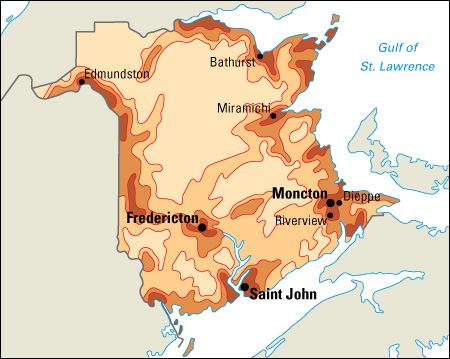

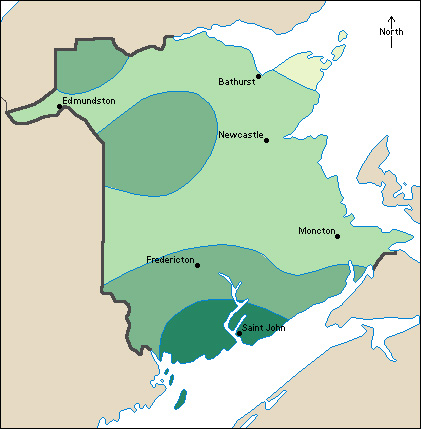

New Brunswick is one of the four Atlantic Provinces of Canada. Clear, swift rivers rush down the many hills and sweep through the steep valleys of New Brunswick. Forests cover about 85 percent of the land and add to its natural beauty. Fredericton is the capital of New Brunswick and one of its largest cities. Other large cities include Saint John, a leading industrial center and port, and Moncton, an important transportation and distribution center.

Every year, loggers cut millions of trees from New Brunswick’s thick forests. Many trees are sawed into lumber. Even more go to pulp and paper mills, where they are processed into a soft mass called pulp and made into paper.

The province has rich mineral and energy resources that give it great potential for industrial growth. Huge deposits of copper, lead, silver, and zinc lie in northeastern New Brunswick. In the 1950’s, geologists mapped the area, and in the 1960’s new facilities were built to develop the area’s resources. In the 1980’s, large potash mines opened in southern New Brunswick. A nuclear power plant began operating in 1982. The province also has the largest oil refinery in Canada, in Saint John.

New Brunswick has some moderately rich farmland in the Saint John River Valley and other regions. Potatoes rank as New Brunswick’s leading field crop. The province has one of the world’s largest frozen food industries. Beef and dairy cattle are raised throughout the province. Lobsters and crabs are the most important seafood catches. Fishing fleets on the Bay of Fundy and the Gulf of St. Lawrence make large hauls of herring and shrimp. The rivers and rolling woodlands of New Brunswick are among the best fishing and hunting grounds in North America.

In 1922, Andrew Bonar Law of New Brunswick became the only person born outside the United Kingdom or Ireland to serve as prime minister of the United Kingdom. Richard B. Bennett, another New Brunswicker, became prime minister of Canada in 1930. Other well-known New Brunswickers include Bliss Carman, one of Canada’s most famous poets; novelist David Adams Richards; and playwright and novelist Antonine Maillet.

New Brunswick was named for the British royal family of Brunswick-Luneburg (the House of Hanover). Most of its early settlers were American colonists who had remained loyal to England during the American Revolution (1775-1783). About 14,000 of these Loyalists, as they were called, arrived during and after the war, most of them in 1783. They settled among a few thousand French-speaking Acadians and several hundred Indigenous (native) people. As a result of these Loyalist settlers, New Brunswick received the nickname of the Loyalist Province. It is also called the Picture Province because of its natural beauty.

New Brunswick, along with Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec, was one of the original provinces of Canada. For the relationship of New Brunswick to the other provinces, see Canada; Canada, Government of; Canada, History of.

People

Population.

The 2021 Canadian census reported that New Brunswick had 775,610 people. The province’s population had increased by about 4 percent over the 2016 figure of 747,101.

About half the people of New Brunswick live in urban areas. About half of the people live in the metropolitan areas of Fredericton, Moncton, and Saint John. These three cities have the province’s only Census Metropolitan Areas as defined by Statistics Canada (see Metropolitan area).

Dieppe and Riverview are the only other places in New Brunswick that have a population of more than 20,000. The province has only a few other cities and towns with populations of more than 10,000.

About 95 of every 100 New Brunswickers were born in Canada. About a fourth of the others came from the United States or the United Kingdom.

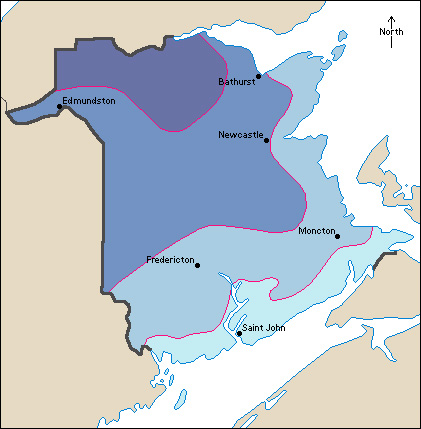

New Brunswick has two official languages, English and French. It is the only legally bilingual province in Canada. About two-thirds of the people speak English as their native language. They include descendants of the Loyalists who left the American Colonies in the 1700’s. Other English speakers include descendants of English, Irish, and Scottish immigrants who arrived in the 1800’s. About one-third of New Brunswick’s people, called Acadians, speak French as their native language. The south and west of the province are mostly English-speaking. The Acadians are concentrated in the north and east. About one-third of New Brunswickers speak both languages. About 28,000 people in New Brunswick have some Indigenous ancestry.

Schools.

During the late 1700’s, most schooling in the New Brunswick region took place in the home or in privately run schools. Most early schools were open only a few months of the year. Traveling teachers often taught the classes. An act of 1802 provided a small amount of money to help each parish (district within a county) pay for a school for younger children. However, not all parishes had schools. In 1805, an act established a grammar (high) school at Saint John. This act, along with others passed in 1816, helped to create a system of public schools by granting funds for education to each county. Parents and church groups also supported many schools in New Brunswick in the 1800’s. Since 1967, the provincial government has provided free public education for all children. New Brunswick also has privately funded Roman Catholic and other denominational schools.

District education councils consist of publicly and locally elected members. The members are responsible for establishing the direction and priorities for the school district. They are also responsible for deciding how to operate the districts and schools. Children are required to attend school from age 5 to age 18 or until they graduate. Students have the opportunity to learn in both English and French.

Libraries.

The New Brunswick Public Library Service provides library services throughout the province. The Legislative Library of New Brunswick is in Fredericton. Other libraries include the Harriet Irving Library of the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, the Ralph Pickard Bell Library of Mount Allison University in Sackville, and the Champlain Library of the Université de Moncton (University of Moncton).

Museums.

The New Brunswick Museum in Saint John is Canada’s oldest museum. It was founded as the Museum of Natural History in 1842. Today, the museum has fine cultural, historical, and scientific exhibits. The Fredericton Region Museum in Fredericton depicts the history of central New Brunswick. The Central New Brunswick Woodmen’s Museum in Boiestown has exhibits of pioneer life in the province. The Acadian Museum at the Université de Moncton features material on Acadia, a region settled by the French in the 1600’s that included what is now New Brunswick and other provinces. The Atlantic Salmon Museum in Doaktown features exhibits dealing with the Atlantic salmon and salmon fishing.

Visitor’s guide

Over a million people visit New Brunswick every year. These visitors enjoy boating and swimming off the beaches of the Northumberland Strait. In addition, the thick forests of New Brunswick offer excellent camping facilities.

New Brunswick offers some of the best fishing in North America. Fishing enthusiasts cast for fighting Atlantic salmon—the prize catch—and fish for bass, perch, smelt, and trout.

Many of New Brunswick’s most popular attractions lie along the Bay of Fundy coastline. These attractions include Fundy National Park, Reversing Falls, and Hopewell Rocks. The Bay of Fundy’s tides are among the highest in the world.

Land and climate

Land regions.

New Brunswick is in the northeastern extension of the Appalachian mountain system of the eastern United States. This area is called the Appalachian Region. Most of it consists of wooded highlands with clear, swift rivers in steep valleys. The Coastal Lowlands, also part of the Appalachian Region, make up the rest of the province.

The highlands areas of the Appalachian Region consist of the Central Highlands, the Northern Upland, and the Southern Highlands. The Central Highlands are the highest section of New Brunswick. These rugged hills increase in height from the southwest to the northeast. Many rise over 2,000 feet (610 meters) above sea level. The hills include Mount Carleton, which stands 2,690 feet (820 meters) high. It is the highest point in New Brunswick. Northwest of the highlands is the flatter Northern Upland, with an elevation of about 1,000 feet (300 meters). The Southern Highlands, along the Bay of Fundy, have long ridges and valleys. Most of the hills are less than 1,000 feet (300 meters) high.

The Coastal Lowlands of the Appalachian Region are sometimes called the Eastern Plains. They slope gently down toward the east from the Central Highlands to the shores of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Coastline.

New Brunswick has 1,410 miles (2,269 kilometers) of coastline. Deep bays and sharp inlets break the coastline in many places. The Bay of Fundy is the largest bay. Its tides are among the world’s highest. The power of the tides generally keeps the bay’s harbors free of ice in winter. But ice floes close ports on the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Other major bays include Chaleur, Chignecto, Miramichi, and Passamaquoddy.

Heavily wooded islands lie off the coast. Many of these coastal islands are summer resort areas. Numerous islands, many of which are only jagged rocks, lie in the Bay of Fundy. Grand Manan Island is the largest island in the bay. Miscou Island and Ile Lameque lie off the northeastern coast of the province.

Rivers and lakes.

The Saint John River, the longest of the province’s many rivers, flows 418 miles (673 kilometers). It rises in Maine, and drains western New Brunswick and the lower part of the Coastal Lowlands. Its many branches include the Nashwaak, Oromocto, and Tobique rivers. The St. Croix River forms part of New Brunswick’s border with Maine. The Restigouche River forms part of the border between New Brunswick and Quebec. Other major rivers include the Nepisiguit, Petitcodiac, and Southwest Miramichi.

The great tides of the Bay of Fundy rush into the Petitcodiac River and other rivers in a wall of water called a bore. This bore flows as far inland as Moncton, 20 miles (32 kilometers) away. The Moncton bore rises to about 24 inches (61 centimeters). The Bay of Fundy’s tides also produce the Reversing Falls at the mouth of the Saint John River. At low tide, the river forms a falls as it rushes to the sea through a gap between high, rocky walls. When the tide comes in, however, it overpowers the river water and creates a falls in the opposite direction. At the town of Grand Falls, the Saint John River plunges 75 feet (23 meters) over a cliff.

Grand Lake, the largest lake in New Brunswick, forms an arm of the Saint John River. Other large lakes include Magaguadavic, Oromocto, Washademoak, and the Chiputneticook chain of lakes.

Plant and animal life.

Forests cover about 85 percent of the land area of New Brunswick—a higher percentage than in any other province. Almost unbroken forest covers the central and northern areas. Most of the trees are evergreens. The principal varieties of trees in New Brunswick include balsam fir, birch, maple, pine, and spruce.

Early blue violets and pink and white mayflowers carpet the forests late in spring. In summer, blackberries, blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries are plentiful. Fiddlehead ferns flourish along riverbanks.

New Brunswick offers outstanding hunting and fishing. Forest animals include beavers, black bears, deer, moose, rabbits, skunks, and squirrels. Game birds include ducks, geese, partridges, pheasants, and woodcocks. Atlantic salmon, smallmouth bass, landlocked salmon (salmon in freshwater lakes), and trout are some of the province’s game fish. Salmon stocks had become dangerously low in the Bay of Fundy by the late 1990’s..

Climate.

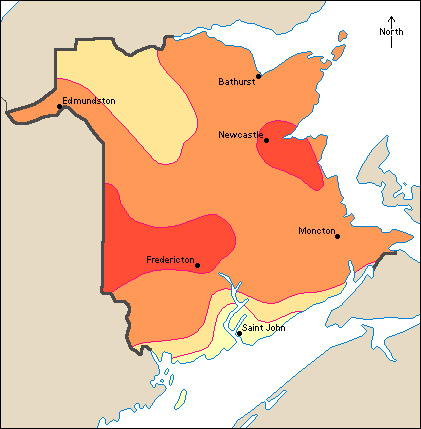

New Brunswick’s coastal regions have quick changes in temperature, but the seasonal differences are not so great as those inland. Saint John, on the coast, averages 18 °F (–8 °C) in January and 62 °F (17 °C) in July. Inland, Fredericton averages 16 °F (–9 °C) in January and 67 °F (19 °C) in July.

Northern New Brunswick’s precipitation (rain, melted snow, and other forms of moisture) averages 41 inches (105 centimeters) a year. The southern part of the province receives 47 inches (120 centimeters) a year. Snowfall in New Brunswick averages about 110 inches (280 centimeters) a year.

Economy

In the early days, the economy of the New Brunswick region was based chiefly on the timber trade and fishing. Agriculture and shipbuilding became important during the 1800’s. Today, service industries make up the largest part of New Brunswick’s gross domestic product (GDP)—the total value of all goods and services produced in a province in a year.

Natural resources.

The forests and wildlife of New Brunswick are important natural resources. Wilderness covers much of the land, and rugged terrain interfered with the early development of the province’s minerals and other resources.

The northeastern part of New Brunswick has large reserves of metallic minerals. These deposits include copper, lead, silver, and zinc. The southeastern part of the province has a major potash deposit. Bituminous coal deposits lie just north of Grand Lake. New Brunswick also has reserves of clay, gold, limestone, peat, and sand and gravel.

Soil

is not very fertile in most of New Brunswick. Farmers must use lime and fertilizers to make this soil productive. The flood plains of some rivers have a varying depth of extremely fertile black soil. Marshes and peat bogs cover parts of the east coast.

Service industries

provide the largest portion of New Brunswick’s gross domestic product and employment. Saint John and Moncton are the centers of trade and finance in New Brunswick. Fredericton, the provincial capital, is the center of government activities.

Manufacturing.

Much of New Brunswick’s manufacturing is dedicated to processing its agricultural and forest products. Leading food products include baked goods, dairy products, and fish products. McCain Foods, the world’s largest producer of French fries, is headquartered in Florenceville. Paper products and wood products are also important. Pulp and paper mills and sawmills operate throughout the province. Saint John has a large oil refinery, and refined petroleum is an important export.

Mining.

Metals provide a large portion of New Brunswick’s mining income. Zinc is the leading metal. Lead and silver also rank as leading metals. Most metal mining occurs in the Bathurst area. Peat, used primarily as fertilizer, is harvested in the northeast. New Brunswick is the leading province in peat mining.

Forestry.

Most of the trees cut down in New Brunswick are balsam firs and spruces. Other commercially important trees include aspens, beeches, birches, cedars, maples, and pines. The forestry industry has planted more than 1 billion new trees since the 1970’s.

Fishing industry.

Lobster and crab are New Brunswick’s most important catches. The province has a growing fish-farming industry, which produces oysters, salmon, and trout.

Agriculture.

Potatoes are the leading crop product in New Brunswick. Most of the potato crop comes from Carleton and Victoria counties. New Brunswick has also become an important producer of nursery products and ornamental flowers. Farmers also produce a number of fruit and vegetable crops. Dairy products rank as the leading livestock product. Much of the dairy production occurs in the southeast part of the province. Livestock farmers also raise beef cattle, hogs, and poultry.

Electric power and utilities.

A nuclear power plant at Point Lepreau, near Saint John, provides much of the electric power generated in New Brunswick. Hydroelectric plants and plants that burn coal, natural gas, or petroleum produce most of the rest of the electric power.

Transportation.

New Brunswick’s busiest airports are in Fredericton, Moncton, and Saint John. Several national and regional airlines link these cities with cities in Canada and the United States.

Railroads link the province’s major cities and are part of a network that extends to the major cities of Quebec and Ontario. New Brunswick’s major highways run along the coastal areas and extend inward to Fredericton. The Trans-Canada Highway travels along the Saint John River and through Moncton.

Saint John is one of the few seaports of eastern Canada that is free of ice all year. Transatlantic liners can dock at Saint John during the winter, even when ice shuts the ports on the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Communication.

The first newspaper in New Brunswick, The Royal Gazette and the New Brunswick Advertiser, was founded in 1785. New Brunswick’s daily papers include the Telegraph-Journal of Saint John, The Daily Gleaner of Fredericton, and the Times & Transcript of Moncton. L’Acadie Nouvelle of Caraquet is a French-language daily.

Government

Lieutenant governor

of New Brunswick represents the British monarch, Canada’s official head of state, in the province. The lieutenant governor is appointed by the governor general in council—that is, the governor general of Canada acting with the advice and consent of the Cabinet. The position of lieutenant governor is largely honorary.

Premier

of New Brunswick is the actual head of the provincial government. The province, like the other provinces and Canada itself, has a parliamentary form of government. The premier of the province is an elected member of the Legislative Assembly. The premier is usually the leader of the majority party in the Legislative Assembly.

The premier presides over the Executive Council (cabinet). The premier chooses the Executive Council from among the members of the majority party in the Legislative Assembly. Each council member, called a minister, usually directs one or more departments of the provincial government. The Executive Council, like the premier, must resign if it loses the support of a majority of the Legislative Assembly.

Legislative Assembly

of New Brunswick is a one-house legislature that makes the provincial laws. The Legislative Assembly is made up of 49 members who are elected from throughout the province. Elections for the Legislative Assembly are normally held every four years. However, the lieutenant governor, on the advice of the premier, may call for an election before the end of the four-year period.

Courts.

The highest court in New Brunswick is the Court of Appeal. It has a chief justice and five other judges. A panel of three judges hears most appeals, but some cases are argued before all six judges.

The Court of King’s Bench has a chief justice and more than 20 other judges. The court has two divisions: the Trial Division and the Family Division. The Trial Division hears civil and criminal cases. The Family Division hears cases related to family matters, including divorce.

The governor general in council appoints the judges of the Court of Appeal and the Court of King’s Bench. These judges may retire at age 65 or serve until age 75.

The Provincial Court has a chief judge and more than 20 other judges, all appointed by the provincial government. The court hears criminal matters, including cases involving juveniles. Lawyers may appeal Provincial Court verdicts to the Court of King’s Bench or, in some cases, directly to the Court of Appeal.

Local government.

The provincial government assesses and collects local taxes and administers all matters relating to education, health, welfare, and justice. City, town, and village councils handle such things as fire and police protection and maintenance of streets, sewers, and water service.

All of the cities, towns, and villages in New Brunswick have mayors and councils. Some of the cities and towns in New Brunswick also have managers.

Revenue.

New Brunswick gets about half of its general revenue (income) from taxes levied by the provincial government. Most of this revenue comes from taxes on personal income, retail sales, property, and gasoline sales. The province also receives revenue from national and provincial tax-sharing arrangements and federal assistance. Much of the other revenue comes from lottery sales and from license and permit fees.

Politics.

The major political parties in New Brunswick are the provincial Liberal and the Progressive Conservative parties. The Progressive Conservative Party was formerly named the Conservative Party, and today its members are usually called Conservatives. Other large parties include the Green Party, the New Democratic Party, and the People’s Alliance party.

History

First Nations.

The first white settlers in what is now New Brunswick found Mi’kmaq and Maliseet (Wolastoqiyik) First Nations people living in the region. First Nations are Indigenous peoples of Canada. The Mi’kmaq and Maliseet belonged to the Algonquian family, a group of Algonquian-speaking peoples. The Mi’kmaq roamed the eastern part of the region, and the Maliseet lived in the Saint John River Valley. Their name for themselves, Wolastoqiyik, comes from their name for the river, Wolastoq, meaning beautiful river.

The First Nations people liked to camp downstream from waterfalls or near the farthest reaches of tidewater in rivers. These locations provided the best fishing for salmon and trout. The First Nations people also gathered clams and oysters along the coast.

Exploration and settlement.

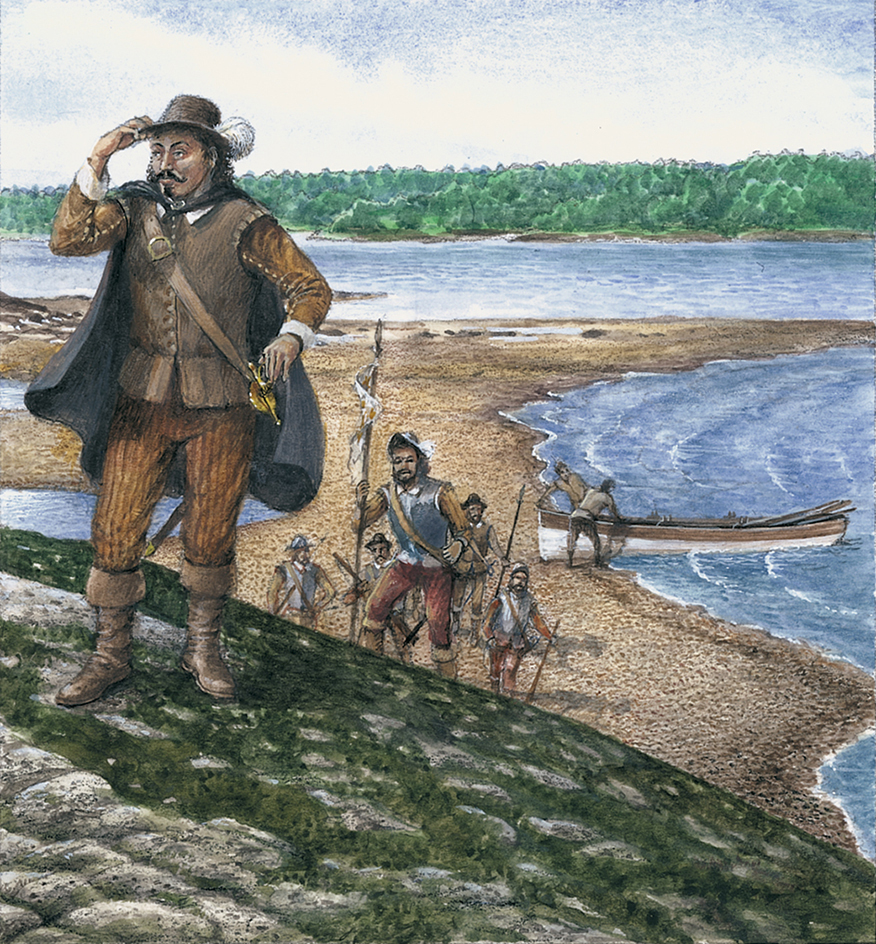

In 1534, the French explorer Jacques Cartier arrived in Chaleur Bay. He wrote of the region: “The land along the south side of it is as fine and as good land, as arable and as full of beautiful fields and meadows, as any we have ever seen. …”

No further exploration took place until 1604. That year, the French explorers Samuel de Champlain and Pierre du Gua (or du Guast), Sieur de Monts, sailed into the Bay of Fundy. After exploring the coast, they spent the winter on St. Croix Island, near the mouth of the St. Croix River. In 1605, they moved across the Bay of Fundy to Port-Royal, in what is now Nova Scotia. Later in the 1600’s, French settlers arrived and established farms and fishing stations. The French called the region Acadia (see Acadia).

French rivals.

The French, some of whom hoped to establish a fur trade, soon began to fight among themselves for control of the territory. The most famous struggle took place between Charles de la Tour and D’Aulnay de Charnisay. La Tour had a trading post and fort on the site of present-day Saint John. De Charnisay was a fur trader in Port-Royal. In 1645, after many years of rivalry, De Charnisay attacked La Tour’s fort while La Tour was absent. Marie de la Tour, the trader’s wife, led the defense of the fort but finally surrendered. De Charnisay forced her to watch him hang all members of the garrison except one, who served as executioner.

Competition among the French gradually gave way to rivalry between the French and the English. To the south, the English colonies were growing rapidly. Many English fishing crews and other people were attracted to the New Brunswick region. The English conquered Acadia in 1654, but they returned it to the French in the Treaty of Breda in 1667. The English invaded Acadia again in 1690. After Queen Anne’s War, France gave the mainland Nova Scotia area of Acadia to Britain (now the United Kingdom) in the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). But France and Britain disputed the ownership of most of New Brunswick. Many Acadians remained in the New Brunswick region. During the last of the French and Indian wars, the British captured the region. They drove out many Acadians. The Treaty of Paris (1763) confirmed British ownership of the New Brunswick region of Acadia. See French and Indian wars.

British settlement.

Traders from New England arrived in Saint John in 1762. In 1763, other New Englanders founded the settlement of Maugerville, near what is now Fredericton. That same year, the New Brunswick region became part of the British province of Nova Scotia. Many Acadians whom the British had driven from the region were allowed to return. The Acadians received grants of lands in the north and east.

During and after the American Revolutionary War, about 14,000 people loyal to Britain arrived from the United States, most of them in 1783. These Loyalists, as they were called, landed in Saint John. Most of them settled in the lower Saint John River Valley. They founded Fredericton. Others settled near Passamaquoddy Bay on the border with the United States. In 1784, Britain established New Brunswick as a separate colony. In 1785, Saint John became the first incorporated city in what is now Canada. The following year, the Colonial Legislature was created, and the farmers and landowners elected the province’s first Legislative Assembly.

Shipbuilding and the timber trade with the United Kingdom grew during the 1800’s. After 1815, thousands of English, Irish, and Scottish settlers came to New Brunswick because they could not find jobs in the United Kingdom. Some of these Irish immigrants were fleeing the Great Irish Famine of 1845-1850.

In 1825, a great forest fire blazed through about 6,000 square miles (16,000 square kilometers) in the Miramichi River region. The fire, fanned by its own hurricanelike winds, wiped out entire settlements and killed about 150 people. The homeless settlers received clothing, money, and supplies from the other provinces, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

By the 1830’s, about four-fifths of New Brunswick was still crown lands (lands held in the name of the British government). Timber traders had to pay fees to operate in the forests. In 1833, the provincial legislature began a movement to acquire the crown lands. The British government gave the lands to New Brunswick in 1837.

The Aroostook War.

Settlers from New Brunswick and Maine lived in the valley of the Aroostook River. The United Kingdom and the United States had never agreed on a boundary in this region, and disputes developed between New Brunswick and Maine loggers. The climax came in 1839 when militias from New Brunswick and Maine assembled to fight. No fighting took place, however. President Martin Van Buren of the United States sent U.S. Army General Winfield Scott to settle the dispute, which was called the Aroostook War. Scott arranged a truce. In 1842, British and American authorities established the New Brunswick-Maine boundary.

As the population of New Brunswick grew, so did demands for local autonomy. Political power shifted gradually from the British colonial office in London to the provincial legislature in Fredericton. In 1848, the United Kingdom granted New Brunswick almost complete control over its own affairs.

Confederation and progress.

In 1864, delegates from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island met in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, to discuss forming a united colony. Delegates from the Province of Canada joined them and proposed a confederation of all the British colonies of eastern North America. The delegates met again later in 1864 in Quebec. They drew up a plan for Canadian confederation that led to the creation of the Dominion of Canada. See Confederation of Canada.

Many New Brunswickers feared they would lose their political powers in the proposed union. Samuel L. Tilley, a provincial political leader, played a major part in convincing the people that the larger provinces would not control them. On July 1, 1867, New Brunswick became one of the four original provinces of the Dominion of Canada. The others were Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec. Andrew R. Wetmore, of the Confederation Party, became the first premier of New Brunswick after confederation. The most prominent premier in the years following confederation was George E. King, who passed the act establishing free public schools in 1871.

The province’s fishing, lumbering, and mining industries expanded gradually. But the increasing use of iron steamships led to the end of New Brunswick’s sailing-ship industry. It was replaced by important textile and iron industries. During the 1870’s and 1880’s, many New Brunswickers moved to western Canada and the United States. These regions offered better job opportunities.

By 1890, two national railway systems linked cities in New Brunswick with Montreal. Saint John ranked with Halifax, Nova Scotia, as a chief winter port on Canada’s east coast. However, Ontario and Quebec controlled manufacturing and trade in Canada. After 1900, the pulp industry became increasingly important in New Brunswick. Public works programs improved communication and transportation in the province during the early 1900’s. But New Brunswick’s industries suffered serious decline between 1919 and 1925. Recovery came slowly. The major growth during the 1920’s and 1930’s occurred in the paper industry.

The middle and late 1900’s.

After World War II (1939-1945), the province’s pulp and paper industries expanded greatly, and shipbuilding became important in the Saint John area. Huge deposits of copper, lead, silver, and zinc were mapped in the Bathurst-Newcastle region in 1952 and 1953. In 1953 and 1957, the province completed hydroelectric plants that provided additional power for mining and manufacturing. The largest oil refinery in Canada was constructed in Saint John in 1960.

A construction program related to the Bathurst-Newcastle metal ore deposits began in 1962 and was completed by 1968. Projects in the program included chemical and fertilizer plants, docking and shipping facilities, milling and manufacturing firms, mines, and pipelines. Mining of the metal ores began to boom in 1964, when the region’s largest mine started operations. Despite the economic stimulation provided by the construction program, New Brunswick’s standard of living remained below the national average. Migration out of the province rose.

In 1968, a hydroelectric plant opened at Mactaquac Dam on the Saint John River near Fredericton. More than half the power from this plant goes to industries in the Bathurst-Newcastle region.

During the late 1960’s, Premier Louis J. Robichaud, a Liberal, led the province in what he called a Program of Equal Opportunity. In this program, the provincial government took over the operation of all courts, schools, and health and welfare institutions. The action was taken to equalize the quality of services provided by such facilities throughout the province. The Robichaud era also was associated with a more active cultural, economic, and political role for New Brunswick’s French-speaking Acadian minority.

In 1969, the New Brunswick Legislative Assembly passed a law that made French an official language of equal status with English in the legislature itself and in courts, government offices, and schools. Later that year, the Canadian Parliament passed the Official Languages Act. This law requires federal facilities to provide service in both languages in districts where at least 10 percent of the people speak French. Under this law, the whole province of New Brunswick is considered a bilingual district for federal services.

Economic developments.

New Brunswick’s shipping facilities were expanded in the 1970’s. In 1970, North America’s first deepwater terminal for oil tankers opened near Saint John. The next year, a terminal for container ships opened at Saint John.

In the mid-1970’s, the Saint John area experienced major industrial expansion. The chief projects included the enlargement of shipbuilding and oil refining complexes. Food processing, mining, and forestry industries also expanded throughout New Brunswick.

In 1983, the first nuclear power plant in Atlantic Canada began operation at Point Lepreau. In 1983 and 1985, two large potash mines began operating in the Sussex region of southern New Brunswick. But in 1997, continued flooding caused the larger of the mines to close. Also in 1997, Confederation Bridge opened. It extends over the Northumberland Strait to connect New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. In the 1990’s, the provincial government promoted investment in information technology businesses such as telephone call centers.

An ongoing concern of provincial leaders has been how to provide jobs for the labor force, especially in the north, and to stop the emigration of young people to other parts of Canada. In 1996, the Royal Canadian Air Force base at Chatham closed. During the early 2000’s, mills that produced pulp and other wood products closed at Bathurst, Dalhousie, Miramichi, and other locations. Other mills cut production. Hundreds of people lost their jobs. The Saint John dry dock and shipyard, which had produced state-of-the-art patrol frigates for the Royal Canadian Navy, also closed.

In 2009, operations began at a liquefied natural gas receiving and regasification terminal in Saint John.