991, the Soviet Union broke apart into a number of separate countries, most of which rejected Communism. About the same time, many Eastern European countries adopted non-Communist governments. Also in the late 1900’s, China and other Communist nations introduced capitalist elements into their economies. Many people saw these events as proof that Marx’s predictions about capitalism and Communism had been wrong.

However, many of Marx’s admirers argue that the policies of Communist governments have had little in common with Marx’s thinking. For example, they point to Marx’s claim that, under true Communism, the government would wither away. In the Soviet Union and other Communist countries, the government showed no signs that it would ever do so.

Also, in spite of the decline of Marx’s influence on government, his ideas still affect notions of social conflict, historical development, and class throughout the world. In addition, much of today’s criticism of capitalism and free-market theories still reflects the impact of Marx’s writings.