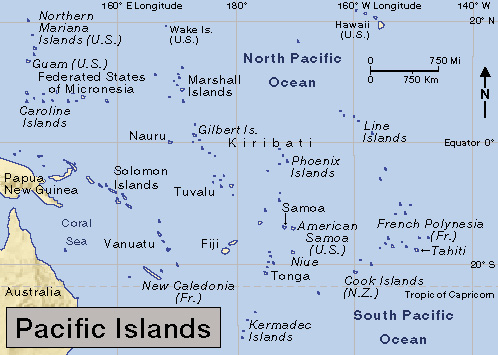

Pacific Islands are thousands of islands scattered across the Pacific Ocean. Geographers estimate that there are from 20,000 to more than 30,000 islands in the region. Some islands cover thousands of square miles or square kilometers. Others are no more than tiny piles of rock or sand that barely rise above the water.

Most of the Pacific Islands are part of a region called Oceania. This region includes numerous small islands, as well as New Guinea and New Zealand. New Guinea is the largest island in the group and the second largest in the world, after Greenland. New Zealand’s North Island and South Island are the second and third largest islands in Oceania. New Guinea and New Zealand together make up more than four-fifths of the total land area of the Pacific Islands.

Some people consider Australia a part of Oceania. However, some geographers consider it a continent and therefore not part of the region. Islands near the mainland of Asia—such as those that make up the nations of Indonesia, Japan, and the Philippines—are part of Asia, not Oceania. Similarly, islands near North America and South America—such as the Aleutians and the Galapagos—are grouped with those continents. These outlying areas are part of what is called the Pacific Rim.

The Pacific Islands are often divided into three main areas: (1) Melanesia, to the southwest; (2) Micronesia, to the northwest; and (3) Polynesia, to the east. The land and climate differ greatly throughout Oceania. Many of the islands are famous for their white beaches and swaying palm trees. Other islands have thick jungles and tall mountain peaks. Many lowland areas in these islands are steaming hot, but the tallest mountain peaks are covered with snow throughout the year.

About 22 million people live in the Pacific Islands. The largest populations are on New Guinea and on the islands that make up Fiji, Hawaii, and New Zealand. In most Pacific Island countries, many people speak or understand English. French Polynesia and New Caledonia are in the French-speaking Pacific.

The first Pacific Islanders came from Southeast Asia several thousand years ago. Over many centuries, they settled most of the islands of the Pacific and developed a variety of complex cultures.

Europeans first arrived in the Pacific in the 1500’s. The Pacific Islands were part of the “South Sea,” as described by the Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1513. The Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan called the ocean the Pacific—meaning peaceful—after he emerged into the calm ocean following a turbulent passage through the strait south of South America. The name Oceania came into use during the early 1800’s.

Europeans dramatically affected Pacific Island societies and cultures. Europeans brought capitalism, Christianity, and new ideas about land ownership. They also brought diseases that devastated many island communities. Most parts of the Pacific Islands did not encounter Europeans until the 1700’s. By the late 1800’s, several European nations, as well as Japan and the United States, had taken control of much of Oceania. These colonizing nations brought their own ways of life to the islands.

In the early 1960’s, many islanders began to demand the freedom to govern themselves. The demands led to the process of decolonization, in which most islands or island groups became independent or gained some form of self-government.

Today, France maintains its territories of French Polynesia, New Caledonia, and Wallis and Futuna. The United States administers American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas, and Guam. Hawaii is the 50th state of the United States. Easter Island (also known as Rapanui) belongs to Chile. Indonesia controls Papua (formerly Irian Jaya) on the western half of the island of New Guinea.

People

The Pacific Islands feature a diverse group of cultures and communities. Experts believe the first settlers in the Pacific Islands voyaged from Southeast Asia, southern China, and Taiwan thousands of years ago. These early settlers covered thousands of miles by means of rafts and voyaging canoes and followed land bridges whenever possible.

Over many centuries, most of the islands of the Pacific became settled, and a variety of complex cultures emerged. This variety reflected differences in geography and environment, social organization, and the resources the early settlers brought. The lifestyles of most inhabitants of the large islands emphasized sophisticated farming techniques. People on smaller islands developed complex fishing and gathering skills. Such skills as canoe building, mat weaving, and tool crafting led to extensive trade networks.

Peoples of the Pacific Islands.

When European explorers visited the Pacific Islands, they noted that the island communities had different languages, religions, and customs from one another. In 1831, the French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville proposed the division of the Pacific Islands into Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. He based the divisions on the geography of the islands and on how he viewed the culture and ethnic background of the Indigenous (native) peoples.

Pacific Island population groups are not clearly divided among these geographic and cultural areas. Over the years, people from each of the areas have migrated to the other areas. In addition, Pacific peoples often move between their home islands and other communities in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

Some scientists suggest only two basic island divisions—Near Oceania, including the earliest settled islands of Melanesia; and Far Oceania, including some southeastern islands of Melanesia and all of Micronesia and Polynesia. Others classify the islands according to d’Urville’s three divisions. Many islanders themselves use the three divisions to describe their own political, cultural, and artistic identities.

Melanesians

inhabit the islands of the southwestern Pacific. The name Melanesia comes from Greek words meaning black islands. Early visitors to the region gave it this name because of the dark skin of its inhabitants. Melanesia today includes the independent countries of Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu, as well as the French territory of New Caledonia. The country of Fiji is also included in Melanesia, even though it shares many cultural characteristics with Polynesia. Most Melanesian islands lie south of the equator.

Although the term Melanesia is based on a racial classification now abandoned by anthropologists, many modern islanders embrace it. Anthropologists describe typical Melanesian societies as big man systems. In these systems, men are essentially equal. Informal leaders, called big men, gain influence, wealth, and status by virtue of their speaking skills and powerful personalities.

Micronesians

inhabit the islands of the central and northwestern Pacific. The name Micronesia comes from Greek words meaning tiny islands. These islands lie north of Melanesia, and most of them also lie north of the equator. More than 2,000 islands, mostly low-lying coral islands, make up Micronesia. Micronesia includes Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas, the Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, and the Republics of Kiribati and of the Marshall Islands. The islands of Micronesia are politically divided between those that had colonial relations with the United States and those, now within the countries of Kiribati and Nauru, that did not.

Micronesia has a wide variety of cultures and languages. The region contains both hierarchical societies, in which certain people are more powerful than others, and egalitarian societies, in which people are essentially equal.

Polynesians

are the peoples of the eastern Pacific. Polynesia comes from Greek words meaning many islands. Polynesia occupies the largest area in the South Pacific, stretching from Midway Island in the north to New Zealand, 5,000 miles (8,000 kilometers) to the south. The easternmost island in Polynesia, Easter Island, lies more than 4,000 miles (6,400 kilometers) east of New Zealand. American Samoa, the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, Hawaii, New Zealand, Niue, Samoa, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Wallis and Futuna are in Polynesia.

The Polynesian islands are the most recently settled area of all Oceania. Many Polynesian groups—including those of Hawaii and Tahiti, as well as New Zealand’s Māori—can trace their genealogical connections to each other.

Scientists believe that the first Polynesians were seafaring peoples who began their journey from Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga. They possessed advanced knowledge of navigation, a skill that enabled them to cross the great distances between the islands.

Polynesian societies are mostly hierarchical. Some cultures are based on chiefdoms, and others on kingdoms. Both men and women can become chiefs, but in the traditional system men normally act as talking chiefs (spokespeople) for female leaders.

Other peoples.

The Pacific is home to many migrant groups. In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, for instance, people from a number of countries, including China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Portugal, and Puerto Rico came to Hawaii to work on plantations.

Today, Chinese communities can be found throughout much of Polynesia. Americans, Chinese, Europeans, Filipinos, and Japanese live in the islands of Micronesia. Much of Melanesia is home to people of Asian and European heritage. Large French populations exist in French Polynesia and New Caledonia. Most New Zealanders have British ancestors. Nearly half of Fiji’s population is descended from laborers imported from India in the late 1800’s.

Languages.

The Pacific Islands are home to about 20 percent of the world’s languages. Melanesia has the region’s greatest diversity of language. About 850 languages are spoken in Papua New Guinea alone. More than 100 languages are spoken in Vanuatu and in the Solomon Islands. About 15 languages are spoken in Micronesia, and about 30 in Polynesia.

In addition to native languages, many Pacific Islanders speak Chinese, English, French, Hindi, or Japanese. This diversity of languages reflects the region’s colonial past. English is the dominant language in the north and south. French is widely spoken in French Polynesia, New Caledonia, and Wallis and Futuna. Spanish is spoken on Easter Island.

Several Pacific societies—including Fiji, Hawaii, French Polynesia, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu—have developed simplified, mixed languages called pidgin languages. These languages give people who speak many languages a means of communicating with one another.

Religions.

Before the arrival of Europeans, the islands had a number of religions, all based on a belief in numerous gods or spirits. Most religions had a complex mythology centered around stories of the creation of Earth and relationships between the gods and people. See Mythology (Mythology of the Pacific Islands).

Christianity has been the most widely followed religion in Oceania since the late 1800’s. Asian populations in the Pacific are primarily Buddhist or Christian. Most of Fiji’s Indian population is Hindu, and others are Christian, Muslim, and Sikh. The Bahá’í Faith has also gained converts in the islands.

Traditional beliefs and practices involving music, dance, eating and exchanging food, and other ceremonies still exist, especially in Melanesia. In other islands, these practices are often mixed with Christianity. Almost all islanders honor their ancestors in various ways.

Ways of life

Many Pacific Islanders live in the same kinds of houses, eat the same kinds of food, and wear the same kinds of clothing their ancestors did. Most Pacific people have codes of conduct and behavior rooted in traditional custom. Some of these include the fa’a Samoa (Samoan way) and te katei ni Kiribati (Kiribati custom). These codes of conduct include family and community values and behavior, as well as rules for land ownership. Although in the past men typically dominated political and economic life, today many women have become community and national leaders.

Villages.

Most Pacific Islanders live in small farming or fishing villages. These communities consist of families who have been connected for hundreds of years. As a result, village residents know one another and feel close kinship. Villages have varying degrees of access to towns, cities, and transportation hubs. Access is most difficult in the highlands of Papua New Guinea and other remote areas.

Towns and cities

in the Pacific developed around colonial and missionary settlements or military stations. Most towns are small. New Zealand has several large cities, including Auckland and Christchurch. Other cities include Honolulu, Hawaii; Noumea, New Caledonia; Papeete, French Polynesia; Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; and Suva, Fiji.

Food

is central to Pacific cultures and is the primary way in which cultural groups connect. Extended families in Polynesia and Kiribati are described as kainga or aiga, which means those who ate together.

Traditional Pacific Islands crops include Polynesian arrowroot; bananas; the fruit of breadfruit and pandanus trees; sago palm; taro, a plant with a starchy underground stem; and yams. The most important resource for islanders living on or near coasts has traditionally been the coconut palm tree. The tree provides sweet-tasting coconut meat; sap that can be used to make drinks, sugar, and vinegar; and a range of materials for clothing and construction. Another traditional crop, the sweet potato, is native to South America. Scientists do not know when or how Polynesian people first acquired the plant, but believe that Polynesian voyagers probably carried it from Easter Island back to islands farther east in about the 1200’s to the 1300’s. Centuries later, Europeans brought additional plants to the Pacific from South America and the Caribbean. These crops included the cassava, pineapple, and another form of taro.

Islanders traditionally ate much fish and other seafood. Pork was a food reserved for feasts. Today, islanders also eat beef, chicken, and other meats. In many islands, these foods are cooked in earth ovens, shallow pits lined with heated stones. Cooks place the food on the stones and cover it with a layer of leaves. The pit is then filled with earth to hold in the heat.

The kava plant is used to create a fermented ceremonial and recreational drink called kava, ava, or kavakava. Melanesians and Micronesians consume the betel nut (seed of the palm tree). When chewed together with the leaf of the betel vine, the mixture acts as a stimulant—that is, it increases the activity of the nervous system. See Betel.

Clothing.

Many people in the Pacific Islands, especially in the towns and cities, wear clothing like that worn in Europe and the Americas. Women throughout the Pacific Islands, as well as men in Micronesia and Polynesia, generally dress modestly except during certain rituals and dances.

Some forms of traditional dress are still worn. In Fiji, Kiribati, and Polynesia, men and women sometimes wear a cloth skirt called a lava-lava or sulu. Some women wear long, loose-fitting cotton garments that are called tibuta blouses in Kiribati and meri blouses in Papua New Guinea. Muumuus, also called Mother Hubbard dresses, are still worn in such places as the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, Hawaii, and Vanuatu. Colorful shirts, called aloha shirts in Hawaii and bula shirts in Fiji, are worn mainly by men. In the Federated States of Micronesia, some women wear elaborately decorated handmade skirts. In Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga, men and women wear skirts made of tapa cloth for formal occasions and performances. Islanders make tapa cloth by stripping the inner bark from paper mulberry trees, soaking it, and then beating it with wooden clubs. In Kiribati, dancers wear skirts made of coconut fiber and woven pandanus leaves.

Arts.

Pacific Islanders practice a wide range of artistic traditions. These include carving, dance, drawing, music, painting, pottery, sculpture, weaving, and the construction of canoes, masks, and wigs. Art is not always a separate practice for islanders. Most art was made to be used as part of everyday life. Music and dance are not just for entertainment, but also for recording and marking key events and relationships. For Pacific Islanders, the performance arts are a means of preserving and passing on history and genealogy. See Sculpture (Pacific Islands sculpture).

Festivals occur regularly in Oceania. In the Festival of Pacific Arts, hosted every four years by a different island country, artists of all kinds gather to display their talents and celebrate the many Pacific cultures.

Recreation.

In every Pacific society, people gather for feasts that center on births, birthdays, weddings, funerals, and the construction of important buildings such as churches and schools. Music and dance are central to these gatherings.

Sports are another important part of Pacific Island life. Islanders practiced native forms of boxing, canoe racing, surfing, and wrestling before the arrival of Europeans. Basketball, cricket, netball, rugby, soccer, and volleyball are played throughout the South Pacific. Since the 1970’s, canoe racing has become especially popular. Every four years, Pacific Island countries gather to compete against each other in the South Pacific Games.

Education.

All Pacific Island countries have primary and secondary schools. However, many island children do not continue their education beyond elementary school. Relatively few young people finish high school and go on to colleges or universities. Literacy rates vary throughout the region, but are often high. Christian missionaries started many of the first schools, and religious institutions continue to support education. Fiji, Hawaii, Papua New Guinea, and New Zealand have large universities. Smaller universities and colleges exist in a number of locations, including Vanuatu, Guam, and Samoa.

The land and climate

The islands of the Pacific are usually divided into two main types: (1) high islands and (2) low islands.

The high islands

feature a range of ecological areas, ranging from beaches and coastal flats to valleys and rugged mountains. This variety provides a great diversity of plants and wildlife. Many islands are active volcanoes. The “Ring of Fire,” a zone of frequent earthquakes and volcanoes, surrounds the Pacific region.

The largest islands of the Pacific—New Britain, New Caledonia, New Guinea, and the North Island and South Island of New Zealand—are high islands. The high islands also include the main islands of such groups as Fiji, Hawaii, the Marianas, the Samoa Islands, the Solomons, and Vanuatu.

The low islands

often consist of coral reefs, which are formed by the skeletons of millions of tiny sea animals called coral. Thousands of these islands are scattered throughout the Pacific. Most of them are smaller than the high islands and rise only a few feet or a meter above sea level.

Many of these islands are atolls. An atoll is a coral reef—or a number of small reefs called motus—surrounding a large lagoon. Most atolls rise no more than 16 feet (5 meters) above sea level, and some lie off the coasts of high islands. Examples of coral atolls include the islands of Kiribati, Tokelau, Tuvalu, the Marshall Islands, and the Tuamotus in French Polynesia. Movements of Earth’s crust have lifted some atolls higher than others. Such raised atolls include Banaba in Kiribati, Nauru, and Niue.

Climate.

Almost all the islands of the Pacific lie in the tropics and are warm for much of the year. The average temperature is about 73 °F (23 °C) near the tropics and 81 °F (27 °C) near the equator. Mountain areas in New Guinea and a few other high islands are somewhat cooler. The tallest mountains in Hawaii, New Guinea, and New Zealand are snow covered the year around.

Rainfall varies greatly throughout Oceania. Most islands have both a wet season and dry season. The wet season lasts from December to May in the south and from May to December in the north. High islands often have more than 150 inches (381 centimeters) of rain a year. During the wet season—and especially from January to March in the south and from July to October in the north—islands can experience cyclones, hurricanes, and typhoons. In Kiribati, rises in sea level result in king tides, high and strong surges of water that flood the land. Earthquakes in the Pacific sometimes create a series of large, destructive ocean waves called a tsunami.

El Niño, a periodic change in the interaction between the atmosphere and the tropical Pacific waters that affects all areas of the Pacific, brings droughts, heavy rainfall, flooding, frequent cyclones or typhoons, and altered sea levels to the Pacific Islands.

Economy

The Pacific Ocean is of great importance to the people who live on the Pacific Islands and the Pacific Rim. The ocean provides low-cost sea transportation, extensive fishing waters, offshore oil and gas fields, minerals, and sand and gravel for the construction industry. Much of the world’s fish catch comes from Oceania. Offshore oil and gas reserves provide a vital supply of energy for Australia, China, New Zealand, Peru, and the United States. In addition, the United States has military bases in Guam, Hawaii, and the Marshall Islands that greatly influence the economies of those areas.

Fiji, Hawaii, and New Zealand have well-developed economies with a large number of agricultural and manufacturing industries. Tourism and government employment are also major sources of income in most of the Pacific. Mining is a major industry in New Caledonia, Papua, and Papua New Guinea.

Most Pacific Islanders have access to land and to food they have grown themselves. They live in what economists call an informal economy, sometimes earning income from selling betel nut, copra (the dried meat of the coconut), fish, fruits, kava, local crafts, sweet potato, taro, and yams.

Most Pacific Island countries receive financial aid. Major aid contributors include Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and such organizations as the Asian Development Bank, the European Union, and the United Nations. Many Pacific Islanders also receive support from family members living overseas.

Agriculture

is one of the main industries of Oceania. On many of the low islands, the soil is too poor and the rainfall too light for many plants to grow well. On these islands, the main resources are breadfruit, coconuts, pandanus, and swamp taro. Many of the high islands have fertile soil and plentiful rainfall. These conditions allow a wide variety of plants and trees to grow, including mango, pineapple, sugar cane, sweet potatoes, taro, and yams. The coconut tree, paper mulberry, and ti plants are important sources of fiber for weaving and other crafts.

In Hawaii, New Caledonia, and New Zealand, nonnative people own most of the land. In the rest of the region, much of the farmland belongs to the community.

Copra was once the Pacific Islands’ most important agricultural product. It can be used to make such products as coconut oil, margarine, and soap. Today, some island countries use coconut trees for timber and are starting to use coconut oil for fuel. In such areas as Fiji and Hawaii, sugar became an important crop in the 1800’s, and widespread pineapple production began in the 1900’s. Today, pineapples and sugar cane have declined in importance. Farmers in New Guinea grow cocoa and coffee for export. Loggers cut trees on many islands, particularly in Melanesia, for sale in Asia.

Mining and manufacturing.

Several of the high islands, as well as many seabed regions, have valuable deposits of such important minerals as chromium, copper, gold, iron, manganese, and nickel.

Mining for gold and nickel is especially important in New Caledonia and New Guinea. Papua New Guinea benefits from oil fields. Some raised coral atolls, including Banaba and Nauru, once held deep deposits of phosphate, a mineral useful for agriculture. However, the deposits were almost completely mined out by Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

In many urban centers, manufacturing industries make cardboard, clothes, cooking oil, lumber, packaged foods, soap, and sugar. Some of these industries are controlled by foreign businesses that establish manufacturing plants in tax-free zones in the Pacific.

The tourist industry

is vital to the economies of the Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Hawaii, New Zealand, Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands, Samoa, and Vanuatu. Tourism and trade have influenced some artistic practices, as many islanders make traditional handcrafted products to sell. Some islanders fear that further growth of the tourist industry could destroy the natural charm and traditional way of life of the Pacific. Some island groups have therefore attempted to control the development of the tourist industry.

Transportation.

Canoes have traditionally been the primary mode of transportation in Oceania. They range from small canoes that carry one or two people to large canoes that can carry hundreds. Islanders use canoes to travel, fish, and transport goods between islands. Canoes were traditionally outfitted with sails. Some today use outboard motors instead. All island countries depend on sea transport for the shipment of food, manufactured goods, and raw materials.

In the early 1900’s, bicycles became a popular means of transportation. The development of new roads in towns, cities, and other areas later led to an increase in the use of automobiles. In such cities as Honolulu in Hawaii and Suva in Fiji, traffic jams often occur.

Many islanders depend on air transportation. Most island countries have access to local or regional airlines.

Communication.

The arrival of high-frequency radio technology in the 1920’s allowed regional communication in the Pacific Islands to grow. In the late 1970’s, satellites drastically improved communication among the islands. Today, cell phones have become a popular mode of communication in many countries.

Radio stations, newspapers, and television broadcasting stations can be found throughout the Pacific Island countries. Most islands also have access to satellite television broadcasts from Australia, Fiji, New Zealand, or the United States. Internet facilities are available in metropolitan centers. Vast online networks link people in the islands and overseas.

History

Early cultures.

People have lived in Australia and on some islands in Melanesia, including New Guinea, for at least 50,000 years. The original settlers are believed to have come from Southeast Asia. Additional migrants to the western islands are believed to have come from southern China and Taiwan about 6,000 years ago. The descendants of these groups and of the earlier Melanesian settlers expanded throughout Micronesia and Polynesia. The ancestors of the Pacific Islanders were some of the earliest skilled navigators. Their navigational skills allowed them to explore and settle in the largest region on Earth. The Pacific was the last uncolonized place on Earth suitable for human settlement.

European explorers.

In 1513, the Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa became the first European to sight the eastern Pacific Ocean. He saw it from Panama. In 1520, the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan began to sail westward across the Pacific. In 1521, he reached Guam. After this voyage, many Europeans sailed the Pacific in search of wealth, knowledge, and contact with other cultures.

Spanish and Portuguese mariners were followed by Dutch explorers, including Abel Janszoon Tasman, who arrived in New Zealand in 1642. The French scientist and explorer Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville, sailed the Pacific in the late 1700’s. The most acclaimed explorer of the 1700’s was Captain James Cook of the British Royal Navy. Between 1768 and 1779, he located and accurately mapped many islands of the Pacific, including Hawaii and New Caledonia.

Missionaries, traders, and settlers.

Roman Catholic missionaries reached the islands of Guam and the Northern Marianas in 1668. However, missionaries did not become established in the rest of the Pacific until the early 1800’s. Missionaries trained islanders in such places as Hawaii, Samoa, Tahiti, and Tonga to assist in the spread of Christianity. Many Polynesian missionaries were sent to Micronesia and Melanesia to convert others. Although many missionaries introduced improvements to the islands, others concentrated largely on doing away with native customs and traditions.

European and American settlers spread throughout the islands in the 1800’s. Some of these settlers started coconut, coffee, pineapple, or sugar plantations. As the global demand for labor increased, slave traders called blackbirders kidnapped islanders to work on plantations in Australia and South America. Europeans also brought diseases against which the islanders had no resistance. On some islands, epidemics greatly reduced the population.

Colonial rule.

By the late 1800’s, France, Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States competed for control of islands in the Pacific. After Spain’s defeat in the Spanish-American War of 1898, Germany and the United States took over the Spanish possessions in Micronesia. By the early 1900’s, Germany also held parts of Nauru, New Guinea, and the Samoa Islands. The United States controlled the rest of the Samoa Islands and Hawaii. France controlled New Caledonia and French Polynesia and shared control of the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) with the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom held Fiji, the Gilbert and Ellice islands (now Kiribati and Tuvalu), Papua, the southern Solomons, and Tonga.

After Germany’s defeat in World War I (1914-1918), Japan received control of the German possessions in Micronesia, New Zealand took over German Samoa, and Australia received control of northeastern New Guinea. Through all these changes of rule, many islanders had little or no voice in the government. Some islanders, especially chiefs and kings, used the colonial governments to further their own ambitions.

World War II (1939-1945).

Japan increased its power in the Pacific after World War I. In 1941, Japanese bombers attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, marking the beginning of World War II in the Pacific. By mid-1942, Japanese troops had captured islands as far east as the Gilbert Islands and as far south as the Solomons. The United States and its allies then began to drive the Japanese off these islands. Bloody battles were fought at Tarawa in the Gilberts and on Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima (now Iwo To), and other islands. In 1945, Japan surrendered and lost its Pacific empire. Loading the player...

Attack on Pearl Harbor

Nuclear testing.

After World War II, the United States began nuclear weapons tests on Bikini and Enewetak atolls in the Marshall Islands and on Kiritimati Atoll (Christmas Island) and Johnston Island in Polynesia. The United Kingdom conducted similar tests on Kiritimati Atoll and Malden Island in what is now Kiribati.

Nuclear testing forced many islanders from their home islands. Some islanders and American personnel were exposed to radiation as a result of the tests. This exposure caused a number of birth defects and illnesses, including cancer.

In 1963, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union signed a treaty banning aboveground nuclear tests. The United States and the United Kingdom then stopped their tests in the Pacific. France, however, did not sign the treaty and conducted about 200 nuclear weapons tests in French Polynesia after 1965. French nuclear testing triggered a protest movement against nuclear testing and colonial rule in the 1970’s. In 1985, the South Pacific Nuclear-Free Zone Treaty banned nuclear testing in the region. However, French nuclear testing did not end until 1996.

Pacific alliances and independence movements.

In 1971, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Nauru, Tonga, and Western Samoa organized the South Pacific Forum (now the Pacific Islands Forum) to promote cooperation among the islands in such matters as international relations and trade. Australia and New Zealand were included as Forum members because of their location and their involvement in the affairs of the region. Forum members hoped that by cooperating with one another they would become less dependent on Western nations. The forum has grown to include 16 member states.

Since 1962, a number of islands or island groups have become independent. The United Kingdom granted full independence to Fiji and Tonga in 1970 and to the southern Solomon Islands and to Tuvalu (formerly Ellice Islands) in 1978. In 1979, the independent nation of Kiribati was formed from a British colony that included the Gilbert Islands. In 1980, the New Hebrides—which had been ruled jointly by the United Kingdom and France—became independent as Vanuatu.

In 1965, the Cook Islands—a territory of New Zealand—gained a form of self-government. The islands took control of internal affairs, and New Zealand continued to handle external affairs as requested. Another New Zealand territory, the island of Niue, gained self-government in 1974.

After World War II, the United Nations (UN) decided that four areas in the Pacific should be governed as trust territories until they were ready for independence. New Zealand administered Western Samoa as a trust territory until 1962, when it gained independence. Western Samoa changed its name to Samoa in 1997. Australia, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand governed Nauru as a trust territory until 1968, when it became independent. Australia governed the Trust Territory of New Guinea until 1973, when it became part of the self-governing territory of Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea gained full independence in 1975.

The United States administered the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, which was divided into four political units. In 1986, all of the Mariana Islands except Guam became a commonwealth of the United States. Guam is a U.S. territory. Also in 1986, the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia—composed of all of the Caroline Islands except the Palau group—became independent nations in free association with the United States. Under free association, their governments control all of their internal and foreign affairs. The United States is obligated to defend the islands in emergency situations. In 1994, the Palau Islands became the independent nation of Palau. The new country also had an arrangement of free association with the United States.

Since the 1970’s, New Zealand’s Māori people, as well as the Indigenous peoples of Hawaii, have called for increased sovereignty (self-rule). Similar native-rights movements have formed in such regions as Guam, New Caledonia, Papua, and French Polynesia, which are still controlled by foreign powers.

Recent developments.

In the 1990’s and 2000’s, many Pacific countries struggled with conflicts between traditional cultural concepts and new ideas about democracy and free trade. Pacific leaders have worked to increase regional cooperation and security through a number of international agencies. The idea of a strong, diverse oceanic community encompassing the many island cultures has continued to gain popularity. Some Pacific groups overseas have dropped the terms Poly-, Mela-, and Micro- and simply call themselves Nesians.