Ship is a large, seagoing vessel. Ships are among the oldest and most important means of transportation. Every day, thousands of ships cross the oceans, sail along seacoasts, and travel on inland waterways. Some ships are simple wooden vessels. Other ships rank among the largest moving structures ever built. These huge cargo ships crisscross the oceans, forming a vital network of trade among countries. Military forces rely on ships for transporting troops and equipment. The largest military ships, called aircraft carriers, are floating military bases that launch warplanes.

All ships have a watertight shell called a hull. The hull is shaped to cut through water. Other structures on a ship help the vessel steer and remain stable. Human muscle powered the earliest ships, by paddling or rowing. Wind supplies the power to move sailing ships. Most modern ships burn fuel for power. Nuclear energy propels a small number of large ships, almost all of them military vessels.

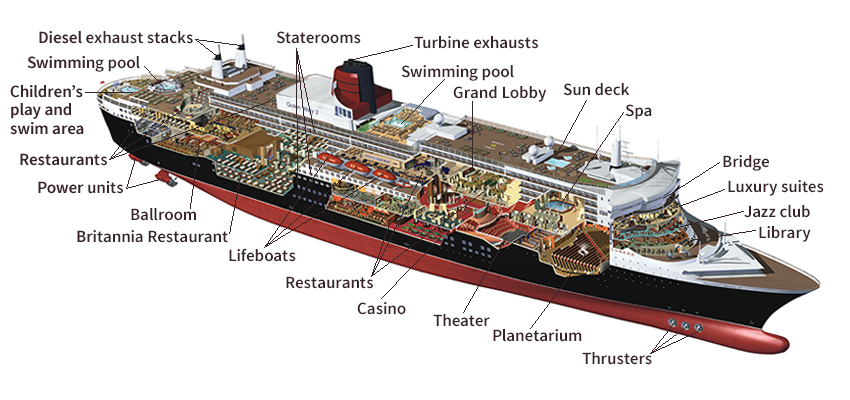

Ships can be classified based on their purpose. Most ships today are cargo ships. They carry raw materials or manufactured products. Container ships are designed to transport giant boxes filled with many kinds of cargo. Tankers carry liquid cargo, usually oil. Dry bulk carriers transport such raw materials as grain or metal ore. Other ships are designed for such specialized tasks as breaking through ice-covered waterways or towing other ships. Passenger ships are designed to carry people—often in luxurious fashion.

Ships are designed by experts called naval architects. A ship is almost always built near water, because it would be difficult or impossible to transport a ship overland.

Life on a ship can be quite different from life on land. At sea, a ship must be self-sufficient, carrying everything needed by the vessel, its passengers, and its crew. Many modern ships have automated equipment. But even the most high-tech ship requires a team of officers and crew. Maritime law and other rules govern how ships can be operated and built. Each ship must fly the flag of a certain country. A country’s merchant marine includes all of the commercial ships that fly its flag.

Ships offer many comforts and economic advantages. But ships can also cause pollution and other forms of environmental damage. Oil spills from tankers rank among the most disastrous environmental accidents.

For thousands of years, people have been drawn by the mysteries of the sea and by its promise of adventure. Among the earliest sailors were people who crossed the Mediterranean Sea to settle on the island of Crete almost 130,000 years ago. Many of the world’s great civilizations relied on ships for trade, exploration, settlement, and conquest. Ship technology improved over time, enabling seafaring people to sail farther and farther from shore. Beginning in the 1400’s, European sailors crossed the Atlantic Ocean into the “New World” of North and South America, forever changing ways of life in both places. During the mid-1800’s, steam-powered ships began to replace sailing vessels. Distant places drew closer as steamships crossed the seas in a fraction of the time that sailing ships needed. Throughout history, ships have brought countries and peoples closer together and increased their economic dependence on one another.

The difference between a ship and a boat is chiefly a matter of size. Large seagoing vessels that carry everything they need to cross oceans are called ships. Boats are smaller craft dependent on shore-based activity. This article deals mainly with commercial ships. It also covers the history and development of ships. For more information on military ships, see Navy. For more information on the operation of fishing ships, see Fishing industry.

How ships work

Buoyancy is the ability of an object to float in water. Ships float because they weigh less than the volume of water they displace. If a ship becomes heavier than an equal volume of water, the ship will sink.

Ships move from one spot to another by means of a propulsion system. Wind-powered sails were once the most common form of propulsion. Modern ships mostly use propellers driven by engines. A structure at the back of the vessel called the rudder enables people to steer ships.

A modern ship is one of the most complicated objects ever made. Ships are much like floating cities. They must generate their own power, heat, and electricity. A ship carries its own fuel and provisions and must dispose of its own garbage. Some ships can make their own fresh water from the sea.

Basic structure.

Sailors and other nautical experts use specialized terms to describe the parts of ships. A ship’s front is called the bow (pronounced to rhyme with cow). The back of a ship is the stern. The right side of a ship is starboard, and the left side is port.

The hull is the watertight shell of a ship. A hull may be as simple as a bottom “skin” of animal hide, metal, or another material. More complex hulls are divided into a number of horizontal surfaces called decks, which are much like the floors of a house. Bulkheads are vertical walls built between the decks, forming compartments. Each compartment has special doors that, when closed, can make it watertight. If water floods a compartment, closing the doors will trap the water there, preventing the flooding of other compartments. Watertight compartments enable a ship to float even with a hole in its hull.

The deck at the top of the hull is called the main deck. More decks may lie above it at the bow and stern. All the structures above the main deck make up a ship’s superstructure. The bridge is the area from which a ship is navigated and commanded.

Hulls generally have pointed bows so they can cut easily through the water. Most hulls also have rounded sterns, which helps the water close smoothly behind the ship. The overall shape of a hull is designed to make the ship as stable as possible. A ship must not roll (rock from side to side) or pitch (rock from front to back) too much. When a ship rolls over on its side, it is said to capsize.

Most modern ships use stabilizing systems to reduce rolling. One such system has a horizontal underwater fin on each side of the hull. The fin moves upward on the descending side of the ship and downward on the ascending side and so reduces the roll.

The keel is often called a ship’s backbone. It is a long fin or blade that runs down the center of a hull’s bottom. The keel helps to keep a ship stable and to ensure that it moves forward, rather than side to side.

To further increase stability, ships carry extra weight called ballast. Without ballast, an empty cargo ship would bobble about in the ocean like a cork. Many large vessels use seawater as ballast. As a ship takes on heavy cargo, the ballast water is pumped out.

Modern ships usually have an anchor on the port and starboard sides of the bow. Power-driven winches raise or lower the anchors. Winches also bring in or let out the mooring lines used to tie the vessel to a pier or wharf.

Shipboard pumps can quickly pump out ballast water or pump up seawater in case of fire. In addition, a ship typically carries enough lifeboats to hold all persons on board. Radio-telegraph equipment and satellite phones keep ships in constant touch with the rest of the world.

Propulsion and steering.

Wind was once the main power source for ships. Over centuries, shipbuilders learned to make ships with greater numbers of sails for collecting the wind. Sails remained a central part of ship design until the 1800’s. At first, even engine-powered ships had sails.

Sailing ships relied on favorable winds, currents, and weather. Ships with engines could depart and arrive when they wished, in all but the most extreme weather conditions. By the 1880’s, engines were considered reliable enough to function on their own, without sails. Today, virtually all sailing ships are used for recreation, racing, or education, rather than commercial purposes.

Almost all ships, regardless of their propulsion type, are steered with a rudder. The rudder is a large, flat, vertical piece of metal that is hinged to the stern. It can be swung left or right like a door. The rudder’s movement causes the ship to turn. The rudder is connected to the helm on the ship’s bridge. Traditionally, the helm was a wheel that, when spun by a sailor, caused the rudder to move. Modern ships are more commonly steered with electronic joysticks.

A ship’s speed is measured in units called knots. A knot is equal to one nautical mile per hour. A nautical mile equals 1.852 kilometers, or 1.151 land miles.

Sailing ships

have a number of specialized parts that support and work with the sails. Masts are large vertical posts that hold up the sails. The simplest sailing ships have only one mast. The huge American cargo ship Thomas W. Lawson (1907), on the other hand, had seven masts, each named for a different day of the week. A ship’s rigging includes all the masts, ropes, and other structures that hold up and control the sails.

The keel plays an especially important role in sailing. It prevents a sailing ship from simply being blown in the direction of the wind. The keel essentially blocks the wind from pushing a ship sideways, transforming the wind’s push into the ship’s forward motion. Ships with keels can thus harness the wind to sail in almost any direction. Sailing directly into the wind is impossible. But a ship can still zigzag at angles to the wind. This method, called tacking, enables a ship to slowly move in the wind’s direction. For more details on how sailing works, see the article Sailing.

Engine-driven ships

are pushed through water by rotating propellers, also called screws. Most propellers have four blades. As a propeller turns, it screws itself through the water, pushing the ship forward. Most small ships have one propeller. Many larger vessels have two propellers, and extremely big ships have four. Additional propellers increase a ship’s power and make the vessel easier to maneuver. For example, a twin-screw ship can be swung around quickly by going forward on one propeller and backward on the other. Some ships have extra propellers called bow thrusters. These propellers, located in the bow, help turn the ship more rapidly than do stern propellers alone.

Modern ships use a variety of engine designs to spin their propellers. The largest and fastest ships use steam turbines. These ships boil water to produce steam. The steam pushes the bladed wheels of a fanlike turbine, causing it to spin. The turbine, in turn, connects to and spins the propeller through a series of gears. Most ships burn petroleum to boil the water and produce steam. Nuclear-powered ships use a nuclear reactor to generate the heat that boils the water. Some ship turbines are spun by hot gases other than steam.

Vessels propelled by diesel engines are called motorships. They have either geared-drive or diesel-electric machinery. On a geared-drive ship, the engine works through gears to turn the propeller. On a diesel-electric ship, the engine turns a generator that supplies current to an electric motor, which drives the propeller shaft.

Kinds of ships

Most oceangoing ships today are cargo ships, loaded with goods and raw materials for trade. These ships are designed for efficiency and economy. Over time, cargo vessels have become bigger and bigger, chiefly for economic reasons. For example, shippers have found it far cheaper to transport a large amount of oil in one huge tanker rather than in several smaller ones. Also for economic reasons, shipbuilders have designed vessels that can be loaded and unloaded in minimum time with minimum labor. In addition, cargo ships are usually highly automated so they can be run by small crews.

Large cargo ships need special port facilities. The ships may require deep channels to get into port. Giant cranes and other lifting equipment must be used to move cargo containers off the ships and to stack them on land. The most advanced ports use computers and bar coding to ensure that containers reach proper loading and pickup areas.

Traditional general cargo ships.

During World War II (1939-1945), shipyards in the United States built more than 3,000 standardized ships. These ships were known as Liberty and Victory ships. Both types of ship were about the same size. But Victory ships, powered by steam turbines, were faster than Liberty ships, which used less advanced steam engines. Both ships were built according to standard plans. This standardization enabled them to be mass produced. They carried millions of troops and millions of tons of supplies to battlefields in many parts of the world.

Since World War II, the general cargo ship has steadily advanced. Such ships use automatic engine room controls and navigation equipment. Yet traditional cargo ships have been declining steadily in use, chiefly because of high operating costs. A typical smaller cargo ship may carry automobiles, sacks of flour, airplane engines, crates of chinaware, and a variety of other items. Loading and unloading such a mixture of items of varying shapes and sizes requires much time and labor. It is therefore expensive. As a result, there has been an increase in the number of ships designed to carry only a single type of cargo. Such ships include tankers and dry bulk carriers.

Container ships

eliminate many of the expenses associated with the traditional general cargo vessel. Like traditional cargo ships, container ships are said to be general cargo ships because they can carry a mixture of items. The hull of a container ship is simply an enormous floating warehouse. It is divided into cells by vertical guide rails. The cells are designed to hold cargo in prepackaged units called containers. Most containers consist of a metal box of standard size. Some containers measure 20 feet by 8 feet by 8 feet (6.1 meters by 2.4 meters by 2.4 meters). Other containers are twice as long, about the size of a railroad car.

Manufacturers load finished goods—anything from perfume to electronic products—into the containers, which are provided by the shipping company. The containers are then delivered to the dock for loading onto the container ship. Giant cranes pick up the containers, swing them over the ship, and then stack them in the cells. After the hold has been loaded, additional containers are stacked on the deck.

Container freight saves shippers much money. A container ship can be loaded and unloaded in a small fraction of the time it takes for a traditional cargo vessel. Thus, labor costs are cut sharply. There is also less breakage and less danger of cargo shifting during a voyage. In addition, far less is lost to theft because the containers are sealed.

The largest container ships measure about 1,300 feet (400 meters) long. They can carry thousands of 20-foot (6.1-meter) long containers, holding a total of about 170,000 tons (150,000 metric tons) of cargo. These ships can make a round trip between Europe and the United States in 21 days. Because of this quick turnaround, each of these ships equals the cargo-carrying capacity of 17 standard World War II freighters.

Many shipping companies believe that containerization is the greatest advancement in shipping since the invention of the steamship. Containerization of cargo began about the mid-1950’s. Today, major shipping companies throughout the world operate or are building fleets of container ships.

Roll-on/roll-off ships,

also known as ro-ro ships, carry containers mounted on a framework of wheels like a truck trailer. These ships have an opening in the stern and side openings. Dockworkers drive the containers up ramps onto the ships. They take the containers to their assigned places by way of inboard ramps or elevators. Ro-ro ships also haul cars, buses, house trailers, trucks, and any other cargo that can be rolled aboard.

Tankers

were among the first ships designed to carry only one kind of cargo—petroleum. Earlier ships carried oil in barrels and then in large tanks. In 1878, Ludwig Nobel of Sweden launched a ship that was simply one great tank itself. Nobel was the brother of Alfred Nobel, founder of the famous Nobel Prizes. Ludwig’s tanker hauled oil from the Baku fields in southeastern Russia (now part of Azerbaijan) across the Caspian Sea.

In 1885, the first oceangoing tanker, the Glückauf, was launched. This ship was built in the United Kingdom for a German oil company. It carried petroleum from the United States to Europe. The Glückauf became the model for all later tankers. Its hold space had eight big tanks, and its engine room was set in the stern to reduce the danger of fire. The vessel was 300 feet (90 meters) long and 37 feet (11 meters) wide. It carried 2,300 tons (2,100 metric tons) of oil and could travel at 9 knots.

Today, large tankers, often called supertankers, can measure up to 1,500 feet (460 meters) long and around 220 feet (67 meters) wide. An average supertanker can carry around 3.1 million barrels of oil. It can travel at about 16.5 knots. Most supertankers are used to transport oil from the Middle East to Europe and Japan. They have double hulls for safety.

Supertankers have various economic advantages over smaller tankers. For example, it costs much less to transport a large amount of oil in one supertanker than in many small tankers. But supertankers also have major disadvantages. Their huge size makes them difficult to steer and increases the risk of accidents. Because of their size, the largest supertankers require ports more than 100 feet (30 meters) deep in order to unload. If a supertanker suffers an oil spill, the pollution that results can be disastrous.

Most tankers carry petroleum. But some tankers are designed to haul other kinds of liquid cargo, such as liquid natural gas (see Tanker (Liquefied natural gas (LNG) carriers)). Ships called ore/bulk/oil carriers (OBO’s) can serve as either tankers or dry bulk carriers.

Dry bulk carriers

transport fertilizer, grain, ore, powdered detergents, salt, sugar, wood chips, or any other cargo that can be piled loose into a hold. The first modern bulk carriers included specially designed boats that began hauling iron ore on the Great Lakes during the late 1800’s. Like tankers, these vessels were designed to carry only one kind of cargo. But unlike tankers, the ore carriers hauled solid cargo. As a result, they required more complicated loading and unloading arrangements than tankers. Tankers needed little more than hose connections and pumps.

The Great Lakes ore carrier resembled a long steel box. Between the bow and stern, there was a long bin to hold iron ore. Modern Great Lakes freighters have the same basic design. But they are larger than the earlier carriers. The largest vessels today are more than 1,000 feet (300 meters) long.

Oceangoing bulk carriers have also grown larger and larger. The biggest ones can carry as much as 70,000 tons (63,500 metric tons) of cargo. A modern seagoing bulk carrier has the bridge and engine room near the stern. The rest of the ship is a level area of deck with a line of hatches.

Passenger ships.

Until the late 1940’s, the most famous ships were the great oceangoing passenger liners. France, Germany, and the United Kingdom built most of these magnificent floating hotels. The liners stressed speed, luxury, and service. In addition to the regular crew in the deck and engine room, the ships employed a large staff of cabin and dining room stewards, cooks and bakers, and other service workers.

In the 1950’s, more and more people began to travel across the sea by airplane, rather than by ship. Today, only a few cruise ships sail the oceans as passenger vessels. Although few in number, these ships provide all-inclusive vacations to millions of people each year. They often travel to exotic world destinations that would otherwise be unreachable.

Specialized vessels.

Many ships are designed to do particular jobs. Refrigerator ships, traveling 22 knots, speed fresh fruits, meats, and vegetables across the ocean. Tugboats tow barges along canals and rivers. They also guide huge passenger liners and freighters in and out of harbors. Oceangoing tugs take part in rescue and salvage work. Ferries transport automobiles and passengers. Train ferries carry railroad cars across small bodies of water.

Powerful icebreakers use their sturdy bows to ram through frozen waters, opening a passage for other ships and boats. Oceanographic ships carry instruments to study currents, tides, waves, and the living things of the sea. Some modern fishing vessels are used not only to catch fish, but also to process them. These factory trawlers have equipment to clean and refrigerate the fish.

A ship at sea

The experience of being at sea is quite different from being on land. Even on ships with stabilizers, the wind, waves, and currents can cause a ship to roll constantly. Some people are prone to long periods of motion sickness on ships. The British admiral Horatio Nelson, for example, was subject to seasickness throughout his long and famous naval career.

A ship must be self-contained. It carries with it all the things needed to keep its crew and cargo safe. Ships must hold enough food, water, medicine, fuel, spare parts, safety gear, navigation and communication equipment, and many other tools both for everyday and emergency use.

Officers and crew.

A highly organized team of officers commands a modern ship. The top officer, called the captain or master, has final authority over and final responsibility for the passengers, the crew, the cargo, and the ship itself. The captain has a number of deck officers, called mates, as assistants. All these officers must have a license, which they receive after passing a test given by a national government or some other authority. The U.S. Coast Guard issues licenses to officers on American merchant ships.

The deck crew consists of able-bodied seamen (A.B.’s) and ordinary seamen. On American ships, both groups of seamen must hold certificates issued by the Coast Guard. Able-bodied seamen have more experience than ordinary seamen. They have tasks requiring greater skill and responsibility, such as standing lookout, helping steer, and making difficult repairs. Ordinary seamen do maintenance work.

The engine room crew has a separate organization. It is headed by a chief engineer, who is aided by assistant engineers. Like the captain and deck officers, all the engineers must have a license. The crew members in the engine room of a ship driven by steam turbines include oilers and firemen. Oilers help tend the engines. Firemen fuel the boilers.

A ship also has a number of other crew members. They might include a radio operator; a chief steward, who is in charge of obtaining, preparing, and serving food; one or two cooks; and a mess staff, who serve the meals and assist the cooks.

Cargo and passenger ships carry the same basic groups of crew members. But large passenger liners and cruise ships have much larger crews, to make a voyage as pleasant as possible for the passengers. The extra crew members include bakers, barbers and beauticians, bartenders, butchers, doctors and nurses, entertainers, housekeepers, launderers, accountants, recreation directors, and a large staff of stewards and stewardesses. A big passenger or cruise ship may carry as many as one crew member for every two passengers.

Navigation.

The first part of any ship’s journey is leaving port. Some large ships use thrusters—that is, small propellers or jets—to move away from piers. Other ships employ tugboats. The tugboats pull the ship from the pier into the harbor. A docking pilot directs the tugs and the ship until the vessel clears the pier and is underway in the harbor.

Every merchant ship leaves port with a local harbor pilot aboard. The harbor pilot guides the ship from the harbor into open water. The harbor pilot must know every channel, turn, sand bar, and other obstacle that could endanger the vessel. After a ship reaches open water, a small boat comes out and carries the pilot back to port. The ship’s officers then navigate the vessel to its destination. Ships also employ harbor pilots to guide them into harbors from the open ocean.

Modern ships have highly accurate electronic navigation equipment for determining their position anywhere on the globe. Many ships use the Global Positioning System (GPS), which determines position using signals transmitted from orbiting satellites.

Modern ships also use radar. At night and in bad weather, a ship’s radar can spot icebergs, rocks, and other vessels in time to prevent a collision. Some modern ships also have an automatic pilot. The autopilot can hold a ship on a set course, operating the rudder automatically. The autopilot device is linked to a gyrocompass, which determines direction. For more information on how ships are navigated, see Navigation.

No ship is completely automated. The engine room contains the most automated devices. When the officer on the bridge signals the engines to go ahead or backward or to change speed, the engineer no longer has to make adjustments by hand. Instead, the engines respond immediately and automatically. Most large ships also use electronic navigation aids and automatic devices to speed up the loading and unloading of cargo. Such devices may one day make it possible for large cargo ships to have fewer than a dozen crew members.

Safety.

Safety standards for ships have been set up by International Safety of Life at Sea conventions, which were held in 1914, 1929, 1948, 1960, and 1974. All the major maritime nations have agreed to these standards. The standards require that ships have watertight bulkheads, fire-fighting equipment, and sufficient lifeboats, life jackets, and other lifesaving equipment. Other rules require that lifesaving and fire drills be carried out at regular intervals. In addition, ships must follow the International Rules of the Road. These rules deal with such points as the rights of way of ships on the high seas, the lights ships must show, and the signals that ships must give in fog and during times of distress.

In addition to international maritime laws, individual countries enforce regulations governing the construction and operation of their own ships. The United States has especially high safety requirements. In many cases, its standards are far higher than international rules require. These strict standards have made American ships exceptionally safe. They have also made U.S. ships much more costly to build and operate than foreign ships.

The U.S. Coast Guard ensures that American vessels meet the standards set by the federal government. The Coast Guard must approve the construction plans for each new ship. It inspects ships during construction to make sure that they are being built according to the plans. At regular intervals, the Coast Guard also checks all merchant ships in active service to make sure that they meet all safety regulations. Other developed countries enforce similar standards.

Flags and registration.

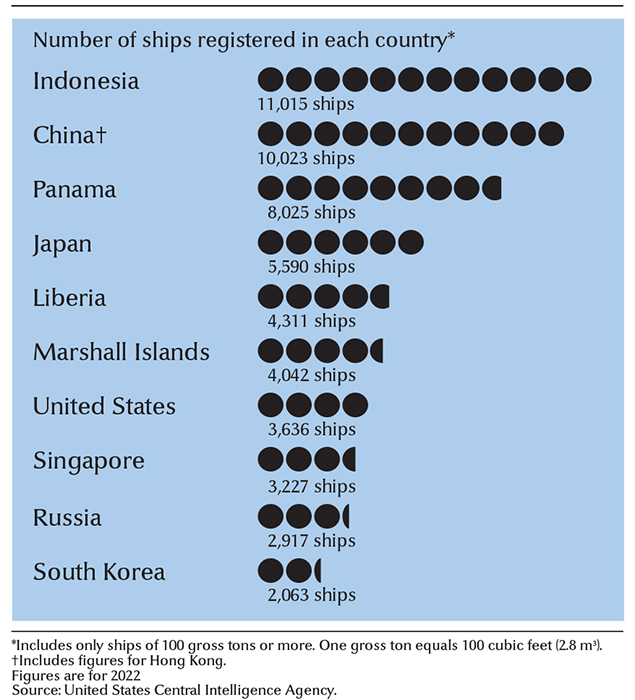

Altogether, the countries of the world have about 100,000 merchant ships of at least 100 gross tons. The world’s merchant vessels total about 1 1/2 billion gross tons. A gross ton is a measure of carrying capacity, equal to 100 cubic feet (2.8 cubic meters) of space. Each year, millions of gross tons of new ships are built. China, Japan, and South Korea produce most of the total gross tonnage of ships launched annually.

In the United States and a number of other countries, many companies register their ships under the flag of another nation. This enables them to operate their vessels with lower-paid crews, to avoid strict safety regulations, and to pay lower taxes than they would by registering in their own countries. A number of nations allow their flag to be used in this way—as a flag of convenience—for a registration fee. Countries that have a flag of convenience include Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Cyprus, Honduras, Liberia, the Marshall Islands, and Panama.

The United States merchant marine

consists of thousands of vessels, including those that sail the Great Lakes and other inland waterways. All of these vessels are registered in the United States and fly the American flag. The size of the United States merchant fleet and the fleets of other maritime nations varies according to the volume of world trade. In addition, many United States merchant ships are inactive or past the age of active use. The United States is one of the chief trading countries in the world. Yet ships flying the American flag carry only a small fraction of the country’s foreign trade.

The federal government requires that all merchant ships registered under the United States flag must be American-built and operated by American crews. But building and operating ships costs at least 50 percent more in the United States than in the lowest-cost shipyards, located mainly in Asia. American-flag ships can thus compete against foreign vessels only with the help of subsidies (grants of money) from the government. The government provides subsidies because it believes that a merchant fleet is vital to the country’s foreign trade and national defense. For example, without a merchant marine, the nation would be completely dependent on foreign shipping lines—which owe no allegiance to the United States—to carry American trade. During wartime, U.S. cargo ships are needed to carry supplies, and shipyards in the United States must be ready to build warships.

Under the Merchant Marine Act of 1936, the Maritime Administration has control over subsidized shipping lines. The act requires that such lines provide regular service on trade routes that the administration selects as essential to United States foreign trade and defense. Subsidized operators must also replace ships that the administration considers too old and inefficient for service.

Many American ship operators prefer not to accept government subsidies. Instead, they buy their ships from foreign shipyards for less than American-built vessels. They then register the ships in a country that has a flag of convenience.

Merchant fleets of other countries.

Many countries have a long tradition as seafaring nations. They include Denmark, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In addition, Japan and a number of other nations have developed large fleets of ships.

China, Indonesia, Japan, Liberia, and Panama have some of the world’s largest merchant fleets. Liberia and Panama allow their flags to be used as flags of convenience. Companies based in other countries own almost all the ships of the Liberian and Panamanian fleets.

Building a ship

Before naval architects begin to design a ship for a shipping company, they must know the firm’s budget and how the firm plans to use the vessel. They must know where the ship will sail, what kind of cargo it will carry, and how fast it will have to travel. Architects also must be aware of government safety regulations. In addition, they must adjust their designs to allow for the ever-increasing use of automation on ships.

Construction.

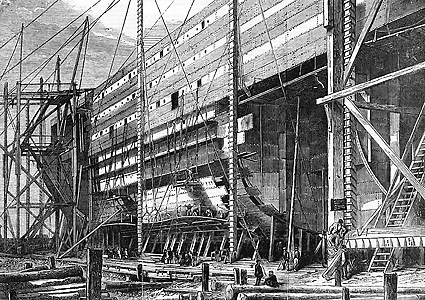

The shipyard carefully follows the architect’s designs in building a ship. Traditionally, construction began with the laying of the keel. Workers then built the ribs that supported the hull and gave it shape. Next, they welded the metal plates that formed the middle section of the hull. As the middle section was built, the various compartments, the boilers, and the necessary machinery were added. Finally, the bow and stern were built, completing the hull.

Modern shipyards first build enormous prefabricated sections of the ship in subassembly shops. Many of these sections have some wiring and piping built into them. Giant cranes then carry these huge sections to a framework called a shipway, where they are welded together. There is no laying of the keel. As the double-bottom sections of the hull are welded together, the keel is laid automatically. The entire hull may consist of as few as 20 prefabricated units. After the hull is completed, parts of the superstructure are added. The ship is then ready to be launched.

Launching and outfitting.

Shipbuilders can launch a ship when construction is about 70 to 90 percent complete and it can safely float. The ship is slid down a runway of heavily greased timbers into the water. Most ships are launched stern first. A ship launched bow first would plow down into the mud. Ships built along rivers too narrow for stern launching are launched sideways.

Some yards build their ships in closed dry docks built below the water level. After the hull and superstructure are completed, workers open valves and flood the dock. The ship then gently floats off the blocks that support the bottom of the hull. After the water inside the dock reaches the level of the water outside it, the dock gate is opened and the ship is launched.

Just before a ship is launched, it is commonly christened (named). The owner selects a person, often a woman, as the ship’s sponsor. This person names the vessel and breaks a bottle of champagne or another drink across its bow. At that instant—if everything is prepared correctly—the ship begins to slide into the water.

After a ship has been launched, a tug pulls it to an outfitting pier. There, workers complete the superstructure and add the interior furnishings. The ship then makes its builder’s trials with observers aboard from the company that ordered the ship. They make sure that all the equipment is in good working order and that the ship performs maneuvering, speed, and other tests according to the contract specifications. If the ship returns from the trials with a broom tied to the mainmast or its highest point, it has made a “clean sweep” of its tests and the shipping company has agreed to accept delivery of the vessel.

Ships and the environment

Ships form important connections among many of the world’s great cities. But the widespread use of ships has damaged the world’s oceans, lakes, and coasts. In connecting distant parts of the world, ships have also led to problems by introducing plants and animals to new areas. Modern ships are designed and regulated in a variety of ways to minimize damage to the environment.

Pollution.

Ships create various forms of pollution in their normal operation. Most modern ships burn fossil fuels—usually oil—to power their motion. The burning of fossil fuels releases air pollution, causing such problems as acid rain. Gases released from ship engines also contribute to global warming. Global warming is an increase in Earth’s average surface temperature. Such greenhouse gases trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere, much as heat is trapped by the walls of a glass greenhouse.

Ships also pump certain types of wastewater into the ocean and other waters. This wastewater may contain detergents, antibiotics, medical waste, disease-causing organisms, and other pollutants and dangerous materials. Oil spills are perhaps the greatest pollution risk from ships. Large oil tankers may carry millions of gallons or liters of oil. A collision with a reef, a sandbar, a coast, or another ship can pierce a tanker’s hull, causing oil to gush out. Oil spills can cause lasting damage to bodies of water and coastal environments, poisoning and killing many living things. Such spills are often extremely difficult and expensive to clean up.

Invasive species.

Ships can be a means of spreading invasive species. Invasive species are nonnative organisms that can spread out of control, harming environments where they are introduced. One of the most prominent invasive species in North America is the zebra mussel, a type of shellfish. Scientists believe the zebra mussel was brought from Europe to the United States in the ballast water of a cargo vessel. Once deposited in the Great Lakes, the zebra mussel thrived. It had no natural predators in its new environment, and so its population soon grew out of control. Today zebra mussels are so numerous that they can clog important waterways and choke out other aquatic life. Many other invasive species have hitched rides on ships over the centuries. Other invasive species have been brought to new places on purpose by people on ships.

Environmental controls.

Modern ships make use of a number of environmental controls. All modern oil tankers must have double hulls. This feature helps protect their cargo from spillage if the outer hull is breached. International regulations prohibit the pumping of wastewater and other potentially toxic substances at sea. Instead, wastewater must be pumped out of ships at a land terminal. There, the liquid can be treated and cleaned for recirculation. Ships in inland waterways must have experienced pilots. They must also move slowly so that riverbanks are not eroded by their wakes.

History

Most early communities throughout the world formed along inland waterways or by coastal waterways with a nearby source of fresh water. Such settlements came to rely on ships and boats. They used these vessels for swift and efficient travel, trade, exploration and colonization, communication, fishing, and many other essential activities.

As cities and towns grew, the ship continued to influence shoreside communities. Ships required timber, sailcloth, hardware and fittings, chests and barrels for food and water storage, and thus the industries associated with these items. Ships also needed shipbuilders, crews, and markets for their supplies. Thus, even people far inland came to be influenced by the development of ships.

The basic pattern for ships was established in ancient times with the invention of the sail and then of the vessel built from wood planks. For about the next 5,000 years, shipbuilders concentrated on designing bigger and bigger ships and on improving the design of the _rig—_the sails with their masts and ropes. Ancient shipbuilders succeeded in building ever-larger ships, but they made little progress with the rig. Big improvements in the rig began during the 1400’s. They reached a high point with the development of the great sailing ships of the mid-1800’s. Steam engines led to even more drastic changes in ship design.

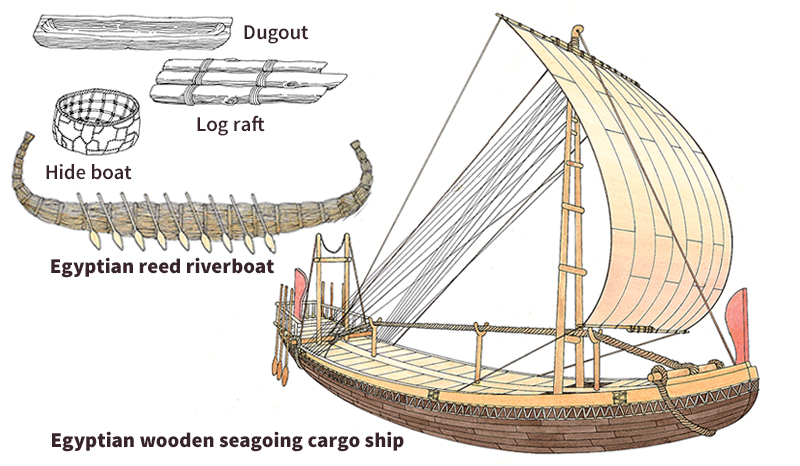

Early watercraft.

The first watercraft was probably a log that was paddled across a lake or river. People likely used their hands as paddles at first. Later, people learned to build rafts by lashing logs together. In time, they discovered how to make dugouts and bark canoes out of large trees. Where wood was scarce, early people made boats of other materials. For example, they sewed animal skins into a bag, which they then inflated and used as a float. Several floats tied together could support a raft. In some areas, the people found that little clay pots tied together could hold up a raft. They also learned that a large pot could serve as a boat for one person, or as a float for a raft.

The oldest evidence for seafaring consists of a number of extremely old stone axes found on the island of Crete, near Greece. The axes date from around 130,000 B.C. Crete has never been connected by land to the mainland in all the time that human beings have existed. So people must have somehow crossed the sea to Crete. Scientists are not sure what kind of vessel the ancient sailors used. But the long journey required to get to Crete suggests a relatively sophisticated vessel.

Egyptian ships.

The ancient Egyptians and other nearby peoples learned to lash bundles of reeds together to make boats with spoonlike shapes. By about 4000 B.C., they had learned to build long, narrow boats powered by rows of oarsmen. During the next 1,000 years, the Egyptians made two more great advances in the development of ships. By about 3000 B.C., they had discovered that sails could harness the power of the wind to propel their boats. In addition, the Egyptians had learned to build boats out of planks of wood. Once people knew how to make plank boats, they could build ships large enough to cross the seas.

The ancient Egyptians designed many kinds of vessels. These included small, graceful canoes, beautiful yachts, and heavy freighters. Their most outstanding shipbuilding achievement was probably the huge barges that carried enormous stone pillars called obelisks up the Nile River from quarries. The biggest barges measured more than 200 feet (60 meters) long and carried 750 tons (680 metric tons) of cargo.

A single sail along with a line of oarsmen on each side of the vessel propelled the yachts and other light Egyptian vessels. The heavier craft were driven by only a sail. The Egyptians used a rectangular sail, called a square sail. At first, they made the sail tall and narrow. But after 2000 B.C., they made it much wider than it was tall. The Egyptians steered their ships with large oars on each side near the stern.

The Egyptians built their vessels chiefly for use on the Nile River. As a result, they made all their craft—even ships used on the sea—rather light. Today, wooden boats are constructed by first making a skeleton of the keel and ribs and then fastening the planks of the hull to the ribs. But the Egyptians built their river craft without a keel or ribs. They simply fitted the planks together by means of joints to form the hull. These vessels were sturdy enough to sail on the Nile, but they were too lightly built for the rougher Mediterranean Sea.

The Egyptian seagoing ships probably had some kind of keel and a few ribs. But the bow and stern of these ships tended to droop, especially in rough seas. So the Egyptians wound a heavy rope around the bow, stretched it tightly across the deck, and looped it around the stern. The rope strengthened the vessels and kept the bow and stern from sagging. The Egyptians sailed chiefly on the Red Sea and along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean.

Minoan and Mycenean ships.

The Minoans, who lived on the island of Crete, became the first major seafaring power of the Mediterranean region. As early as 2500 B.C., their ships ranged the eastern Mediterranean and as far west as the island of Sicily. About 1450 B.C., the Mycenaeans, who lived on what is now the Greek mainland, won control of the sea. The Minoans and Mycenaeans both helped develop the seagoing sailing ship. However, historians know little about their ships. All they know for sure is that these peoples built cargo vessels that were sturdy and roomy and had one square sail.

Phoenician and Greek ships.

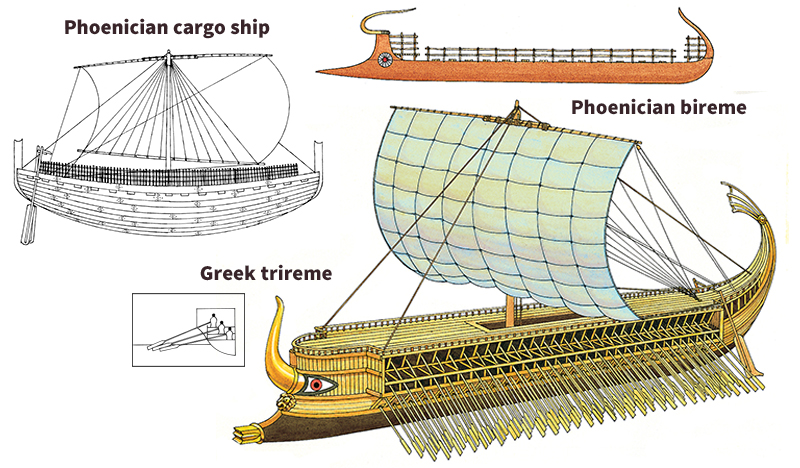

Scholars know much more about the ships used on the Mediterranean Sea after about 800 B.C. At that time, the leading seafaring peoples were the Phoenicians, who lived along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean, and the Greeks.

The Phoenicians and Greeks built broad, roomy cargo ships and greatly improved the ship rig. By about 600 B.C., they built vessels with two masts. The second mast supported a square sail that made steering easier. After 300 B.C., the Greeks set a triangular sail above the mainsail for greater speed. On their biggest ships, they added another square sail near the stern.

This simple four-sail rig was the most advanced rig ever developed by the peoples of ancient times. Ancient ships were slow and could travel at an average speed of only about 5 knots with the wind. The standard Greek freighter measured about 100 feet (30 meters) long and could carry 100 to 200 tons (90 to 180 metric tons) of cargo.

The Phoenicians and Greeks used long narrow ships called galleys for warships. Their galleys were driven by oars. After 1000 B.C., a large, sharp ram (point) was added to the prow at the water line for use in battle. By about 700 B.C., the Phoenicians built galleys with two banks (rows) of oarsmen on each side. The Greeks adopted these ships and made them lighter and faster. By about 500 B.C., the Greeks developed a type of ship called the trieres, which the Romans later called the trireme. It had three banks of rowers on each side.

The Greeks—and later the Romans—built the shell of their ships first, as the Egyptians had done. But they used more and tighter joints to fit the planks together. The planks were held together with slots and pinned pegs. The Greeks and Romans also inserted a system of ribs to stiffen the hull. As a result, their seagoing cargo ships had strong hulls.

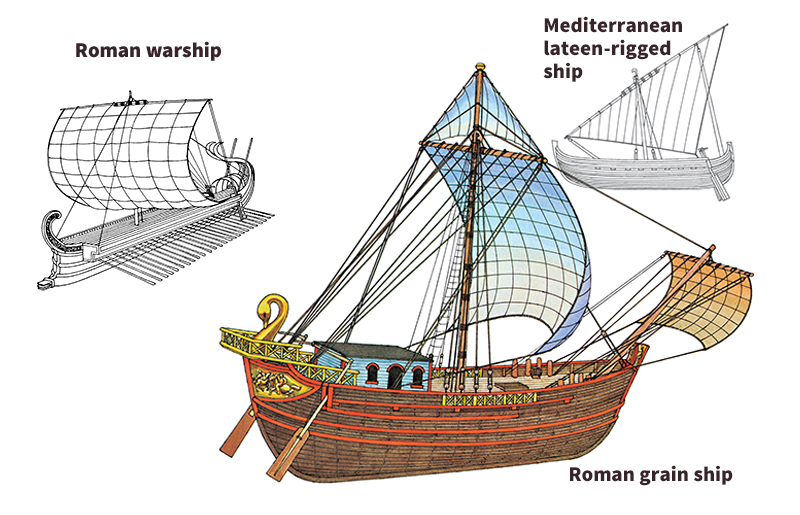

Roman ships.

The Romans became rulers of the Mediterranean region during the 100’s B.C. They used chiefly the same kinds of ships the Greeks had used.

The Romans built up the largest merchant fleet of ancient times. Their biggest cargo ships carried grain from Alexandria, Egypt, to Rome. The largest ones measured up to 180 feet (55 meters) long and 45 feet (14 meters) wide. They could haul more than 1,000 tons (900 metric tons) of cargo and more than 100 passengers.

Roman cargo ships, like all freighters of ancient times, carried travelers. There were no ships designed only for passengers. Travelers simply reserved space on any freighter going their way. The ships had a few cabins for important people. The other passengers stayed on the open deck.

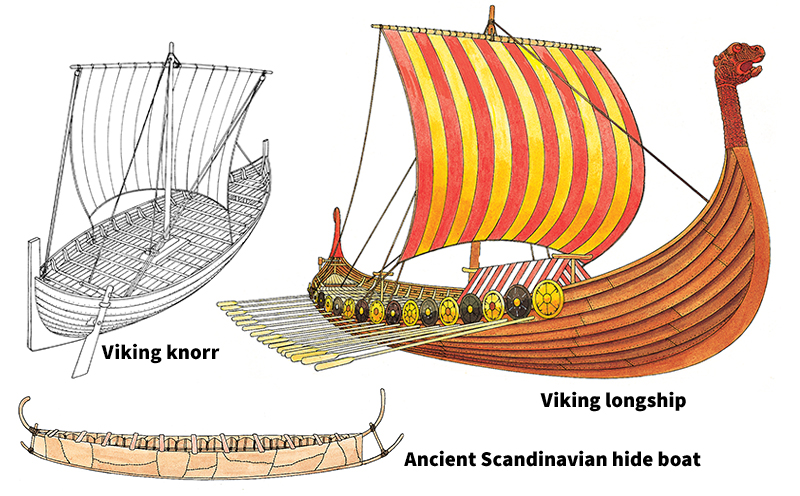

Viking ships

were the best seagoing vessels built in northern Europe between the A.D. 700’s and the late 1000’s. The Vikings sailed their famous longships across the North Atlantic Ocean to Greenland and even to North America. They raided, traded, and colonized. As fast-striking pirates, they were the terror of the seas.

Scholars know much about the superb Viking ships because many Viking lords arranged to be buried in their boats. Scientists have found several such tombs. A well-preserved example of a Viking warship was uncovered in 1880 near Gokstad, in southeastern Norway. The Vikings built the ship about A.D. 900. It measures 78 feet (24 meters) long and about 17 feet (5 meters) wide. As with all Viking ships, the hull is _clinker-built—_that is, the planks overlap like siding on a house. The ship carried 16 oarsmen on each side. It had a square sail mounted on a mast probably 40 feet (12 meters) high and a steering oar near the stern. The Gokstad ship was relatively small. Most vessels had 20 oars on each side, and some had 30. See Vikings (Shipbuilding and navigation).

In 1893, a group of Norwegians built a full-scale replica of the Gokstad ship. They sailed it across the Atlantic Ocean from Bergen, Norway, to St. John’s, Newfoundland, in only 28 days, in spite of bad weather.

The cog.

The power of the Vikings gradually declined. By the late 1000’s, they had lost control of the northern seas. Trade then began to increase among the countries of northern Europe. Merchants needed roomier vessels to carry larger shipments. By about 1200, shipbuilders in the north had developed a sturdy ship called the cog. It became the standard merchant vessel and warship of northern Europe for about 200 years.

Cogs could stand up against the rough seas and high winds of the North Atlantic Ocean. Their deep, wide, clinker-built hulls could hold bulky cargoes. These ships had one large square sail. They also had a high structure called a castle at the bow and the stern. The forecastle, at the bow, served as a platform from which marines could fire arrows and stones at enemy ships. The sterncastle provided a shelter for important passengers. Cogs also featured a new kind of steering apparatus. Instead of steering oars along the sides near the stern, cogs had a large rudder in the stern’s middle. The rudder, introduced by about 1200, could steer more strongly than could oars.

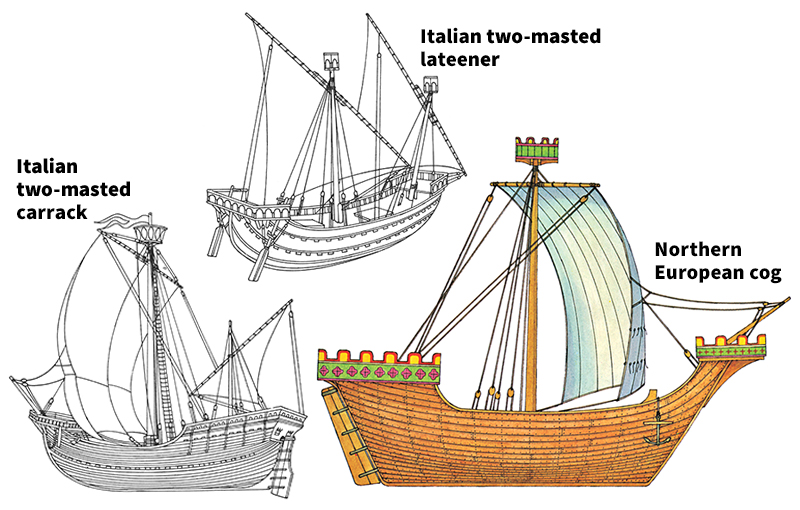

Lateen-rigged ships.

While northern shipbuilders were developing the cog, Mediterranean shipbuilders were also making important changes in ship construction and design. Around 1100 A.D., Mediterranean shipbuilders began a new way of shipbuilding that became standard. They built a skeleton of keel and ribs first and then fastened the planks of the hull to the framework. They also greatly increased the use of triangular sails called lateens. Square sails worked well with winds blowing from behind. But unlike lateen sails, they did not work well when sailing into the wind.

Galleys had always been used in the Mediterranean region as cargo and passenger ships as well as warships. But about 1300, the use of cargo and merchant galleys increased greatly. These galleys generally used their oars only when there was no wind and when entering or leaving a harbor. The rest of the time, the vessels were driven by lateen sails. Most galleys had two masts, with the forward mast carrying the large sail. Some had three masts. The merchant galleys were longer and wider than the warships. The standard galley could carry about 140 tons (130 metric tons).

The full-rigged ship.

About the mid-1400’s, Mediterranean shipbuilders combined the best features of the sturdy cog with those of their own lighter lateen-rigged vessels. The result was a sailing ship that became standard throughout Europe for about 300 years. The Mediterranean shipbuilders continued to build the hull frame first. But they replaced the steering oars with a rudder centered under the stern. They also adopted the forecastle and sterncastle of the cog. Most important, they changed the rig to gain more power and better maneuverability—and so developed the full-rigged ship.

The basic full-rigged ship, or square-rigger, had a mainmast in the middle of the ship, a foremast in the forward part, and a mizzenmast in the back part. The mainmast and foremast each carried a big square sail and, above it, a smaller square sail. The mizzenmast held a lateen sail. A pole that stuck out from the bow carried a small square sail. During the late 1400’s and 1500’s, such explorers as Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Sir Francis Drake, and Ferdinand Magellan used ships rigged in this way.

The new three-masted ships were relatively small and had few comforts. Only the captain, other high-ranking officers, and guests had cabins. The rest of the crew slept on the deck or in hammocks below deck. The hammock was an American Indian invention that Columbus brought back to Europe.

Chinese ships.

Around the same time, Chinese mariners engaged in much exploration and trade around the Indian Ocean. The most famous Chinese mariner was Zheng He. He commanded seven large naval expeditions from 1405 to 1433. Sent by the emperor of China’s Ming dynasty, Admiral Zheng’s mission involved establishing a Chinese presence in the region, seeking new trade opportunities, and suppressing piracy. Zheng had a large fleet of naval and cargo vessels, along with a large army. He distributed Chinese luxury items as diplomatic gifts and returned home to China with exotic animals and other novelties.

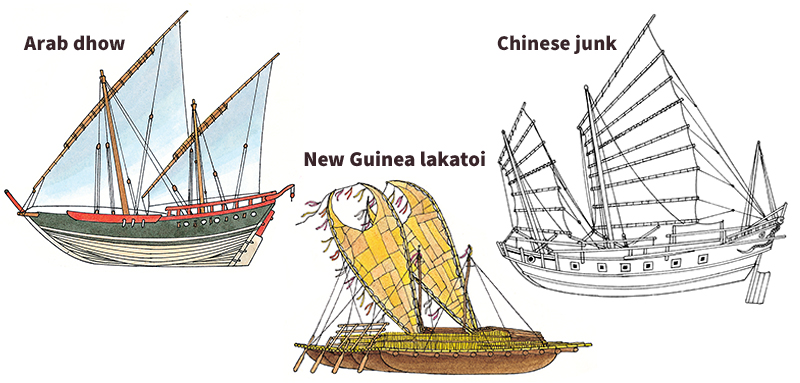

Zheng’s biggest and most powerful ships were junks, a longstanding Chinese ship design. His junks had watertight bulkheads, multiple masts, and stern rudders. The sails ran parallel to the length of the ship. A similar type of ship is still in use today along China’s coasts and inland waterways.

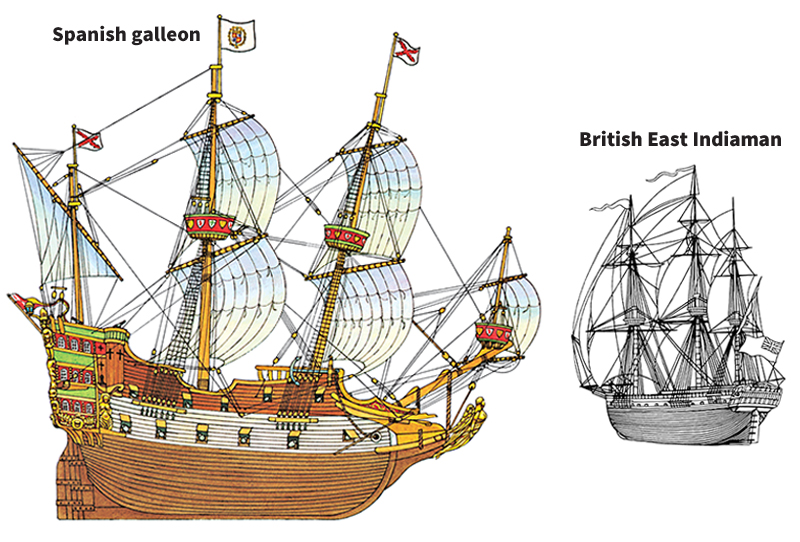

The galleon.

About the mid-1500’s, a type of sailing ship called the galleon appeared on the seas. Galleons were big vessels with a low forecastle and a high sterncastle that housed elaborate living quarters. The foremast and mainmast each carried two or three sails, and the mizzenmast carried one or two. On the biggest galleons, a second mizzenmast was added near the stern.

Galleons served as both warships and cargo vessels. Guns had been used aboard ships since about the mid-1300’s. But galleons carried more and heavier guns. In 1588, the English and Spanish fleets fought one of the most famous sea battles in history. Both sides used galleons. But the English galleons were faster, more maneuverable, and better armed. They helped defeat the Spanish fleet. The Spaniards had called their fleet the Invincible Armada because they thought it could not be defeated (see Spanish Armada).

Spain, Portugal, and other countries also used armed galleons for trading. Spanish sailors brought back gold and silver from the New World on galleons. These treasure ships became a favorite target of pirates who roved the Caribbean Sea.

East Indiamen.

For centuries, ships had served as both cargo vessels and warships. But by about the 1600’s, cannons had become so heavy that ships needed heavily built hulls to carry the added weight. The design of warships and that of unarmed cargo vessels thus diverged greatly by the 1700’s.

In the 1600’s, trading companies in several European countries began to build merchant ships especially for trade with India and the Far East. These ships brought ivory, silks, spices, and other products from India, China, and the East Indies. The Portuguese controlled the trade with the Far East until about 1600, when England and the Netherlands began to compete. Then Denmark and France also entered competition. East India companies in each country built their own ships, called East Indiamen. Although the Indiamen were designed as cargo carriers, they carried guns for defense against attack by pirates and by the fleets of enemy countries.

The design of the East Indiamen grew steadily larger in size. In 1700, for example, most English Indiamen carried 400 tons (360 metric tons) of cargo. By 1800, they carried 1,200 tons (1,100 metric tons).

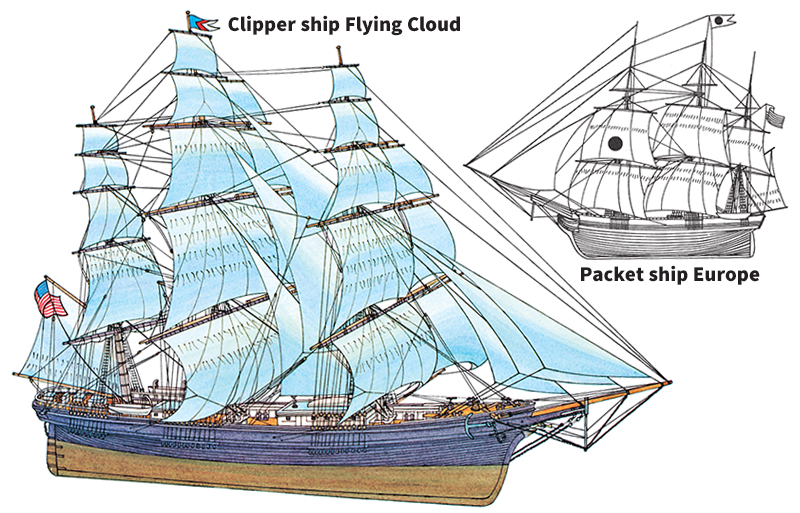

Packet ships.

By the early 1800’s, trade between the United States and European countries had increased tremendously. Also, a great demand had developed for improved transatlantic passenger service. American shipowners met the demand by offering a new service—ships that sailed on regular schedules. Such vessels were called packet ships, named for the mail packets they carried in addition to other cargo and passengers. Government payments for the mail packets helped finance the ships’ voyages. Before this time, ships sailed only if they had a full load of cargo and passengers. Also, the weather generally had to be favorable. Packet ships sailed at a scheduled time, fully loaded or not and regardless of the weather. Packet ships also became the first merchant vessels to stress the comfort of passengers. Packet service began in 1818, between New York City and Liverpool. The Black Ball Line started the service. It was so successful that other U.S. lines, such as Red Star and Swallowtail, quickly followed.

To meet schedules and best their competition, packet ships had to sail as fast as possible. But the ships themselves were ordinary sailing vessels that had not been designed with especially sharp lines for speed. The speed came from their captains, who drove the ships hard night and day in all weather. The eastward Atlantic crossing took from three to four weeks. The westward crossing took longer, from five to six weeks, because the ships had to sail against the currents and westerly winds along a longer, more southerly route.

The first packet ships measured about 100 feet (30 meters) long. By the 1840’s, as passenger accommodations became larger and more comfortable, ships 160 feet (50 meters) long had come into use.

Clipper ships,

considered by many to be the most beautiful and romantic of all sailing ships, dominated the seas during the mid-1800’s. The clippers, with their slender hulls and many sails, were designed for speed. Their name came from the way the ships “clipped off” the miles.

The United States built the first true clippers in the 1840’s. They were designed to sail from the East Coast, around the tip of South America, to China and to bring back tea. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 and in Australia in 1851 hastened the clipper’s development, as fortune seekers and supplies were rushed to the gold fields. The ship’s success led the British to build a fleet to carry tea from China and wool from Australia.

Clippers had as many as six levels of sails to a mast. Some ships had as many as 35 sails. Driven at top speed, clippers could cut through the water at 20 knots. Many could race from New York City, around South America, to San Francisco in less than 100 days. But they needed large crews of up to 100 men to achieve these speeds.

Donald McKay, a Canadian, became the greatest designer of clipper ships. His shipyard in East Boston, Massachusetts, turned out over 90 of them. McKay’s first clippers measured about 200 feet (60 meters) long and could carry 1,500 tons (1,360 metric tons). He steadily increased the size of his ships. In 1853, he launched the Great Republic, the largest sailing ship of its time. It was about 335 feet (102 meters) long, had four masts, and could carry more than 4,500 tons (4,100 metric tons).

Sailing ships in the 1900’s.

By the early 1900’s, the steamship had nearly replaced the oceangoing sailing ship. But coal-burning steamships needed reliable supplies of coal, and certain trade routes—such as those along the coasts of South America—had few coaling stations. Sailing ships continued to be used on these routes. For many years, for example, sailing ships carried nitrate, a fertilizer, from Chile, around the tip of South America, to Europe.

The sailing ships launched during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s were huge vessels built more for strength than speed. They had strong, straight-sided steel hulls and wire rigging. To operate cheaply, they used small crews and, therefore, carried a minimum amount of sail. The mightiest of these ships was the Preussen, a five-masted, full-rigged German vessel built in 1902. It was the largest sailing ship ever built, measuring 433 feet (132 meters) long and 54 feet (16 meters) wide. It could carry 8,000 tons (7,300 metric tons) of cargo.

Since the early 1900’s, the number of seagoing sailing ships has declined rapidly. Many have rotted, rusted away, or sunk at their docks. Today, most of the few remaining square-riggers serve as museum curiosities, tourist attractions, or training ships for cadets in the navies and merchant marines of various countries.

In many developing countries, people still use smaller sailing vessels for coastal and inland shipping and for fishing. For hundreds of years, Arabs have sailed the Red Sea and Persian Gulf in long, slim, lateen-rigged vessels called dhows. Various Indian versions of the dhow are common along the coastlines and in the harbors of Kolkata, Mumbai, and other port cities of India. The people of New Guinea have long used a sailing vessel called a lakatoi, which consists of several dugouts lashed together. Two-masted sailing ships called schooners carry cargo along the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean. Schooners and single-masted sloops sail between Panama and Ecuador, along South America’s west coast, and in the Caribbean.

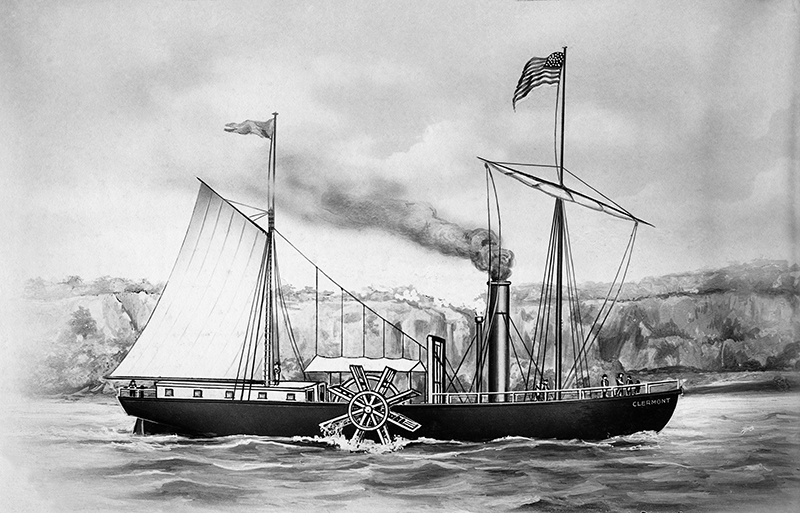

The first steamboats.

The invention and development of the steam engine revolutionized water transportation. People no longer had to depend on the muscles of rowers or the uncertain wind to propel their ships. In 1769, James Watt, a Scottish engineer, patented a steam engine that could do many kinds of work. Inventors in Europe and the United States soon tried to use it to power boats.

In 1783, the Marquis Claude de Jouffroy d’Abbans, a French nobleman, built a steamboat that made a single 15-minute trip on the Saône River near Lyon. In 1787, John Fitch, an American inventor, demonstrated the first workable steamboat in the United States. Its engine powered a series of paddles on each side of the boat. Fitch later developed a vessel pushed by paddles at the stern. With this boat, he started the nation’s first commercial passenger and freight service, during the summer of 1790. He navigated the boat on schedule on the Delaware River between Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Trenton, New Jersey. But Fitch lacked enough money to keep operating. In 1802, William Symington, a British engineer, built a steam tug that had a paddle wheel at the stern. The tug worked perfectly, but Symington also ran out of money.

The Clermont became the first commercially successful steamboat. Robert Fulton, an American, designed and built the vessel, which was officially called The North River Steamboat of Clermont. Fulton did not try to construct an engine himself, as earlier inventors had done. Instead, he ordered one from Watt and adapted it to his boat. In 1807, the Clermont steamed 150 miles (240 kilometers) up the Hudson River from New York City to Albany in about 30 hours, including an overnight stop. After extensive rebuilding, the boat sailed in regular passenger service on the Hudson. The Clermont was long and slender—originally 142 feet (43.3 meters) long and 14 feet (4.3 meters) wide. After the rebuilding, the Clermont was 149 feet (45.4 meters) long and 18 feet (5.5 meters) wide.

Oceangoing steamships.

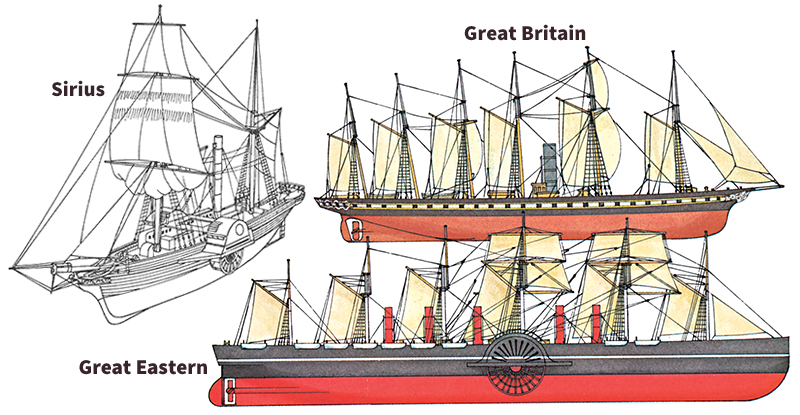

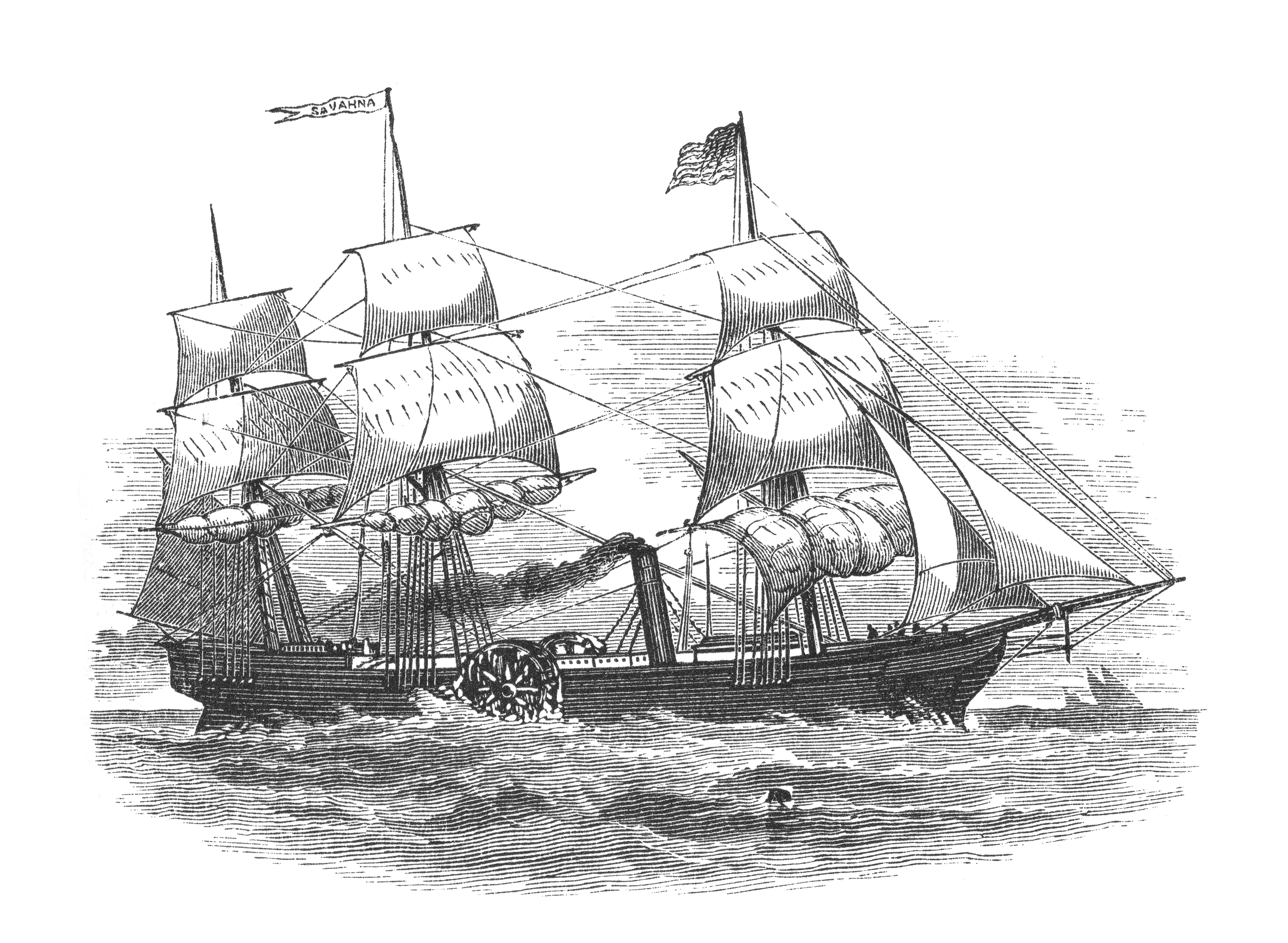

Fulton’s boats puffed along only on bays and rivers. In 1809, the Phoenix became the first steamboat to make an ocean voyage. John Stevens, an American engineer, built it. The Phoenix traveled along the Atlantic Coast and up the Delaware River from New York City to Philadelphia. The trip took 13 days. Under perfect conditions, sailboats could do it in 2 days. In 1819, an American vessel, the Savannah, became the first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean. It was actually a full-rigged sailing ship equipped with steam-powered side paddle wheels. The ship took 29 days to travel from New York City to Liverpool. During the voyage, it ran its engine 105 hours, using up its entire fuel supply of 75 tons (68 metric tons) of coal and 25 cords (91 cubic meters) of wood. In 1838, the British side-wheeler Sirius became the first ship to offer regularly scheduled service across the Atlantic under steam power alone. The trip took 18 1/2 days.

Ships of iron.

During the late 1700’s, British shipbuilders had begun to construct iron vessels, partly because good wood for ships was becoming scarce in the United Kingdom. But iron ships also had many advantages over wooden ones. They were stronger, safer, more economical, and easier to repair. In addition, iron ships were lighter than wooden ships of the same size, because wooden ships required huge, heavy timbers. As a result, iron ships could hold more cargo.

The United Kingdom led the world in the development of iron seagoing ships. In 1821, it launched the Aaron Manby, probably the first all-iron steamship. The United Kingdom’s most gifted naval architect of the mid-1800’s was Isambard Kingdom Brunel. In 1837, he launched the Great Western, the first steamship designed especially for regular Atlantic crossings. The Great Western measured 236 feet (72 meters) long and 35 feet (11 meters) wide. Its huge side wheels drove the vessel at 9 knots. In 1858, Brunel completed the Great Eastern, among the most spectacular ships built by that time. It was 692 feet (211 meters) long and about 85 feet (26 meters) wide and accommodated 4,000 passengers. But the ship failed economically. It did not attract enough customers to pay its huge operating costs. On the other hand, it was used in laying four successful transatlantic telegraph cables across the ocean floor. In 1888, the ship was sold for scrap.

During the late 1800’s, steel began to replace iron for ships. Steel ships were stronger and lighter than iron ones. In 1881, the Servia, a British vessel, became the first all-steel passenger liner to cross the Atlantic.

The first propeller-driven ships.

In 1836, two inventors—Francis Pettit Smith of England and John Ericsson of Sweden—each patented a propeller that could drive steamboats more efficiently than paddle wheels could. The side paddles had worked well in rivers and in calm waters. But in rough seas, as a ship rocked from side to side, one wheel and then the other might stick completely out of the water, wasting power. In addition, waves easily damaged the large, fragile wheels. A ship propeller, wholly under the water at the stern, used power more efficiently than the paddle wheels did. As the propeller bit into the water, it also pushed the ship forward much faster. In 1845, the Great Britain, designed by Brunel, became the first propeller-driven ship to travel across the Atlantic.

Stronger, faster ships.

New types of engines and new sources of power were developed as ships began using steel materials and propellers. Until the middle to late 1800’s, ships used steam engines with a single cylinder. The steam expanded in the cylinder, drove the piston a full stroke, and then passed to a condenser, where it was converted back to water. By the late 1800’s, the compound steam engine, which had two cylinders, began to be used on ships. In the compound engine, steam pushed the piston in one cylinder and then passed on to a second, larger cylinder. The engine thus created much more power from the same amount of steam. The compound steam engine cut the use of coal on ships up to 50 percent. Later, shipbuilders installed three-, four-, and five-cylinder steam engines on their ships.

In the 1890’s, Charles A. Parsons, an English engineer, designed a marine steam turbine, a completely new type of marine engine. It was much more powerful and efficient than the steam engine. In 1897, Parsons installed three turbines in his vessel, the Turbinia. The turbines powered the vessel at a speedy 34 1/2 knots. Within a few years, fast luxury liners powered by steam turbines began crossing the Atlantic Ocean. One of the most famous of these passenger liners was the British ship Mauretania, launched in 1907. It was 790 feet (241 meters) long and had a speed of 27 knots.

While Parsons was working on his steam turbine during the 1890’s, Rudolf Diesel, a German mechanical engineer, was perfecting another new type of engine. It used heavy oil as fuel. His engine, now called the diesel engine, used less fuel than the turbine and required much less space on a ship. In 1910 and 1911, the first diesel-powered ships, which are called motorships, went into operation. Beginning about 1920, oil also began to replace coal as fuel for steam turbines. Today, most steamships use oil.

Passenger vessels.

Two British firms—the Cunard Line and the White Star Line—dominated transatlantic passenger service until about 1900. Then, Germany’s North German Lloyd Line and Hamburg American Line began to offer serious competition. Later, French and Dutch lines entered the race for transatlantic passenger business. Much of this business came from transporting immigrants from Europe to the United States. The United States took the lead in providing service across the Pacific Ocean with the founding of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company in 1848. As various shipping lines competed for passengers, ships became larger, faster, and more luxurious.

The great age of the ocean liner came in the early 1900’s. It reached its height in the 1930’s with the launching of three of the most luxurious ships ever built. They were the Normandie of France and the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth of the United Kingdom. These giants, each almost 1,000 feet (300 meters) long, crossed the Atlantic Ocean in just over four days. During the 1960’s, the United Kingdom sold the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth to American investors who planned to make tourist attractions of the ships.

Beginning in the late 1940’s, the airplane began to attract more and more transoceanic passengers. Today, jet planes fly daily between the world’s great cities. They cross the sea in hours, not days, and at about half the cost of an ocean trip. Most ocean liners cannot compete with the airplane and have given up. In 1952, American shipbuilders launched the United States, the pride of the nation’s passenger fleet. The United States had a cruising speed of 33 knots and was the fastest ocean liner afloat—it was possible to water-ski behind the ship. But in 1969, the ship stopped operating because of a lack of passengers. Today, the United States has no major passenger liner service across the Atlantic.

Nuclear power and automation.

In 1954, the United States launched the world’s first nuclear-powered ship, the submarine Nautilus. It was retired in 1979. In 1959, the U.S. launched the Savannah, the first nuclear-powered merchant ship. It was retired in 1971. Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union also built nuclear-powered merchant ships. But the only nuclear merchant vessels today are a small number of Russian icebreakers. Nuclear reactors are impractical for other commercial ships because of the high cost of building and operating them.

Ships today have become increasingly automated. On many modern steamships, for example, electronic equipment controls the flow of fuel oil and air to the furnace and of water to the boilers. Automatic navigation aids help keep ships on course. Ships have also become larger and larger. They are often designed to maximize space for a certain type of cargo and to speed loading and unloading.

Modern society, like past societies, depends heavily on ships—although today most larger vessels operate largely outside public view. Giant tankers transport the petroleum products that fuel automobiles and heat people’s homes. Large factory trawlers catch, process, freeze, and transport much of the fish available at stores and restaurants. Giant car carriers move cars and trucks around the world from factories to consumers. Colossal container ships transport clothing, electronics, manufactured goods, and other products around the world swiftly and securely.