Monroe, James (1758-1831), is best remembered for the Monroe Doctrine, proclaimed in 1823. This historic policy warned European countries not to interfere with the independent nations of the Western Hemisphere.

Monroe became president after more than 40 years of public service. He had fought in the Revolutionary War in America (1775-1783). During the first years after independence, he had served in the Virginia Assembly and in the Congress of the Confederation. He later became a United States senator; minister to France, Spain, and the United Kingdom; and governor of Virginia. During the War of 1812, he served as secretary of state and secretary of war at the same time.

In appearance and manner, Monroe resembled his fellow Virginian, George Washington. He was tall and rawboned, and had a military bearing. His gray-blue eyes invited confidence. Even John Quincy Adams, who criticized almost everyone, spoke well of Monroe.

At his inauguration, Monroe still wore his hair in the old-fashioned way, powdered and tied in a queue at the back. He favored suits of black broadcloth with knee breeches and buckles on the shoes. To the people, he represented the almost legendary heroism of the generation that led the country to independence.

As president, Monroe presided quietly during a period known as “the era of good feeling.” He looked forward to America’s glorious future, the outlines of which emerged rapidly during his presidency. The frontier was moving rapidly westward, and small cities sprang up west of the Mississippi River. Monroe sent General Andrew Jackson on a military expedition into Florida that resulted in the acquisition of Florida from Spain. Rapidly extending frontiers soon caused Americans to consider whether slavery should be permitted in the new territories. The Missouri Compromise “settled” this problem in the Louisiana Purchase area by setting definite limits to the extension of slavery there.

Early life

Boyhood.

James Monroe was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on April 28, 1758. His father, Colonel Spence Monroe, came from a Scottish family that had settled in Virginia in the mid-1600’s. The family of his mother, Elizabeth Jones Monroe, came from Wales, and also had lived in Virginia for many years. James was the eldest of four boys and a girl.

James studied at home with a tutor until he was 12 years old. Then his father sent him to the school of Parson Archibald Campbell. The boy had to leave home early in the morning and tramp through the forest to reach Campbell’s school. He often carried a rifle and shot game on the way. At the age of 16, James entered the College of William and Mary. However, the stirring events of the Revolutionary War soon lured him into the army.

Soldier.

Although only 18, Monroe was commissioned a lieutenant. He soon saw action, fighting at Harlem Heights and White Plains in New York in the fall of 1776. His superior officers praised Monroe for gallantry in the Battle of Trenton, N.J., where he was wounded in the shoulder. During the next two years, he fought at Brandywine and Germantown in Pennsylvania and Monmouth in New Jersey.

In 1778, Monroe was promoted to lieutenant colonel and sent to raise troops in Virginia. He failed in his mission, but it greatly influenced his future career. It brought him into contact with Thomas Jefferson, then governor of the state. Monroe began to study law under Jefferson’s guidance, and became a political disciple and lifelong friend of his teacher.

Political and public career

Monroe began his public career in 1782, when he won a seat in the Virginia Assembly. In 1783, he was elected to the Congress of the Confederation, where he served three years (see Congress of the Confederation). Monroe did not favor a highly centralized government. But he supported moderate measures intended to let Congress establish tariffs. Monroe worked to give pioneers the right to ship goods down the Mississippi River through Spanish territory. He also helped Jefferson draft laws for the development of the West. Two hurried trips to the West had left Monroe unimpressed with its beauty or fertility. But he still believed the region would be important for the country’s future growth.

State politics.

In 1786, Monroe settled down to practice law in Fredericksburg, Virginia. But politics drew him like a magnet. He ran for the Virginia Assembly and won easily. He remained in the Assembly four years.

In 1788, Monroe served in the convention called by Virginia to ratify the United States Constitution. His distrust of a strong federal government aligned him with Patrick Henry and George Mason, who opposed the Constitution. But Monroe offered only moderate opposition, and he gracefully accepted ratification.

Monroe’s family.

In 1786, Monroe married 17-year-old Elizabeth Kortright (June 30, 1768-Sept. 23, 1830), the daughter of a New York City merchant. The couple had two daughters, Eliza Kortright and Maria Hester, and a son (probably named James Spence), but the boy died as an infant. Monroe’s admiration for Jefferson became so strong that in 1789 he moved to Charlottesville, Virginia. There he built Highland (now called Ash Lawn-Highland), not far from Jefferson’s estate, Monticello.

U.S. senator.

Monroe ran against James Madison for the first United States House of Representatives but lost. In 1790, the Virginia legislature elected him to fill a vacancy in the U.S. Senate. As a senator, Monroe aligned himself with Madison and with Jefferson, then secretary of state, in vigorous opposition to the Federalist program of Alexander Hamilton. Assisted by such leaders as Albert Gallatin and Aaron Burr, the three Virginians founded the Democratic-Republican Party. This party developed, some historians believe, into the modern Democratic Party (see Democratic-Republican Party).

Opposition to Washington.

In 1794, President George Washington appointed Monroe minister to France. The president knew that Monroe opposed many administration policies, but he needed a diplomat who could improve relations with the French. He also knew that Monroe strongly admired France.

During talks in France, Monroe criticized the Jay Treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom as “the most shameful transaction I have ever known.” Furious, Washington recalled Monroe in 1796. See Jay Treaty.

Upon his return, Monroe became involved in a bitter personal dispute with Hamilton. The quarrel resulted from the publication of materials that slandered Hamilton. Monroe was blamed but denied responsibility. Hamilton eventually dropped his charges.

Diplomat under Jefferson.

In 1799, Monroe was elected governor of Virginia. In this post, he played an important part in preserving democratic processes during the tense years following passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts, which made it a crime to criticize the president or Congress falsely and maliciously. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson sent Monroe to Paris to help Robert R. Livingston negotiate the purchase of New Orleans. By the time Monroe reached France, Napoleon had offered the astonished Livingston the entire Louisiana Territory. Monroe urged Livingston to accept the offer without waiting to consult Jefferson, and they arranged for the treaty. See Louisiana Purchase.

Jefferson was pleased with Monroe’s initiative and sent him to Madrid to help Charles Pinckney purchase the Floridas from Spain. They failed, but Jefferson still had confidence in Monroe. The president named him minister to the United Kingdom. In 1806, however, Monroe helped conclude a trade treaty that was so unsatisfactory that Jefferson refused to submit it to the Senate.

Monroe felt his usefulness in London had ended and returned home in 1807. He became a reluctant candidate for the nomination to succeed Jefferson as president. But Madison won the nomination and the presidency. Monroe served in the Virginia Assembly until he again was elected governor in 1811.

Secretary of state.

Monroe resigned as governor after about three months to accept President Madison’s appointment as secretary of state. At that time, U.S. relations with the United Kingdom and France were strained. The British navy had been taking American sailors of British birth and impressing (forcing) them back into British service. In addition, the United Kingdom and France had set up naval blockades against each other that greatly interfered with U.S. shipping. Monroe soon concluded that these problems could not be resolved peacefully.

At the beginning of the War of 1812, Monroe was eager to take command of the Army. But Madison convinced him to stay in the Cabinet. Secretary of War John Armstrong was forced to resign in 1814 because of neglect of duty during the burning of Washington, D.C. Madison asked Monroe to become secretary of war while continuing as secretary of state. Monroe held both offices for the rest of the war. After he took over the War Department, American armies won several brilliant victories. These triumphs greatly increased Monroe’s popularity. See War of 1812.

In 1816, while still secretary of state, Monroe was elected president of the United States. He received 183 electoral votes to 34 for Senator Rufus King of New York, the Federalist candidate. Monroe’s running mate was Governor Daniel D. Tompkins of New York.

Monroe’s administration (1817-1825)

The years of Monroe’s presidency are generally known as “the era of good feeling.” The Federalist Party gradually disappeared after the election of 1816, and most people supported the Democratic-Republican Party. The country prospered because of fast-growing industries and settlement of the West. A depression in 1818-1819 caused only a temporary setback.

“The American System”

was the chief issue of Monroe’s first term. House Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky advanced this plan. The American System proposed to strengthen the nation in two ways: (1) construction of new roads and canals to open the West, and (2) enactment of a protective tariff to encourage Northern manufacturers and develop home markets.

Monroe distrusted the American System because he doubted that the federal government had the power for these activities. Monroe studied the program during a 31/2-month tour of the North and West. But this trip did not change his “settled conviction” that Congress did not have the power to build roads and canals.

Clay continued his fight and finally won Congress over to his side. In 1822, Monroe vetoed a bill providing for federal administration of toll gates on the Cumberland Road. He urged a constitutional amendment to give Congress the power to promote internal improvements. In 1824, Monroe signed the Survey Act, which planned improvements in the future.

Clay had more success in pushing through the protective tariff, the second part of his American System. Congress had already raised tariff rates in 1816, and it further increased the duty on iron in 1818. In 1824, Congress raised tariff rates in general.

Life in the White House.

The British had burned the White House during the War of 1812, and the mansion had not been rebuilt when Monroe took office. The new president maintained his residence on I Street, near 20th Street, for nine months. On New Year’s Day, 1818, President and Mrs. Monroe held a public reception marking the reopening of the White House.

Monroe decided to follow strict etiquette in the White House. Partly because of ill health, Mrs. Monroe received only visitors to whom she had sent invitations. She refused to pay calls, sending her elder daughter, Eliza Hay, in her place. Soon all Washington buzzed about the “snobbish” Mrs. Monroe.

As time passed, the public realized that Mrs. Monroe had followed the president’s wishes in establishing protocol. During Monroe’s second term, her Wednesday receptions became popular. The visit of the Marquis de Lafayette on New Year’s Day, 1825, added a touch of splendor to the last months of Monroe’s term.

Beginnings of sectionalism.

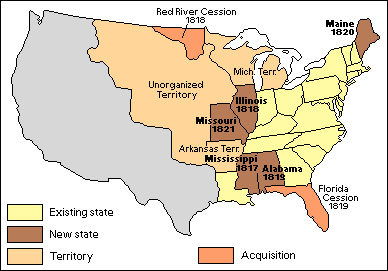

In 1818, Missouri applied for admission to the Union as a slave state. The House of Representatives aroused anger in the South by passing a bill to admit Missouri with the provision that no more slaves could be brought into the state. The Senate defeated this provision, and Congress eventually agreed on a plan known as the Missouri Compromise. Under the plan, Congress admitted Maine to the Union as a free state and authorized Missouri to form a constitution so it could then apply for statehood. Congress permitted slavery in Missouri but banned it from the rest of the Louisiana Purchase region north of the southern boundary of Missouri. Monroe avoided interfering with these debates. But he said he would not sign a bill placing any special restraints on Missouri’s admission to the Union. See Missouri Compromise.

War with the Seminole.

Since the War of 1812, Americans in Georgia had been harassed by bands of Indians in Spanish Florida, partly because the Americans were not honoring their treaties with the Indians. In 1817, fighting broke out between the Seminole Indians and settlers in southern Georgia. Monroe ordered Major General Andrew Jackson to attack the Indians. Jackson chased them into the Everglades of Florida. Then he captured Pensacola, Spanish Florida’s capital.

Jackson’s easy conquest convinced the Spanish that they could not defend Florida. In 1819, they agreed to give Florida to the United States in return for the cancellation of $5 million in American claims against Spain.

Diplomacy.

Monroe’s administration marked one of the most brilliant periods in American diplomacy. The Rush-Bagot Agreement, signed with the United Kingdom in 1817, limited naval forces on the Great Lakes. In 1818, the United Kingdom agreed to the 49th parallel as the boundary between the United States and Canada from Lake of the Woods on the Minnesota-Ontario border as far west as the Rocky Mountains. The British also consented to joint occupation of the Oregon region. American diplomats persuaded Spain to give up its claims to Oregon in 1819, and the Russians agreed to a similar pact in 1824.

Reelection.

In the election of 1820, Monroe was unopposed. He received every vote cast in the Electoral College but one. William Plumer, an elector from New Hampshire, cast his vote for John Quincy Adams.

The Monroe Doctrine.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Spaniards had become deeply involved in European affairs and took little interest in their American colonies. Most of the colonies took advantage of this situation and declared independence from Spain. The Latin-American revolutions aroused great sympathy in the United States. As early as 1817, Henry Clay had begun a campaign for recognition of these new countries. Over the period of time from 1822 to 1824, Monroe finally recognized their independence. In December 1823, the president proclaimed the historic Monroe Doctrine in a message to Congress. This doctrine has remained a basic American policy ever since.

The era of good feeling ended before Monroe finished his second term. Unlike the situation which followed the retirement of Jefferson and Madison, there was no outstanding figure who was the overwhelming choice to become the next president. Four men fought for the office. None won a majority of the votes, and the House of Representatives chose John Quincy Adams. See Adams, John Quincy (Election of 1824).

Later years

Monroe retired to Oak Hill, his estate near Leesburg, Virginia. He served for five years as a regent of the University of Virginia. In 1829, he became presiding officer of the Virginia Constitutional Convention. His wife died on Sept. 23, 1830, and was buried at Oak Hill. Long public service had left Monroe a poor man, and he was too old to resume his law practice. Late in 1830, his financial distress forced him to move to New York City to live with his daughter. Monroe died there on July 4, 1831. In 1858, his remains were moved to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. His law office in Fredericksburg has been preserved as a memorial.