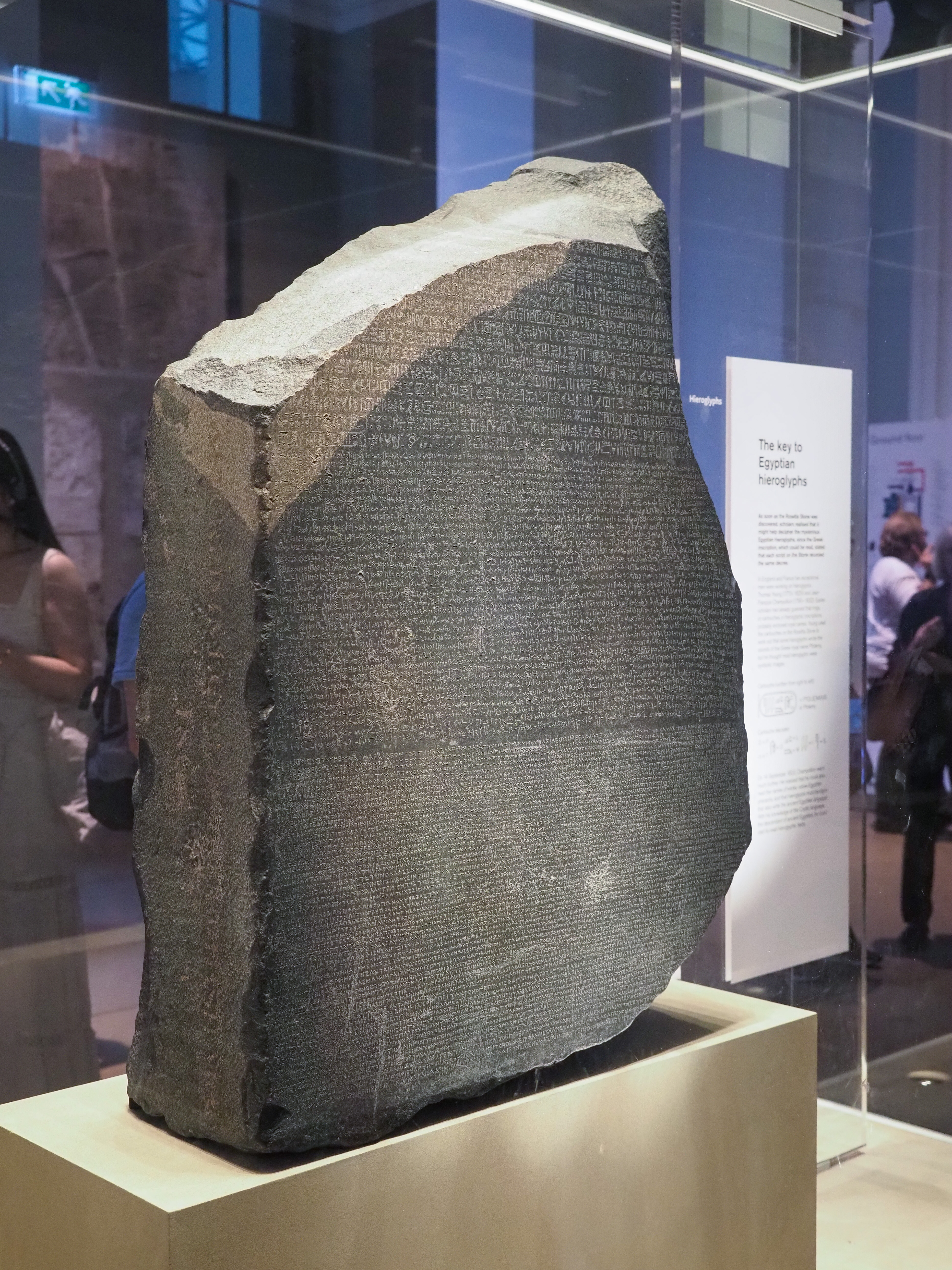

Rosetta << roh ZEHT uh >> stone gave the world the key to the long-forgotten language of ancient Egypt. A French officer of Napoleon’s engineering corps discovered it in 1799. He found the stone half buried in the mud near Rosetta, a city near Alexandria, Egypt. The Rosetta stone was later taken to England, where it is still preserved in the British Museum.

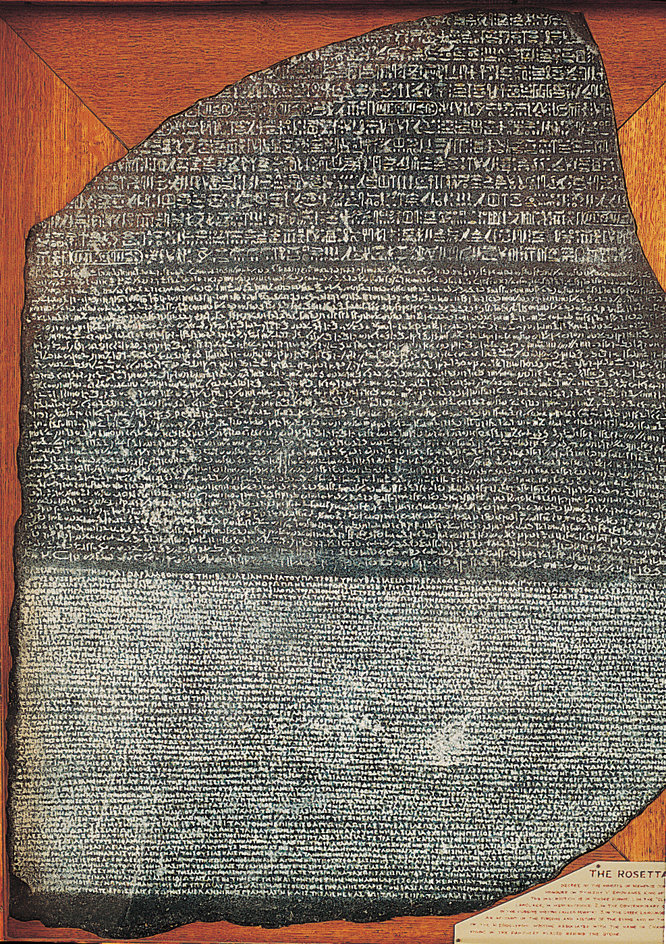

On the stone is carved a decree by Egyptian priests to commemorate the crowning of Ptolemy V Epiphanes, king of Egypt from 205 to 180 B.C. The first inscription is in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. The second is in demotic, the popular language of Egypt at that time. At the bottom of the stone the same message is written again in Greek. See Hieroglyphics.

The stone is made of a dark gray granitelike rock with a pinkish tone and a pink streak at the top. It is about 11 inches (28 centimeters) thick, 3 feet 9 inches (114 centimeters) high, and 2 feet 41/2 inches (72 centimeters) across. Part of the top and a section of the right side are missing.

The language of ancient Egypt had been a riddle to scholars for hundreds of years. A French scholar named Jean Francois Champollion used the Rosetta stone to solve the riddle. Using the Greek text as a guide, he studied the position and repetition of proper names in the Greek text and was able to pick out the same names in the Egyptian text. This enabled him to learn the sounds of many of the Egyptian hieroglyphic characters.

Champollion had a thorough knowledge of Coptic, the last stage of the Egyptian language that was written mainly with Greek letters. This knowledge enabled him to recognize the meanings of many Egyptian words in the upper part of the inscription. After much work, Champollion could read the entire text. In 1822, he published a pamphlet, Lettre a M. Dacier, containing the results of his work. This pamphlet enabled scholars to read the literature of ancient Egypt.