President of the United States is often considered the most powerful elected official in the world. The president leads a nation of great wealth and military strength. Presidents have often provided decisive leadership in times of crisis, and they have shaped many important events in history.

The Constitution of the United States gives the president enormous power. However, it also limits that power. The authors of the Constitution wanted a strong leader as president, but they did not want an all-powerful king. As a result, they divided the powers of the United States government among three branches—executive, legislative, and judicial. The president, who is often called the chief executive, heads the executive branch. Congress represents the legislative branch. The Supreme Court of the United States and other federal courts make up the judicial branch. Congress and the Supreme Court may prevent or end any presidential action that exceeds the limits of the president’s powers and trespasses on their authority.

The president has many roles and performs many duties. As chief executive, the president makes sure that federal laws are enforced. As commander in chief of the nation’s armed forces, the president is responsible for national defense. As foreign policy director, the president determines United States relations with other nations. As legislative leader, the president recommends laws and works to win their passage. As head of a political party, the president helps mold the party’s positions on national and foreign issues. As popular leader, the president tries to inspire the people of the United States to work together to meet the nation’s goals. Finally, as chief of state, the president performs a variety of ceremonial duties.

A number of presidents became great leaders. The most admired ones include George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy. These leaders served as president when the United States faced extraordinary challenges. They also met those challenges with courage, determination, energy, imagination, and political know-how. Some of the most admired presidents at times asserted their own power to interpret the U.S. Constitution or showed little regard for Congress. When their actions won public support, they broadened respect for the presidency and strengthened the office.

The presidency

Legal qualifications.

The Constitution establishes only three qualifications for a president. A president must (1) be at least 35 years old, (2) have lived in the United States at least 14 years, and (3) be a natural-born citizen.

Courts have never decided whether a person born abroad to American parents could serve as president of the United States. However, many scholars believe that such a person would be considered a natural-born citizen.

Term of office.

The president is elected to a four-year term. The 22nd Amendment to the Constitution provides that no one may be elected president more than twice. Nobody who has served as president for more than two years of someone else’s term may be elected more than once.

Before the 22nd Amendment was approved in 1951, a president could serve an unlimited number of terms. Franklin D. Roosevelt held office longest. He was elected four times and served from March 1933 until his death in April 1945. President William H. Harrison served the shortest time in office. He died a month after his inauguration in 1841.

The Constitution allows Congress to remove a president from office. The president first must be impeached (charged with wrongdoing) by a majority vote of the House of Representatives. Then, the Senate, with the chief justice of the United States serving as presiding officer, tries the president on the charges. Removal from office requires conviction by a two-thirds vote of the Senate.

Only three presidents—Andrew Johnson, Bill Clinton, and Donald J. Trump—have been impeached. Johnson and Clinton both remained in office, however, because the Senate failed to convict them. Trump, who was impeached twice, was acquitted by the Senate in 2020 and remained in office. He was acquitted a second time in 2021, weeks after he left office. Congress also considered articles of impeachment against Richard Nixon. After those articles were approved by the House Judiciary Committee, Nixon resigned from office.

Salary and other allowances.

The president receives a salary of $400,000 a year. The chief executive also gets $50,000 annually for expenses, plus allowances for staff, travel, and maintenance of the White House. Congress establishes all these amounts.

After leaving office, a president qualifies for a basic pension. Beginning in 2024, the basic amount for retired presidents is $246,400 yearly. But a number of factors may affect the actual size of the pension. For example, it will be larger if the president has served in Congress. Other retirement benefits include allowances for office space, staff, and mailing expenses. Widowed spouses of former presidents may receive an annual pension of $20,000.

Roads to the White House

The chief road to the White House is the presidential election held every four years. However, a person may become president of the United States in several other ways as well.

The presidential election.

The Constitution requires that presidential elections be held every four years. Most top presidential candidates must first compete against fellow political party members to win the party’s presidential nomination. The Democratic and Republican parties are the two main political parties in the United States. Both parties hold presidential primaries or caucuses in the first half of the election year to select their candidates. Each party then holds a national convention to nominate its presidential candidate. The conventions take place a few months before the presidential election.

The Democratic and Republican conventions are lively spectacles. Millions of Americans watch them on television. Delegates wave banners and cheer wildly to support their choice for president. See Political convention.

After the conventions, the presidential nominees campaign across the nation. Candidates for president face many challenges. They must raise millions of dollars for campaign expenses, attract many volunteers, and gain the support of voters throughout the country. The campaign continues until Election Day, the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

On Election Day, voters in each state and the District of Columbia mark a ballot for president and vice president. This balloting is called the popular vote. The popular vote does not directly decide the winner of the election. Instead, it determines the delegates who will represent each state and the District of Columbia in the Electoral College. These delegates officially elect the president and vice president.

The Electoral College has 538 delegates, each of whom casts one electoral vote. To be elected president, a candidate must win a majority, or 270, of the electoral votes. Each state has as many electoral votes as the total of its representatives and senators in Congress. The District of Columbia has three electoral votes.

The Electoral College voting takes place in the December following the presidential election. The results are announced in January, but the public usually finds out who the president will be a few hours after polls close on Election Day. This is because the popular vote in each state determines which candidate will win that state’s electoral votes. In most states, the candidate who gets the most popular votes in a state will receive by custom or law all the state’s electoral votes. In two states, Maine and Nebraska, the candidate who wins each congressional district receives the electoral vote for that district. Thus, the press can forecast the winner.

The winner of the nationwide popular vote nearly always receives a majority of the electoral votes and becomes president. But the Electoral College has elected four presidents who lost the popular vote. These presidents were Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, Benjamin Harrison in 1888, George W. Bush in 2000, and Donald J. Trump in 2016. A fifth president, John Quincy Adams, lost the popular vote in the election of 1824. However, Adams was elected president by the House of Representatives after no candidate had received a majority of the electoral votes. Ronald Reagan received the greatest number of electoral votes of any president—525 in 1984. See Electoral College.

The inauguration

is the ceremony of installing the new or reelected president in office. It is held at noon on January 20 after the election. Hundreds of thousands of spectators attend the inauguration, which usually takes place outside the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. Millions of other Americans see the event on television.

The highlight of the inauguration ceremony occurs when the new president takes the oath of office from the chief justice of the United States. With right hand raised and left hand on an open Bible, the new president says: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Loading the player...

Presidential oath of office

Other roads to the White House.

A person may become president in other ways besides winning the presidential election. These procedures are established by Article II of the Constitution; the 12th and 20th amendments; and the Presidential Succession Act.

Article II provides that the vice president becomes president whenever the president dies, resigns, is removed from office, or cannot fulfill the duties of the presidency. Nine vice presidents became president by filling a vacancy. One of them, Gerald R. Ford, followed an unusual route to the White House. President Richard M. Nixon nominated him to succeed Spiro T. Agnew, who had resigned as vice president in 1973. In 1974, Nixon resigned as president, and Ford succeeded him. Ford was the only president who was not elected to either the vice presidency or the presidency.

The 12th Amendment permits Congress to act if no candidate for president wins a majority of the electoral votes. Then, the House of Representatives chooses the president. Each state delegation casts one vote.

The House has elected two presidents, Thomas Jefferson in 1801 and John Quincy Adams in 1825. Originally under the Constitution, each elector simply voted for two candidates. The candidate with the most votes became president and the candidate with the next highest number became vice president. In 1800, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr—intended by their party as its candidates for president and vice president—tied in the vote count, sending the election to the House of Representatives. The 12th Amendment, ratified in 1804, said electors were to vote for one person as president and another as vice president.

In 2000, the presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore was so close that it was virtually tied. However, the House of Representatives did not choose the winning candidate. Bush had won the state of Florida by fewer than 1,800 votes, and Gore requested a court-ordered recount of the votes. In the case of Bush v. Gore, the U.S. Supreme Court stopped the recount. That court ruling established Bush as the winner of the election.

The 20th Amendment states that if the Electoral College chooses a president elect who then dies before the inauguration, the vice president elect becomes president. If a presidential candidate dies before the Electoral College meets, leaders of the candidate’s party may select a new presidential candidate for their party. The college would then vote on that selection. The 20th Amendment also changed the date for the start of Congressional sessions to January 3. This provision ensured that should the choice of president fall to Congress, the newly elected Congress makes the selection. Neither of these provisions has ever been applied.

The Presidential Succession Act permits other high government officials to become president if vacancies exist in both the presidency and the vice presidency. Next in line is the speaker of the House. Then comes the president pro tempore (temporary president) of the Senate, usually the majority party member who has served the longest in the Senate. Next are members of the important presidential advisory group that is known as the Cabinet, with the secretary of state first. The Succession Act has never been applied. See Presidential succession.

The executive branch

The president heads the executive branch of the federal government. This branch includes the Executive Office of the President, created by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939. The executive branch also includes 15 executive departments and about 80 independent agencies that were created by Congress.

The Executive Office of the President

includes a number of agencies that work directly for the chief executive. One of them, the White House Office, includes the president’s physician, secretaries, and a number of close, influential aides known as presidential assistants (see Presidential assistant). The White House Office also includes such agencies as the Domestic Policy Council and the National Economic Council.

Other Executive Office agencies also provide ideas and suggestions concerning many national and international issues. These agencies include the Council of Economic Advisers, Council on Environmental Quality, National Security Council, National Space Council, Office of Management and Budget, Office of the National Cyber Director, Office of National Drug Control Policy, Office of Science and Technology Policy, and Office of the United States Trade Representative.

The executive departments

directly administer the federal government. They are the departments of (1) State, (2) the Treasury, (3) Defense, (4) Justice, (5) the Interior, (6) Agriculture, (7) Commerce, (8) Labor, (9) Health and Human Services, (10) Housing and Urban Development, (11) Transportation, (12) Energy, (13) Education, (14) Veterans Affairs, and (15) Homeland Security.

The heads of all but one of the executive departments are called secretaries. The head of the Justice Department is the attorney general. The department heads belong to the president’s Cabinet. The president nominates the department heads. All the appointments require approval of the Senate.

The independent agencies

, which administer federal programs in many fields, are also part of the executive branch. These agencies oversee programs in such fields as aeronautics and space, banking, communications, farm credit, labor relations, nuclear energy, securities, small business, social security, and trade. Agencies are considered to be independent when Congress limits the president’s authority over the agency. Although the president nominates the heads of independent agencies, subject to Senate approval, Congress may limit the president’s power to remove the head of these agencies.

Independent agencies may issue rules, enforce penalties, and administer programs that have far-reaching effects on American life. Some independent agencies are known as regulatory agencies. Important regulatory agencies include the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Communications Commission, and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Roles of the president

The only roles that the Constitution clearly assigns to the president are those of chief administrator of the nation and commander of its armed forces. But court decisions, customs, laws, and other developments have greatly expanded the president’s responsibilities and powers. Today, the president has seven basic roles: (1) chief executive, (2) commander in chief, (3) foreign policy director, (4) legislative leader, (5) party head, (6) popular leader, and (7) chief of state. Because the Constitution’s description of the executive power is open-ended, the extent of that power is often contested. The president has the most power when Congress agrees with the president’s use of that power, and the least power when the president acts against the will of Congress.

Chief executive.

As chief executive, the president has four main duties. They are (1) to enforce federal laws, treaties, and federal court rulings; (2) to develop federal policies; (3) to prepare the national budget; and (4) to appoint federal officials.

The president is required to enforce the laws enacted by Congress. Congress can enact laws to give the president emergency powers—that is, special authority to prevent or end a national emergency. For example, the Taft-Hartley Act allows the president to delay a labor strike for 80 days if it might endanger “national health or safety.” The president also may issue executive orders. Executive orders are directions, proclamations, or other statements that may have the force of laws. One of the most famous executive orders was the Emancipation Proclamation issued by Abraham Lincoln in 1863, during the American Civil War. It declared freedom for all slaves in the areas then under Confederate control.

Every year, the president presents a budget to Congress. Presidents often use their budgets to shape key programs. Lyndon B. Johnson did so in the mid-1960’s to develop his War on Poverty program.

The president nominates Cabinet members, Supreme Court justices, and other high federal officials. All such top appointments require Senate approval. The president can appoint a number of personal aides and advisers and can fill hundreds of lower jobs in the executive branch without Senate approval.

The Constitution also allows the president to issue reprieves and pardons for crimes against the United States, except in impeachment cases. A reprieve delays the penalty for a crime. A pardon frees the offender from a sentence or the possibility of a sentence.

Commander in chief.

The president’s main duties as commander of the nation’s armed services are to defend the country during wartime and to keep it strong during peacetime. The chief executive appoints all the nation’s highest military officers and helps determine the size of the armed forces. Only the president can decide whether to use nuclear weapons. It remains unclear how much power the president has to send troops to other countries without congressional authorization.

The president shares some military powers with Congress. Top appointments in the armed services require congressional approval. Major military expenses and plans to expand the armed forces also need the consent of Congress. Only Congress can declare war. However, Congress has not declared war since the United States entered World War II in 1941. Nonetheless, presidents have repeatedly sent American troops into conflicts that were equal to war though none was declared. In 1950, for example, Harry S. Truman ordered U.S. troops to fight in South Korea. The Korean War (1950-1953) and Vietnam War (in which U.S. forces became involved in the 1960’s) were officially only “police actions.” In 1973, Congress enacted a law that restricts the president’s authority to keep U.S. troops in a hostile area without Congress’s consent. The law reasserted Congress’s role in foreign affairs but has had mixed success in curbing the president’s warmaking authority. In one example of its use, President George H. W. Bush asked for congressional approval before sending troops into Iraq and Kuwait in 1991.

Congress generally allows the president to exercise broad powers in wartime. During World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt created many emergency agencies, took control of American manufacturing plants, and even imprisoned American citizens of Japanese descent. After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States, Congress gave broad authority to the president to combat terrorism at home and abroad.

Foreign policy director.

The Constitution gives the president power to appoint ambassadors, make treaties, and receive foreign diplomats. The chief executive may refuse to recognize a newly formed foreign government. The president also proposes legislation dealing with foreign aid and other international activities.

Treaties and ambassadorial appointments require approval of the Senate. The president may also make executive agreements with foreign leaders. These agreements resemble treaties but do not need Senate approval.

Some presidents have helped settle disputes between foreign nations. Theodore Roosevelt and Wilson were among the first presidents to serve as peacemakers in foreign conflicts. Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace Prize for helping end the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). Wilson helped work out the peace treaty that ended World War I (1914-1918). Jimmy Carter hosted the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt in 1978. In 1998, Bill Clinton facilitated the Good Friday Agreement between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland.

Legislative leader.

The president greatly influences the development of many laws passed by Congress. At the beginning of each session of Congress, the chief executive delivers a State of the Union address to the lawmakers. In this message, the president discusses the major problems facing the nation and recommends a legislative program to solve them. The president also gives Congress detailed plans for new legislation at other times during the year.

Cabinet officers and other presidential aides work to win congressional support for the president’s programs. However, the president also may become involved in a struggle over a key bill. In such cases, the president may speak to members of Congress several times to win their backing. This activity requires shrewd bargaining and in many cases fails in spite of the president’s influence.

When signing an act passed by Congress into law, the president may issue a presidential signing statement that reflects the president’s views on the law. Signing statements may influence how government agencies apply and enforce laws, or how courts interpret laws. During the early 2000’s, the use of signing statements generated controversy among constitutional law experts. Supporters of the practice claimed that presidents have the authority to dispute parts of laws passed by Congress. Critics, however, argued that such use of signing statements weakens the constitutional system of checks and balances, and that presidents should instead veto any bill they believe is unconstitutional.

The president has the authority to veto any bill passed by Congress. If both the House and the Senate repass the vetoed bill by a two-thirds majority, the bill becomes law despite the president’s disapproval. Congress has overturned only a small percentage of all vetoes.

Party head.

As leader of a political party, the president helps form the party’s positions on all important issues. The president hopes these positions will help elect enough party members to Congress to give the party a majority in both the House and the Senate. Such a strong party makes it easier to pass the president’s legislative program.

However, presidents cannot always control members of their party in Congress. Senators and representatives owe their chief loyalty to the people in their state and local district. They may vote against a bill favored by the president if it meets with opposition at home.

Presidents try to win the support of legislators in several ways. They often use patronage power, the authority to make appointments to government jobs. For example, a president can reward a loyal supporter by approving that person’s choice for a federal judge. A president also may campaign for the reelection of a faithful party member or promise to approve a federal project that will benefit a legislator’s home district.

Popular leader.

The president and the American people have a special relationship. The people rely on the chief executive to serve the interests of the entire nation ahead of those of any state or citizen. In turn, the president depends on public support to help push programs through Congress. The president seeks such support by explaining the issues and by showing the confidence and determination to deal with problems.

The president uses many methods to communicate with the public and provide strong national leadership. Woodrow Wilson pioneered the use of regular presidential press conferences to mold public opinion and to rally support. Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed the nation over radio in his “fireside chats.” He was also the first president to speak on television. Since the 1960’s, presidents have favored the use of televised addresses from the White House to reach large audiences. Donald J. Trump used the social media site Twitter (now called X) to reach his supporters directly.

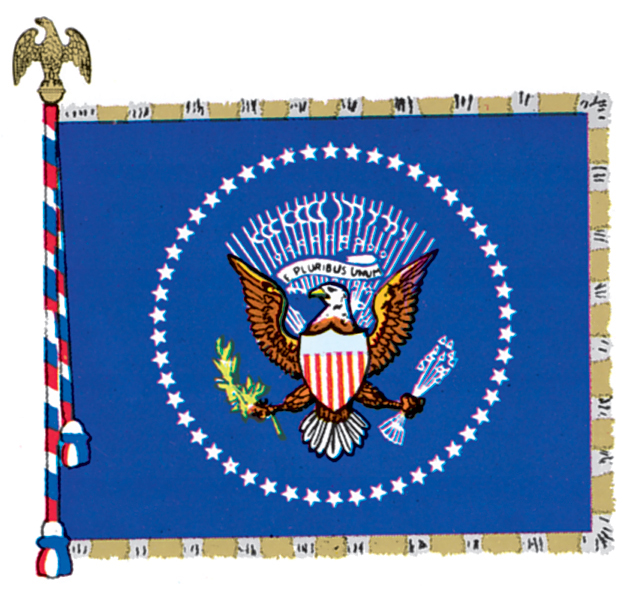

Chief of state.

As the foremost representative of the U.S. government, the president is expected to show pride in American achievements and traditions. In this role, the president attends historical celebrations, dedicates new buildings and national parks, and may throw out the first ball of the professional baseball season. The president also presents awards to war heroes and invites distinguished Americans to the White House.

In addition, the chief executive greets visiting foreign officials and often hosts formal White House dinners for them. The president also represents the United States in visits to other countries.

The life of the president

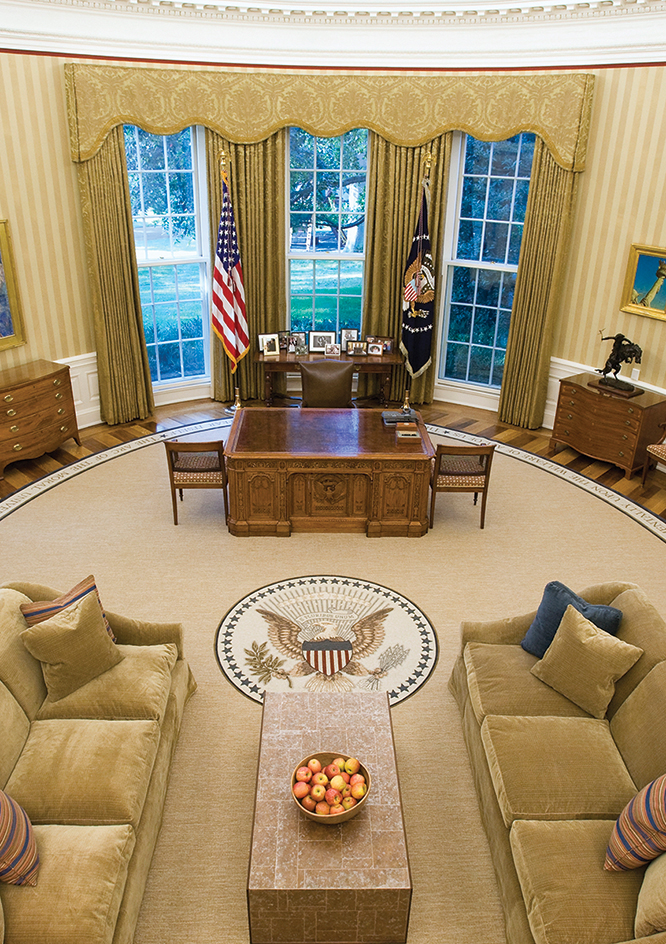

The White House.

The president’s headquarters is the Oval Office, an oval-shaped room in the White House. There, the chief executive meets congressional leaders, foreign officials, and representatives of various groups. The president also spends much time in the Oval Office studying reports from aides and agencies.

The presidential family’s main living quarters are on the second floor of the White House. The family also can relax in the mansion’s swimming pool and at its bowling lanes and motion-picture theater. The White House grounds have some beautiful gardens.

In spite of its beauty and comfort, however, the White House lacks privacy. Every week, thousands of visitors tour the rooms that are open to the public. Partly as a result, most presidents enjoy recreation outside the White House.

The president’s family

generally attracts wide interest. The wedding of a president’s child is a major news event. An interesting relative also draws much attention. Even unimportant activities of members of the president’s family sometimes appear in the newspapers.

Guarding the president.

The United States Secret Service guards the president at all times. In addition, agents of the Secret Service continually check the president’s food, surroundings, and travel arrangements.

At various times, the president travels in an official car, a private airplane, or a U.S. Navy ship. The chief executive usually flies long distances in a reserved jet called Air Force One.

Even though U.S. presidents get tight protection, four have been assassinated while in office. They were Abraham Lincoln in 1865, James Garfield in 1881, William McKinley in 1901, and John F. Kennedy in 1963. Others have survived attempted assassinations, including Harry S. Truman, Gerald R. Ford, and Ronald Reagan.

Development of the presidency

The founding of the presidency.

During and immediately after the American Revolution (1775-1783), the government of the United States operated under laws called the Articles of Confederation. The Articles gave the national government little authority over the states. Most Americans agreed that the nation needed to strengthen its federal government. In 1787, a group of state leaders gathered in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation. Instead, they wrote an entirely new document—the Constitution of the United States.

Under the Articles, the chief officer presiding over Congress had been called the president, and that title was chosen for the leader of the new government. The authors of the Constitution described the presidency in fairly general language because they knew that the nation’s respected wartime leader, George Washington, would be the first president. They expected Washington to shape the responsibilities of the office for future presidents. Loading the player...

Washington, the first President of the United States of America

Washington brought extraordinary courage, prestige, and wisdom to the U.S. presidency. In 1793, he kept the young nation out of a war between the United Kingdom and France. In 1794, Washington used federal troops to put an end to the Whiskey Rebellion, a tax protest in the state of Pennsylvania. This action helped establish the federal government’s authority to enforce federal laws in the states.

Strengthening the office.

During the early and mid-1800’s, the nation had several bold and imaginative presidents. These leaders interpreted the Constitution in new ways and greatly increased the power of the presidency. One of these leaders was Thomas Jefferson, the third president.

Jefferson raised a constitutional question when he approved a treaty to buy the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803. The purchase almost doubled what was then the area of the United States. The Constitution did not specifically give the president power to buy new territory. But Jefferson decided that the purchase was constitutional under his treaty-making power.

Andrew Jackson strengthened the president’s role as the nation’s popular leader. In July 1832, Jackson vetoed a bill to renew the charter of the Second Bank of the United States. Jackson and many other Americans viewed the bank as a dangerous monopoly and criticized its failure to establish a reliable currency. Later in 1832, South Carolina declared federal tariff laws unconstitutional and refused to collect tariffs at its ports. Jackson declared that no state could cancel a federal law. The president received congressional approval to use federal troops in order to collect the tariffs. Jackson’s actions helped force South Carolina to end its rebellion.

The American Civil War began in 1861, when Southern forces attacked Fort Sumter. Abraham Lincoln ordered a military draft, blockaded Southern ports, and spent funds without congressional approval. He knew he had used powers the Constitution reserved for Congress. But he believed his actions were needed to save the Union. When Congress reconvened, Lincoln asked for, and received, congressional approval of his actions. Throughout the war, Lincoln continued to assert strong presidential powers. For example, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation and orders requiring military trials of Confederate sympathizers.

The decline of the presidency.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Congress moved quickly to increase its influence in the government. A power struggle broke out between Congress and Andrew Johnson. This struggle led to Johnson’s impeachment by the House of Representatives. The prestige of the presidency was damaged, but it was saved from total destruction because the Senate failed, by one vote, to convict Johnson.

Few strong presidents emerged during the late 1800’s. Most presidents of the period accepted the view that Congress, not the chief executive, had the responsibility to set the nation’s basic policies.

The rebirth of presidential leadership.

The United States became a world power during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. This development helped bring increased power to the president. In the Spanish-American War (1898), the United States took control of Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. To protect these interests, Theodore Roosevelt built up U.S. military forces. He also warned European nations against interfering in Latin America. Roosevelt broadened the scope of executive power at home by leading a fight for reforms that limited the power of great corporations.

Woodrow Wilson enlarged the presidency during World War I (1914-1918). After the United States entered the conflict in 1917, Wilson rallied public support for the war effort. He won widespread praise for his pledge to help make the world safe for democracy. After the war, Wilson led the drive to establish the League of Nations, an international organization dedicated to maintaining peace.

Perhaps no one expanded the powers of the presidency as much as Franklin D. Roosevelt. He became president during the Great Depression of the 1930’s and took extraordinary measures to combat the severe business slump. Roosevelt won public acceptance of his view that the federal government should play a major role in the economy. Largely as a result of strong popular support, he convinced Congress to adopt a far-reaching program called the New Deal. This program created work for millions of Americans and strengthened the president’s role as the nation’s legislative leader.

The rapid growth of U.S. military strength during World War II (1939-1945) further increased the influence of the presidency in world affairs. Harry S. Truman’s decision to use atomic bombs against Japan during the war showed the tremendous authority of the president.

Another example of this authority occurred in the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. In that crisis, John F. Kennedy carried out negotiations that resulted in the withdrawal of Soviet missiles from Communist Cuba. The Soviet Union had placed nuclear missiles in Cuba capable of striking U.S. cities. Kennedy demanded the missiles’ removal and announced a naval blockade of Cuba. Several days later, the Soviets withdrew their missiles after the United States publicly promised to withdraw its nuclear missiles from Turkey and privately agreed not to invade Cuba.

The modern presidency.

The presidency lost much of its prestige during the Vietnam War (1957-1975). Lyndon B. Johnson, who became president in 1963, believed that non-Communist South Vietnam had to be defended against local Communist rebels and Communist North Vietnam. In 1964, Congress allowed him “to take all necessary measures” to protect U.S. bases in South Vietnam.

During the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, Johnson and his successor, Richard M. Nixon, sent hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops to support South Vietnam. Many Americans opposed United States participation in the Vietnam War. They argued that both Johnson and Nixon had abused presidential powers and misled Congress.

The Watergate scandal further damaged public regard for the presidency. It involved burglary, wiretapping, and other illegal activities designed to help Nixon win reelection in 1972. Attempts by White House aides to cover up many of those activities led to an investigation by the House of Representatives. In July 1974, the House Judiciary Committee recommended that Nixon be impeached.

That same month, Nixon lost an appeal to the Supreme Court involving the president’s executive privilege—the right to keep records secret. In United States v. Nixon, the court ruled that executive privilege is not unlimited. It ordered Nixon to release recordings of White House conversations said to contain evidence for a criminal case in the Watergate scandal. By then, Nixon had lost nearly all his support in Congress and faced possible impeachment. He resigned as president on Aug. 9, 1974, and was succeeded by Vice President Gerald R. Ford. Nixon was the only president ever to resign.

Many Americans thought Nixon had violated federal laws and wanted him brought to trial. The nation became further divided in September 1974, when Ford pardoned Nixon for all federal crimes Nixon may have committed as president.

In 1998, the House impeached Bill Clinton for perjury and obstruction of justice. The House charged Clinton with lying to a grand jury that was investigating an extramarital affair he had while in office. Other charges included hindering the investigation by lying to his aides and by encouraging others to lie and conceal evidence on his behalf. The Senate acquitted Clinton in 1999.

In late 2019, the House voted to impeach Donald J. Trump. The House charged Trump with abuse of power, for urging a foreign power to investigate a domestic political rival, and with obstruction of Congress, for blocking witnesses from speaking to congressional investigators. The Senate acquitted Trump in early 2020. In January 2021, the House impeached Trump for a second time. Representatives approved a single article of impeachment—incitement of insurrection—for “inciting violence against the government of the United States.” On January 6, a violent pro-Trump mob had stormed the U.S. Capitol after Trump delivered a speech accusing opponents of fraud in the 2020 election. The Senate acquitted Trump again in February 2021, weeks after he had left office.

The presidency today

is still strong and important. This is largely because the United States has powerful armed forces and ranks as a leader of the democracies. In addition, the president’s ability to reach huge audiences on television and through social media adds to the prestige of the office.

Americans look to the president to build morale, recruit talented officials, and explain complex issues. They also expect the chief executive to champion the rights of all Americans regardless of their age, color, political party, religion, region, or sex. At the same time, some Americans dislike the great size and power of the national government and want the president to reduce federal influence over state and local affairs.

Congress and the Supreme Court sometimes act to prohibit or limit actions that they consider a misuse of presidential power. But such challenges have halted the expansion of presidential authority only for limited periods. The presidency will continue to have its ups and downs. However, it will remain, as John F. Kennedy once said, “the vital center of action in our whole scheme of government.”