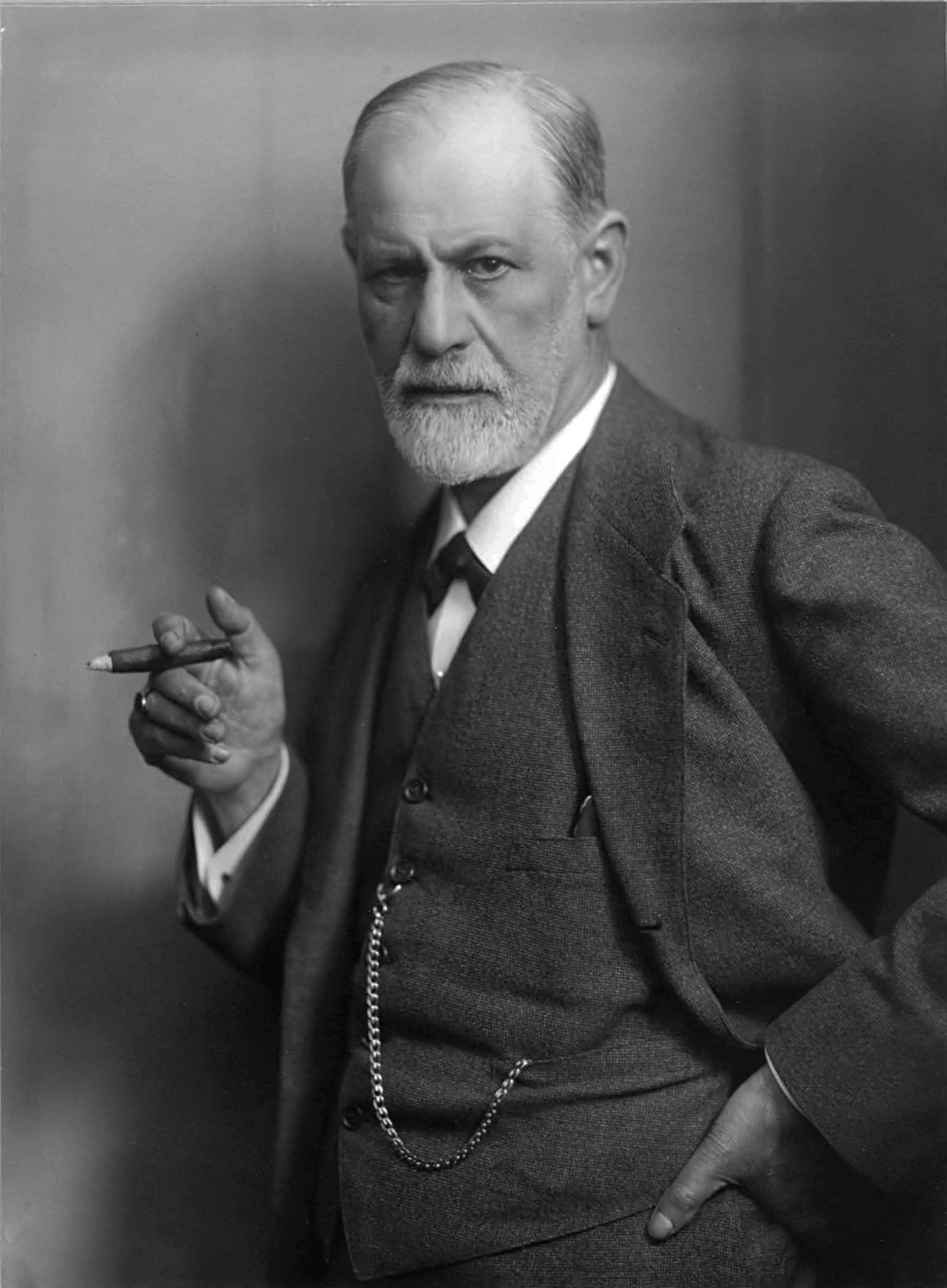

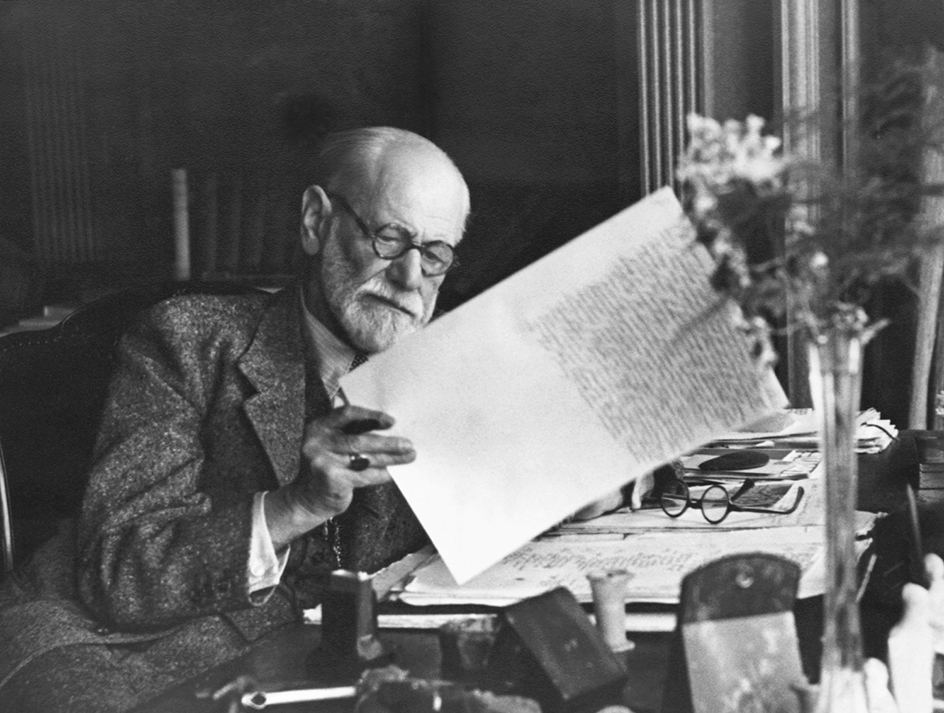

Psychoanalysis << `sy` koh uh NAL uh sihs >> is a method of treating mental illness founded by the Austrian physician Sigmund Freud. Freud developed this treatment during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Other psychiatrists developed variations of his technique. The term psychoanalysis also refers to the theories on which such treatment is based.

According to Freud, a number of mental disorders could be cured by uncovering a patient’s unconscious wishes and fears. He believed that behavior is influenced by instincts, fears, and unconscious mental processes not controlled by rational thought. He claimed that early childhood bodily experiences, including sexual ones, shape an individual’s behavior in later life.

Psychoanalysts believe that unpleasant experiences, especially during childhood, may become buried in the unconscious mind and, together with inborn tendencies, may cause mental illness. Psychoanalytic treatment tries to bring these experiences out of a patient’s unconscious mind and into the conscious mind.

Psychoanalytic treatment

generally lasts for two to five years with sessions three to five times a week. The patient is instructed to reveal all thoughts as they occur. This is called free association. The patient and the analyst attempt to understand the psychological meaning of the ideas, fantasies, dreams, and behaviors that are expressed. During the course of the treatment, patients often transfer strong feelings they have for other people to the therapist. This process is called transference. Transference reveals certain attitudes acquired by patients in early life that have continued to interfere with their relationships with other people. By interpreting this transference, the therapist attempts to help patients achieve greater maturity and freedom in their relationships. Today, variations of psychoanalysis that involve much briefer and less intense treatments are much more commonly practiced.

Psychoanalytic theory.

Freud taught that people do not say or do anything accidentally. Unconscious mental activity causes such “accidents” as slips of the tongue—for example, calling a person by the wrong name without realizing it—or forgetting an appointment. According to Freud, the mind experiences more unconscious than conscious activity.

Freud divided the mind into three parts: (1) the id, (2) the ego, and (3) the superego. Babies are born with an id, a group of instincts within the unconscious. As children grow, they develop an ego and a superego. The ego governs such areas as memory, voluntary movement, and decision making. The superego enables the mind to tell right from wrong. Severe conflicts between two of the parts may cause emotional problems. Difficulties might arise, for example, if the id produces strong desires to do things, but the superego insists that such desires are wrong.

Freud believed that children grow through a series of five overlapping stages of what he called psychosexual development. These stages are (1) the oral phase, (2) the anal phase, (3) the phallic stage, (4) latency, and (5) adolescence. During the oral phase, infants find pleasure in sucking. During the anal phase, which lasts to about age 4, children enjoy controlling the discharge of body wastes. Then, in the phallic stage, they become increasingly aware of their sex organs. They also develop an Oedipus complex, a strong attraction to the parent of the opposite sex. While in elementary school, children move into the less emotional latency period. Adolescence involves a struggle between childish feelings of dependency and adult longings for independence.

Emotional problems during any of the five stages, according to Freud, can cause characteristics of that stage to last into adulthood. A disturbed boy, for example, might remain unconsciously in love with his mother and jealous of his father even as an adult.