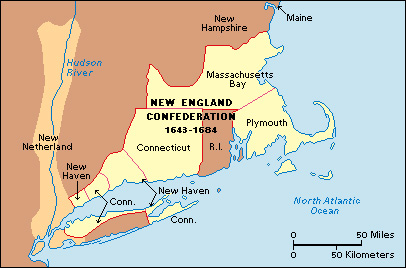

New England Confederation was organized in 1643. Four colonies—Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven—formed the United Colonies of New England, as it was called. They worked to solve boundary and commercial disputes and to meet the increased danger of attacks by the Dutch, French, and Indians. Maine, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island were excluded from membership for political and religious reasons.

The four colonies agreed to “enter into a firm and perpetual league of friendship and amity, for offence and defence, mutual advice and succor upon all just occasions, both for preserving and propagating the truth and liberties of the gospel, and for their own mutual safety and welfare.”

Two commissioners from each member colony met each year to consider problems of mutual interest. Commissioners selected a president to preside over meetings. Under confederation regulations, three colonies comprised a decisive majority. The confederation had great power in theory, but, in practice, it could only advise. A test of the confederation’s power came in 1653, when Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven favored a war against the Dutch of New Netherland. The fourth colony, Massachusetts, did not agree and absolutely refused to yield. This action lessened the prestige of the organization. After 1664, the commissioners met only every three years, and in 1684 the confederation came to an end. Despite serious weaknesses, the confederation provided valuable experience in cooperation among the colonies as well as America’s first experiment in federalism. It also helped prevent the smaller colonies from being totally dominated by Massachusetts.