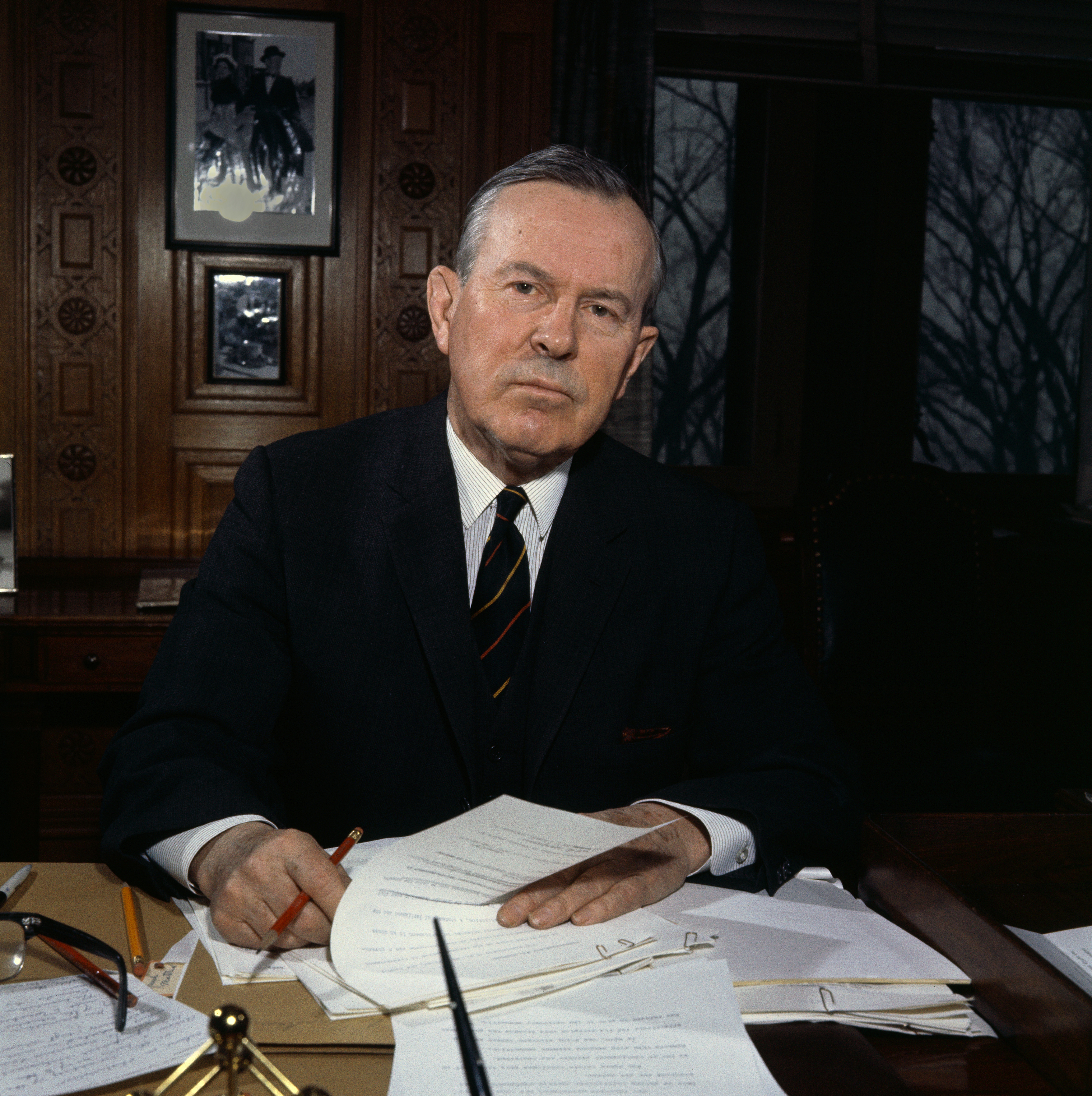

Pearson, Lester Bowles (1897-1972), a former baseball and hockey player and university professor, served as prime minister of Canada from 1963 to 1968. He succeeded John G. Diefenbaker, whose Conservative government fell during a dispute between Canada and the United States. Diefenbaker had refused to allow atomic warheads on defense missiles provided by the United States. Pearson, a Liberal, believed that Canada had agreed to accept the warheads and should do so. Pearson resigned as prime minister in 1968. He was succeeded by Pierre Trudeau, the minister of justice in Pearson’s Cabinet.

Long before taking office as prime minister, Pearson had won fame as an international statesman. He was the first Canadian to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. As Canada’s secretary of state for external affairs, Pearson had helped establish the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), an alliance of Western nations. He also served on a United Nations commission that drew up cease-fire plans in the Korean War. Pearson then became president of the UN General Assembly. He later played a leading role in ending a war in Egypt over control of the Suez Canal.

At the UN and NATO, Pearson showed great ability at working behind the scenes to put ideas into action. He could work with people of any temperament. He eased many tense moments with a well-chosen remark. The public became familiar with Pearson’s sporty bow ties and his nickname, “Mike.” However, Pearson had a deep personal reserve that people found difficult to penetrate.

When Pearson became leader of the Liberal Party in 1958, one newspaper described him as “eloquent as a professor of algebra.” Pearson admitted that he lacked the ability to inspire audiences with speeches. He spoke with a slight lisp, which hurt his efforts to impress his listeners. He worked hard to make himself a better public speaker, but did not enjoy making speeches.

“There are some things in politics I don’t like, never have liked, and never will like,” Pearson said. “The hoopla, the circus part of it, all that sort of thing. It still makes me blush.”

Early life

Boyhood.

Lester Bowles Pearson was born on April 23, 1897, in Newtonbrook (now part of Toronto), Ontario. He was the son of Edwin Arthur Pearson, a Methodist minister, and Annie Sarah Bowles Pearson. His father’s father also had been a minister. Lester had an older brother, Marmaduke, and a younger brother, Vaughan. Edwin Pearson had a great interest in sports, especially baseball, and passed his enthusiasm on to Lester. The boy became a star athlete. He also was an excellent student.

Education and war service.

In 1913, Pearson entered the University of Toronto. He majored in history. World War I began in August 1914. The following March, at the age of 17, Pearson enlisted in the Canadian Army Medical Corps as a private. He completed his training in England and was sent to Thessaloniki, Greece, in 1915. He served in the Balkan area of southeastern Europe for a year and a half.

While Pearson was serving as a stretcher-bearer, some wounded British soldiers called the youth “Mike” because he looked Irish, and the nickname stayed with him. In 1917, Pearson received a lieutenant’s commission in the infantry. That same year, he transferred to the British Royal Flying Corps as a pilot with the rank of flight lieutenant. Canada had no air corps at the time. Pearson returned to Canada in April 1918 because of injuries he suffered after being struck by a bus in London. He served for the rest of the war as a ground instructor at a Canadian base of the Royal Flying Corps.

After World War I ended in November 1918, Pearson returned to the University of Toronto. He graduated with honors in 1919. He then studied law for several weeks in Toronto. Next, Pearson took a job stuffing sausages in the Hamilton, Ontario, plant of Armour and Company, a meat-packing firm. During this period he played semiprofessional baseball. He then worked as a clerk in Armour’s Chicago plant.

In 1921, Pearson received a scholarship from the Massey Foundation, which sent Canadians overseas to study. He studied history at Oxford University in England from 1921 to 1923. Pearson starred on Oxford’s hockey team and played on the British Olympic team. He received a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree from Oxford. From 1923 to 1928, he taught history as a lecturer and then as an assistant professor at the University of Toronto.

On Aug. 22, 1925, Pearson married Maryon Elspeth Moody (1902-1989) of Winnipeg, Manitoba. She had been one of his students at the university. The Pearsons had two children—Geoffrey Arthur Holland Pearson, who became a Canadian foreign service officer, and Patricia Lillian Pearson. Maryon Pearson disliked public life. But she was proud of her husband and anxious for his success, and she played an active role in his election campaigns. Pearson once declared: “I couldn’t have carried on without her.”

Public career

Early diplomatic service.

A great turning point in Pearson’s life came in 1928. He entered the diplomatic service during the administration of Liberal Prime Minister W. L. Mackenzie King, and served as a first secretary in the department of external affairs.

From 1930 to 1935, during the administration of Conservative Prime Minister R. B. Bennett, Pearson took part in several international conferences. Bennett particularly praised Pearson for his work on two Canadian economic commissions. Pearson received the Order of the British Empire, an award for public service from the British government.

King returned to power as prime minister in 1935. For six years, Pearson served as first secretary in the Canadian high commissioner’s office in London. He returned to Ottawa in 1941 and for one year was assistant undersecretary of state for external affairs. In 1942, King assigned Pearson to the staff of the Canadian embassy in Washington, D.C.

In 1943, Pearson headed a United Nations commission on food and agriculture. This work led to the creation of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization in 1945. As chairman of another UN committee in 1943, he helped organize the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). Pearson represented Canada at UNRRA meetings in 1944, 1945, and 1946. In January 1945, King appointed him Canadian ambassador to the United States. Pearson held this post until October 1946, when he returned to Ottawa as undersecretary of state for external affairs.

Pearson served as senior adviser of the Canadian delegation to the San Francisco conference that signed the United Nations Charter in June 1945. The Western nations favored him to be the first UN secretary-general, but the Soviet Union vetoed him.

Secretary of state for external affairs.

In September 1948, Pearson was appointed secretary of state for external affairs of Canada. Canadian Cabinet members must be members of Parliament, so Pearson ran for a seat in the House of Commons the following month. The district of Algoma East in Ontario elected him to the House of Commons, and he won reelection in succeeding elections through the years. As Canada’s secretary of state for external affairs, Pearson headed most of his country’s delegations to the UN General Assembly from 1948 to 1956. King retired in November 1948, and Louis St. Laurent succeeded him as Liberal Party leader and prime minister.

In April 1949, Pearson represented Canada at ceremonies setting up NATO. He had been one of the principal architects of the alliance. Pearson emphasized that NATO, although it was established to ward off Communism, must also work for social, economic, and political progress. “Our treaty,” Pearson declared, “is … the point from which we start for yet one more attack on all those evil forces which block our way to justice and peace.”

Pearson attended many other international conferences as part of his duties. He placed great importance on relations between developed countries, such as Canada, and less developed nations, such as India. He also worked to strengthen the nonmilitary aspects of NATO. In addition, Pearson tried to improve the UN. He served as president of the UN General Assembly in 1952 and 1953.

In October 1956, France, the United Kingdom, and Israel invaded Egypt, which had seized the Suez Canal. The UN accepted Pearson’s proposal to set up an emergency military force to end the fighting and supervise a cease-fire. The UN troops quickly restored peace before the fighting could turn into a major war. On Oct. 14, 1957, Pearson became the first Canadian to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

Liberal Party leader.

In 1957, St. Laurent’s government fell to the Conservatives, led by John G. Diefenbaker. After resigning as prime minister, St. Laurent also stepped down as Liberal Party leader. Pearson quickly decided to run for party leader. Although some Liberals considered him to be too inexperienced in domestic affairs, his fame as a statesman and his popularity in Parliament brought him victory in the race. The Liberal Party chose Pearson as its leader by a large majority in January 1958.

“No one ever started off worse than I did,” Pearson said later. His advisers persuaded him to seek a parliamentary vote of no confidence in the new Conservative government. Pearson demanded that Prime Minister Diefenbaker return the government to the Liberals without an election. This demand gave Diefenbaker, a master of parliamentary maneuvering, a chance to attack Pearson and the Liberals. Diefenbaker then dissolved Parliament and called an election in March 1958. Under Pearson, the Liberals went down to one of their worst defeats in history. They won only 49 of the 265 seats in the House of Commons.

After some initial discouragement, Pearson organized his tiny forces to mount an increasingly strong attack on the Diefenbaker government. While sharply criticizing the government in Parliament, Pearson and other Liberals also reorganized their party to give it a progressive and decisive image. These developments helped increase the popularity of the Liberal Party. In addition, the Diefenbaker government was handicapped by high unemployment in Canada.

As a result of Pearson’s vigorous leadership, the Liberals doubled their parliamentary strength in the June 1962 elections. The Conservatives fell short of an absolute majority in Parliament, but they still had more seats than any other party.

Prime minister.

Early in 1963, a dispute over defense policy strained relations between Canada and the United States. The question was whether Canada had agreed in 1959 to accept atomic warheads for missiles supplied by the United States. Pearson and the Liberals contended that Prime Minister Diefenbaker should accept the warheads, but Diefenbaker refused to do so. The Conservative government fell apart, with three ministers resigning, and was defeated by a vote of no confidence taken in February 1963.

In the elections of April 1963, the Liberals won 129 seats in the House of Commons, four short of an absolute majority. However, the small opposition parties promised to support Pearson. The Progressive Conservatives won only 95 seats, and Diefenbaker resigned. Pearson became prime minister of Canada on April 22, 1963.

Pearson worked quickly to improve Canadian relations with the United Kingdom and the United States. He accepted nuclear warheads from the United States and took action to save a stalled treaty concerning the Columbia River. Pearson got along well with President John F. Kennedy of the United States, but he was less happy with Kennedy’s successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson. The United States became increasingly involved in the Vietnam War during the mid-1960’s. Pearson believed the war would end badly for U.S. foreign policy, and he urged the United States to seek a peaceful solution to the conflict.

Pearson faced serious domestic problems when he became prime minister. Disputes between French-speaking and English-speaking Canadians threatened national unity. Many French Canadians complained that they did not have equal opportunities and rights. One organization, the Quebec Liberation Front, demanded independence from Canada for the province of Quebec. This secret terrorist group used bombings and other forms of violence against the national government. Fortunately for Pearson, the Canadian economy boomed during the 1960’s. This prosperity permitted his government to provide increased social services.

In 1965, Pearson called a national election because he wanted an absolute Liberal majority in the House of Commons. He kept control of the government, but the Liberals failed to win a majority.

In April 1968, at the age of 71, Pearson resigned as prime minister and as head of the Liberal Party. Pierre Trudeau succeeded Pearson. In August 1968, Pearson became head of a World Bank commission. The commission was set up to assist the economic progress of developing countries.

Pearson remained in good health until 1970, when he had an operation for cancer that resulted in the removal of an eye. He died of cancer at his home in the Ottawa suburb of Rockcliffe Park on Dec. 27, 1972. He was buried near Wakefield, Quebec.