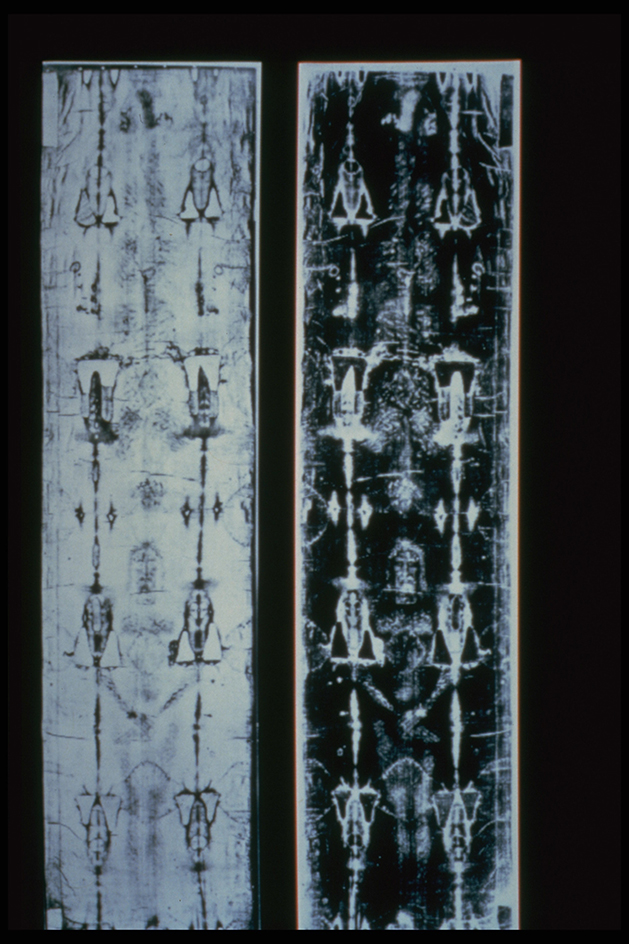

Shroud of Turin, << TOO rihn, >> is a linen cloth that many scholars and scientists believe was the burial cloth of Jesus Christ. The cloth measures about 14 feet 6 inches by 3 feet 8 inches (442 by 113 centimeters). It bears a faint image of the front and back of a man who was whipped, crowned with thorns, and crucified. Wounds on the image follow the details of the death of Jesus as described in the Bible. The shroud is kept in St. John the Baptist Cathedral in Turin, Italy.

Many people believe the shroud is actually a cloth called the Mandylion of Edessa (now Urfa, Turkey), first documented about A.D. 400 as a painting of Jesus’s face. In the 500’s, a Christian writing called the Acts of Thaddaeus described the image as miraculously made on a large folded cloth. The Mandylion was taken to Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) in 944. The present shroud face resembles early artists’ copies made during the 900’s of the Mandylion image. Eyewitness texts described the image as that of a bloodstained body on a burial shroud. The shroud was documented often in Constantinople. It disappeared in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade.

The shroud reemerged in the early 1350’s in Lirey, in northeastern France, in the possession of a French knight named Geoffrey de Charney. In 1453, the Savoys, the future royal family of Italy, acquired the cloth from the Charneys. The Savoys took it to Chambery, in southeastern France, where it was damaged in a fire in 1532. Saint Charles Borromeo, cardinal-archbishop of Milan, announced that he would travel across the Alps to Chambery specifically to view the Shroud of Jesus. Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, had the shroud sent to Turin to save Charles the ordeal of crossing the Alps. The Savoys decided to take up their chief residence in Turin, and the shroud never returned to Chambery.

The shroud’s authenticity has often been challenged. About 1389, a French bishop condemned it as a painted forgery. In 1898, the first photographs of the shroud cast doubt on the bishop’s claim. The negatives of the photos showed a positive image more natural and more detailed than the faint image on the shroud. According to experts, no ancient or medieval artist could have created such an image. Modern attempts to re-create all the subtleties of the shroud’s image by scientific or artistic means have failed.

From the 1970’s through the 1990’s, scientists performed many tests on shroud material. In 1978, after extensive testing of the cloth, a team of scientists stated that the shroud contains real bloodstains and the image was not the work of an artist. However, the team concluded that the cause of the image remains unknown.

In 1988, radiocarbon dating of cloth from the shroud placed its date between 1260 and 1390. In 2005, this dating was questioned when chemical analysis determined that the material used in the test was not taken from the main body of the shroud but from a skillfully rewoven area. Studies of limestone dust and pollen from Palestine found on the cloth supported the shroud’s ancient Middle Eastern origin.

The shroud acquired a new look in 2002 with the removal of the patches and backing cloth attached following the 1532 fire. A balanced discussion of the shroud and its history appears in The Blood and the Shroud (1998) by Ian Wilson.

See also Turin .