Sailing is a popular form of recreation and an exciting water sport. The thrill of sailing a boat in a fresh breeze attracts thousands of sailors to seashores, lakes, and rivers all over the world. They take to the water in sailboats that range in size from tiny dinghies to large yachts that can cross an ocean.

Many people enjoy racing their boats against other craft. For some, sailing brings the pleasure of leisurely hours on the water. Many people also love the challenge that competitive sailing and coastal cruises offer to their skill as sailors.

For hundreds of years, all great navies and merchant fleets of the world consisted of sailing vessels. Tall-masted ships with huge, billowing canvas sails traveled to all parts of the world. By the early 1900’s, however, steamships had almost completely replaced sailing vessels for military and commercial purposes (see Ship [Sailing ships in the 1900’s]). The development of sailing as a sport began when sailing ships declined in commercial importance.

Professional boatbuilders make most sailboats. Most of these boatbuilders work in European countries. Until the mid-1900’s, most boats had hulls made of wooden planking fastened over frames. Today, the great majority are built of fiberglass, though some are made of aluminum or steel. Carbon fiber composites are used in many racing boats and in some cruising yachts. Some amateurs build small wooden sailboats at home. The parts are sometimes supplied in a kit, and the builder simply fits them together. This is an especially popular way of building small boats called prams. Most prams are about 8 feet (2.4 meters) long and have blunt ends similar to the baby carriages known as prams. They are the smallest practical sailboats and are good for new sailors learning sailing fundamentals. There are also many other types of small boats suitable for both learners and experienced sailors.

The parts of a sailboat

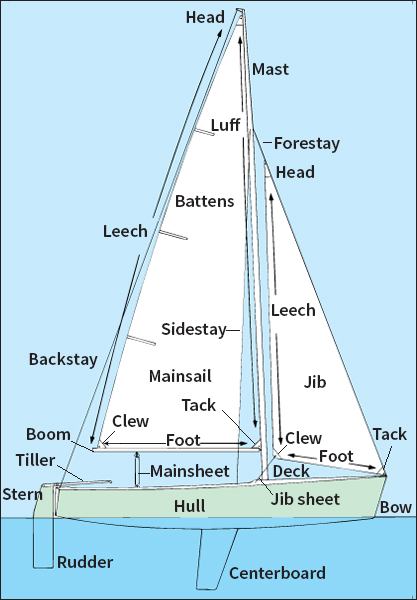

Each part of a sailboat has a special name. Sailors take great pride in using the proper terms. The main parts of a sailboat include (1) the hull, (2) the spars, (3) the sails, and (4) the rigging.

Hull

is the body of a sailboat. The front of the hull is called the bow, and the rear is called the stern. Forward, or fore, means front, and aft means rear. Almost all sailboats have either a keel or a centerboard. These flat pieces of metal or wood extend into the water from the bottom of the hull to limit movement to either side. A keel is fixed in place. But a centerboard can be raised or lowered through a slot in the bottom of a hull. Some boats, such as inland scows, may have two centerboards known as bilge boards. Other craft, such as sailing canoes, have leeboards, one on each side of the hull. Bilge boards and leeboards serve the same purpose as keels and centerboards. They prevent the boat from making leeway (sliding sideways in the water). The boat is steered with the rudder, a fin that extends vertically into the water near the stern. On small sailboats, the rudder is turned with a long handle called a tiller, and on larger boats, with a wheel.

Spars

are the poles that support the sails. They include masts, booms, and, depending on the type of boat, gaffs. Masts are the upright poles that hold the sails. The mainmast holds the largest sail. Some large sailboats also have a shorter mast, called a mizzenmast, toward the stern, or a shorter foremast toward the bow.

Booms and gaffs are the poles that extend at right angles to the masts and hold the sails straight out. Booms are fastened to the bottom of the sail, and gaffs are sometimes fastened to the top. However, gaff-rigged boats are rare.

Sails.

The mainsail (largest sail on a sailboat) is fastened to the back of the mainmast. A smaller, triangular sail in front of the mainmast is called a jib. A large jib that overlaps the mast and stretches far back next to the mainsail is called a Genoa jib, after the Italian port where it was first used. The spinnaker is a large, balloon-shaped sail used for added speed when a boat sails with the wind. Spinnakers are often made in red, blue, and other bright colors. Most sails are made from Dacron, a strong and tightly woven material that holds its shape well no matter how strong the wind blows. Spinnakers are usually made of nylon, which is strong, light, and elastic. Sails for racing boats are made from a laminate, in which load-bearing fibers are sandwiched between two layers of a clear synthetic material called Mylar. These laminated sails are light and hold their shape better than Dacron.

Rigging

includes the lines (ropes) used on a sailboat. Standing rigging is permanent and supports the masts. It includes shrouds that run from the sides of the boat to the mast, and stays that run from the bow and stern to the mast. Running rigging consists of the lines used to adjust the sails and booms. The lines that raise and lower the sails are called halyards. Those used to trim (adjust) the sails are called sheets.

Kinds of sailboats

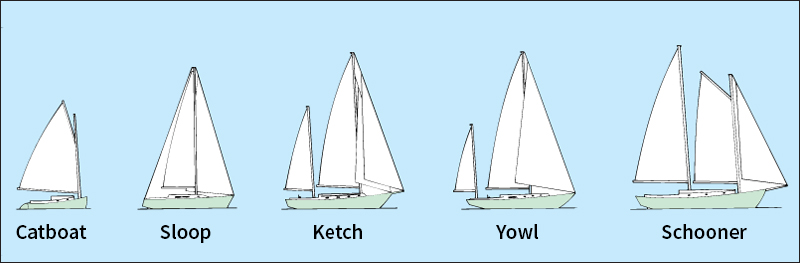

Sailboats are classified according to their size and the way their sails and masts are rigged (arranged). There are many combinations of sails and masts. The most common rigs include catboats, sloops, yawls, ketches, and schooners. Most small sailboats are catboats and sloops. Larger sailboats, especially those capable of ocean trips, are sometimes yawl-rigged, ketch-rigged, or (rarely) schooner-rigged in order to break the total sail area into smaller, more easily managed parts.

Catboats and sloops,

the most popular sailboats, are easy to sail and comparatively cheap. A catboat has one mast far forward in the bow, and only one sail. A sloop has one mast toward the middle of the boat, and two sails, a mainsail and jib. A large sloop with two jibs is sometimes called a cutter. Many sailors start out by learning to sail in dinghies as children. Some dinghies are rigged as catboats. Other dinghies have a conventional sloop rig. Inland scows are popular on lakes. These light, fast boats are usually sloop-rigged. They have a rounded bow and a square stern, and are flat-bottomed. Scows usually have two bilge boards and two rudders.

There are several hundred classes of catboats and sloops. Each class is built slightly differently as to the design and size of its hull, sails, and rigging. These classes are known as one-design classes—that is, all the boats in a particular class are built to exactly the same measurements. Each class has its own name, such as Snipe, J/70, Etchells, and Star. The Sunfish and Laser are among the world’s most popular classes.

Yawls, ketches, and schooners

are usually larger and more expensive boats, and few are built today. All have two masts. A yawl has at least three sails—a jib, a mainsail, and a mizzensail. The mizzenmast is stepped (positioned) in the stern behind the rudder post. A ketch also carries three or more sails, but the mizzenmast is in front of the rudder post. A schooner has a mainmast in about the middle of the boat and a foremast. It has the most sails, with one or more jibs, a foresail, and a mainsail. These larger boats usually have comfortable living quarters that make them popular for long trips. Multihull sailboats became popular in the 2000’s, largely because of the adoption of catamarans by Caribbean charter fleets. With their two hulls, cruising catamarans have a great deal of interior space and vast deck areas. They are usually sloop-rigged. Smaller daysailing and racing catamarans such as Hobies are also popular. Some can rise above the water on curved foils for exciting bursts of speed. Three-hull trimarans are increasing in popularity. Some have collapsible or folding amas (outriggers or floats), allowing them to be transported by trailer on public roads.

Sailing a boat

Even a log raft with a goatskin tied to a pole will sail before the wind. Such a craft was probably the first sailing vessel. To sail in other directions, a boat must be designed and rigged so that the force of the wind moves it across the wind or into the wind, as well as moving it with the wind.

Controlling direction.

A boat with no means of control will travel straight downwind (in the direction toward which the wind is blowing). It will do this no matter which direction its bow or stern is pointing. It may even go sideways. Using a rudder is the first step in controlling a boat. With a rudder, the bow of the boat can be pointed in the desired direction.

But a rudder is not enough to control a boat. A boat must also have something to keep it from sliding sideways when moving across the wind. This is done with a keel, centerboard, daggerboard, bilge boards, or leeboards. Boats with keels can sail only in water deeper than the keel. Boats with movable keels—such as centerboards, daggerboards, and bilge boards—can sail in shallower water, because such keels can be raised or lowered through the bottom of the boat as needed. Leeboards are a simple way of changing a canoe or rowboat into a sailboat. They can be swung out of the water when not needed.

With a rudder for steering and a keel or centerboard to prevent sideward movement, a sailboat can travel in many directions. The bow of a sailboat is usually sharply pointed, so it can cut through the water easily.

Why a boat sails.

A sail is not a flat piece of cloth. A sail has curved panels sewn into it so it will be shaped like the wing of an airplane when the wind fills it out. The side of the sail to leeward (away from the wind) corresponds to the top of an airplane wing. The action of the wind blowing across this curved surface creates a lift similar to the force that enables an airplane to stay in the air. See Aerodynamics. In a sailboat, this lifting force becomes a pull away from the sail and toward the bow of the boat. At the same time, the wind also exerts a push against the other side of the sail. In this way, the action of the wind on the sail combines in two ways to force the boat forward. These forces make it possible to sail a boat in almost any direction, except directly into the wind and up to 45 degrees on each side of the wind direction.

Basic sailing maneuvers.

There are three basic sailing maneuvers: (1) sailing into the wind, (2) sailing across the wind, and (3) sailing with the wind.

Sailing into the wind

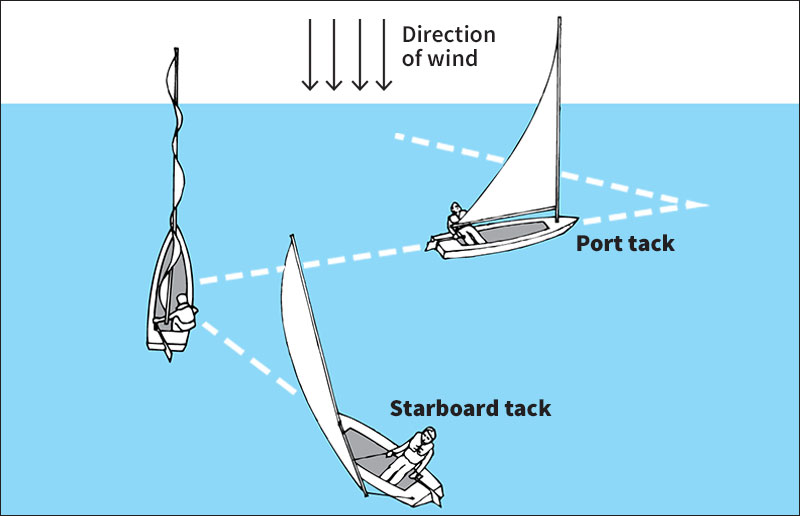

is called sailing close-hauled, sailing on the wind, or beating to windward. No boat can sail directly into the wind. If it does so, the sail flaps like a flag and becomes useless. But a boat can sail upwind by tacking, or following a zig-zag course. In general, a sailboat can head to within 45 degrees of the direction from which the wind is blowing before its sail starts to luff (flap) and lose its driving force.

Sailing to windward requires great skill. The wind almost never blows constantly with the same force from the same direction. The speed with which a sailor’s tacks bring a boat to a certain point upwind depends on the sailor’s ability to feel the little shifts and changes in the wind, and to adjust the sails and the boat’s direction, or course, accordingly.

Sailing across the wind,

with the wind abeam, is called reaching. Sailboats can usually move faster when sailing across the wind than in any other direction. Some light sailboats with flat bottoms can move fast enough in a good breeze to lift out of the water and plane on the surface like a motorboat. This gives a great sensation of speed in smaller boats.

Sailing with the wind

is called sailing before the wind or running. Contrary to what might be expected, running is not so fast as reaching. In running, the sail is simply pushed along by the wind and makes its own resistance. Many racing boats use spinnakers for added speed when running. These sails lift the boat along.

Trimming and tacking

are two basic skills all sailors must learn in order to handle their boats effectively.

Trimming means adjusting the sails to obtain the full advantage of the available wind. A sailor must always know the wind direction in order to trim the sails correctly. When the boat is running before the wind, the mainsail is at right angles to the boat’s direction. When the boat is reaching (sailing across the wind), the mainsail extends about halfway out from the boat, or at about a 45-degree angle to its direction of travel. When the boat is sailing into the wind, the sails should be trimmed nearly parallel to the boat’s direction.

Small sailboats can easily capsize (overturn) if mishandled. Experienced sailors know where to place their weight and how to relieve dangerous pressure on the sails if a boat tips too far. This is done by slacking off—that is, letting the sails out so some of the wind spills from them. If a boat does capsize, the crew should hang on to it until rescued, unless it is of a type that can be righted and sailed. All sailors, especially those who are weak swimmers, should always wear life jackets. See Swimming (Water safety).

Tacking involves turning the boat so that the wind comes at it from the opposite side. When sailing into the wind, this is called coming about. In coming about, the bow is turned so that the wind crosses it. This is a comparatively safe maneuver. When the stern is to the wind, a turn that brings the wind to the other side of the boat is called jibing. Then, the wind crosses the stern quickly, and the boom slams across the boat. This quick shift of forces can capsize a boat if the maneuver is not handled carefully and with skill.

Sailboat racing

One-design races.

The largest number of races are held for the smaller craft that make up the many one-design classes of boats. The boats usually sail over triangular courses in protected waters near a local yacht or boating club. These are evenly matched races, because all the boats in a particular class are designed and built alike. This makes the skill of the skipper and crew the most important factor in winning a sailboat race.

But the care with which a crew maintains its boat and prepares it for a race is also important. The way the crew members adjust the rigging and sails has much to do with a boat’s speed. A bad paint job on a sailboat’s bottom will slow it down, because the boat will not slip through the water easily.

Handicap races

involve boats of different sizes and designs. All the boats cross the starting line together, but the smaller boats have a handicap (time allowance). A smaller boat can win even though it finishes far behind a larger boat. Most long ocean races for larger sailboats are handicap races. Some of the best-known races are from Annapolis, Maryland, to Bermuda; from Los Angeles to Honolulu, Hawaii; from Newport, Rhode Island, to Bermuda; and the Mackinac Races from Chicago and from Port Huron, Michigan, to Mackinac Island in the Straits of Mackinac. Other important races are the Sydney-Hobart race in Australia and the Fastnet Race between the southern coasts of England and Ireland.

America’s Cup

is the world’s most famous sailing competition. A yacht representing a yacht club from one nation challenges the defending champion for a cup first won in 1851 by the schooner America. Elimination races determine the yachts that will represent the defending champion and the challenger. The first yacht to win a set number of races wins the cup. For more information, see America’s Cup.