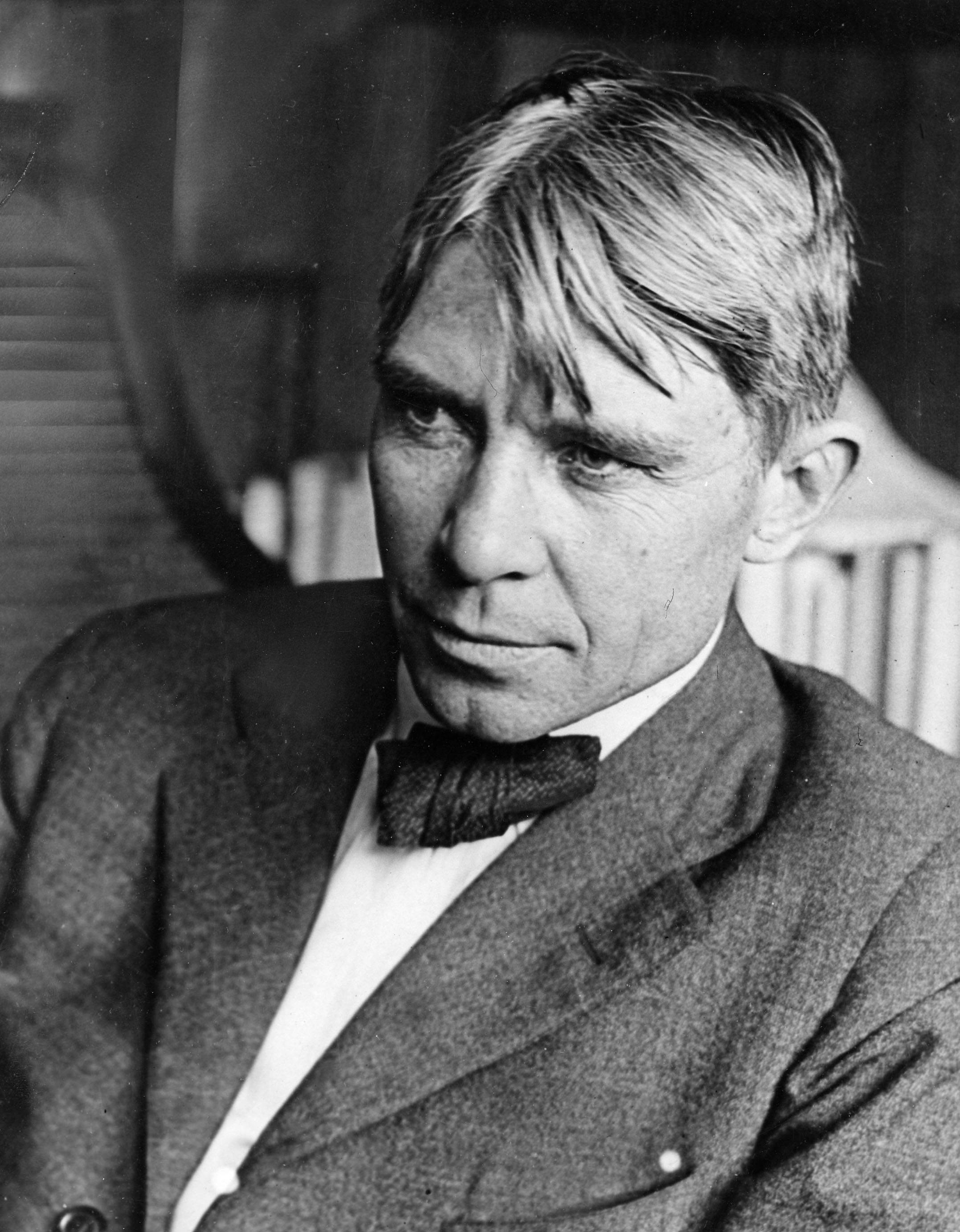

Sandburg, Carl (1878-1967), was an American poet, biographer, and historian. Two major themes dominate his works. One is a search for the meaning of American history. The other involves his enthusiasm for the common people of the United States. Quoting the English writer Rudyard Kipling, Sandburg said of himself: “I will be the word of the people. Mine will be the bleeding mouth from which the gag is snatched. I will say everything.”

Sandburg was born on Jan. 6, 1878, in Galesburg, Illinois. He left school at the age of 13 and did odd jobs around Galesburg for several years. Sandburg described his boyhood in the small Midwestern town in his highly praised autobiography, Always the Young Strangers (1953). Its sequel, Ever the Winds of Chance (1983), was published after his death. It describes the years from 1898 to 1907.

When he was about 18, Sandburg traveled throughout the Midwest as a hobo. After the Spanish-American War began in 1898, he served briefly in the U.S. Army in Puerto Rico. That same year, he returned to Galesburg, where he attended Lombard College. He left college in 1902 without graduating. For about 10 years, he was active in Socialist Party politics in Wisconsin.

Sandburg worked as a newspaper writer, primarily in Chicago, from 1912 to the late 1920’s. He first won fame—for his poetry—during that period. Then the success of the first part of his great biography, Abraham Lincoln, enabled him to leave journalism and concentrate on a literary career. Sandburg was one of several important American writers who lived in Chicago from about 1912 to the mid-1920’s. These writers included Sherwood Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Ben Hecht, and Edgar Lee Masters. They are frequently called the Chicago School.

His poetry.

One of Sandburg’s best-known early poems, “Chicago” (1914), portrays the brutality and ugliness he saw in American cities. The poem also pays tribute to the energy and power of modern industry. In making the city his subject, Sandburg followed a tradition in American poetry. That tradition began with Walt Whitman during the mid-1800’s. In form, style, and theme, many of Sandburg’s works resemble the poems in Whitman’s collection, Leaves of Grass.

After 1920, Sandburg began to collect American ballads, folk tales, and legends. He presented many ballads and folk songs in The American Songbag (1927).

Sandburg introduced much American folklore into his poetry. In his long free-verse poem The People, Yes (1936), he included tall tales about fictional and real characters. They included Paul Bunyan and Christopher Columbus. Sandburg ended the poem with the American people vigorously on the march. The people were seeking new forms of self-expression, and asking the questions, “Where to? What next?”

Sandburg believed deeply in the value of life, and he strongly opposed war. In his dramatic short poems “Grass” (1918) and “A.E.F.” (1920), Sandburg protested against the folly and waste of war.

Some critics consider Sandburg’s poetry crude and sentimental. But most critics agree that he accomplished his goal of being the voice of the American people and a spokesman for American democracy. Sandburg’s Complete Poems (1950) won the 1951 Pulitzer Prize for poetry.

His prose.

To Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln represented all that was best in the American character. Sandburg also regarded the American Civil War as the most important event in the country’s history. From 1920 to 1939, he wrote six volumes of history about Lincoln and the Civil War. In Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (two volumes, 1926), Sandburg dealt with Lincoln’s career up to his election as President. Then, in Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (four volumes, 1939), Sandburg provided one of the fullest accounts of Lincoln’s presidency ever written. For this work, Sandburg received the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for history. Many people rank this work as the finest historical biography of the 1900’s.

Sandburg wrote three volumes of humorous stories for children. They are Rootabaga Stories (1922), Rootabaga Pigeons (1923), and Potato Face (1930). He also wrote a historical novel, Remembrance Rock (1948). He died on July 22, 1967.