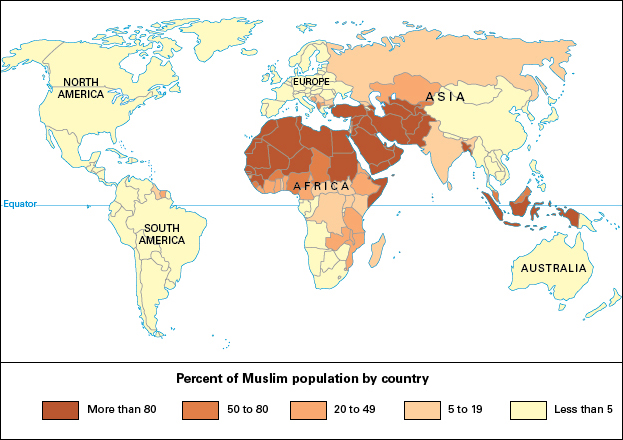

Muslims << MUHZ luhmz >>, sometimes spelled Moslems, are people who practice the religion of Islam. The Prophet Muhammad first preached the religion in the A.D. 600’s. Islam originated with the Arabs in the Middle East. By the mid-700’s, Muslims had built an empire that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the borders of China.

Before Muhammad

Abraham and Ishmael.

According to Muslim tradition, the history of the Muslims begins with the Biblical story of Abraham and Ishmael. Both Jews and Arabs regard Abraham, who may have lived between about 1800 and 1500 B.C., as the father of their people. Abraham’s wife Sarah was past childbearing age, so she gave her handmaiden Hagar to her husband as a second wife. Hagar bore a son, the prophet Ishmael. Later, Sarah and Abraham also had a son, the prophet Isaac. After Isaac’s birth, Sarah pressured Abraham into expelling Hagar and Ishmael from his house.

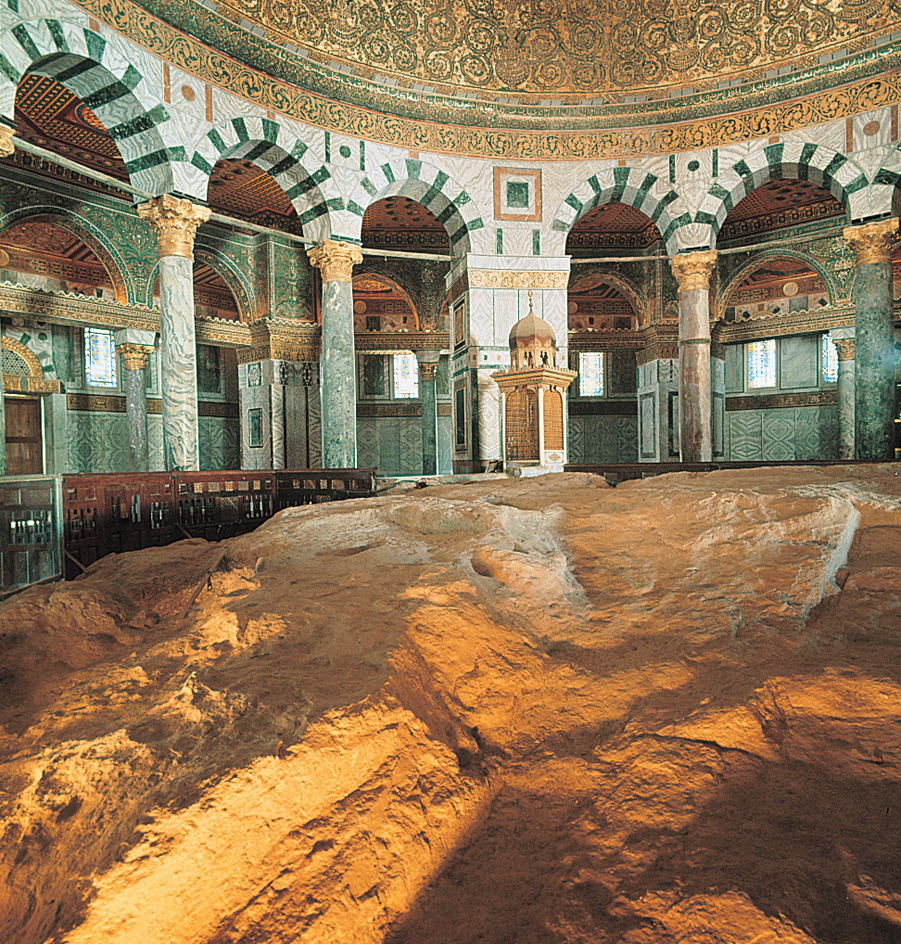

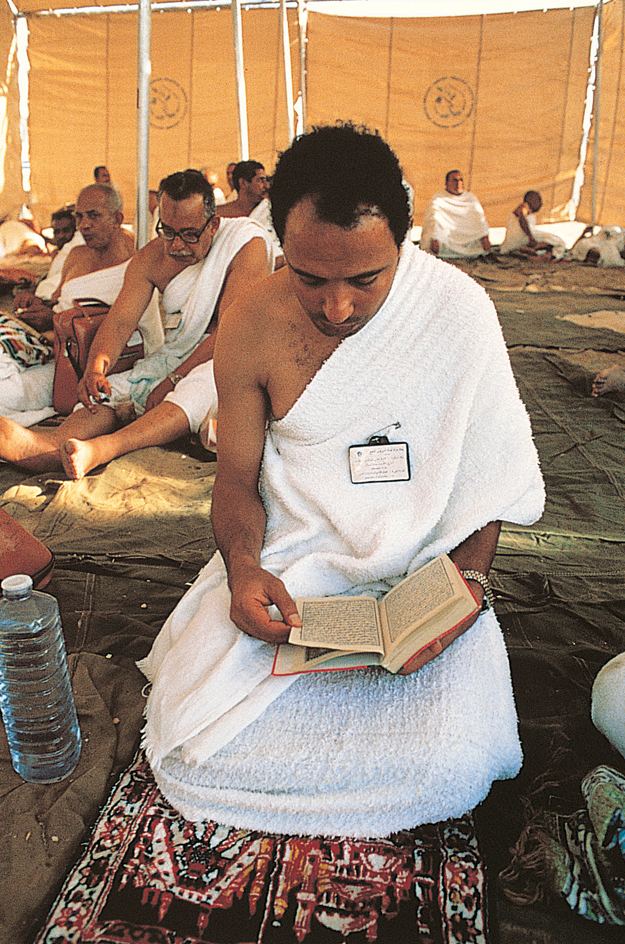

Muslim tradition teaches that Hagar and Ishmael traveled to a valley in western Arabia called Bakka, which is now the city of Mecca. There they found a sacred well, called Zamzam, that sustained Hagar and Ishmael with its water. When Ishmael reached adulthood, Abraham visited him. Near the well of Zamzam, the two prophets built the Ka`ba as a temple to Allah (God). In the eastern corner to the Ka`ba, they placed the Black Stone, which Muslims believe was brought to them by an angel. The Ka`ba became the holiest shrine of Islam. Muslims who perform the pilgrimage to Mecca walk around the Ka`ba seven times. Many of them try to kiss or touch the Black Stone.

The Arabs before Islam

included nomads, traders, farmers, and town-dwellers. They belonged to many tribes and had many religions. Most Arabs worshiped multiple gods. Arab deities included the goddesses al-Lat, al-Uzza, and Manat, who were important in the Mecca region. The supreme deity of the Arabs was a remote heavenly god whom they called Allah, which means the god. The Arabs believed he was the creator of the universe, the bringer of life and rain. He was the god on whom people called in times of great danger or distress.

Muhammad

The Prophet Muhammad was born in Mecca in about A.D. 570. At that time, Mecca was a major commercial center controlled by an Arab tribe called the Quraysh << koo RAYSH >>, who had abandoned the traditional Arab nomadic way of life and become merchants. The Quraysh were divided into clans, including the Banū Umayyā << BA noo oo MAY ah >> and the Banū Hashim << BA noo HA shihm >>. The Banū Umayyā were the wealthiest and most powerful clan in Mecca. The Banū Hāshim, into which Muhammad was born, were responsible for supplying food and drink for pilgrims who came to Mecca to visit the Ka`ba.

Muslims believe that in about 610, Muhammad began to receive revelations from Allah. For Muslims, the greatest miracle of Muhammad’s prophethood was the Qur’ān << ku RAHN or ku RAN >>, sometimes spelled Koran, the holy book of Allah’s revelations. The revelation of the Qur’ān to Muhammad took place over a period of about 22 years. Muhammad dictated the verses to his followers, who wrote them down. Several of these “Scribes of Revelation” became important Muslim leaders. They included AlĪ ibn AbĪ Tālib << ah LEE IHB uhn ah BEE tah LEEB >>, Uthmān ibn Affān << ooth MAN IHB uhn al FAHN >>, and Mu`āwiyah ibn AbĪ Sufyān << moo AH wee ya IHB uhn ah BEE soo FEE yahn >>.

Some years after Muhammad’s death, when Uthmān was caliph—that is, a Muslim leader who succeeded Muhammad—he formed a committee to collect these revelations into a single volume. The committee’s work produced a master copy of the Qur’ān that became the model for the book used by Muslims today.

The people of Mecca persecuted the early Muslims because Muhammad had rejected their gods and because he condemned wealthy Meccans for not helping those in need, such as widows, orphans, and the poor. He also condemned their practice of killing female infants. Eventually, Muhammad and his followers were forced to abandon Mecca. In 622, a delegation from Medina (then called Yathrib), north of Mecca, invited Muhammad to come to that city and act as arbitrator (judge) between its feuding tribes. Muhammad’s journey from Mecca to Medina is called the Hijra, also spelled Hijrah or Hegira. Muslims consider it so important that the Islamic calendar begins with the year of the Hijra. In Medina, Muhammad and his companions laid the foundations of Islamic society. That society is based on Qur’ānic teachings as exemplified by the Sunnah and the Sharī`a (also spelled Sharī`ah). The Sunnah is the example of the Prophet’s sayings and behavior. The Sharī`a is the code of Islamic law.

To defend Islam from its enemies, Muhammad launched several military campaigns against Mecca and other parts of the Arabian Peninsula. Mecca surrendered to him in 630. In 631, delegations from many tribes and clans in Arabia swore to give up the worship of multiple gods and submit to Muhammad’s authority. Muhammad died in Medina in 632.

The early caliphs

After the Prophet died, a dispute arose over his successor. On one side were members of the tribes of Medina, who wanted one of their own leaders to rule the town again. Another side included Muhammad’s friend Abū Bakr, along with Umar ibn al-Khattāb << OO mahr IHB uhn al kah TAHB >>, one of the most powerful of the early Muslims. After the death of his first wife, Muhammad had married both Abū Bakr’s daughter Ā`ishah << ah YEE shah >> and Umar’s daughter Hafsah. They were the most influential of the Prophet’s wives. In addition, some Muslims thought Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, Alīibn Abī Tālib, who had adopted Islam as a child and was like a son to the Prophet, should succeed him as leader. On the day of Muhammad’s death, Umar acknowledged Abū Bakr as caliph, and soon others followed his example. Umar said he took the action to prevent divisions in the Muslim community.

Abū Bakr

ruled as caliph in Medina for two years. He took political charge of the Muslim community and led prayers in the Prophet’s place. However, he refused to assume Muhammad’s role as the interpreter of Islamic doctrine. He left interpretation to the collective judgment of the Prophet’s companions. Abū Bakr’s example in referring religious decisions to community leaders eventually formed the basis of the Sunni << SOON ee >> division in Islam. The followers of Sunni Islam are called Sunnis.

Abū Bakr faced revolts by Arabian tribes against the authority of the Islamic state. Some tribes even put forth their own prophets. Within about a year, however, Abū Bakr put down these revolts and the tribes accepted his authority.

Umar.

In 634, Abū Bakr died, naming Umar to succeed him as caliph. Umar’s 10-year rule became a great period of Islamic expansion. First, he sent Qur’ān reciters to the tribes of Arabia to teach them Islam. Next, he embarked on the full-scale conquest of the Middle East. During this period, Islam was largely a religion of the Arabs, and Umar concentrated on spreading Islam among the tribes of Syria and Iraq. Most Arabs converted to Islam at this time.

By the end of Umar’s caliphate in 644, the Muslims had conquered Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and most of Iraq. Because of the great increase in the number of people under their rule, the Muslims set up an administration to govern the new territories. They sent Muslim soldiers and their families to settle in strategically located towns, which rapidly grew into major cities. Each town centered on a main mosque (Muslim place of worship) and was ruled by the provincial governor. Soldiers and other Muslims each received a payment from a share of the booty taken during conquests and taxes from conquered lands. The payments varied depending on how long each person had been a Muslim. Thus, the earliest converts had great political power and often made fortunes.

Uthmān.

Just before Umar died, he appointed a committee to choose his successor. When the committee asked Alī ibn Abī Tālib to become caliph and follow the rulings of his predecessors, he refused. He claimed that he knew more than the previous caliphs about Muhammad’s original views and intentions. Uthmān ibn Affān, another son-in-law of the Prophet, accepted the conditions that had been offered to Alī and was appointed caliph.

Under Uthmān, the Muslims completed the conquest of Iran and began to spread across northern Africa from Egypt. But political conflicts broke out and marked the end of Muslim political and religious unity. Despite Uthmān’s piety, his enemies accused him of favoritism and a love of wealth and luxury. Political corruption and stricter economic policies in the provinces caused the Muslims of Egypt to revolt against their governor, Uthmān’s foster brother. Uthmān’s half-brother, who was the governor of Kufa (also spelled Al Kufah) in southern Iraq, disgraced himself by appearing drunk in public.

In 656, delegations from Egypt and Iraq arrived in Medina to protest Uthmān’s policies. Many of Medina’s citizens, including Muhammad’s widow Ā`ishah and his son-in-law Alī, also opposed Uthmān. But Alī had no desire to start a rebellion. When Uthmān appealed to him to help settle the dispute, he did so, but he asked the caliph to change his policies. Ali’s attempt at a settlement failed, and protesters killed Uthmān. Immediately afterward, a delegation went to Alī and proclaimed him caliph. At first, he refused because Uthmān had been murdered. But he consented after other delegations from Medina and the provinces urged him to accept.

Alī.

The caliphate of Alī marks the beginning of the Shī`ah division of Islam. As the closest living relative of Muhammad, Alī claimed a unique understanding of the Prophet’s teachings. Alī’s followers, the Shī`ites, considered him the only true imam (Muslim leader). After Alīi’s death, his sons and descendants led the Shī`ites as imams. The Shī`ites agreed with most Muslims on matters of doctrine. However, they also felt that their imams, as the descendants of Muhammad, had inherited his authentic teachings.

When Alī accepted the caliphate, several Muslim leaders opposed him. They included Muhammad’s widow Ā`ishah and Muawiyah ibn Abi Sufyan, the governor of Syria and Uthmān’s cousin. From this point, Medina no longer served as the capital of the Islamic state. Alī moved to Kufa, the community in Iraq where most of his supporters lived. Ā`ishah and her allies moved to Basra, also in Iraq. In 656, Alī and Ā`ishah fought the Battle of the Camel, the first conflict of Muslim against Muslim. Alī won the battle, named for the camel that carried Ā`ishah.

Alī next turned against Mu`awiyah, who demanded that Alī produce Uthmān’s assassins or be considered an accomplice in the murder. In 657, the armies of Alī and Mu`awiyah fought at Siffin, near the Euphrates River in northern Syria. During the battle, soldiers in Mu`awiyah’s army raised pages of the Qur’ān on their spears and called for arbitrators to settle the conflict peacefully. Alī reluctantly agreed and the battle ended indecisively. Many of Alī’s followers opposed arbitration and turned against him. These followers were called Kharijites, meaning secessionists. They make up the third major division in Islam, after the Sunnis and Shī`ites.

The Kharijites rejected both Mu`awiyah and Alī. They felt that the best Muslim should be caliph, even if that person were a slave. In 658, Alī fought the Kharijites at Nahrawan in central Iraq. He won the battle, but many faithful Muslims were killed in the fighting. As a result, more people turned against Alī. Alī refused to step down as caliph. In 661, he was murdered by a Kharijite assassin seeking revenge for Nahrawan.

The Muslim empire

The Umayyads.

In 661, following the death of Alī, Mu`awiya became caliph and founded the Umayyad << oo MY ad >> caliphate. He made Damascus his capital. Under the Umayyads, the Islamic state became an imperial power, much like its rival, the Byzantine Empire. When choosing ruling officials, the Umayyads preferred Arabs over their non-Arab subjects. Under the Umayyads, the Muslims extended their conquests into Afghanistan and central Asia in the east and across northern Africa and into Spain in the west. Their main source of power was an Arab army based in Syria. This army swore personal loyalty to the caliph and acted as his bodyguard. Administratively, the Umayyads adopted many of the customs and institutions of the Byzantine Empire and of the Sasanian Empire, which had ruled Persia until the Muslim conquest.

In 680, Muawiyah died and was succeeded by his son Yazīd. Yazīd became notorious for corruption and misrule. The inhabitants of Medina refused to recognize Yazīd. In addition, Alī’s son Husayn, also called Husayn ibn Alī, rose against Yazīd. Husayn set off toward Kufa to gather support, but the Kufans were not able to help him. The Umayyads massacred Husayn and his small band of followers at Karbala in southern Iraq. This violence against the Prophet’s family shocked the Muslim world.

In 684, Yazīd’s cousin Marwān ibn al-Hakam, a former aide of Uthmān’s, succeeded to power in Syria. Marwān’s son, Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān, was proclaimed caliph in 685 and began the second phase of Umayyad rule. The later Umayyads faced a long series of revolts. Kharijites, Shī`ites, and other rebels agitated against them in the name of Islam. They advocated a return to the religion as it had been practiced by Muhammad and his companions.

The Abbāsids.

By the mid-700’s, important changes had occurred in Muslim society. An increasing rate of conversion to Islam, combined with intermarriage between Arabs and non-Arabs, had transformed the makeup of the Muslim population. For the first time, non-Arab Muslims outnumbered Arab Muslims in many regions. Many of the Kharijite and Shī`ite rebels against the Umayyads were non-Arab converts. In northern Africa, the Kharijites were mainly Berbers. In eastern Iran, many Kharijites and Shī`ites were Persian. Such new Muslims demanded equality with Arabs. The new Muslims called for a society in which each Muslim would have the same privileges and be subject to the same taxes, regardless of ethnic background. Religious scholars, who sought a return to a higher standard of piety, supported them.

The Abbāsids << uh BAS ihdz >> took up the cause of the new Muslims. The Abbāsids were descended from Muhammad’s uncle al-Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib. At first they joined forces with the Shī`ites, claiming that the most qualified member of the Prophet’s family should be caliph. The Abbāsids eventually dominated the anti-Umayyad movement. The Abbāsids called for revenge against the Umayyads for their treatment of Muhammad’s family. They conquered the Umayyads in 750, after a struggle lasting only three years. When some descendants of Alī claimed that one of them should hold the office of caliph, the Abbāsids suppressed them and their supporters.

From 750 to the mid-800’s, the Abbāsids transformed the Islamic state into an empire that blended many cultures and was ruled by an absolute monarch. The caliph continued to uphold the Sunnah of the Prophet and the Islamic Sharī`a. The Abbāsid caliph lived in splendid isolation and surrounded by thousands of officials and slaves. Only the most privileged were allowed to speak with him.

The capital of the Abbāsids was Baghdad in central Iraq. The caliph Abū Ja`far al-Mansūr had established the city in 762. At the heart of Baghdad was a huge administrative complex called the City of Peace. Beyond its walls stretched Baghdad and its suburbs, with more than a million inhabitants.

The Abbāsid Empire was a highly centralized monarchy, the greatest since the Roman Empire. It drew support from one of the largest and most integrated economic systems known until modern times. Through the Persian Gulf flowed the products of east Africa, Arabia, India, Southeast Asia, and China. Across the desert from Syria and down the Euphrates River came goods from northern Africa, Egypt, and the Mediterranean. To Muslim scholars and historians of this period, Baghdad was the center of the world.

During the Abbāsid period, the Islamic arts and sciences flourished. Several schools of Islamic law formed during this period. Study of the Qur’ān and of Arabic grammar developed. Around 815, the caliph Ma`mun created a research library called the House of Wisdom. A staff translated the works of Plato, Aristotle, and other Greek philosophers into Arabic. These translations stimulated the development of an Islamic philosophical tradition that played a major role in reintroducing many important works and ideas from Greek philosophy into western Europe.

Sufism (Islamic mysticism) also flourished during the Abbāsid period. Unlike the Shī`ites and Kharijites, the Sufis do not make up a separate division of Islam. Most Sufis are Sunni Muslims. They view Sufism as a school of thought within mainstream Islam. Most Sufis follow the Sharī`a closely and differ from other Muslims only in their desire to create a closer personal relationship with Allah.

The fall of the Abbāsids.

As a highly centralized monarchy, the Abbāsid Empire lasted little more than 100 years. Its authority never became fully established in the Islamic west. In 756, Abd al-Rahmān, an Umayyad prince who had escaped to Spain, founded a second Umayyad line of rulers that lasted until 1031. In the 780’s, Idrīs ibn Abd Allah, a descendant of Hasan ibn Alī, fled from Abbāsid persecution and created an independent kingdom in Morocco. Hasan was a son of Alī. In the 800’s, the Abbāsid governors of Tunisia and Egypt broke away from Baghdad and formed their own states.

From 929 to 1031, there were three competing caliphates at one time: the Abbāsids in Iraq; an Umayyad caliphate in Spain; and the Fātimids in northern Africa and, from 969, in Egypt. By this time, the Abbāsids ruled over the Muslim world in name only. From the mid-900’s until the Mongols captured Baghdad in 1258, most of the caliphs were puppet rulers, serving at the whim of military dictators. The blending of many cultures within Islam had led to the development of multiple centers of power and culture in the Muslim world. Such diversity of the Muslim world continues today.

The spread of Islam

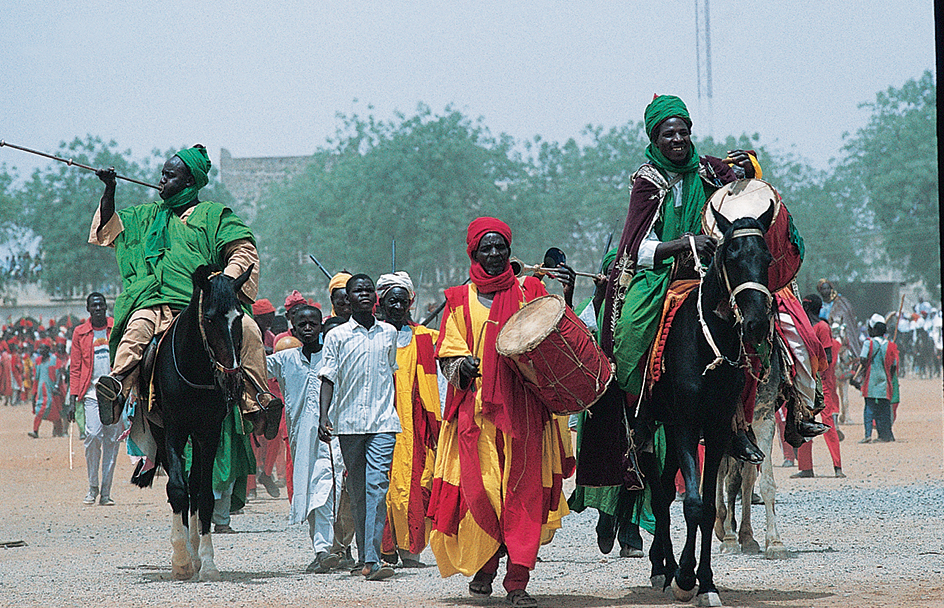

The Mongols killed the last Abbāsid caliph in 1258 and captured Baghdad, but the vitality of the Muslims did not diminish. Socially and culturally, the Muslim world became more diverse than ever. In west Africa and what are now Malaysia and Indonesia, Muslim merchants and scholars introduced Islam and converted kings, who made Islam the state religion. In China, the Muslim population also grew from communities of merchants. In Africa south of the Sahara, large-scale conversions began in the 1400’s. Most of these conversions resulted from trade and personal contact rather than conquest.

Muslim power reached a new height in the 1500’s. By that century, the Muslims had established three powerful empires: the Ottoman Empire, which began in what is now Turkey; the Safavid dynasty in Iran; and the Mughal Empire in India.

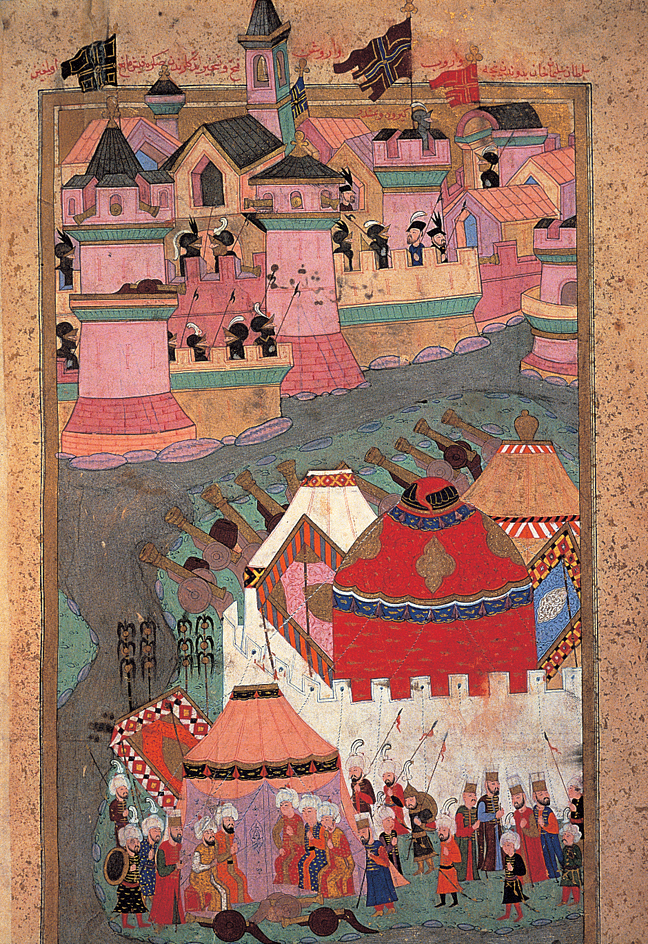

The Ottoman Empire

lasted from about 1300 to 1922. The Ottomans were named after Osman I, a Turkish chieftain who founded a state in Anatolia (now Turkey) in the late 1200’s. The Ottomans claimed to be the champions of Sunni Islam. In 1453, Sultan Mehmet II conquered Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. The city, now called Istanbul, became the capital of the Ottoman Empire.

By 1600, the Ottoman Empire formed a crescent around the Mediterranean extending from Hungary in eastern Europe through Palestine and Egypt to Algeria in northern Africa. Under the reign of Sultan Suleyman I in the 1500’s, the Muslim world achieved its greatest level of unity since the time of the Abbāsids. Under the Ottomans, many cultures maintained their identities within Muslim society. The Ottoman sultans were Turkish, but the generals, admirals, and administrators of the Ottoman Empire came from throughout the Mediterranean world. Many Ottoman aristocrats were skilled in the arts, languages, and literature, and they set the standard for culture in the Muslim world.

Many Ottoman officials came from Christian families. Each year, recruiting teams collected boys from eastern Europe. The youths were taken to Istanbul, converted to Islam, and educated. Legally, they became slaves of the sultan and were supposed to be loyal only to him. The most physically active boys became “Men of the Sword” and served in the Janissary Corps, a special division of infantry that formed the core of the Ottoman army. The more scholarly students became “Men of the Pen” and served in administrative posts, from which they could rise to the rank of grand vizier, the highest Ottoman official after the sultan.

The Safavid dynasty.

The main rivals of the Ottomans were the Safavids in Iran. The Safavids, originally Sufis from northwestern Iran, rose to power as the leaders of Shī`ite Turks. Under Shah Ismail I in the early 1500’s, Iran changed from a Sunni to a Shī`ite country. Through the middle of the 1600’s, the Ottomans and Safavids fought each other in a series of devastating wars. The wars ended in a costly stalemate that drained the resources of both empires. Safavid kings ruled Iran until 1722.

The Mughal Empire

of India was founded in 1526 by Babur, a central Asian prince. Using firearms, Babur’s small invasion force easily defeated much larger Indian armies. The Mughal Empire reached its peak under Akbar, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. His empire included most of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, northern and central India, and Bangladesh. Mughal society under Akbar tolerated many different religious beliefs. Akbar’s son Jahangir was a Muslim, but he had a Hindu mother. The empire officially was Sunni, but many Shī`ites held high offices. The empire grew less tolerant and declined in the 1700’s. It ended in 1858.

Colonialism

Domination by the West.

In 1798, the French general Napoleon Bonaparte invaded and conquered Egypt. The conquest shocked the Muslim world. Since the time of the Abbāsids, Muslims had viewed Europe as a barbaric land, where culture and morality remained at a low level. With Egypt’s defeat, Muslims faced a Europe that had superior military strength and openly challenged their social values. Muslims were impressed by Western military technology and were influenced by their contacts with European scientists and historians. Muslim delegations began to travel to Europe to study the latest trends in science and philosophy.

Although the French left Egypt in 1801, they returned to the Muslim world in 1830, invading Algeria. During the last half of the 1800’s and the early 1900’s, Europe either directly or indirectly controlled every Muslim country except Arabia, Turkey, and Iran. Most states of northern and western Africa became French colonies. British political influence and territorial control in India grew in the 1700’s and 1800’s. Egypt came under British control in 1882. Indonesia began to fall under the rule of the Netherlands as early as the 1600’s.

Colonialism caused drastic changes within all Muslim societies. Colonial governments introduced administrative changes and built roads, railroads, and bridges. But colonial authorities also deprived Islam of its former role in the organization of social and economic life. They reorganized the Islamic Sharī`a and supplemented it with a European system of laws. To the present day, most Muslim countries have a dual legal system. Laws governing marriage, family, inheritance, and other personal matters are usually based on the Sharī`a, while most criminal and commercial laws are based on European models.

Reform and renewal.

The most influential Muslim movement of the colonial period was the Salafiyyah (Way of the Ancestors). It was founded by Jamāl al-Din al-Afghānī, an Iranian politician and philosopher, and Muhammad Abduh, an Egyptian theologian and expert on Islamic law. The Salafiyyah attempted to reform Islam using modern Western concepts of reason and science. Afghāni also helped found Pan-Islamism, a movement that called for the unity of all Muslims. He feared that nationalism would divide the Muslim world and believed that Muslim unity was more important than ethnic identity. Muhammad Abduh’s main concerns were the reform of Islamic law and theology. He rejected the blind acceptance of the past.

The most important successors of the Salafiyyah movement were the Muslim Brotherhood, the Jamā`at-i-Islamī , and the Muhammadiyyah. An Egyptian teacher named Hasan al-Bannā founded the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928. The organization inspired Islamic reform movements in other Arab countries, including Jordan, Sudan, and Syria. The Muslim Brotherhood started as a religious and philanthropic society that promoted morality and good works. It eventually moved into politics and supported the replacement of nonreligious governments with governments based on Islamic principles. Today, the Muslim Brotherhood is one of the most influential movements in the Muslim world. It is affiliated with Islamic reform movements in non-Arab countries, such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Malaysia. It also influences Islamic centers in the United States.

The Jamā`at-i-Islamī was founded in 1941 in what is now Pakistan by Abū al-A`l’ā al-Maudūdī, who was dedicated to reviving Islam in India. After British rule ended in India in 1947, he supported the creation of an Islamic republic in Pakistan. Throughout its history, the Jamā`at-i-Islamī has supported conservative Muslim politics. The leaders have called for curtailing the influence of minority Islamic sects in Pakistan and have stirred up opposition to nonreligious governments. Although its political influence declined after the death of its founder, the Jamā`at-i-Islamī continues to attract a following among university students and the lower middle class. It also has considerable influence among Pakistani immigrants in Europe and the United States.

The Muhammadiyyah is the largest Muslim reform organization in Southeast Asia. It was founded on the Indonesian island of Java in 1912 and was heavily influenced by the views of Muhammad Abduh. The Muhammadiyyah supports a form of Islam based on reason. It has called for the social liberation of Muslim women. The Muhammadiyyah’s women’s organization is named Ā`ishah, after the Prophet’s wife. It ranks as one of the most dynamic women’s organizations in the Muslim world.

The Muslim world today

A goal held by many Muslims is the formation of a unified community of believers. But the great diversity of the modern Muslim world acts against this goal. Although most Muslims believe that “Islam is one,” there remain important differences of doctrine and practice within the Muslim world. The practice of Islam in Morocco, for example, differs in many ways from the practice of Islam in Iran or Oman. Only about 20 percent of Muslims are Arabs. The largest group of Muslims live in South Asia in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan and speak languages, such as Bengali and Urdu, that are much different from Arabic. The single nation with the largest Muslim population is Indonesia in Southeast Asia. As Islam becomes more prominent in Europe and North America, new cultural forms will add to this diversity.

Cultural differences lie behind many social controversies in Islam, especially regarding the role of women. The treatment of women varies widely throughout the Muslim world. Women in such countries as Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia live largely in seclusion and have little social or economic independence. In other countries, including Bangladesh, Malaysia, Pakistan, Turkey, and Tunisia, women are elected to parliament, serve as government officials, and may even become prime minister.

In the late 1900’s and early 2000’s, some Islamic fundamentalist groups strongly opposed countries with governments that did not follow their interpretation of Islam. Some declared that the United States was an enemy of Islam. They especially objected to U.S. support of Israel and the presence of American troops in Saudi Arabia. Some Islamic extremists called for a “holy war” against the United States and launched terrorist attacks against American citizens and property.