Norman Conquest is the name given to the conquest of England in 1066 by William, Duke of Normandy. The duke, who was also known as William the Conqueror, led a Norman army across the Channel into England (see Normans).

William was a proud and ruthless ruler and a vassal of the king of France. He hoped to follow his distant cousin, King Edward the Confessor, as king of England. William claimed that Edward had named him as his successor. The chief English contender for the throne was Harold, Earl of Wessex. But William also claimed that Harold, who had visited Normandy in 1064, had sworn a solemn oath to support William’s claim to the throne. In 1066, King Edward died. The Anglo-Saxon witenagemot (great council) chose Harold as king (see Harold II).

William at once declared his right to the throne. He claimed to have the support of the pope and gathered an army from northern France. William landed in England without opposition at Pevensey, between Eastbourne and Hastings.

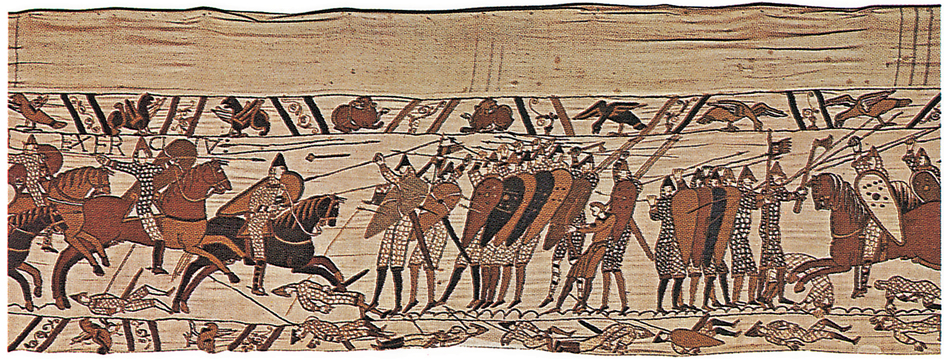

The Normans were aided in their successful landing by a chance happening. While Harold was waiting for the Normans to arrive, he received news that a Norwegian force had landed in the north of England. He hastened north and defeated the Norwegians. Meanwhile, William landed his force on the unprotected coast. Harold then marched back across England. But as he approached Hastings, he was attacked by William on Oct. 14, 1066. This was the historic Battle of Hastings, which established the Norman rule of England. Harold was defeated and slain. William marched on to London and was crowned king of England on Christmas Day, 1066. At first, he tried to win over the English nobles. But they opposed him stubbornly, and he spent several years subduing them.

William established Norman rule in England on a strong foundation. He hesitated at no act which he thought would increase the power of the crown. William took almost all the land of the English nobility, keeping some for himself and dividing most of the rest among his Norman followers. William forced all landholders to swear loyalty to himself. In this way, he put all the lords of England under his direct control. In order to know conditions in England, he directed the preparation of the famous Domesday Book, a survey of all the regions in his kingdom (see Domesday Book).

The descendants of the Normans became the ruling class in England. For a time, they kept themselves aloof from the Anglo-Saxons and treated them as a conquered people. But as the years went by, the Normans and the Anglo-Saxons intermarried. The two peoples, which even in the beginning were similar, blended into one. Today, many English families claim—though few can prove—descent from the Norman conquerors.

The Normans contributed much to the English language and to English literature and architecture. At first, the Normans spoke French. Later, the Norman French blended with Old English, the Germanic tongue of the Anglo-Saxons. This blending produced Middle English, which eventually evolved into Modern English.

See also England (The Norman Conquest); Hastings, Battle of; Ireland, History of (The Normans in Ireland (1100’s-1400’s)); William I, the Conqueror.