Prehistoric animal refers to any animal that existed more than 5,500 years ago, before human beings began recording their history in writing. Some prehistoric animals greatly resembled their present-day relatives. Many ancient creatures, however, were unlike anything alive today. Dinosaurs rank among the best-known prehistoric animals. The largest dinosaurs may have grown 130 feet (40 meters) in length. Other unusual creatures included flying reptiles, sea scorpions 8 feet (2.4 meters) long, and hairy relatives of elephants called mammoths. Not all of these animals lived at the same time.

The long history of animals is recorded by fossils. Fossils are the remains of prehistoric life. They include the bones, shells, and tracks of animals, as well as petrified wood and impressions of leaves. Fossils help scientists called paleontologists learn what prehistoric animals looked like and when, where, and how they lived. Paleontologists use fossils to compare prehistoric animals with living ones. Such comparisons help people understand how ancient and modern animals are related.

The oldest known animal remains date from about 650 million years ago. However, some paleontologists think that simple, tiny animals may have existed much earlier, perhaps as early as 1 billion years ago.

The world of prehistoric animals

Most animals have developed during a time in Earth’s history that scientists call the Phanerozoic Eon, which means “time of visible animal life.” It began 539 million years ago and continues to the present day. Scientists divide the Phanerozoic Eon into three eras: (1) the Paleozoic Era, which lasted from 539 million to 252 million years ago; (2) the Mesozoic Era, which lasted from 252 million to 66 million years ago; and (3) the Cenozoic Era, which began 66 million years ago and continues today. Throughout each era, climates kept changing, continents drifted and changed in outline, mountains rose up and were leveled, and sea levels rose and fell. These changes helped determine which living things survived and which died out.

Each of the three eras is divided into shorter intervals called periods. Periods, in turn, can be divided into still shorter intervals called epochs. Different layers of rock with different kinds of fossils formed during each period. Such rocks help scientists understand how Earth’s surface and climates have changed. The fossils tell paleontologists what animals and plants lived during each period.

Early forms of animal life

Animal life evolved and flourished long after other forms of life appeared. Like animals today, prehistoric animals depended on living things that use energy from sunlight to make food, called producers. Today, the most familiar producers are plants. Animals must eat either producers or animals that feed on producers.

The earliest animals

lived in the seas and were probably tiny. Although their bodies were small, they were made up of many cells. Some groups of those cells became adapted for feeding or reproduction, while others helped the animals move and detect changes in their environment.

The first animals are known from fossils preserved in rocks about 650 million to 570 million years old. They include jellyfishes, sponges, worms, and leaflike creatures called sea pens. All these creatures were invertebrates—that is, they had no backbones. Their soft bodies also lacked shells or other hard parts. As a result, few of them were preserved as fossils.

According to fossils found by scientists, animals first become abundant at the beginning of the Paleozoic Era. A tremendous variety of invertebrate animals suddenly developed in the oceans during this time. Unlike earlier animals, many of these creatures had hard shells or tough outer frames to protect them from enemies.

Trilobites ranked among the most common early Paleozoic animals. They were ancient arthropods, the group to which spiders and crabs belong. Most trilobites fed on small food particles from the sand or mud on which they lived. Such food may have included small worms and other bottom-dwelling animals. Another common group of Paleozoic animals, the brachiopods, had shells similar to those of clams. They lived on the sea floor or burrowed in the mud. Brachiopods ate tiny organisms. They fed by opening their shells and filtering food from the water with a comblike organ.

The first animals with backbones,

called vertebrates, probably appeared in the late Cambrian Period, about 500 million years ago. The earliest vertebrates were small. Plates of bone usually protected their heads and much of their bodies. In later vertebrates, a skeleton made up of many bones formed inside the body. The skeleton provided a solid internal frame to which muscles could attach.

The earliest vertebrates had mouths without jaws. They most likely fed on small bits of dead animals or tiny creatures on the sea floor or in the water. In the Silurian Period, beginning about 444 million years ago, vertebrates developed bony jaws and teeth. These mouth parts enabled them to catch and consume larger kinds of food. The vertebrates also developed movable paired fins, enabling them to become more active swimmers.

The Devonian Period, often called the Age of Fishes, began around 419 million years ago. One of the largest Devonian fishes, Dunkleosteus << `DUHNK` uhl AHS tee uhs >>, grew up to 30 feet (9 meters) long. Massive plates of bone protected Dunkleosteus’s head and the front of its body. Its jawbones formed sharp edges for cutting up and eating smaller fish (see Dunkleosteus).

Bony fishes of the Devonian Period had two types of fins, rayed and lobed. Rayed fins consist of a web of skin supported by a skeleton of rods called rays. Fish with this type of fin, known as ray-finned fishes, are fast swimmers. Lobed fins consist of a fleshy stalk fringed with rays. The Devonian Period was the time of greatest abundance for fishes with this type of fin, called lobe-finned fishes. Lobed fins enabled the creatures to crawl along the bottom of the sea or over land. Many lobe-finned fishes also had lungs with which they gulped air when there was not enough oxygen in the water. All land-living vertebrates, including human beings, descended from these fishes.

The move onto land.

Animals first established themselves on dry land by the beginning of the Devonian Period. The oldest known land animals were arthropods, including scorpions, spiders, and mites. Vertebrates probably first moved onto land near the end of the Devonian Period. The sturdy fins of lobe-finned fishes evolved into the legs of land-living vertebrates, with ankles, wrists, fingers, and toes suitable for leaving the water. Lungs became full-time suppliers of oxygen.

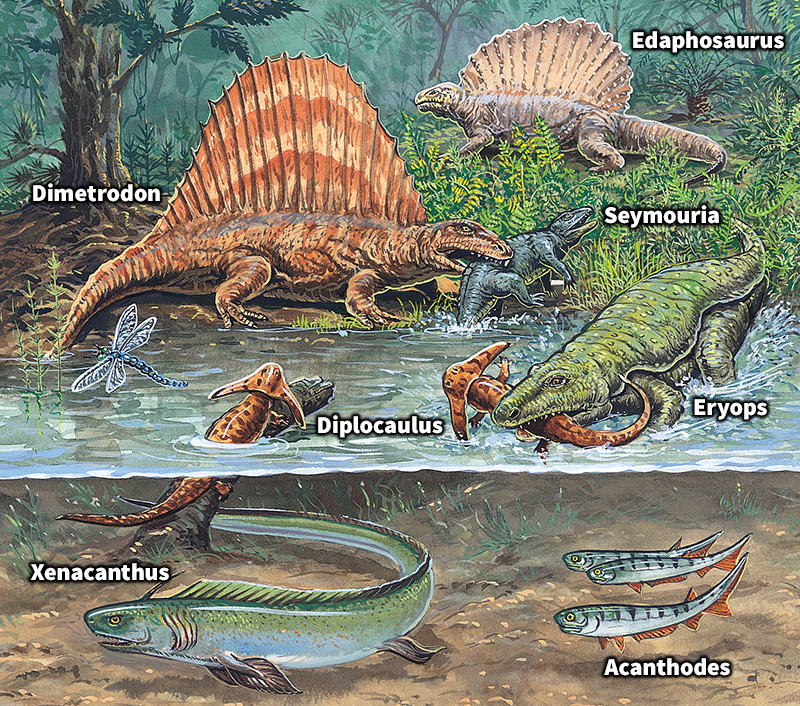

Four-footed land vertebrates are known as tetrapods << TEHT ruh podz >>. The first tetrapods somewhat resembled amphibians, especially in their need to return to the water to lay eggs. However, these animals differed in many ways from modern amphibians, which did not appear until more than 100 million years later. Like the eggs of amphibians, the eggs of early tetrapods were enclosed in a jellylike substance that, if left on land, would dry out and kill the eggs. Thus, these eggs developed and hatched in water, where the young lived until they changed into land-dwelling, air-breathing adults. During the late Paleozoic Era, a great variety of early tetrapods inhabited the shores of lakes and rivers, dividing their lives between land and water. Modern amphibians, such as frogs, are small, but some early tetrapods were large. The meat-eating Eryops << EH ree ops >> grew more than 5 feet (1.5 meters) long and had a big head. Others, such as Ophiderpeton << oh fee DURP uh ton >>, were small and snakelike. See Eryops; Tetrapod.

The earliest insects were wingless and appeared during the Devonian Period. By the end of the Carboniferous Period, around 299 million years ago, many insects had developed wings. They included Meganeura << mehg uh NYUR uh >>, a spectacular animal resembling a dragonfly. It had a wingspan of up to 26 inches (65 centimeters).

During the Carboniferous Period, the first amniotes appeared. Amniotes had an important advantage over earlier land-living vertebrates: they could lay their eggs on land. Amniote eggs were protected by a shell that prevented them from drying out. Special membranes inside the eggs enclosed and protected the developing young in a fluid-filled chamber. This type of egg enabled amniotes to live entirely on land.

The Age of Reptiles

During the Permian Period at the end of the Paleozoic Era, Earth’s climate generally grew warmer and drier. Deserts spread over large areas, displacing many early tetrapods that needed water for their survival. A group of amniotes called synapsids dominated the land. Certain synapsids were the ancestors of mammals. They had some mammalian characteristics, but in other respects they somewhat resembled crocodiles. At the end of the Permian Period, 252 million years ago, about 95 percent of species became extinct, perhaps because of large volcanic eruptions. But a group of amniotes called sauropsids survived and gave rise to the dinosaurs and other reptiles. These animals came to dominate the land, sea, and air throughout most of the Mesozoic Era. This era is often called the Age of Reptiles.

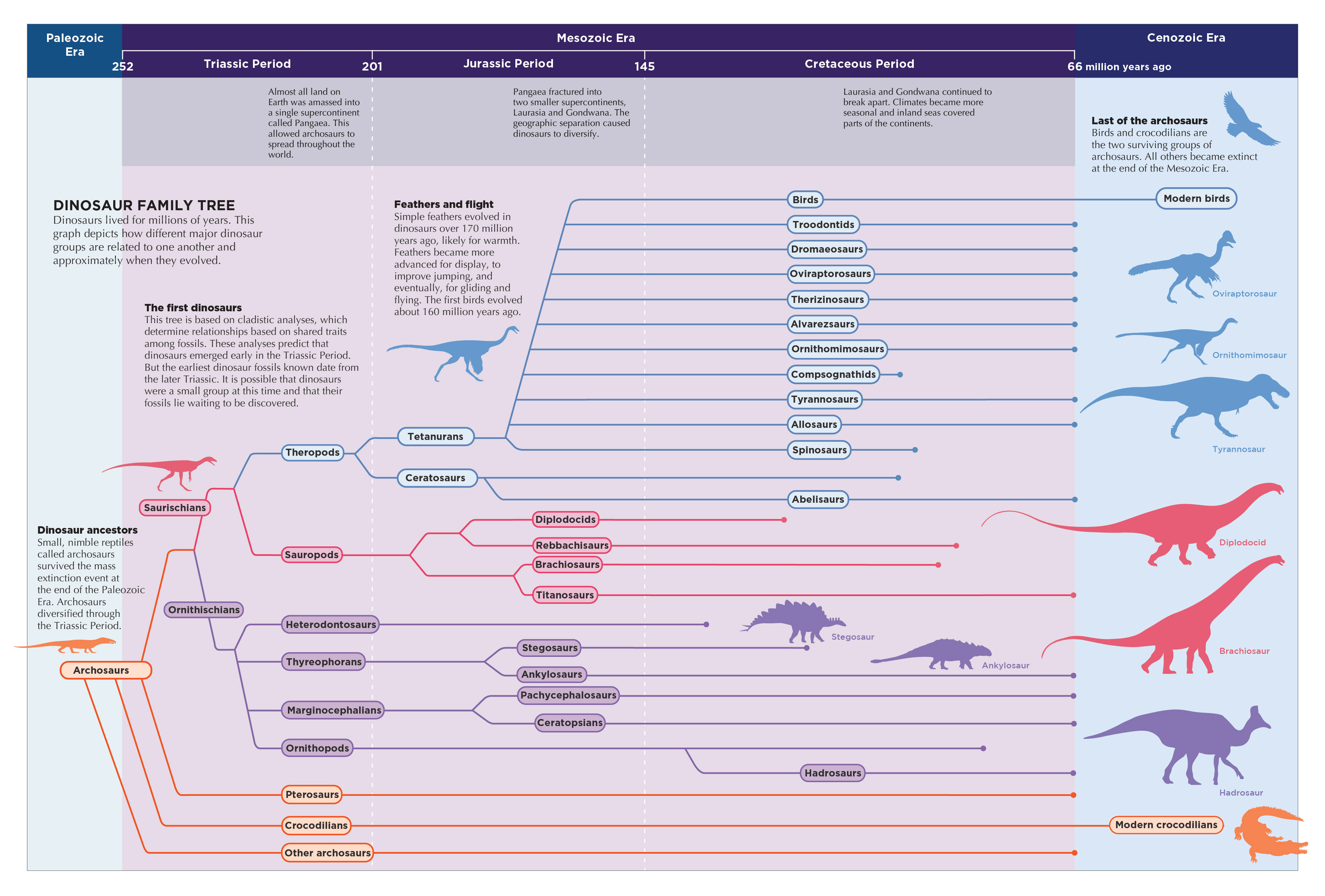

Dinosaurs

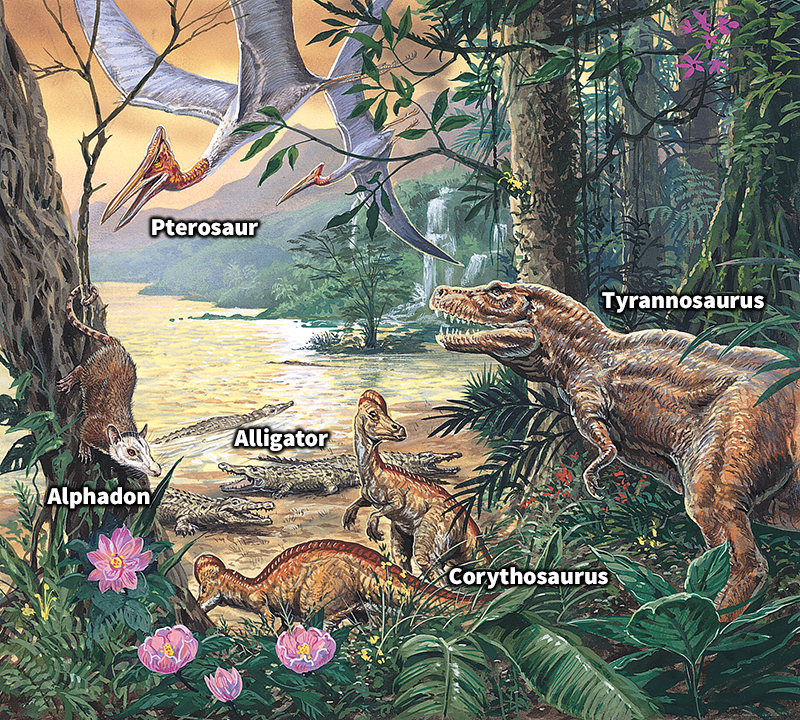

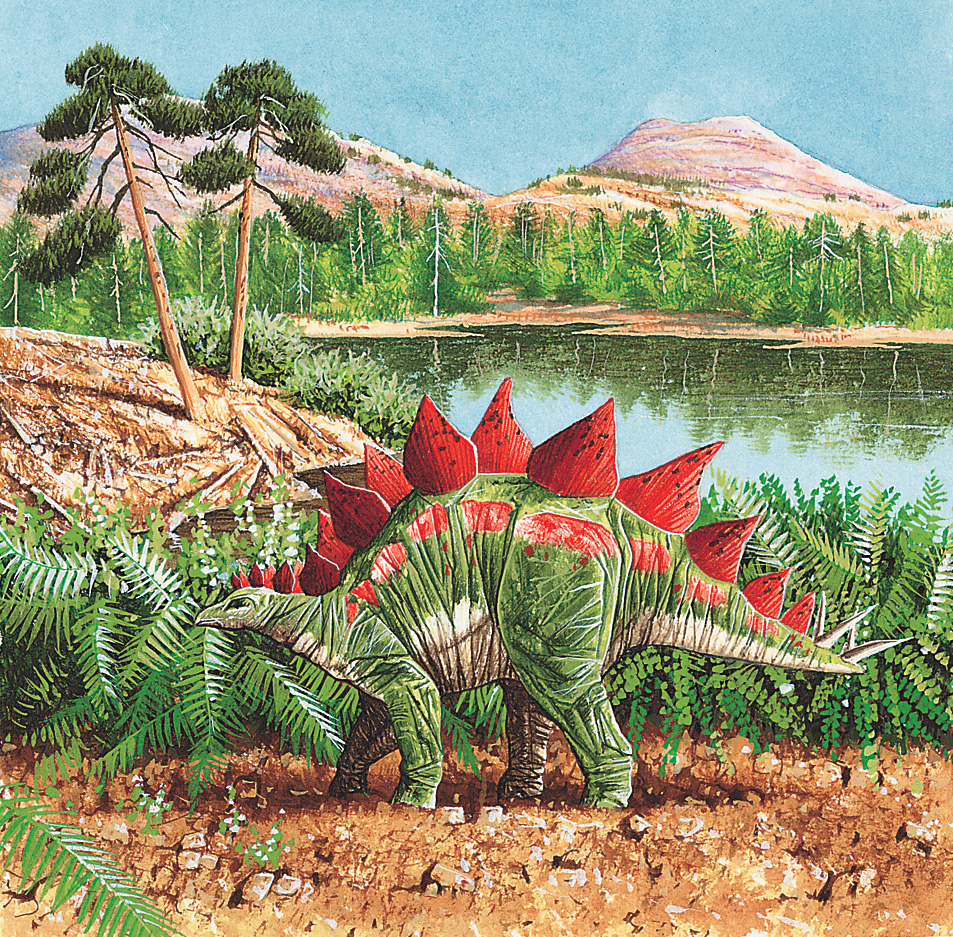

ranked as the dominant animals of the Mesozoic. They varied greatly in size, including some of the largest animals that ever lived. One of the largest, the plant-eating Seismosaurus << SYZ muh `sawr` uhs >>, may have measured about 110 feet (33 meters) in length. The smallest fully grown dinosaurs grew to about 3 feet (1 meter) in length. Many large dinosaurs were probably slow-moving. But scientists believe some dinosaurs, such as Ornithomimus << `awr` nihth uh MY muhs >>, could run fairly fast. For more information about dinosaurs, see Dinosaur.

Other reptiles.

While dinosaurs ruled the land, many kinds of large reptiles inhabited the sea and air. Sea-dwelling reptiles included ichthyosaurs << IHK thee uh sawrz >>, which resembled dolphins in shape and probably could swim fast (see Ichthyosaur). Mosasaurs << MOH suh sawrz >> were enormous sea creatures that lived in the later years of the Cretaceous Period, which ended 66 million years ago. They grew more than 40 feet (12 meters) long. Plesiosaurs << PLEE see uh sawrz >> had four large flippers and a short tail. Many plesiosaurs also had an extremely long neck.

Flying sauropsids called pterosaurs << TEHR uh sawrz >> became the first vertebrates to evolve flapping flight, the kind of flight later used by most birds. Each of a pterosaur’s wings consisted of a membrane of skin supported by a long finger made of hollow bones. Pterosaurs had no feathers, but hairlike structures probably covered their bodies. Some pterosaurs ranked as the largest flying animals of all time, reaching a wingspan of 40 feet (12 meters).

Invertebrates

flourished during the Age of Reptiles, and many new kinds appeared. Numerous species of mollusks lived in the seas. They included clams, snails, squids, and ammonites, which formed spiral-shaped shells. Crustaceans, including lobsters, crabs, and shrimp, became common in the oceans during the Cretaceous Period. All major present-day groups of insects had evolved by Cretaceous times.

Fish

remained abundant in the Mesozoic Era. The first modern kinds of bony fish, called teleosts << TEHL ee `osts` or TEE lee `osts` >>, evolved in the early part of the Mesozoic Era.

Amphibians.

Many of the larger early tetrapods with an amphibian way of life had died out by the end of the Triassic Period. But some kinds persisted well into the Cretaceous Period. Modern amphibians, including frogs and salamanders, first appeared in the early part of the Mesozoic Era.

Birds

evolved from small meat-eating dinosaurs during the Jurassic Period. The earliest birds are thought to have resembled Archaeopteryx << `ahr` kee OP tuhr ihks >>, an animal that lived around 150 million years ago. This crow-sized creature had a skeleton closely resembling that of a small dinosaur. However, it also had fully developed feathers and birdlike wings. It had teeth, a long tail, and three grasping, clawed fingers on each wing. See Archaeopteryx.

The first modern birds appeared in the Cretaceous Period. They developed a toothless beak covered by hornlike material. The tail became short, and the fingers fused into a single structure supporting the wing.

Mammals

evolved from synapsids near the close of the Triassic Period. The first mammals were small, about 6 inches (15 centimeters) long, and probably ate insects and other small animals. These mammals likely had hair covering their bodies. Like their modern descendants, ancient mammals suckled their young from special milk glands. Most Mesozoic mammals probably laid eggs as their ancestors had done. Today, the only egg-laying mammals, called monotremes, are the platypus and the echidnas of Australia and New Guinea.

The two major groups of mammals, marsupials and placentals, first developed in the Cretaceous Period. Both these groups give birth to live young. Marsupial young are born in an underdeveloped state. The young crawl into a special pouch on the mother’s belly, where they continue to develop and grow. Most early marsupials resembled modern opossums.

Placentals give birth to fairly well-developed young. These young grow inside the mother’s body, where they receive nourishment from a special organ called the placenta. Many early placentals resembled shrews.

The Age of Mammals

At the end of the Mesozoic Era, 66 million years ago, nonavian dinosaurs (dinosaurs that were not birds) and other dominant reptiles became extinct. Scientists have found evidence that a huge asteroid hit Earth 66 million years ago. Dust from the impact of this asteroid, as well as soot from the wildfires caused by the impact, would have blocked sunlight from reaching Earth’s surface. Lack of sunlight would have lowered temperatures worldwide and killed many of the plants and animals that dinosaurs ate.

The Cenozoic Era, also called the Age of Mammals, followed the Mesozoic Era and continues today. During this new era the climate grew gradually cooler and drier, and mammals became the dominant animals on Earth. All mammals have warm-blooded bodies covered with hair and are equipped with a variety of teeth for chewing food. Warm-bloodedness, which keeps the mammals’ bodies at constant high temperatures, probably enabled early mammals to adapt more easily than other vertebrates to the cooler, drier climates of the Cenozoic Era.

The development of placentals.

Most modern placentals probably evolved at the beginning of the Cenozoic Era. These creatures had small bodies. For example, Miacis << MY ah sihs >>, a forerunner of all meat-eating mammals, grew about as large as a weasel. The ancient horse Hyracotherium << `hy ` ruh koh THEER ee uhm >>, also called Eohippus << `ee` oh HIHP uhs >>, stood no taller than a dog. Primates started out as small creatures but later evolved into monkeys, apes, and human beings. One of the earliest whales, Pakicetus << pak ee SEE tuhs >>, grew only about 6 feet (1.8 meters) long. Its descendants, however, became some of the world’s largest animals.

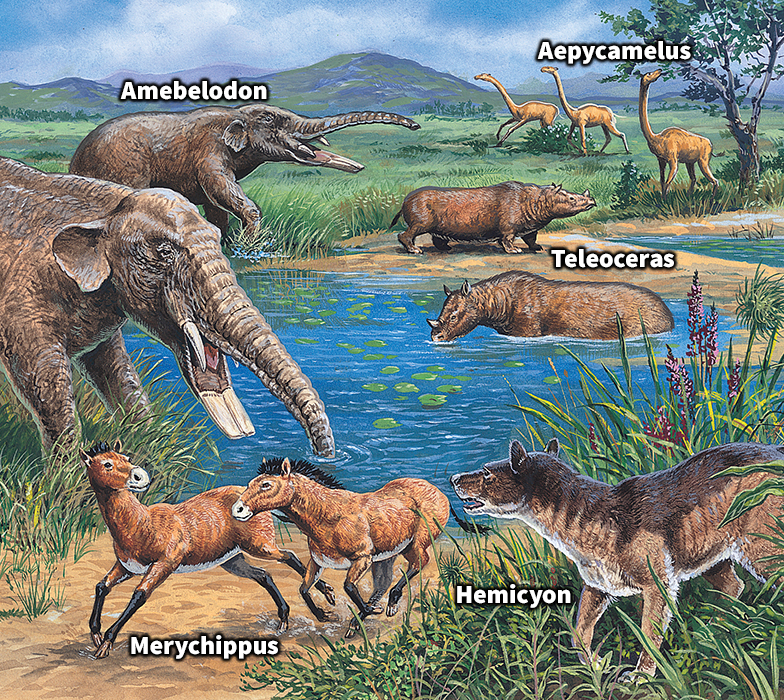

By the middle of the Cenozoic Era, many forests had disappeared. Grasslands spread across many parts of the world, and climates grew cooler and drier. Such hoofed mammals as deer and horses developed teeth suitable for feeding on grass. Many hoofed mammals also had long, slender legs, enabling them to run fast to escape from predators in open country.

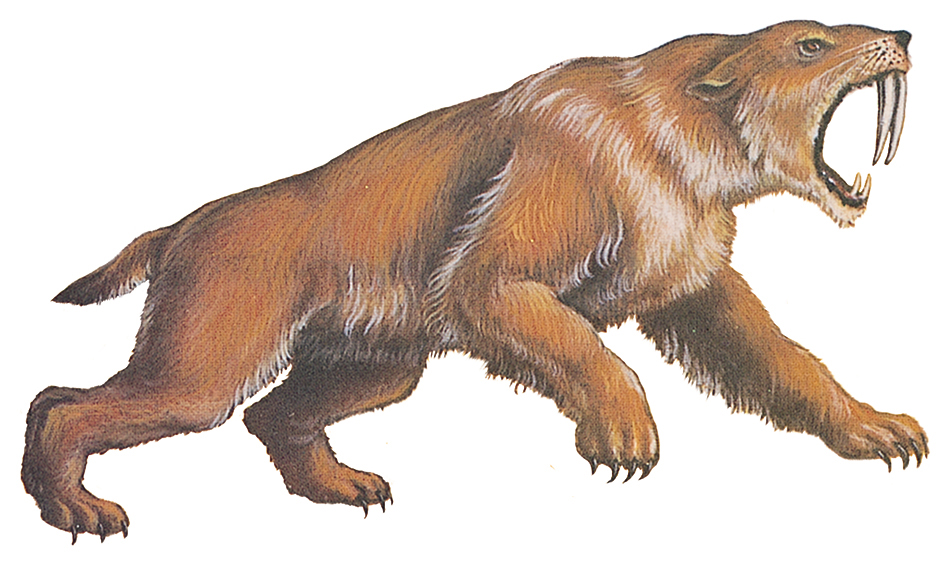

The great increase in plant-eating mammals provided abundant prey for meat-eating mammals. These meat-eaters included the earliest dogs and the saber-toothed cats, large, lionlike predators that could kill their prey with large fanglike teeth. In Africa and Asia, the first apes evolved. Many new kinds of rodents appeared, and they quickly became the most common small mammals.

The distribution of mammals.

About 250 million years ago, all the continents drifted together to form one huge land mass, the supercontinent Pangaea. About 200 million years ago, Pangaea began to break up again into separate continents, which slowly moved to their present positions.

Placental and marsupial mammals may have developed on the northern continents. When Australia separated from South America and Antarctica at the beginning of the Cenozoic, many marsupials and probably only a few placentals had spread there. With few placentals to compete with for food and nesting sites, many kinds of marsupials evolved only in Australia. Some marsupials resembled placental mammals in appearance and habits. They included Diprotodon << dy PROH tuh don >>, which resembled a rhinoceros, and the doglike Tasmanian wolf. Early kangaroos developed a plant-eating way of life similar to that of hoofed placentals.

Both marsupials and placental mammals spread to South America during the Cretaceous Period. But at the end of that period, South America became separated from the rest of the world for about 60 million years. As a result, many unique kinds of mammals developed on that continent. Prehistoric South American marsupials included the Thylacosmilus << `thy` luh koh SMY luhs >>, a predator that looked like a saber-toothed cat, and Borhyaena << bor hy EE nuh >>, which resembled a wolf. Placental mammals in South America included armadillos and huge ground sloths.

About 3 million to 4 million years ago, a land connection formed between North and South America. Many North American mammals moved to South America, causing the extinction of numerous South American marsupials and placentals. But some South American mammals migrated in the opposite direction and settled in North America. These included the opossum, a marsupial, and the porcupine, a placental.

The development of other animals.

All major groups of modern amphibians and reptiles had evolved by the Cretaceous Period and survived the great extinction 66 million years ago. Among reptiles, lizards and snakes became common. Many birds developed during the Cenozoic Era. They included the flightless Diatryma << `dy` uh TRY muh >>, which grew about 7 feet (2 meters) tall.

The ice ages.

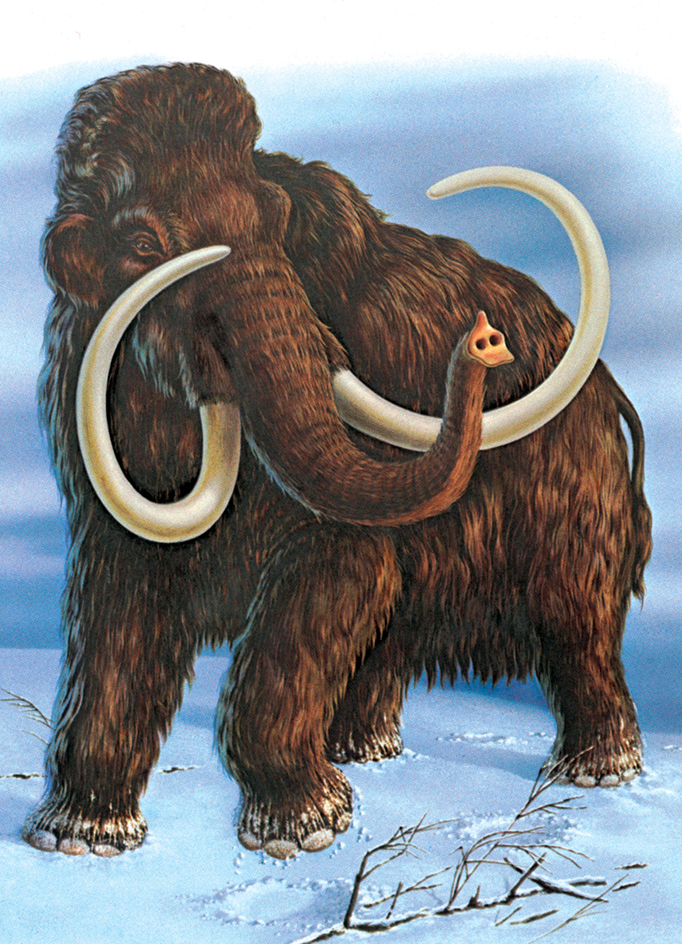

A few million years ago, the climate grew colder on the northern continents. This led to a series of ice ages during the Pleistocene Epoch, which occurred about 2.6 million to 11,500 years ago. During these ice ages, glaciers repeatedly spread and retreated over large areas of North America, Europe, and Asia. One of the most prominent mammals of this period, the elephantlike mammoth, roamed the frozen plains of the Northern Hemisphere. Its thick coat of dense, long hair helped keep it warm.

Many large placental mammals died out before the last glaciers retreated about 11,500 years ago. In North America, these included giant ground sloths, saber-toothed cats, and mammoths. Some scientists believe many large mammals were hunted to extinction by prehistoric people, but others argue that the animals disappeared because of changes in climate and plant life.

Prehistoric human beings lived only a short part of Earth’s long history. Fossil evidence shows that prehistoric people evolved from humanlike apes between about 10 million and 5 million years ago.

The study of prehistoric animals

Interpreting fossil evidence.

Fossils provide paleontologists with a record of prehistoric animals and plants and the environments in which they lived. On rare occasions, entire prehistoric creatures are preserved as fossils. Most fossils, however, consist of such hard body parts as shells, bones, and teeth.

Paleontologists must compare fossils with animals that live today to learn about prehistoric creatures. Scientists can estimate an ancient mammal’s size and weight by comparing the shape and size of its leg bones with leg bones of related modern mammals. Fossils also reveal information about an animal’s way of life. Prehistoric animals with long legs probably were fast runners, just like animals with long legs today, whereas animals with short, stout legs moved more slowly. By measuring the distance between a dinosaur’s fossilized footprints, paleontologists can calculate how fast the animal moved. The shape of fossil teeth can show what type of food a prehistoric animal ate. The teeth of meat-eaters have sharp edges for cutting and slicing through meat, while plant-eaters often have broad, blunt teeth for grinding plant material, which may include tough fibers.

Fossils show that many prehistoric animals have descendants that still exist today. Birds are living descendants of dinosaurs called theropods. Bird skeletons resemble the skeletons of meat-eating dinosaurs more closely than they resemble those of any living animal.

Evolution and extinction.

According to the theory of evolution, organisms adapt to changes in their environment by developing new characteristics. These characteristics increase their chance to survive and flourish under the changed conditions. The study of fossils provides important evidence for evolution. Fossils show that living beings usually have developed from simpler organisms throughout Earth’s long history.

Much evolutionary change is gradual, producing a kind of extinction called background extinction. In background extinction, old species slowly die out as new ones evolve. But during a mass extinction, many different kinds of plants and animals suddenly die out. One of the best-known extinctions occurred at the end of the Cretaceous Period, when dinosaurs and many other living things died off.

Some paleontologists think a collision of an asteroid with Earth caused each mass extinction. But according to other scientists, this theory may not explain why many animals survived such events. They think an overall change in Earth’s climate caused most large extinctions. A general rise or fall in temperature or a change in the amount of rainfall could create conditions in which some species die off and others adapt and survive. Extinctions may also result after animals move across a newly formed land bridge into a new area. The newcomers may compete successfully for food with animals already living there, thus killing off the native species. See Extinction.

By studying why prehistoric extinctions occur, scientists may learn more about why species are disappearing today. Up to 99.9 percent of all animal species that have ever existed are now extinct.