Phonograph is a device that reproduces sounds that have been recorded on audio records. Phonographs are also called record players or gramophones. Until the mid-1980’s, they were the most common device for listening to music and other sound recordings. Today, most people listen to digital music stored on computer files or on compact discs (CD’s) instead of records. Digital music can reproduce sounds more faithfully than records can, and music files can be distributed easily over the Internet. However, some people prefer the sound of phonograph records. They may also enjoy collecting and playing records.

How phonographs work.

Phonographs play records that contain an analog (likeness) of the original sound waves. The analog is stored as jagged waves in a spiral groove on the surface of a disc. As the disc rotates on the phonograph, a needle, called a stylus, rides along the groove. The waves in the groove cause the stylus to vibrate. The vibrations then are transformed into electric signals and converted back into sound by speakers.

In a stereophonic phonograph, the stylus responds to two separate sets of waves—one on either side of the groove. These two sets of waves correspond to the two channels through which the sound signals are ultimately distributed.

Most phonograph records are thin, black, vinyl discs with a diameter of 12 inches (30 centimeters). They are played at 331/3 revolutions per minute (rpm) and can hold about 30 minutes of sound per side. These records are often called long-playing (LP) records or simply LP’s, to distinguish them from records that hold fewer minutes of sound. Some records play at 45 rpm or 78 rpm.

Parts of a phonograph.

The main parts of a phonograph are (1) the turntable, (2) the drive system, (3) the stylus, (4) the cartridge, (5) the tone arm, and (6) the amplifier. The turntable is a flat plate on which the record sits. It is usually made of metal and covered with rubber or plastic. The drive system spins the turntable. In a direct drive system, the turntable is mounted directly on the motor shaft. In a belt drive system, the motor rotates a pulley. A belt goes around the pulley and the turntable rim to spin the turntable.

The stylus is a piece of diamond or extremely hard synthetic material shaped like a cone. It vibrates as it rides in the record groove. The stylus is suspended from one end of a flexible strip of metal. The other end of the metal strip is attached to the cartridge. The cartridge receives vibrations from the stylus and transforms them into electric energy. Most cartridges generate voltages when the motion of the stylus moves an electric coil in a magnetic field or moves a magnet near a coil.

The tone arm, also called the pickup arm, holds the cartridge and stylus. The tone arm usually is mounted on a pivot that lets the stylus ride the record groove in an arc across the disc. Wires along the tone arm carry electric signals from the cartridge to the amplifier, which boosts the power of the signals. Speakers convert the signals to sound waves.

How phonograph records are made.

The production of most records begins with a master (original) recording in a studio or concert hall. During recording, engineers can control various aspects of sound quality. See Recording industry (Making a musical recording) .

The next step is the creation of a master lacquer. A lacquer is an aluminum disc coated with nitrocellulose lacquer. A blank lacquer rotates on the turntable of a machine called a record-cutting lathe. A cutting head on the lathe then receives electric signals from the master recording. A cutting stylus on the cutting head cuts a wavy groove that spirals toward the center of the disc.

Next, manufacturers make a metal master from the master lacquer by a process called electroplating. In this process, the surface of the master lacquer is coated with nickel. When separated from the lacquer, this nickel plate forms a metal master—a negative copy that has ridges where the lacquer has grooves. Plating the metal master produces a mother—a positive copy of the lacquer. The mother itself is then plated several times to create multiple negative copies called stampers.

Two stampers, one for each side of the disc, are put in a hydraulic press. A piece of plastic is placed between the stampers and squeezed in the press. Steam softens the plastic, which is imprinted with grooves from both stampers. After imprinting, cool water stiffens the disc.

History.

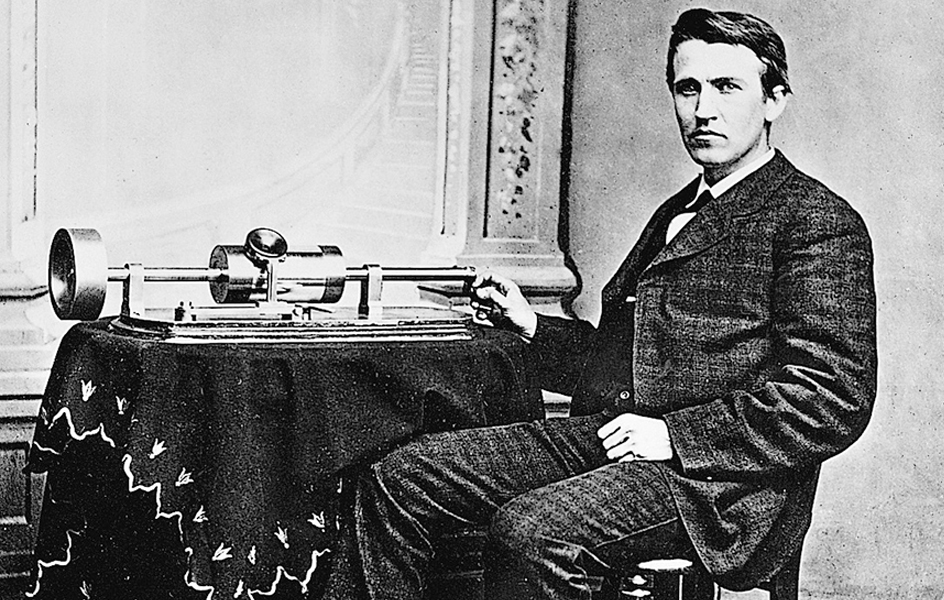

The American inventor Thomas Edison invented the first practical phonograph in 1877. It could record sound on tinfoil wrapped around a metal cylinder. A needle attached to a diaphragm (vibrating disc) was placed against the cylinder, which was rotated with a hand crank. As someone spoke into a mouthpiece, the sound waves made the diaphragm and needle vibrate, causing the needle to make dents in the tinfoil. To play back the sound, another needle attached to a diaphragm was placed against the cylinder as it rotated. The dents in the foil made the needle and diaphragm vibrate, creating sounds roughly like the original sound.

In 1887, Emile Berliner, a German immigrant to the United States, invented the Gramophone—a phonograph that used shellac discs. These discs provided better sound and could be mass-produced more easily than could cylinders.

The first electrically recorded phonograph records appeared in 1925. In addition, manufacturers began producing phonographs with electric motors and amplifiers. In 1948, the plastic 331/3-rpm LP record appeared on the market. The LP held much more sound and was more durable than the clay-shellac 78-rpm discs previously used. In 1949, the 45-rpm disc was introduced.

Stereophonic phonographs and discs appeared in 1958. Previously, records and phonographs were monophonic—that is, they reproduced sounds through only one channel. Stereophonic systems produced sounds that were more lifelike. By the late 1960’s, almost all new phonographs and records were stereophonic.

In the 1980’s, audio CD’s were introduced, and phonograph sales soon plunged. In the late 1990’s and 2000’s, the distribution of music files over the Internet offered an even easier way for fans to listen to songs and albums. But phonographs have not disappeared. Disc jockeys, hip-hop artists, and other musicians sometimes use record turntables for mixing and manipulating sounds from records. In addition, many artists release special editions of their albums in the form of vinyl records. In the late 2000’s and 2010’s, phonograph sales rose sharply—though they did not come close to reaching their peak before CD’s.