Smoking is drawing tobacco smoke from a cigarette, cigar, or pipe into the mouth—and often into the lungs—and puffing it out. The term usually refers to cigarette smoking, the most common form of smoking (see Cigarette).

People have smoked tobacco for thousands of years. Native Americans smoked tobacco in pipes during religious ceremonies long before Europeans came to the New World (see Peace pipe). In the United States, cigarette smoking became popular during the 1900’s. Advances in the manufacture of cigarettes made smoking more affordable, and tobacco companies spent millions of dollars on advertising. Cigarette consumption in the United States rose from an average of 54 cigarettes per person per year in 1900 to 4,148 cigarettes per person per year in 1973. But by the late 1990’s, cigarette consumption had declined to an average of 2,000 cigarettes per person per year. In 1955, research surveys show that about 45 percent of American adults were habitual cigarette smokers. Today, less than 12 percent of all adults in the United States smoke cigarettes.

Nearly all smokers smoke to satisfy a craving for nicotine, a chemical substance that occurs naturally in tobacco and tobacco smoke. Nicotine is a poisonous and highly addictive substance. A typical cigarette contains about 1 to 2 milligrams of nicotine. The chemical affects the nervous system as both a stimulant and a depressant, so smoking can feel both refreshing and relaxing at the same time.

Nicotine interferes with chemicals called neurotransmitters, which carry messages from one nerve cell in the brain to another. Over time, the balance of neurotransmitters in the brain changes as the brain adapts to the nicotine from cigarette smoke. When smokers stop smoking, an imbalance occurs in the brain, giving smokers a feeling of anxiety. The relaxation that smokers usually experience when smoking actually comes from relief of their nicotine craving.

Since the mid-1900’s, scientists have accumulated evidence that smoking is dangerous to a person’s health. In 1964, the United States surgeon general first officially warned that smoking causes lung cancer. Since then, scientists have shown that cigarette smoking causes heart disease, lung disease, and many other health problems. In 1988, the surgeon general concluded that nicotine was an addictive drug. Cigar and pipe smoking and chewing tobacco also lead to nicotine addiction and can cause cancers of the mouth and throat.

In the 2000’s, manufacturers developed new ways of using tobacco or nicotine that do not involve chewing tobacco or burning tobacco to create smoke. Electronic cigarettes, or e-cigarettes, are devices that vaporize a liquid mixture of ingredients. Devices called IQOS << (pronounced EYE kohs) >>, an acronym for I–Quit-Ordinary-Smoking, heat a tobacco stick, producing vapor. This article primarily discusses cigarette smoking. For a discussion of other ways of using tobacco or nicotine, see Electronic cigarette.

Why smoking is dangerous.

Tobacco smoke contains more than 4,000 chemicals, including many carcinogens (substances known to cause cancer). Other chemicals in tobacco smoke coat or dissolve the lining of the lungs and interfere with the normal functioning of blood and blood vessels.

Cigarette smoke contains carbon monoxide, a colorless, odorless gas that reduces the oxygen-carrying ability of red blood cells. Other chemicals found in cigarette smoke include hydrogen cyanide, nitrogen oxides, benzene, and ammonia. The smoke also contains tiny solid particles called tar. These particles contain chemical compounds called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are carcinogens that also damage blood vessels. Cigarette smoke also contains harmful metals such as nickel, zinc, and radioactive polonium 210.

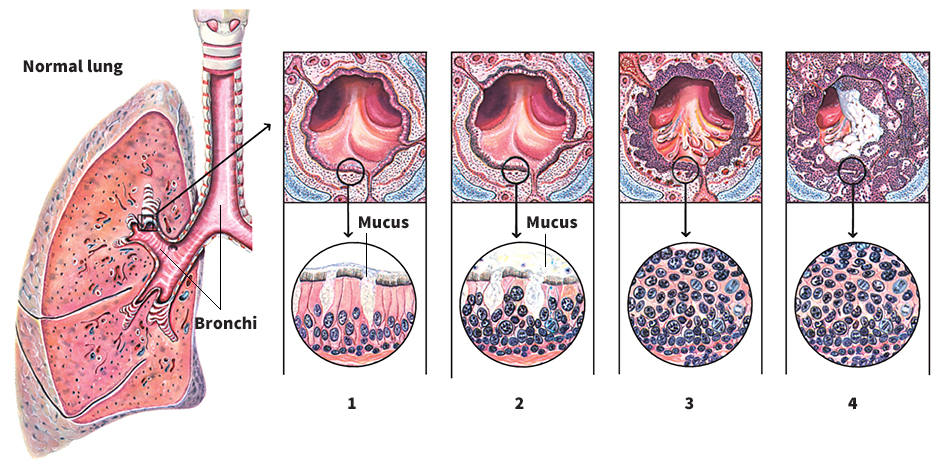

When smokers inhale, hot gases burn the lining of the airways, and the larger tar particles are deposited in the airways leading to the lungs. Over time, the smoke scars the lungs and damages the cilia, thousands of tiny hairs that line airways and keep them clean. The damage increases a smoker’s chances of developing bronchitis, influenza, and other lung infections. The smoke also harms tiny air sacs in the lungs, which can lead to emphysema, a serious lung disease. See Emphysema.

The chemicals in cigarette smoke are absorbed into the blood through the lungs and distributed throughout the body. The chemicals can accumulate in organs, leading to cancer in the kidney, pancreas, bladder, and cervix. Among pregnant smokers, the chemicals reach the developing baby, hindering growth and increasing the chance of spontaneous abortion (miscarriage).

Smoking damages the heart and blood vessels. Cigarette smoke increases the activity of blood platelets, which cause blood to clot. It also reduces the ability of blood vessels to dilate (expand) and contract to adjust blood flow. These changes contribute to artery blockages, which can cause heart attack or stroke.

Secondhand smoke.

Exhaled smoke and smoke from a smoldering cigarette, cigar, or pipe can cause lung cancer and other diseases in nonsmokers exposed to it. Such smoke is called secondhand smoke. Smoke from smoldering tobacco products is especially unhealthful because it does not pass through a cigarette filter or the smoker’s lungs and thus often holds more toxic chemicals than exhaled smoke does.

Secondhand smoke can also cause irritation in the throat and eyes, nausea, and headaches in nonsmokers. Breathing secondhand smoke also damages blood and blood vessels in ways similar to those found in people who smoke. Secondhand smoke around infants increases the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), asthma, and respiratory infections.

How smokers quit.

Breaking nicotine addiction and quitting smoking is difficult. Most people who try to stop return to smoking within a year, and people usually have to try many times before they finally quit.

Most smokers who stop smoking quit on their own, but some benefit from clinics that specialize in helping smokers quit. People sometimes use special chewing gum or skin patches that slowly release nicotine into the bloodstream. These products help many people reduce the nicotine craving that develops as they stop smoking. Living in a smoke-free home or working in a smoke-free workplace usually aids a smoker’s effort to quit.

Smokers who quit experience immediate health benefits. Within a day, blood pressure, heart rate, and the oxygen-carrying capacity of red blood cells return to normal. The risk of heart attack also decreases. Within a week, lung function improves, and the effects of smoking on pregnancy are reduced. Within a year, the cilia return to normal in the lungs, and the risk of heart attack is reduced to about double that of a nonsmoker. About 10 years after a smoker quits, the risk of developing lung cancer is nearly the same as that for a nonsmoker.

Smoking regulations.

Legislation and policies regulating smoking have provided increased protection for nonsmokers and have influenced many smokers to smoke less or quit. A 1964 United States law requires that all packaging and advertising for cigarettes carry a health warning. Federal laws in Canada require health warnings on cigarette packages and restrict advertising. The Canadian government and all U.S. states place age limits on tobacco sales. Hundreds of communities in the United States and other countries have also passed laws that prohibit smoking in workplaces, public places, restaurants, and taverns.

In the early 1990’s, smokers in the United States filed several class action suits, which enable people to sue as a group rather than as individuals. These suits claimed tobacco companies had hidden evidence that nicotine was addictive and manipulated nicotine levels to keep smokers dependent. About the same time, secret tobacco industry documents were leaked to the public. The documents showed that the tobacco industry knew that smoking caused disease and that nicotine was addictive, but kept the information secret.

The newly discovered evidence strengthened a series of lawsuits that several states had brought against the tobacco industry. The lawsuits sought to force the industry to reimburse the states for the costs to taxpayers of treating smoking-related illness. In 1996, one tobacco company, the Liggett Group, agreed to settle some of the suits. By 1998, tobacco companies and all states that had not previously settled their claims reached a broad settlement. In the agreement, the tobacco industry agreed to pay the states a minimum of $206 billion over the next 25 years. The industry also agreed to pay states each year in perpetuity (with no end date). The amount of money paid each year is determined by the smoking population in each state. Many states have used some of the settlement money to fund antismoking programs. The settlement also banned companies from promoting tobacco products to young people.

In 2009, the United States passed legislation that enabled the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to regulate cigarettes and other tobacco products. The law allows the FDA to regulate the amount of nicotine in cigarettes, requires cigarette manufacturers to list ingredients on packages, bans most flavorings added to cigarettes, and severely restricts cigarette advertising. In 2016, the FDA extended its regulatory authority to include e-cigarettes.