New Zealand, History of. The history of New Zealand is the story of an island country in the southwest Pacific Ocean settled by two distinct peoples. The two peoples who established settlements on New Zealand were a group of Polynesians later known as Māori << MOW ree or MAH ree >> and people of European ancestry. The Polynesian ancestors of Māori traveled from the eastern Polynesian islands of the middle South Pacific, perhaps the Cook Islands or Tahiti. They probably arrived in New Zealand by A.D. 1200. British immigrants began settling in New Zealand in the early 1800’s. New Zealand became a British colony in 1840, a dominion (self-governing territory) within the British Empire in 1907, and a fully independent nation in 1947.

The history of the relationship between Māori and Europeans in New Zealand is complex. During the early period of European settlement, the two groups cooperated but also clashed and struggled over land and authority. Gradually, as European control over the land and economy increased, Europeans forced Māori into smaller and more remote regions of the country. In the 1990’s, the New Zealand government and Māori representatives negotiated several settlements. The government agreed to give land, money, and a formal apology to certain Māori iwi (tribes) to make up for past injustices.

The earliest settlers

Scholars believe that the earliest Polynesian settlers in New Zealand made a living mainly by fishing, hunting, and farming. The Polynesians brought to New Zealand several garden crops, including kumara (sweet potatoes), a root crop called taro, and yams. These newcomers had probably built settlements along the coast by A.D. 1200. Most of the early population was concentrated around the warmer, coastal areas of the North Island. Over the course of several centuries, they spread throughout New Zealand. Historians estimate that when the European explorers and traders arrived in the 1700’s, the total population was about 100,000.

In the early 1800’s, descendants of these Polynesian settlers adopted the name Māori, from their phrase tangata maori (ordinary person). Māori used the term Pākehā for the European settlers. Today, the term refers to any non-Māori New Zealanders. Māori called New Zealand Aotearoa, which is usually translated as the land of the long white cloud. Some Māori said Aotearoa was the name first used by Kupe, the legendary discoverer of the land. Although they called themselves Māori as a group, they did not see themselves as one nation. Instead, they considered themselves members of their hapu (sub-tribe) and iwi (tribe). These groups jealously defended their traditional territories, and they often warred with one another.

European exploration

Tasman and the Dutch.

The Europeans had long believed in the existence of a great land south of Asia. From the 1500’s to the 1700’s, Europeans used the name Terra Australis Incognita (Unknown Southland) for a continent they believed filled the entire southern part of the world. Several European countries sent explorers to locate and map this imagined great southern continent.

In 1642, a trading company called the Dutch East India Company sent the Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman from Batavia (now Indonesia) on a voyage of exploration. The company instructed Tasman to find and map the great southern continent, to search for new riches, and to find a sea route from Asia to South America. On Dec. 13, 1642, Tasman and his crew became the first Europeans to sight New Zealand when he saw the west coast of the South Island. Tasman then sailed northward along the coast of New Zealand and anchored in a large open bay on December 18. He made contact with some Māori who rowed out to his ships in two canoes. According to Dutch reports, Māori called out and blew a horn. The Dutch responded with shouts and trumpet blasts. Neither side understood what the other said. Historians and anthropologists believe Māori may have thought the exchange was a ritual challenge prior to battle. The next day, Māori killed four of Tasman’s men in a short battle. Tasman’s ships opened fire and moved northward, and neither Tasman nor his crew landed. This incident was a typical example of the misunderstandings that troubled early relations between Māori and Europeans.

Tasman failed to demonstrate that there was a great southern continent, leaving an incomplete chart of what he called Staten Landt. He reported that the land did not appear to be a source of any valuable trade. Tasman described the inhabitants as dangerous and therefore best left alone.

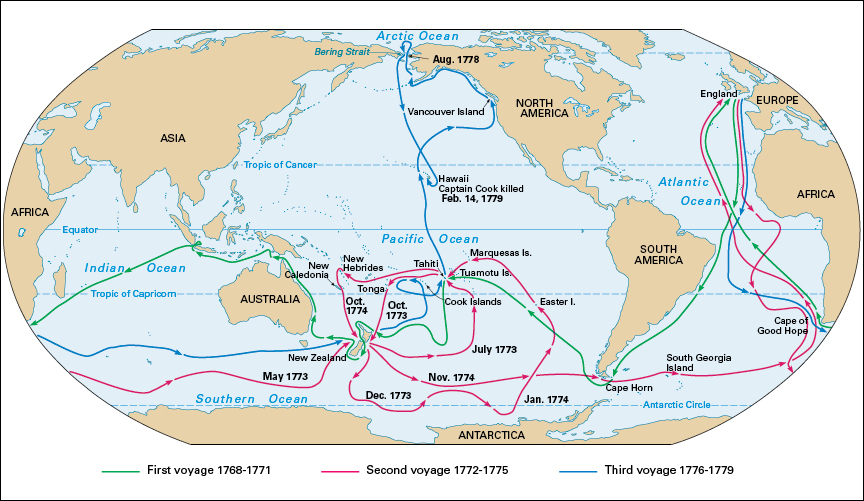

Cook’s voyages.

No European explorers visited New Zealand for 127 years after Tasman’s voyage. In 1769, the British navigator and captain James Cook came to the Pacific on his first mission of exploration and scientific discovery. Unlike Tasman, Cook made several landings on New Zealand. He treated Māori with great caution. Nevertheless, he had several violent confrontations with them, beginning with his first landing at what is now Gisborne on the coast of Poverty Bay.

Cook sailed around the North Island and then the South Island. His journey proved that New Zealand was made up of two large islands and was not part of a great southern continent. His voyage around both islands took only six and a half months and was remarkable both for its speed and for the thoroughness of its exploration. Accompanied by scientists and artists, Cook made two more voyages to New Zealand and the Pacific.

French explorers

came to New Zealand after Cook. They also had frequent conflicts with Māori groups. The French navigator Jean Francois de Surville explored the islands of eastern New Guinea and New Zealand, naming many of the islands and ports. De Surville anchored in Doubtless Bay, on the northeast side of the North Island, in December 1769, just after Cook had passed through the area. The French explorer Marion du Fresne spent five weeks at the Bay of Islands in 1772. But then he came into conflict with some local Māori, who killed him, along with 24 of his crew. The French survivors gathered their forces and counterattacked, killing about 250 Māori. The death of du Fresne shocked Europeans and warned them off New Zealand. They did not resume contact with the islands for 20 years.

Economic development

The next Europeans to visit New Zealand came mainly from the British colony of New South Wales in Australia. Some residents of New South Wales visited New Zealand to hunt seals and whales and to trade for timber products and the fibers of a plant called New Zealand flax. Others came to conduct missionary work.

The sealing and whaling industries.

In the early 1790’s, Australian settlers began seal hunting off the New Zealand coast. British, American, and other sealers soon joined the Australians. The demand for seal fur was high. But the seal population could not survive the heavy killings, and the sealing industry soon collapsed. Seal colonies were almost killed off within 20 years. But by the 1820’s and 1830’s, the seal population had recovered sufficiently to support a modest harvesting.

The whaling industry lasted much longer than the sealing industry. The earliest whalers in New Zealand waters were mostly deep-sea hunters of sperm whales. The hunters sought the whales mainly for their oil, which was used in lamps. New Zealand provided ports for the whaling ships to take on fresh food and water. In the 1820’s, some whalers began to hunt right whales along the shore. From these whales, the hunters obtained mainly oil and baleen (thin plates in the whales’ mouths through which the whales strained food). People used baleen to make many products, including corsets and umbrella ribs. The whalers began to establish communities in New Zealand. They erected buildings, planted gardens, and married Māori women. By the late 1830’s, several hundred Europeans working in the sealing and whaling industries lived along the coastline of New Zealand.

The flax and timber industries

also brought Europeans to New Zealand. In the 1790’s and early 1800’s, traders came to deal with Māori suppliers of New Zealand flax, which Europeans used for rope, and kauri timber, a valuable wood used for furniture, houses, and shipbuilding. Northern ports in such places as Hokianga Harbour developed a busy local shipbuilding industry. A growing timber trade developed with the Australian colonies. However, rising and falling demand for flax and timber caused those industries to grow and contract. The value of flax exports peaked in 1831. Exports decreased sharply after that, as people found that good-quality rope could be produced more cheaply from other materials.

Māori

played an important part in economic activities during the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Some Māori joined whaling crews or worked at shore camps. Others were involved in the supply, transport, and sale of timber. Many Māori women became the companions or wives of Europeans engaged in these trades. Māori were also eager to learn from the Europeans. Such Māori chiefs as Te Pahi of the Bay of Islands often visited Sydney, the capital of New South Wales. They brought pigs and potatoes back home, and these became valuable items of trade. In this way, Māori who traveled beyond New Zealand learned about European goods and technology.

Despite this cooperation, there was also occasional conflict between Māori and Europeans, often resulting from cultural misunderstandings. The most notable example of this occurred in 1809. A Māori who had sailed aboard the Boyd, a whaling ship, complained of ill treatment during the voyage. He prompted Māori to attack and kill most of the crew of the Boyd, while the ship was anchored in Whangaroa Harbour. But Māori wanted to develop trading relationships with Europeans. They soon realized that violence would drive the traders away and reduce profitable economic opportunities.

Conflict among Māori groups was also common. Those groups who first obtained European weapons, especially muskets, gained significant advantages over their Māori enemies. In the early 1800’s, New Zealand was the scene of bloody warfare. Hongi Hika, a powerful chief of the Ngā Puhi people, and some other northern leaders used these advantages to attack weaker communities. In a quest for mana (influence), Ngāti Toa leader Te Rauparaha led raiding parties to the South Island looking for pounamu (greenstone) and other resources.

Missionaries.

Protestant missionaries began to establish missions in New Zealand in the early 1800’s. In 1814, Samuel Marsden, an Anglican chaplain to the convicts at Sydney, established a Church Missionary Society (CMS) mission at Rangihoua in the Bay of Islands. He directed the work of several missionaries in New Zealand, including the British schoolteacher Thomas Kendall, who wrote the first grammar book for the Māori language.

The missionaries in New Zealand led a difficult life for many years. They relied heavily on support and protection from powerful Māori chiefs, such as Hongi Hika. With the arrival of the missionary Henry Williams in 1823, the CMS mission gained effective leadership. Missionaries gradually established more stations around the Bay of Islands and began to attract Māori to Christianity. In 1823, Methodists established a mission at Whangaroa. But they abandoned it after it was attacked by Māori four years later and reestablished the mission at Mangungu near Hokianga Harbour. In 1838, a French Catholic mission opened at the Hokianga Harbour under Bishop Jean Baptiste Pompallier. These missions continued to expand through the 1830’s.

The Anglicans established new mission stations, mainly along the east coast of the North Island. Methodist missionaries established their early stations mainly on the west coast. During the 1830’s and 1840’s, Māori converted to Christianity in large numbers. But some historians question whether Māori converted for practical, rather than religious, reasons. Missionaries provided access to European goods, technology, and education. By the late 1840’s, Christianity had touched almost all Māori to some extent.

The colony of New Zealand

Before 1840, no legal government had authority over the settlers and traders who came to New Zealand. Warfare between Māori groups and disputes between settlers and Māori were common. Reports of lawless conditions and fear of competition from French and American settlers led the British government to become involved in governing New Zealand. In 1835, a group of Māori leaders known as the Confederation of Chiefs of the United Tribes of New Zealand signed a declaration with the British representatives proclaiming the country’s independence. The Declaration of Independence requested that the British monarch act as the country’s protector, while recognizing Māori sovereignty (self-determination).

Edward Gibbon Wakefield.

In 1837, the British colonial reformer Edward Gibbon Wakefield formed the New Zealand Association to promote British colonization of the country. In 1839, Wakefield reorganized the association and renamed it the New Zealand Company. In August, the British government sent the naval officer William Hobson to New Zealand as its representative. The government ordered Hobson to negotiate with Māori chiefs to persuade them to give up their sovereignty. The government also authorized Hobson to serve as lieutenant governor of the British settlers in New Zealand. The British officials planned to bring New Zealand under British control and prevent the New Zealand Company from buying land. Before Hobson left England, Wakefield learned about the government’s plan and sent out his own land-buying expedition under his brother William. The New Zealand Company established settlements at Wellington and Wanganui in 1840, New Plymouth in 1841, and Nelson in 1842. The Otago Association, a settlement organization led by Free Church of Scotland elders Thomas Burns and William Cargill, established a settlement at Dunedin in 1848. In 1850, the Canterbury Association, formed by leading Anglicans in England, established a settlement at Christchurch in 1850.

The New Zealand Company’s land purchases were not entirely peaceful. In New Plymouth and Wanganui, settlers were involved in land disputes with Māori. In 1843, a party of Nelson settlers commanded by Captain Arthur Wakefield, a younger brother of Edward, clashed with Māori over land at Wairau. A total of 22 Europeans and at least 4 Māori were killed. Soon after, clashes occurred in the Hutt Valley and at Wanganui. The land disputes were resolved temporarily, and the colonists bought and settled on more land. See Wairau incident.

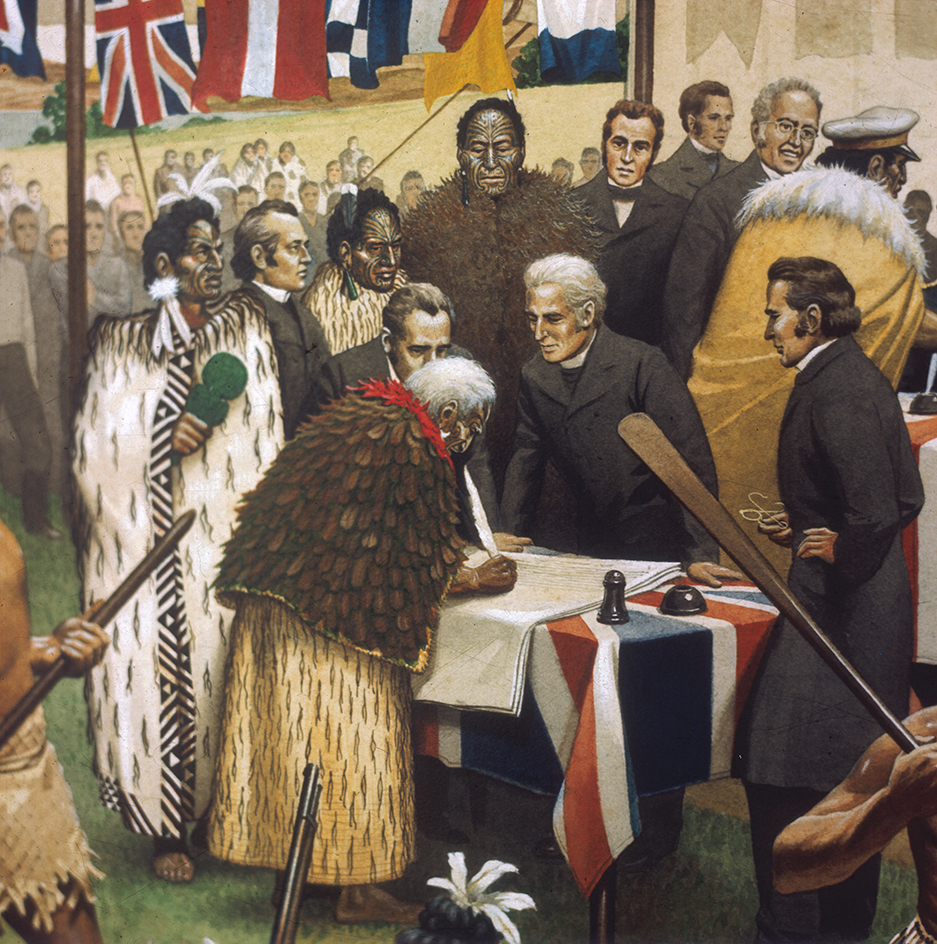

The Treaty of Waitangi.

Hobson arrived in Sydney in December 1839. There he met for several weeks with George Gipps, the governor of New South Wales, before continuing on to New Zealand. Gipps issued proclamations announcing the British decision to extend the boundaries of New South Wales to include New Zealand and to make Hobson lieutenant governor. Gipps also issued a proclamation to stop private land purchases in New Zealand. Hobson arrived in New Zealand on Jan. 29, 1840, and issued similar proclamations on the following day. He traveled to the Bay of Islands and, with the assistance of several missionaries, drafted the Treaty of Waitangi. Under its terms, Māori gave up control and authority over their lands in return for property ownership, rights as British subjects, and British protection. About 500 Māori chiefs eventually signed the treaty.

Differences between the Māori and English versions of the Treaty of Waitangi complicated efforts to reach an agreement about sovereignty. Most Māori chiefs had signed and understood the Māori-language version. Problems with the translation of some important terms led to disputes over which rights Māori kept and which they signed away. In English, the treaty called for Māori to hand over their sovereignty—that is, their right to rule themselves—in exchange for recognition of their ownership of the land and the right to be protected as British subjects. But in the Māori translation, the words used for sovereignty and ownership could be understood as giving the British limited powers to govern, rather than full sovereignty. In another controversial aspect of the treaty, Hobson extended British sovereignty over New Zealand before he had collected all the Māori signatures to the treaty. This was partly to establish his authority over all of New Zealand before the New Zealand Company settlers set up a separate government. But all Māori were included under the terms of the treaty, whether their leaders had signed it or not.

Crown colony.

Hobson began his administration in the Bay of Islands. But he soon shifted the seat of government to Auckland, where a thriving European settlement developed on the strip of land between the Waitemata and Manukau harbors. Many of the early European settlers in this region relied heavily on Māori for food and other necessities. At this time, New Zealand was still a Māori world, with European settlers concentrated in small communities.

In 1841, a charter issued by the British government separated New Zealand from New South Wales and made New Zealand a crown colony. Hobson became governor of the new colony. He established a small executive council, made up of himself and senior officials, and a legislative council, made up of the same people, in addition to at least three appointed colonists. The colonists demanded self-government, even though they were still greatly outnumbered by Māori.

Heke’s Revolt.

By the mid-1840’s, the colonists’ demand for Māori land had increased, and disputes over land ownership became more common and more violent. At the Bay of Islands, Hōne Heke, a chief of the Ngā Puhi iwi and the first chief to sign the Treaty of Waitangi, became upset with his loss of power and control to the governor. He was also disappointed that the British government was not fulfilling its promises under the Treaty of Waitangi. To protest, Heke decided to destroy the symbol of the governor’s authority by cutting down the flagpole at Kororāreka in the Bay of Islands. In 1844 and 1845, Heke and his Ngā Puhi supporters cut down the flagpole four times, and each time the British rebuilt it. Heke eventually defeated the troops who were sent to protect the town, and the inhabitants of the town fled in panic. The British colonial government brought in troops from New South Wales. Many British soldiers were killed or wounded in attacking Heke’s pā (fortified villages) at Puketutu and Ohaeawai. In early 1846, the British captured a large pā called Ruapekapeka. A short time later, Heke and the British agreed to a peace settlement.

Colonization

proceeded rapidly after the British began to exert their new authority. The New Zealand Company found the South Island particularly attractive for colonization, and British colonies soon began to prosper there. Farmers from Australia brought sheep to New Zealand. The island’s rich grasslands provided good grazing for the sheep, and the settlers began exporting wool.

Although the majority of colonists were British, settlers from other parts of Europe also came to New Zealand. These included Germans who went to Nelson, Scandinavians who settled in the Seventy-Mile Bush between Hawke Bay and the Wairarapa region, and Bohemians (from what is now the Czech Republic) who settled at Puhoi, north of Auckland. By 1851, the New Zealand Company had helped establish six settlements and had helped bring more than 15,000 colonists to New Zealand. The European population was more than 26,700. About a third of the colonists had settled in the Auckland area, about a third lived in other parts of North Island, and the rest of the colonists had established settlements on South Island.

Constitution.

In 1852, the British government granted the colony of New Zealand a constitution that recognized the scattered and diverse nature of the European settlements. The constitution called for a bicameral (two-house) General Assembly that consisted of the colonial governor (later called the governor general), a House of Representatives, and a Legislative Council. Members of the House were elected by men who met certain requirements for property ownership. Members of the Council were appointed by the governor. New Zealand also had six provincial governments—for Auckland, Canterbury, Nelson, New Plymouth (later renamed Taranaki), Otago, and Wellington—each with an elected superintendent and an elected council. The first provincial superintendents and councils were elected and met in 1853. The first General Assembly met in 1854. Because Māori owned land collectively rather than on an individual basis, they were effectively excluded from participating in this new government.

The provincial period

The New Zealand Wars (1860-1872).

As the colonists’ demand for Māori land grew, disputes over land ownership became more frequent. Government attempts to buy land often divided Māori into groups that wanted to keep the land and those who wanted to sell it. Fighting soon broke out between these groups, as well as between Māori who resisted selling and colonists who wanted land.

In north Taranaki, a feud developed over a block of land at the mouth of the Waitara River. In 1859, a minor Māori chief who led a small group that claimed to own the land told Thomas Gore Brown, the governor of New Zealand, that he would sell the Waitara block. But Wiremu Kīngi of the Te Ātiawa iwi, who was a senior chief and leader of a larger group with claims to the territory, rejected the sale. In 1860, colonial officials sent surveyors to mark the land out for settlement. Kīngi’s supporters resisted and pulled up the survey stakes. The government declared martial law (government under military rule) and sent troops to protect the surveyors. War began when government forces seized a Māori fort built on the disputed land. Other Taranaki Māori and volunteers from Waikato, a Māori-occupied region in the central North Island, joined Kīngi. This conflict, called the Taranaki War, was the beginning of the New Zealand Wars.

In 1863, the new governor of New Zealand, Sir George Grey, heard rumors that the Māori forces from the Waikato district intended to attack Auckland. Grey was also upset that Waikato Māori had established their own king and intended to halt further land sales in that part of the country. Grey ordered the invasion of the Waikato district in July 1863. He gained the support of settlers who wanted to open up the Waikato’s fertile grazing lands to British settlement. Many of these settlers also saw the Māori king as a threat to British authority in New Zealand.

Māori forces inflicted heavy casualties on the British, particularly at Rangiriri. But they were defeated at Orakau by the colonial and British forces, who outnumbered them. The British forces attacked the Māori king’s allies at Gate Pā, and the fighting spread to the Bay of Plenty. The British suffered a serious defeat there before overpowering a Māori force at Te Ranga.

There were no more official, large-scale battles in the New Zealand Wars. But small, occasional conflicts continued into the 1870’s and later in some remote regions. In 1863, a religious movement called Pai Mārire (meaning good and peaceful) and also known as Hauhau began to encourage Māori to continue their struggle to retain their land and identity. Fighting continued on the west and east coasts of the North Island.

The Hauhau fighters weakened under the sustained assault of British and colonial forces. But two outstanding Māori fighters, Riwha Tītokowaru in south Taranaki and Te Kooti in Poverty Bay, revived the Māori war effort. These leaders won several battles with the colonial forces before they were forced to retreat. Te Kooti took refuge with the Māori king in the central North Island, an area known as the King Country. Followers of the Māori king movement, or Kīngitanga, declared that they would sell no more land to Europeans and blocked Europeans from settling in the region. They eventually lifted these prohibitions during the 1880’s. Te Kooti was pardoned in 1883.

Māori suffered for their participation in the wars. Many Māori who had taken up arms against the British were labeled as rebels and punished. In 1863, the colonial government passed legislation that allowed the government to seize the land of Māori who had been declared rebels. Authorities seized about 3 million acres (1.2 million hectares) under this law. But the colonial government also rewarded some Māori who had fought for the British during the New Zealand Wars. The most significant of these rewards was the creation in 1867 of four Māori seats in the House of Representatives.In 1865, the colonial government established an agency called the Native Land Court to convert collective Māori ownership of land into individual titles. The court rejected the traditional Māori belief that land belonged to the entire tribe, not to individuals. By the end of the 1800’s, the settlers had taken most Māori land. The raupatu (seizure) of Māori land weakened the economic and social stability of many Māori communities. Many Māori were forced to withdraw into the harshest and most isolated regions of the country.

Wool and gold.

The South Island was largely unaffected by the wars of the 1860’s and developed rapidly. In the 1850’s, settlers took land in the Canterbury plains and the foothills of the Southern Alps/Kā Tiritiri o te Moana range for sheep farming. Merino wool provided the country with its first important exports. The pastoralists (livestock farmers) became a wealthy class who dominated the political and social life of the colony until their wealth was threatened by economic depression in the late 1800’s.

Farther south, the economy was also developing. In 1861, the Tasmanian prospector Gabriel Read discovered a rich field of alluvial gold (gold deposited by flowing water) in a section of Otago that was soon known as Gabriel’s Gully. Eager gold miners, mainly from the largely worked-out fields in the Australian colony of Victoria, soon flocked to the province. From Gabriel’s Gully, the diggers moved on to the rich gold-mining areas of central Otago. Otago was quickly transformed from a struggling church settlement into the most successful province in the colony. In 1864, prospectors discovered gold on the west coast of Canterbury province. Auckland prospered when gold was discovered at Thames in 1867.

Gold replaced wool as the leading export in the 1860’s. It also brought more colonists to the country than the New Zealand Company had. Most of the gold miners were men, and their largely male communities greatly altered the social structure of the population. Although the commercial and farming middle class continued to dominate New Zealand’s politics in the late 1800’s, the gold miners eventually formed the basis of a large working class.

Depression and social reform.

New refrigeration methods that were developed in the late 1800’s contributed to New Zealand’s growing prosperity. These methods made it possible to export large quantities of butter, cheese, and meat. However, the expense of supporting the New Zealand Wars, along with shrinking profits from South Island gold mines, took a severe toll on New Zealand’s young economy. Heavy government borrowing to support colonization and development projects also weakened the economy. In the late 1870’s, the country entered an economic depression that lasted until the 1890’s.

A loose grouping of liberals won election to Parliament in 1890 and formed a new government in 1891. They soon united to form the Liberal Party, which remained in power for 21 years. The Liberal Party represented the first stable, nationwide political party in New Zealand’s history. The party, under the leadership of Richard John Seddon from 1893 to 1906, carried out an extensive program of social reform. In 1893, New Zealand became the first country in the world to extend full voting rights to women.

Dominion status.

During the 1890’s, Pākehā New Zealanders, the sons and daughters of the first European settlers, began to reflect on their own national and cultural identity. They were interested in the aspects that made New Zealand different from Europe and explored this through literature, art, and nonfiction writing. Some artists, including Charles Frederick Goldie and Gottfried Lindauer, and such writers as Stephenson Percy Smith, used aspects of Māori history and traditions in their work. In 1907, the United Kingdom granted New Zealand’s request to become a dominion (self-governing country) within the British Empire.

Many New Zealanders at that time believed Māori were a dying race and would eventually be replaced by or combined with the Europeans. The Māori population reached its lowest point around 1900. But improved health and living conditions soon helped the Māori community to recover and grow.

World War I (1914-1918)

New Zealand sent about 100,000 troops to Europe to join the Allies against Germany. In 1916, the government introduced conscription (mandatory military service). Initial enthusiasm for the war soon turned to despair over the high casualty rate and enormous loss of life. About 1 in 7 soldiers from New Zealand were killed.

In one of the first actions of the war, New Zealand troops occupied German Samoa (present-day Samoa). They were then sent with troops from Australia to train in Egypt, where the term ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) was created to describe them.

On April 25, 1915, the ANZAC troops formed a vital part of the Allied forces that landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula in what is now Turkey. The campaign was part of an Allied strategy to attack the Ottoman Empire, which was allied with Germany. Allied troops hoped to take the Gallipoli Peninsula and open the way for an attack on Constantinople, the Ottoman capital. Although the British, ANZAC and other Allied forces fought with great courage, the Ottoman defense held firm. A long stalemate followed, until the Allied troops withdrew in December 1915 and January 1916. New Zealand lost more than 2,700 soldiers in the campaign. Although the Gallipoli campaign was a military failure, it established the fighting reputation of the ANZAC soldiers. It has remained one of the most important events in the history of New Zealand.

Later in the war, New Zealand troops were sent to France , where they were involved in heavy fighting. The New Zealand forces also included the Māori Pioneer Battalion. Māori made a significant contribution to the war, fighting both at Gallipoli and in France.

The Great Depression

Important technological advances became widely available in New Zealand after World War I, including the automobile and the milling machine for working metal. Electric power rapidly expanded through the construction of hydroelectric programs. New Zealanders prospered in a postwar economic boom until 1921, when world prices for the country’s exports dropped.

In 1929, New Zealand’s economy declined sharply as the country entered the Great Depression, a worldwide economic downturn. By late 1933, the New Zealand government estimated that more than 80,000 people, approximately 12 percent of the work force, were unemployed. However, official statistics did not include most women and Māori, so the actual unemployment rate was probably much higher. In the major cities, joblessness and desperate living conditions led to rioting. In an attempt to address these problems, the government put unemployed men to work on useful public projects. The men lived in public works camps and worked for minimum wages on road construction, forest planting, and swamp draining.

In the 1935 general election, the Labour Party came to office. The new government had a broad vision of social and economic reform based on socialist principles. It increased public works projects, such as railroad and road construction and forest planting, and raised relief wages. In 1938, the government introduced a social security program that included health care for all citizens and special benefits for the elderly, children, and widows.

World War II (1939-1945)

When the United Kingdom entered World War II against Germany in September 1939, New Zealand declared war as well. The New Zealand war effort was chiefly concentrated in the Middle East and Europe. As in World War I, New Zealand introduced conscription to maximize the war effort.

New Zealand pilots fought with distinction in the Battle of Britain, an air conflict over southern England between the Luftwaffe (German air force) and the Royal Air Force, from July to September 1940. New Zealand troops fought in Egypt and then Greece, where they suffered heavy casualties in an unsuccessful attempt to resist the German advance. The Allied troops were evacuated to Crete, where they fought a massive German airborne attack. Many of the Allied troops were evacuated and regrouped in Egypt, where, at El Alamein, they eventually defeated German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrikakorps. The New Zealanders, including a new Māori Battalion, formed a vital segment in Sir Bernard Montgomery’s British Eighth Army. That army swept across North Africa and fought its way up the Italian peninsula.

When Japan entered the war in 1941, New Zealanders began to fear a Japanese invasion of their country. As British power declined in the Pacific, New Zealand increasingly relied on the United States. Forces from New Zealand fought beside those of the United States in the Pacific Islands. Between 1942 and 1944, many thousands of American servicemen were stationed in New Zealand or stopped at New Zealand ports on ships heading to or from combat in the Pacific. Their presence helped popularize American ideas and culture in New Zealand.

The war changed life on the home front. The government introduced rationing (controlled distribution) of gasoline, clothing, and some items of food. But other hardships eased. During the war, New Zealand’s domestic economy boomed. Manufacturing and farm production rose, and wages and prices stabilized. Unemployment virtually disappeared when many men went to war and women replaced them on farms and in factories. During the war, women experienced a new kind of independence through working in jobs that had previously been done by men. This was a temporary freedom, however, because returning soldiers resumed their duties.

Postwar New Zealand

The postwar period was a time of great social change for many New Zealanders. Postwar prosperity led to a period of economic stability. The government provided some housing and employment, and the overall standard of living improved. After the war, many Māori migrated from the rural areas, where they had traditionally lived, into urban areas. City life offered new economic and educational opportunities for Māori. But it also resulted in isolation from their traditional lifestyle. Many newcomers to city life felt increasingly dislocated from their land and culture.

Māori-Pākehā relations.

Since the 1840’s, Māori had protested government violations and abuses of the Treaty of Waitangi. In 1975, Māori showed their anger with a march from the far north of the North Island to the capital city of Wellington . That same year, the New Zealand government established a commission of inquiry called the Waitangi Tribunal to investigate Māori claims of British violations of the treaty. The tribunal consists of an equal number of Māori and Pākehā members, appointed by the governor general. In addition to investigating claims, the tribunal suggests possible settlements. At the time of its creation, the Waitangi Tribunal could only hear claims that arose from laws passed or actions taken after the law that created the tribunal went into effect in 1975. But in 1985, the government amended the tribunal’s power and allowed it to consider historical claims dating back to 1840.

In 1995, the New Zealand government negotiated a settlement with Tainui Māori that called for financial payments and the return of land. The settlement also included a formal apology for historical injustices, including the seizure of Māori land. Since then, the government has made settlements with several other Māori iwi, including Ngāi Tahu in the South Island, and some Taranaki iwi from the west coast of the North Island.

International tensions

developed between New Zealand and some of its overseas allies during the 1980’s. In 1981, a tour by a South African rugby team sparked an international controversy when thousands of New Zealanders protested South Africa’s policy of apartheid (racial segregation). In 1984, Labour Party Prime Minister David Lange announced that New Zealand would ban ships carrying nuclear weapons or powered by nuclear reactors from entering its ports. This ban brought New Zealand into disagreement with the United States, a military ally. In 1986, the United States suspended its military duties to New Zealand under the ANZUS mutual defense treaty. The ANZUS treaty had been signed by Australia, New Zealand, and the United States in 1951. This suspension was partially lifted in 1999 to allow troops from the United States and New Zealand to participate in joint United Nations (UN) peacekeeping operations.

New Zealand also strongly opposed France’s testing of nuclear weapons in the South Pacific. In 1985, the environmental organization Greenpeace planned to use its ship, the Rainbow Warrior, to protest French nuclear tests in the Pacific. But French secret agents bombed and sank the ship in Auckland Harbour. France apologized for sinking the ship in New Zealand waters but prevented the secret agents from serving out their prison terms in New Zealand. Since then, New Zealand has continued to maintain its antinuclear position. In 1996, New Zealand cosponsored a UN resolution to ban nuclear weapons from the Southern Hemisphere.

Economic uncertainty.

The 1970’s and 1980’s were years of great economic change in New Zealand. In 1984, the government began several important economic reforms to decrease its regulation of certain areas of the economy and establish a free-market economy. Government officials lowered trade tariffs (taxes on imported goods) and reorganized many government agencies or sold them to private owners. The government also imposed a goods and services tax, increasing the cost of almost every consumer purchase.

By 1990, these economic reforms had achieved only limited success in boosting the national or regional economies. New Zealanders voted the Labour Party out of office in the general election of 1990, replacing it with a National Party government.

Electoral changes.

The 1990’s brought major political changes to New Zealand. Until the early 1990’s, New Zealand had a first-past-the-post electoral system, in which each parliamentary representative was the person who had received the most votes in his or her electoral district. In late 1992, a national referendum (bill sent for public vote) asked voters to choose between retaining the existing first-past-the-post system and modifying the electoral system. Over 85 percent voted to change the system. In 1993, New Zealand adopted a mixed member proportional (MMP) system of electing members of Parliament. In this system, some seats are reserved for elected legislators, while others are divided among the parties that receive 5 percent or more of the popular vote according to their share of the total votes cast. See Preferential voting .

In the 1996 election, the first held under the new MMP system, none of New Zealand’s political parties won an outright majority. The number of seats held by third parties and Māori increased dramatically. To obtain a majority, the traditionally conservative National Party formed a coalition with the New Zealand First Party. The election showed that, under the new system, coalitions were the most likely outcome and that political parties would therefore have to work together to accomplish their goals.

Recent developments.

In 1997, Jenny Shipley replaced Jim Bolger as the leader of the National Party and prime minister. Shipley was New Zealand’s first woman prime minister. In the general election of 1999, a coalition of the Labour and Alliance parties won a majority of seats in Parliament. Helen Clark, the Labour Party’s leader, became the first elected woman prime minister in New Zealand. In elections held in 2002, a coalition of the Labour and Progressive Coalition parties won the most seats in Parliament. Clark remained as prime minister. In a September 2005 election, Labour won more votes than any other party, and Clark remained in office as prime minister. The National Party defeated Labour in parliamentary elections in late 2008, and National Party leader John Key replaced Clark as prime minister. Key and the National Party remained in power after elections in 2011 and 2014.

In September 2010, an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.1 struck Christchurch, causing widespread damage but no direct fatalities. (Magnitude is a measurement of an earthquake’s strength based on ground motion.) Thousands of aftershocks affected the region in the months following the quake. In February 2011, a 6.3-magnitude earthquake shook the city, causing additional damage and killing more than 180 people. Additional aftershocks followed. In November 2016, a 7.8-magnitude quake caused widespread damage in the northeastern region of the South Island.

In December 2016, John Key stepped down as National Party leader and prime minister. The National Party selected Bill English to succeed Key in those roles. In a September 2017 general election, no party won a majority of seats in Parliament. Labour, the Greens, and New Zealand First formed a governing partnership, and Labour leader Jacinda Ardern became prime minister in October.

In March 2019, a white supremacist gunman attacked two Christchurch mosques (see Christchurch mosque shootings of 2019). The shooter, who broadcast the assault live over the internet, killed 51 people and injured dozens more before being detained by police. It was the deadliest terrorist attack in New Zealand’s history. Ardern’s government soon introduced new laws banning the ownership of most automatic and semiautomatic weapons. The legislation overwhelmingly passed through Parliament and became law. In March 2020, the gunman pleaded guilty to 51 murder charges, as well as 40 charges of attempted murder and 1 charge of terrorism. Later that year, he was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole, the maximum penalty under New Zealand law.

Beginning in 2020, New Zealand faced a public health crisis as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (global epidemic). COVID-19 is a sometimes-fatal respiratory disease that originated in China in late 2019. New Zealand recorded its first case in late February 2020. The government quickly restricted travel to New Zealand from other countries. In late March, the government announced the closing of schools, nonessential businesses, and public places and told residents to stay at home. It also began establishing programs to provide financial assistance for workers and businesses. By early June, the government had eased most internal restrictions following a remarkable decrease in new cases of COVID-19, but it retained tight restrictions for people entering the country from overseas.

In October 2020 parliamentary elections, Labour won a rare outright majority of seats, and Ardern remained prime minister. Observers credited voters’ strong support for the Labour Party to Ardern’s handling of both the 2019 terrorist attack and the COVID-19 pandemic.

New Zealand’s strict COVID-19 policies kept case numbers low until COVID-19 vaccines became available. The nation’s vaccination program began in early 2021. By early 2022, more than 80 percent of all eligible New Zealanders who were 5 years old or older were fully vaccinated. The government eased many restrictions and shifted its goal to containing, rather than eliminating, the spread of a new, more contagious variant of the virus that causes COVID-19. Beginning in early 2022, New Zealand experienced a significant increase in the number of COVID-19 cases. By early 2023, more than 2.2 million cases had been recorded in New Zealand, and more than 2,500 New Zealanders had died from the disease.

Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom died on Sept. 8, 2022, at Balmoral Castle, in Scotland. She had reigned for more than 70 years. As the British monarch, the queen also served as the official head of state of New Zealand, represented in New Zealand by the governor general. Elizabeth’s eldest child, Charles, succeeded her. He became King Charles III of the United Kingdom, and the official head of state of New Zealand.

In January 2023, Ardern unexpectedly announced her resignation as prime minister and Labour Party leader. She was succeeded in both roles by Chris Hipkins, a Labour Party minister and leader of the House of Representatives. Hipkins was sworn in as prime minister later in January.

In parliamentary elections in October 2023, the National Party won more seats in the House than any other party. The National Party, New Zealand First, and ACT New Zealand then formed a coalition government. Christopher Luxon, leader of the National Party, became prime minister in November.