Protestantism is the general name for hundreds of Christian denominations (religious groups) that differ slightly or greatly from one another. About 600 million people—approximately 6 percent of the world’s population—are Protestants. Among Christian churches, only the Roman Catholic Church has more members.

Protestantism resulted chiefly from the Reformation, a religious and political movement that began in Europe in the early 1500’s. The word Protestant comes from the Latin word protestans, which means one who protests. It was first used in 1529 at a diet (formal assembly) in Speyer, Germany. At the diet, several German leaders protested an attempt by Roman Catholics to limit the practice of Lutheranism, an early Protestant movement. The leaders became known as Protestants. The name soon came to include all Western Christians separated from the Roman Catholic Church.

Since the 1500’s, most Protestants have lived in Europe and North America. However, the number of Protestants in Africa, Asia, and Latin America has grown considerably since the late 1900’s.

Protestant beliefs

Protestant churches share most Christian beliefs with the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. For example, Protestants believe there is only one God. Most Protestants also believe that in God there are three Divine Persons who together form the Trinity (see Trinity ). These Persons are the Father; the Son, who is Jesus Christ; and the Holy Spirit. Protestants also believe in the central importance of Jesus as the savior of humanity.

Historically, Protestants have disagreed most with other Christians over the ways in which human beings relate to God. As a result of this disagreement, Protestants have developed distinctive beliefs in certain areas. Two prominent beliefs involve (1) the nature of faith in God and the grace of God and (2) the authority of the Bible.

Faith and grace.

Protestants oppose the Catholic doctrine of salvation. Catholics teach that people are saved when God infuses (fills) them with his grace, enabling them to believe in him and do good works. In this process, people freely cooperate with God. Protestants, by contrast, emphasize that God saves people entirely by his grace, without any cooperation or works on their part. This teaching is called justification by grace alone or justification by grace through faith.

According to Protestantism, God is first of all gracious—that is, he is loving and forgiving. God establishes and is responsible for his relationship with people. Protestants believe people are incapable of saving themselves because of their sins. Therefore, they must be saved by God’s grace and not by their own striving or merit. Protestants believe God’s grace comes to people through Jesus Christ. They regard Jesus’s Crucifixion as a saving act of God’s love and justice. For them, faith means being moved by the Holy Spirit to trust in the saving power of God in Jesus. Protestants believe that such faith makes it possible to live free from sin and to serve others. Thus, people receive salvation by having faith in God’s graciousness, which comes to them through Jesus.

The authority of the Bible.

Roman Catholic beliefs are based on the Bible and church traditions. These traditions include creeds (condensed expressions of faith) and dogmas (formal teachings) formulated by church councils and popes, as well as historic patterns of worship and church order. Protestants, on the other hand, reject the idea that church traditions should have religious authority higher than or equal to the Bible’s. Most Protestants believe that while traditions are important, the Bible should serve as the final religious authority.

In the course of Protestant history, several denominations have based their beliefs on other authorities in addition to the Bible. For example, some churches believe that personal religious experience or divinely inspired leadership may serve to direct their faith. Others believe they must test their faith against reason or firmly uphold certain church traditions. In general, however, the Bible remains the central religious authority for Protestants.

Worship

Protestants commonly worship the Triune God, made up of three Divine Persons, of the Christian gospels. But various denominations worship God in different ways. Protestant liturgies (worship services) range from the simple, informal meetings of the Quakers to the ecstatic singing and preaching of Christians known as charismatics and the elaborate ceremonies of some Anglican churches. Despite many differences, most Protestant liturgies share such basic features as (1) the central place of the word of God, (2) the celebration of the sacraments, and (3) an important role for the laity (church members who are not clergy).

The central place of the word of God.

Most Protestant worship stresses the public reading of the Bible and preaching God’s word. Protestants believe God is present in their midst and inspires faith in them when they read from and listen to the Bible and apply its teachings to their lives.

Celebration of the sacraments.

Various Protestant denominations disagree about the nature and number of solemn observances called sacraments. But most denominations include at least two sacraments—baptism and the Lord’s Supper—in their worship.

Baptism is a religious act that signals the beginning of Christian life and inclusion in the community of the church. Some Protestants baptize their infant children. Others baptize only those old enough to declare independently their personal faith. Most Christians connect baptism with God’s gifts of faith and grace.

The Lord’s Supper, or Holy Communion, is a ceremony that reenacts Christ’s words and actions at the Last Supper and recalls his Crucifixion. Protestants believe that by celebrating the Lord’s Supper, they are remembering and participating in Jesus’s sacrifice of his life for the forgiveness of sins. Protestants have debated the way in which Christ is understood to be present in the celebration of the Lord’s Supper.

The laity

has an important role in most Protestant worship. Lay people are expected to participate in the liturgy through song and prayer. They often are urged to take leading roles in the liturgy, and even to preach.

History

Most Protestant denominations originated during the Reformation in Europe. But some, such as the Moravian Church, had begun to take shape earlier. The Reformation itself began in 1517, when Martin Luther, a German monk, protested certain practices of the Roman Catholic Church. By about 1550, Protestantism had spread throughout almost half of Europe. See Reformation .

Protestantism developed as a number of semi-independent religious movements. These movements were alike in their belief in the central importance of faith and the Bible and their rejection of the pope’s authority. But differences of culture, geography, politics, and theology (the study of God) caused them to develop independently in varying degrees. In time, such differences caused the larger movement to split into various denominations.

The resulting Protestant movements can be grouped historically into five general types. These types are (1) the conservative reform movements, (2) the radical reform and free church movements, (3) Pietism, (4) the modern evangelical and Pentecostal movements, and (5) the ecumenical movement.

The conservative reform movements

of the 1500’s included groups that broke away from the Roman Catholic Church but kept many of its basic beliefs and practices. Among such movements, in order of their establishment, were the Lutheran movement; the Reformed, or Presbyterian, movement; and the Anglican, or Episcopalian, movement.

Lutheranism, based on the teachings of Martin Luther, was the earliest major Protestant movement. It spread rapidly throughout northern Germany and the Scandinavian nations during the 1520’s. Lutherans largely agree on the importance of faith and the authority of the Bible. But they have disagreed among themselves over the form of the liturgy and church government. As a result, the Lutherans have split into several smaller groups.

The Reformed, or Presbyterian, movement originated with the teachings of two reformers, Huldreich Zwingli and John Calvin. In the 1520’s, Zwingli, a Swiss priest, urged reforms that were more radical than Luther’s. In the 1530’s, the French reformer John Calvin largely combined the ideas of Luther and Zwingli. Calvin’s teachings strongly influenced people in England, France, the Netherlands, and Scotland. In England, many Reformed Protestants became known as Puritans. In France, they were called Huguenots. The Scottish reformer John Knox introduced Reformed Protestantism into Scotland.

The Anglican, or Episcopalian, movement began in England. It resulted from the Act of Supremacy of 1534, which declared King Henry VIII head of the Church of England. This church became established only after much dispute and bloodshed. In 1559, Queen Elizabeth I established a moderate form of Protestantism that became known as Anglicanism. Many people consider Anglicans to be Protestants. Others regard Anglicanism as a “middle way” between Catholicism and Protestantism.

The radical reform and free church movements.

In the 1500’s, some small Christian groups arose that differed greatly from the Roman Catholic and major Protestant churches. Members of these radical groups thought conservative Protestants had not reformed the Catholic Church enough. Many of the groups rejected conservative reforms and teachings and developed their own communities and forms of worship.

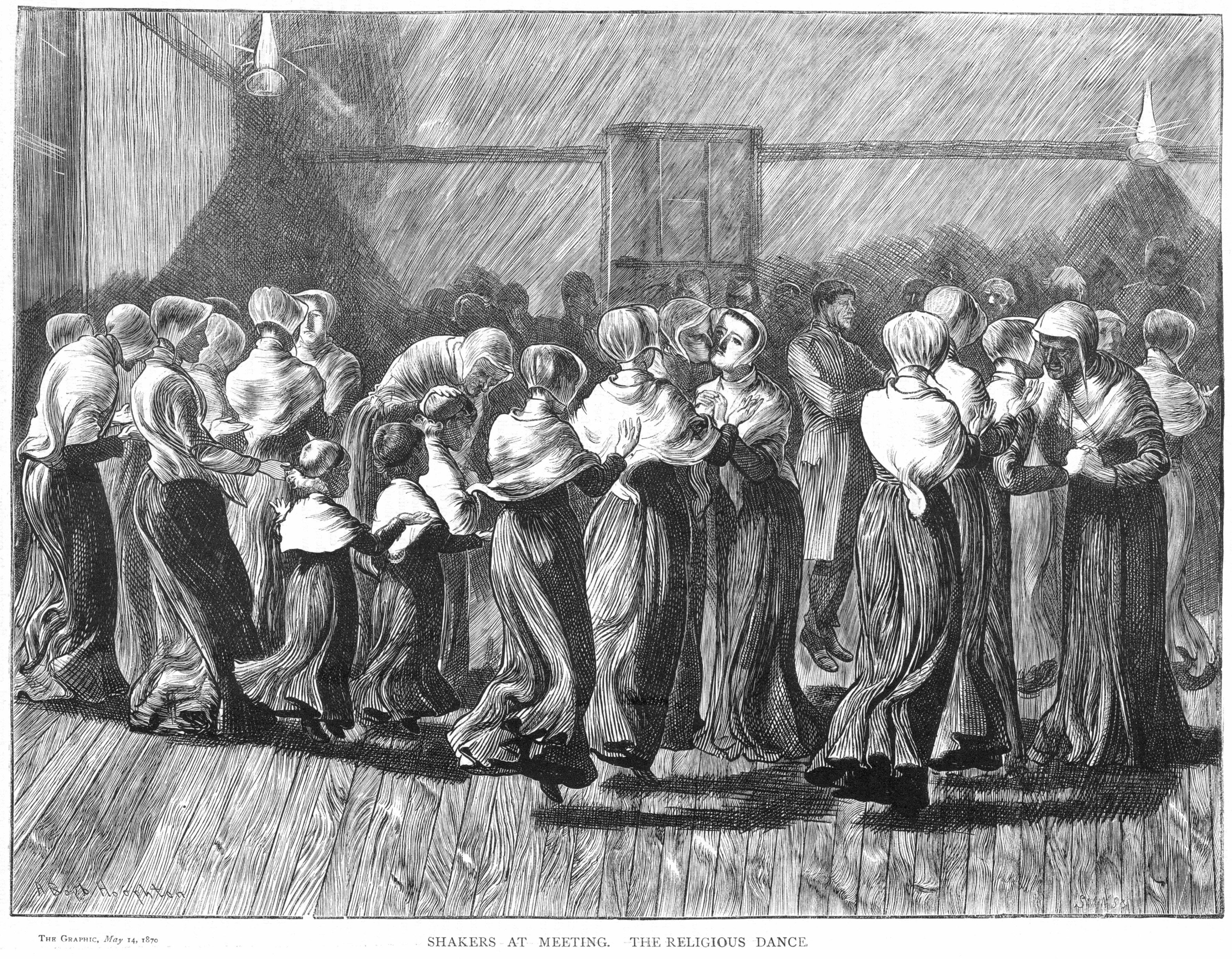

The Anabaptists first appeared in Europe during the Reformation. They received the name anabaptists (rebaptizers) because they baptized adults who joined their communities and who had been baptized in infancy. Other radical groups then developed in Europe and North America over several centuries. They included the Quakers, the Brethren, and the Shakers.

Soon after the Reformation, two radical Protestant groups—the Separatists and the Baptists—arose in England. Their development was related to a reform movement, called Puritanism, within the Church of England. Inspired by John Calvin’s teachings, the Puritans opposed certain policies of the Church of England. Those Puritans who thought they could not reform the church from within separated from it. They were called Separatists or Independents at first. But they soon became known as Congregationalists because of their belief in the rights of local congregations.

In the early 1600’s, an English clergyman named John Smyth led a group of Separatist Christians to the Netherlands. Like the Anabaptists, Smyth’s group believed that only people who were old enough to express their faith should be baptized. They became known as Baptists.

The Congregationalist and Baptist movements, known as free church movements, spread to colonial America. The Pilgrims, a Separatist group led by William Brewster, established the Plymouth Colony in 1620. In 1638, the religious leader Roger Williams founded a Baptist church in Providence in the Rhode Island Colony. By the 1920’s, the Baptist Church ranked as the largest Protestant denomination in the United States.

Pietism

was a religious attitude that developed within European Protestantism during the late 1600’s. Pietists emphasized intense, inward devotion and personal holiness in daily life as the most important expressions of faith. This movement inspired several waves of renewal in European and U.S. Protestant churches in the 1700’s and 1800’s.

The Anglican clergyman John Wesley worked to renew the life of English churches in the early 1700’s. Wesley’s preaching stressed the need for life-changing religious experience and for living a holy life as a result of this experience. In 1744, Wesley organized a missionary movement, holding his first annual conference for lay (unordained) preachers. Protestants who joined Wesley’s movement, which later became a church, were called Methodists. The movement placed importance upon the disciplines or methods of prayer in small groups, Bible study, and preaching. Methodism grew rapidly in England and, later, in North America.

The modern evangelical and Pentecostal movements.

Many Protestant denominations experienced significant revivals and growth under the influence of Pietism. In the 1800’s, Protestants were increasingly inspired to spread their Christian message at home and abroad. They established many missionary societies and enterprises both within and across denominations. By 1900, Protestant churches had spread around the world.

About the same time, intense disputes arose among Protestants about the extent to which faith could agree with modern science. Some Protestants who feared the Bible would lose its authority reasserted this authority in a movement known as fundamentalism. A wide variety of modern Protestant churches commonly known as evangelical churches have many similarities with fundamentalism. They strictly defend Biblical authority and emphasize the importance of life-altering religious experience.

The most conservative and enthusiastic branches of Methodism gave rise to the Holiness Movement, which in turn led to Pentecostalism in the early 1900’s. Pentecostalism places great emphasis on believers’ ecstatic experience of the Holy Spirit, rather than adherence to certain teachings or rituals. It also upholds the Bible as the highest religious authority. Pentecostalism has grown rapidly since the late 1900’s, particularly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. It has also influenced Protestants belonging to other denominations, as well as some Roman Catholics. These people often are called charismatics.

The ecumenical movement.

Since the mid-1800’s, many Protestants have desired to overcome differences between denominations. They have sought to unite various denominations and encourage cooperation through national and international federations (unions) and councils. Many of them also have worked to increase good will, understanding, and missionary collaboration with the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches. This trend toward unity is called the ecumenical movement.

In 1948, church leaders founded the World Council of Churches. This organization continues to work for cooperation and unity among all churches worldwide. In 1965, at an ecumenical (general) council called Vatican Council II, Pope Paul VI expressed the need for unity among all Christians. Many Protestants and other Christians welcomed the pope’s expression of unity and the unifying spirit of the council itself.