Salem witchcraft trials were the largest set of witchcraft trials in American history. The trials, which took place in 1692, centered around Salem Town (present-day Salem, Massachusetts) and Salem Village (present-day Danvers) in Essex County in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The trials resulted in the arrest and imprisonment of between 150 and 200 people, about 50 confessions, the execution of 14 women and 5 men, and the death by torture of 1 man. Four adults and at least one infant died in jail. Only two colonial American witchcraft trials would follow the Salem trials, and both of those ended in acquittal.

Background.

Witchcraft belief was nearly universal in England and its North American colonies in the 1600’s. Belief in witchcraft was considered part of orthodox Christianity, and doubts about the reality of witchcraft were generally equated with atheism. Although witchcraft belief was commonplace, the scale of the trials at Salem was unprecedented in the colonies. Indeed, the Salem trials account for more than half of the 35 known executions for witchcraft in colonial New England.

The witchcraft panic

at Salem began in January 1692 in the house of the Salem Village minister Samuel Parris. Parris’s young daughter and her cousin started to have strange fits. A doctor determined that their illness was not natural. A neighbor encouraged the minister’s slaves, John and Tituba, to perform a ritual intended to reveal the identity of any witches harming the children. The ritual supposedly revealed that Tituba was the guilty party.

Over the next several months, a group of young people claimed to have spectral sight—that is, the ability to see phantoms. The group claimed to see scores of witches. Other Massachusetts Bay residents alerted authorities to neighbors they suspected of witchcraft. In April, Abigail Hobbs claimed to have met the devil in Maine. Ann Putnam, Jr., claimed that George Burroughs, a former minister in Salem Village and then-minister in Maine, appeared to her and tried to force her to sign the devil’s book. Putnam said that Burroughs had confessed to several murders, including the murders of a number of soldiers fighting a French and native alliance in King William’s War (1689-1697) on the Maine frontier. The respected minister Cotton Mather called Burroughs the witches’ leader, who sought to bring about the downfall of the church in New England. After Hobbs and Putnam connected the Salem witchcraft panic with the war in Maine, accusations of witchcraft increased dramatically.

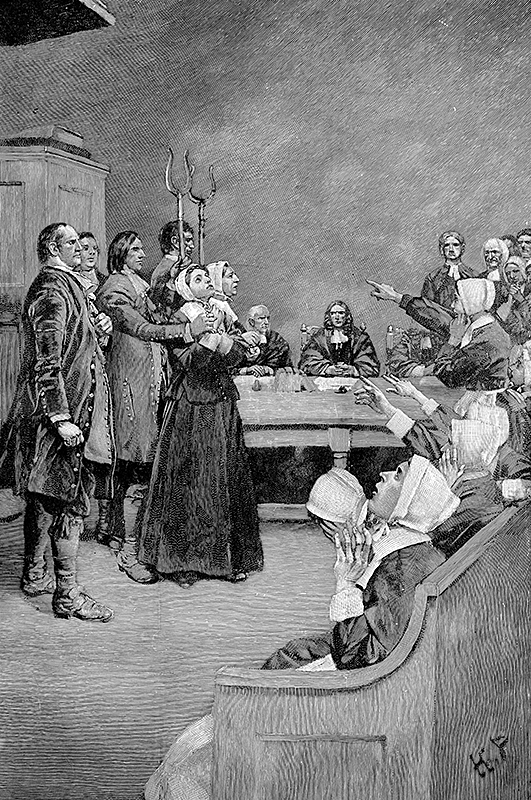

The witchcraft trials

themselves began nearly six months after the girls in Parris’s household fell ill. Massachusetts Bay’s government was of questionable legality in the period between 1689 and the arrival of a royal charter in June 1692. This government was reluctant to embark on difficult, capital trials while it was unsure of its own authority. As a result, the delay between the first witchcraft accusations and the first trials filled the jails with suspects. When the royal Governor William Phips set up a temporary court to try the witchcraft suspects, the court convicted every suspect it tried and sentenced each to hang. In October, Phips—sensing that public opinion was turning against the trials—disbanded the court and ended the executions.

The witchcraft scare lasted about a year. The colony’s leading ministers helped stop it. In 1693, the people still in jail on witchcraft charges were freed. In 1711, the colony’s legislature made payments to the families of the witch-hunt victims.