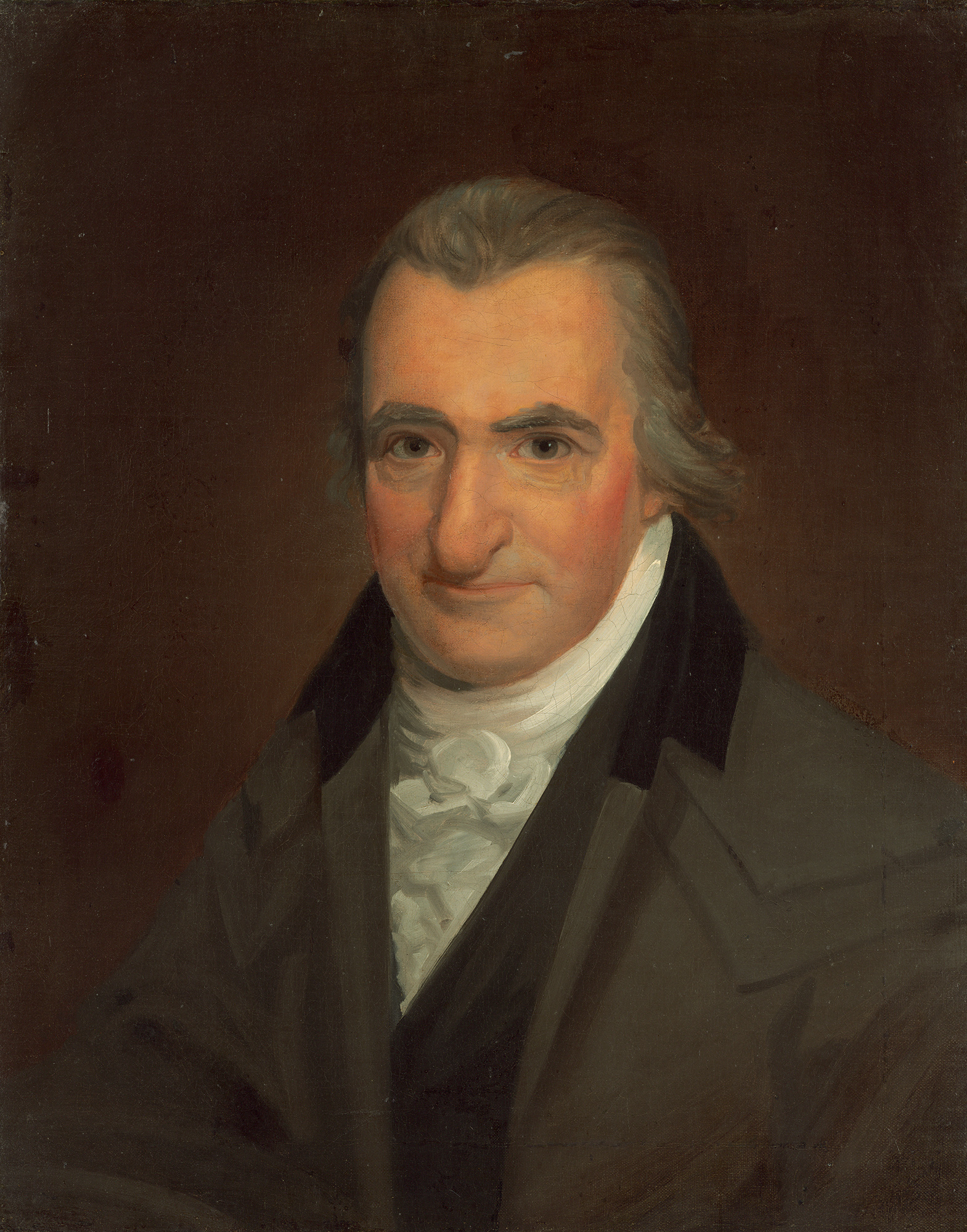

Paine, Thomas (1737-1809), was a famous pamphleteer, agitator, and writer on politics and religion. His writings greatly influenced the political thinking of the leaders of the American Revolution (1775-1783), and he became a famous figure in Paris during the French Revolution (1789-1799). “I know not,” wrote former President John Adams in 1806, “whether any man in the world has had more influence on its inhabitants or affairs for the last thirty years than Thomas Paine.”

Paine’s opinions and personality aroused strong feelings in others. Some admired him greatly, but others hated him fiercely. Many historians regard Paine, as he regarded himself, as a patriot who did much for America and asked nothing in return. He stated clearly and concisely political ideas that others accepted and supported. Yet Paine died a social outcast.

Early life.

Paine was born on Jan. 29, 1737, in Thetford, England. His family was poor, and he got little schooling. At the age of 13, Paine was apprenticed to his father to learn the trade of corset-making. He went to sea at the age of 19. Paine later served as a customs collector in London, but he was discharged. Paine’s first wife died, and he was separated legally from his second wife. Paine was unemployed and poor in 1774, but he was also socially connected. He gained the friendship of Benjamin Franklin, then in London, who advised him to go to America.

American revolutionary.

Paine arrived in America with letters of recommendation from Franklin. Paine soon became contributing editor to the Pennsylvania Magazine, and he began working for the cause of independence. In 1776, he published his pamphlet Common Sense a brilliant statement of the colonists’ cause. This pamphlet demanded complete independence from Britain and the establishment of a strong federal union. It also attacked the idea of monarchy and inherited privilege. Paine asserted that the American Revolution would begin a new era in world history. “The birthday of a new world is at hand,” he wrote. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and other colonial leaders read the pamphlet, as did hundreds of thousands of ordinary Americans. Common Sense became the most widely circulated pamphlet in American history to that time.

In December 1776, Paine followed Common Sense with a series of pamphlets called The American Crisis. The first of these pamphlets began, “These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country. … Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered.” Washington had the pamphlet read aloud to his soldiers. Paine’s bold, clear words encouraged the Continental Army during the darkest days of the war.

Paine served as a soldier in 1776. He also worked with a group of Pennsylvanians to create a democratic constitution for the state. In April 1777, he became secretary to the Congressional Committee of Foreign Affairs. In exposing questionable actions by Silas Deane, the American commissioner to France, Paine also exposed diplomatic secrets. This earned him powerful enemies, and Paine was forced to resign his position.

French revolutionary.

Paine went to France in 1787 and then to England. While in England in 1791 and 1792, he published his famous Rights of Man, replying to Edmund Burke’s attack on the French Revolution (see Burke, Edmund ). William Pitt’s government suppressed this work, and Paine was tried for treason and outlawed in December 1792. But he had returned to France.

The National Assembly of France made Paine a French citizen on Aug. 26, 1792. Paine became a member of the National Convention. But his faction, called the Girondists, lost power in the Convention. Then he was expelled from the Convention, deprived of his French citizenship, imprisoned for more than 10 months, and nearly executed (see Girondists ). The American minister, James Monroe, claimed him as an American citizen and obtained his release.

While in prison, Paine worked on Age of Reason. It stated his belief in deism—the belief that God existed independently of the world and had no interest in it—but his opponents labeled it the “atheist’s bible.” It began: “I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life.” Although Paine believed in God, he disagreed with many accepted church teachings and saw the established churches of Europe as obstacles to social change. His views on religion made him one of the most controversial people of his time. The controversy lasted beyond his lifetime, and his writings were both denounced and celebrated throughout the 1800’s.

Dies neglected.

In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson arranged for Paine’s return to the United States. Paine found that people remembered him more for his opinions on religion than for his role in the American Revolution. During his last years, Paine was poor, ill, and a social outcast. He died on June 8, 1809. He was buried on his farm in New Rochelle, New York, but 10 years later his remains were moved to England. The location of his grave is unknown.