Spain is a country in western Europe famous for its colorful bullfights, flamenco music, sunny climate, and beautiful castles. Spain was once a great empire with colonies throughout the world. Spanish language and culture took root and became a part of the culture of many nations. Today, Spain is a prosperous nation with a well-developed economy based on service industries, such as tourism, and on manufacturing.

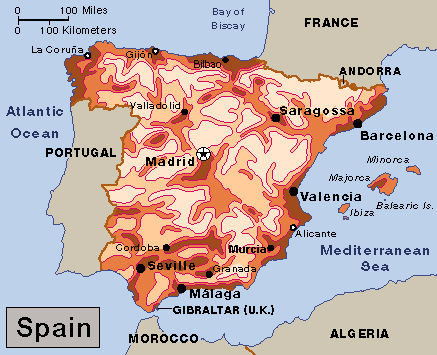

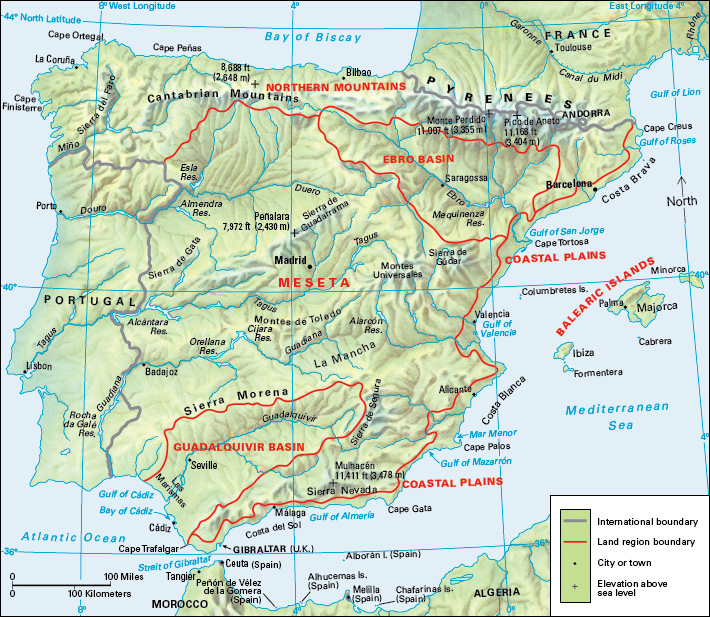

Spain is one of the largest countries in Europe. It occupies about five-sixths of the Iberian Peninsula, which lies in southwestern Europe between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Portugal occupies the rest of the peninsula. Spain also includes the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea and the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean. Madrid, Spain’s capital and largest city, stands in the center of the country.

On Spain’s northeastern border, the mighty Pyrenees Mountains separate Spain from France. These mountains once formed a barrier to overland travel between the Iberian Peninsula and the rest of Europe. Africa lies only about 8 miles (13 kilometers) south of Spain, across the Strait of Gibraltar.

Most of Spain is a high, dry plateau called the Meseta. North of the Meseta, mountains extend across the peninsula, giving Spain the second highest elevation in Europe, after Switzerland.

Thousands of years ago, a people known as Iberians lived in what is now Spain. Later groups that came to the area include Phoenicians, Celts, Greeks, Romans, and Germanic peoples. In the A.D. 700’s, Arabs and other Muslim people from northern Africa conquered most of Spain. In the 1000’s, Spanish Christians began to drive out the Muslims, finally defeating them in 1492. That same year, Christopher Columbus, an Italian navigator in the service of Spain, reached America.

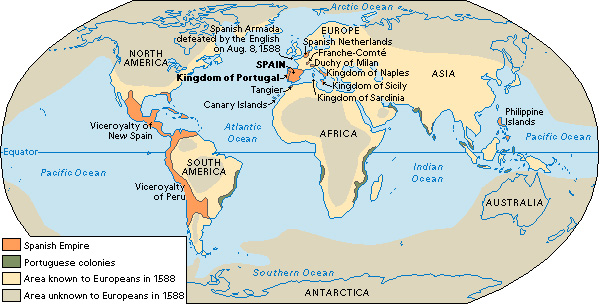

Columbus’s voyage touched off a great age of Spanish exploration and conquest. The Spaniards built an empire that included much of western South America and southern North America, as well as lands in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Spain held most of its empire until the early 1800’s. The huge shipments of gold and silver brought to Spain from its colonies, especially in the 1500’s and 1600’s, caused inflation (an increase in prices) and disrupted Spain’s economy. The government became financially dependent on American mines, which later declined in production. The Spanish government channeled enormous resources toward wars to maintain its empire and toward such luxuries as the arts and building churches and palaces. At the same time, it neglected to invest in agriculture, commerce, education, and industry. Because Spain was slow to industrialize and to educate its people, the country lagged behind most of its European neighbors until the mid-1900’s.

In the late 1930’s, a bloody civil war tore Spain apart. With the military help of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, General Francisco Franco established a dictatorship in Spain. Franco controlled the country until his death in 1975. Spain became a democracy after Franco died.

Government

Spain adopted a new constitution in 1978. The Constitution gave Spain a democratic form of government called a parliamentary monarchy. The main public officials are a king, a prime minister, and members of a cabinet and a parliament.

Spain's national anthem

The king

serves as the country’s head of state. He does not have a direct role in the operations of the government, but he has an advisory role in matters of policy. The king represents the country at important diplomatic and ceremonial affairs. Juan Carlos I, who reigned from 1975 to 2014, played an important role in the process that changed Spain from a dictatorship to a democracy.

The prime minister and cabinet.

The prime minister leads the national government. The prime minister appoints cabinet members to carry out the day-to-day operations of the government. The leader of the political party that holds the most seats in the parliament usually becomes prime minister.

The parliament

of Spain, called the Cortes, makes the country’s laws. The Cortes consists of a lower house called the Congress of Deputies, which has 350 members, and an upper house called the Senate, which has about 260 members. The Congress has greater power than the Senate. The people elect all of the deputies and most of the senators. Regional governments appoint about a fifth of the senators. The members of both houses serve four-year terms. Spaniards 18 years old or older may vote.

Local government.

Spain is divided into 50 provinces. The Constitution of 1978 grouped the provinces into 17 regions called autonomous (self-ruling) communities, thus creating a federal system. Each autonomous community has a popularly elected government and wide powers in such areas as education and culture. The national government controls defense and foreign policy, but the national and regional governments share many other areas of responsibility. Cities and towns have mayors and town councils, elected by the people.

Political parties.

The largest political parties in Spain are the center-right Partido Popular (Popular Party, or PP) and the leftist Partido Socialista Obrero Español (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), abbreviated PSOE. A left-wing party called Podemos (We Can) gained influence during the 2010’s. The Catalonia region in northeastern Spain and the Basque region in the north-central part of the country have their own local nationalist parties.

Courts.

Spain’s highest court is the Supreme Court. There are also territorial, provincial, local, and military courts, as well as the Constitutional Court of Spain.

Armed forces

of Spain consist of an army, a navy, and an air force. Military service is voluntary.

People

Spaniards live in an increasingly modern and urban society. Their standard of living is high. Most Spaniards eat and dress better, live in better homes, and receive more education and better health care than earlier generations did. Compared with people from other countries, Spaniards have a relatively long life expectancy.

Spain is a modern, industrial nation, but it maintains strong ties to traditional ways. Most Spaniards lived in rural areas before the country’s rapid economic development in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Many owned small farms. Others worked on large estates. A Roman Catholic church stood in the center of most villages, though many Catholics did not actively practice their religion. Regionalism and Catholicism remain important forces in Spanish life. But rapid economic and social change has reduced the influence of these forces on many people.

Ancestry and population.

People have lived in what is now Spain for more than 100,000 years. About 5,000 years ago, Iberians occupied much of Spain. During the next 4,000 years, other groups came to Spain as conquerors, settlers, or traders. Phoenicians, the first of these groups, were followed by Celts, Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Jews, Germanic peoples, and North African and Arabian Muslims. These groups mixed with one another and helped shape the ancestry of the present-day Spanish people.

About four-fifths of Spain’s people live in cities. The country has two cities with more than a million people. These cities are Madrid, the nation’s capital and largest city, and Barcelona, on the Mediterranean coast.

Language.

Castilian Spanish is Spain’s official language and the language spoken by most of the people. Pronunciation varies slightly from one region to another. See Spanish language.

In several regions of Spain, a second official language is used in addition to Castilian Spanish. Many people in Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Islands speak some form of Catalan, a language similar to southern France’s Provençal. Some Basques speak Euskara, also called Basque, which is not known to be related to any other language. In Galicia, in northwestern Spain, most people speak Galician, a language related to Portuguese.

City life.

Almost all city people live in apartments, and the majority of them own rather than rent their dwellings. Most families own television sets and computers. Although public transportation generally is efficient, most families own automobiles. City residents face problems with pollution and traffic jams.

A number of age-old customs survive alongside the newer trends. Until the late 1900’s, most Spanish stores and offices closed for lunch breaks of two to three hours and then stayed open until 7 p.m. or later. Some businesses still keep these hours. Some Spaniards still take a siesta (nap or rest) after lunch, though most people no longer follow this custom. Spaniards enjoy a paseo (walk) before their evening meal, which they often do not eat until 9 or 10 p.m. Spanish people also go to sidewalk cafes, bars, and clubs, where they visit with friends and family and drink coffee, soft drinks, or wine.

Country life

in Spain has changed much less than city life. Since the mid-1900’s, expanded electrical service, better farming methods, and modern equipment have helped make life easier for Spanish farmers. But agriculture has fallen far behind industry in economic importance, and rural standards of living generally are lower than those in the cities. In the mid-1900’s, many farmers moved to Spanish cities or to other countries to try to find employment. Nevertheless, some areas of Spain have successful farms focused on exporting high-quality products, mainly to other European nations.

Most farmers live in villages or small towns. Every day, they travel the roads between their homes and the fields, on foot or in vehicles. Unlike some city people, they take only a short lunch break. But the evening paseo is as popular in rural areas as in the cities.

Food and drink.

Spaniards eat large amounts of seafood, which they prepare in a variety of ways. Favorite types of seafood include crabs, sardines, snapper, and squid. Spaniards also enjoy stews. A popular dish is paella. It may consist of such ingredients as tomatoes, beans, snails, vegetables, chicken, rabbit, pork, and seafood, which are mixed with rice and cooked with a flavoring called saffron. A popular dish during warm weather is gazpacho, a cold soup made of strained cucumbers, garlic, olive oil, onions, tomatoes, and spices. Popular meats among Spaniards include beef, chicken, goat, lamb, pork, and rabbit. Bread is eaten plain or with cheese or butter.

Most regions of Spain produce wine, and most Spaniards drink wine with all meals except breakfast. They also enjoy a drink called sangria, which consists of wine, soda water, fruit juice, and fruit. Other popular beverages include beer, soft drinks, strong black coffee, and thick hot chocolate. The hot chocolate usually is served with deep-fried strips of dough called churros.

Recreation.

Spaniards spend much of their leisure time outdoors. They like to sit for hours at sidewalk cafes or in town or village squares. Summer vacations at Spain’s beautiful beaches have become increasingly popular. On weekends, city people often drive to the Spanish countryside for picnics or overnight trips.

Soccer is Spain’s most popular sport. Many cities have soccer stadiums that seat 100,000 or more fans. Other popular sports include basketball, cycling, handball, and tennis. Bullfighting remains one of Spain’s best-known spectacles, and most cities have at least one bull ring.

Religion.

A majority of people in Spain are Roman Catholic, but many do not actively practice their religion. Some Muslims, Protestants, and Jews also live in Spain.

During most of the period from 1851 to 1978, Catholicism was the state religion of Spain. During that time, and particularly under Francisco Franco, the government restricted the rights of non-Catholics in many ways. For example, only Catholic marriage ceremonies were legal. Under the 1978 Constitution, Spain has no state religion, and people of all faiths are allowed complete religious freedom.

Holidays.

The most important Spanish holiday period is Holy Week, celebrated by Christians the week before Easter with parades and other special events. Other celebrations honor local patron (guardian) saints. During the celebrations, which last several days, many villages fill with visitors. People decorate the streets, build bonfires, dance, sing, set off fireworks, and hold parades, bullfights, and beauty contests.

One of the best-known celebrations is the fiesta (festival) of San Fermín, celebrated each July in Pamplona. As part of the festivities, each morning for eight days, bulls are turned loose in streets leading to a bull ring. People run in front of the animals and into the ring, where bullfights take place later in the day.

Education.

Spain’s national and regional governments operate a system of primary and secondary schools that provide free public education. There are also Catholic schools and nonreligious private schools at the primary and secondary levels. Children from the ages of 6 to 16 must go to school. Up to age 12, they attend primary schools. Students from 12 through 16 years old attend secondary schools. Students ages 16 through 18 may continue their education in either a vocational training school or a college preparatory school.

Spain has dozens of public and private universities. Its leading universities include the Complutense University of Madrid and the University of Barcelona.

Museums and libraries.

The Prado in Madrid, Spain’s best-known museum, contains one of the world’s finest art collections. It features works by such great Spanish painters as Francisco Goya and Diego Velázquez, as well as by many foreign artists. Madrid’s other art museums include the Reina Sofía National Museum and Art Center, which exhibits Modern and contemporary art; and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, which has an outstanding collection of European paintings from the 1200’s to the 1900’s. Madrid also has the Museum of the Americas; the National Museum of Archaeology; and the Army, Navy, and Municipal museums. Visitors also may tour much of the Royal Palace.

Most major Spanish cities have museums that exhibit art from the surrounding region. Well-known museums include the Archaeological Museum of Seville and the Museum of Fine Arts in Seville; the National Art Museum of Catalonia in Barcelona; the Picasso Museum in Barcelona, devoted to the Spanish-born painter Pablo Picasso; and the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, a museum of Modern art. In Toledo, the house of the great painter El Greco has been made into a museum that exhibits many of his works.

Spain’s largest library is the National Library in Madrid. The Municipal Library of Madrid owns one of the world’s most complete collections of newspapers and magazines. Important historical documents are preserved in the General Archive of the Indies in Seville; the General Archive of Simancas, near Valladolid; and the National Historical Archive in Madrid.

The arts

Spain has a rich artistic tradition and has produced some of the world’s finest painters and writers. Spanish arts flourished during a Golden Age in the 1500’s and 1600’s, when the country ranked among the world’s leading powers. Spain’s arts then declined somewhat, but a rebirth occurred during the 1900’s. Loading the player...

Spanish traditional dance

Literature.

The oldest Spanish writings in existence are the Poem of the Cid and The Play of the Wise Men. Scholars believe both works date from the 1100’s, but they do not know who wrote them.

Spanish writers produced some of their best-known literature during the Golden Age. For example, Miguel de Cervantes wrote Don Quixote (1605, 1615), the world’s first classic novel and one of its greatest literary works. The playwright Pedro Calderón de la Barca vividly dramatized life’s dreams and realities in his famous play Life Is a Dream (written in 1635, first performed about 1638). For a more complete discussion of Spanish literature, including more modern writing, see Spanish literature.

Painting.

Leading Spanish painters of the Golden Age included El Greco, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, and Diego Velázquez. Francisco Goya, sometimes called the Father of Modern art, painted during the late 1700’s and early 1800’s.

Spain’s most famous artist of the 1900’s was Pablo Picasso. He created fine sculptures, drawings, graphics, and ceramics as well as paintings. Other leading Spanish painters of the early and middle 1900’s included Salvador Dalí, Juan Gris, and Joan Miró. In the late 1900’s, the country’s best-known artist was probably Antonio Tàpies, who created abstract multimedia paintings.

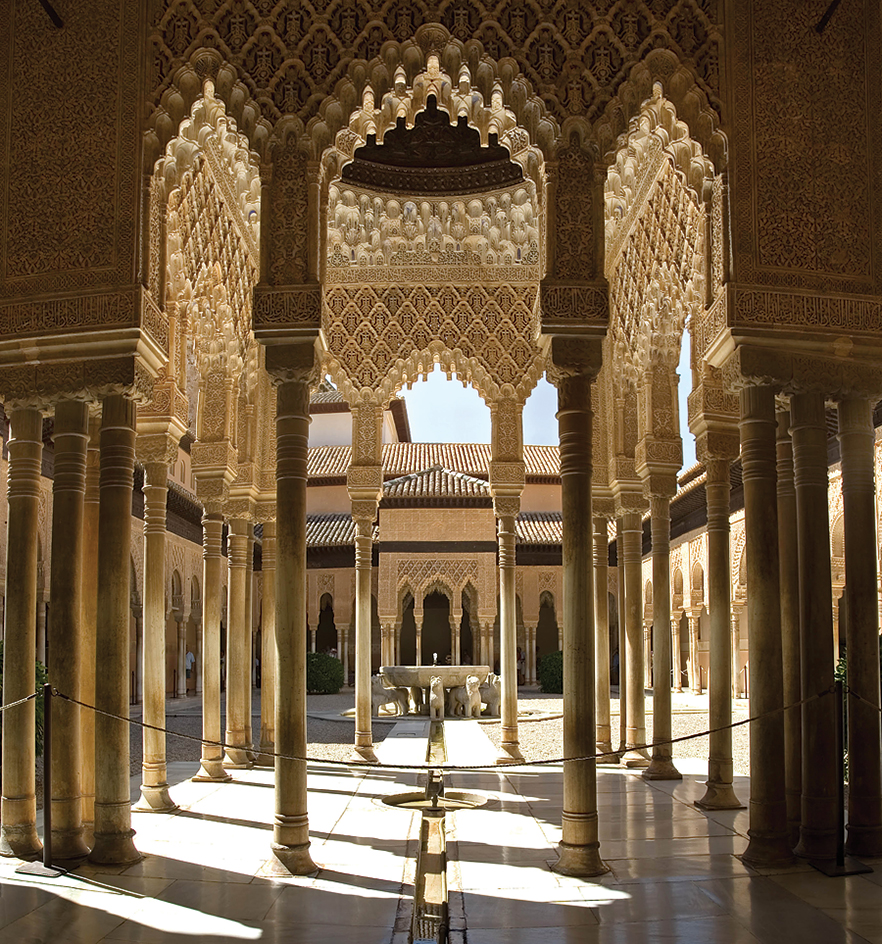

Architecture

in Spain reflects the influence of various peoples who controlled the country. Some aqueducts, bridges, and other structures built by the ancient Romans are still in use in Spain, and the ruins of other Roman structures stand throughout the country. Some southern cities have mosques (houses of worship) built by the Muslims, but most of these buildings are now Catholic churches. Córdoba’s huge cathedral was built as a mosque in the 700’s. More than 1,000 pillars of granite, jasper, marble, and onyx support its arches. The Muslims also built fortified palaces, the most famous of which is the magnificent Alhambra in Granada (see Alhambra).

Spain has hundreds of castles and palaces. The Escorial, a combination burial place, church, college, monastery, and palace, is about 30 miles (48 kilometers) northwest of Madrid. It was built in the late 1500’s and is one of the world’s largest buildings. The gray granite structure covers almost 400,000 square feet (37,000 square meters) and has 300 rooms, 88 fountains, and 86 staircases. The tombs of Spanish monarchs are in the Escorial. See Escorial.

About 10 miles (16 kilometers) from the Escorial is the Valley of the Fallen. A huge basilica built inside a mountain houses the remains of dictator Francisco Franco and about 70,000 soldiers who died in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). A 500-foot (150-meter) stone cross, the tallest in the world, stands on the mountain. An expansive esplanade and a Benedictine abbey spread out from the entrance of the basilica at the foot of the mountain.

The Gothic cathedral in Seville is the third largest church in Europe. Only St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and the basilica in Lourdes, France, are larger. The Seville cathedral measures 380 feet (116 meters) long and 250 feet (76 meters) wide, and the cathedral’s tower is 400 feet (120 meters) high.

Music.

Folk songs and dances have long been popular in Spain, and each region has its own special songs and dances. Musicians provide accompaniment on castanets, guitars, and tambourines. Spanish flamenco music and dance have become world famous.

Loading the player...

Spanish Fandango

In the 1700’s, Spanish composers created a form of light opera known as zarzuela. In the late 1900’s and early 2000’s, the Spanish soprano Montserrat Caballé and the tenors Alfredo Kraus and Plácido Domingo ranked among the world’s leading opera singers. Spain’s best-known musicians of the 1900’s included the cellist Pau (also known as Pablo) Casals, the composer Manuel de Falla, and the classical guitarist Andrés Segovia.

Motion pictures.

Spain’s first well-known director in the mid-1900’s was Luis Buñuel. He made two famous Surrealistic films with the painter Salvador Dalí—An Andalusian Dog (1929) and The Golden Age (1930). During most of the Franco dictatorship, Buñuel worked in exile in France and Mexico. He gained international attention in the 1950’s for his realistic and often cynical films about modern society.

Carlos Saura’s films won several international prizes from the 1960’s through the 1980’s and established him as the leading Spanish filmmaker of his time. Pedro Almodóvar directed internationally acclaimed films in the late 1900’s and early 2000’s. Such Spanish actors as Antonio Banderas, Javier Bardem, Penélope Cruz, and Carmen Maura became international stars.

The land

Spain has seven land regions: (1) the Meseta, (2) the Northern Mountains, (3) the Ebro Basin, (4) the Coastal Plains, (5) the Guadalquivir Basin, (6) the Balearic Islands, and (7) the Canary Islands.

The Meseta,

Spain’s largest region, is a huge, mostly dry plateau. It consists mainly of plains broken by hills and low mountains. Higher mountains rise on the north, east, and south. To the west, the Meseta extends into Portugal. Mainland Spain’s highest peak, 11,411-foot (3,478-meter) Mulhacén, stands in the Sierra Nevada range on the southern edge of the region. Forests grow on the mountains and hills, but only small, scattered shrubs and flowering plants grow on most of the plains. Goats and sheep graze in the highlands.

Most of Spain’s major rivers rise in the Meseta. The longest river, the Tagus, flows 626 miles (1,007 kilometers) from the eastern Meseta through Portugal to the Atlantic Ocean. The Guadalquivir flows 400 miles (640 kilometers) from the southern Meseta to the Atlantic.

The Northern Mountains

extend across far northern Spain from the Atlantic Ocean to the Coastal Plains. The region consists of mountain ranges in Galicia, in the west; the Cantabrian Mountains, in the central area; and the Pyrenees Mountains, on Spain’s border with France, in the east. The Galician and Cantabrian mountains rise sharply from the sea along most of the Atlantic coast.

Forests cover many of the slopes in the region, and short, swift-flowing rivers plunge through the mountains. Much of the region is pastureland, but farmers grow some crops on terraced fields.

The Ebro Basin

consists of broad plains that extend along the Ebro River in northeastern Spain. The Ebro, which is one of Spain’s longest rivers, flows 565 miles (909 kilometers) from the Northern Mountains to the Mediterranean Sea.

The Coastal Plains

stretch along Spain’s entire Mediterranean coast. The region consists of fertile plains broken by hills that extend to the sea. It is a rich agricultural area.

The Guadalquivir Basin

in southwestern Spain spreads out along the Guadalquivir River to the Atlantic. The basin is an extremely fertile region in the hottest part of the country.

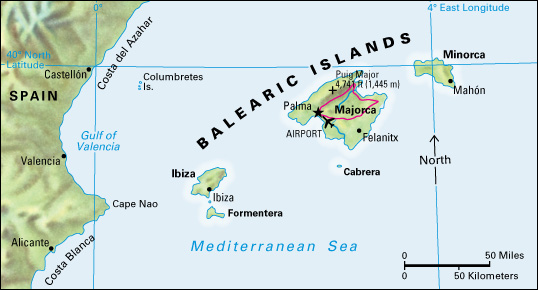

The Balearic Islands

lie about 50 to 150 miles (80 to 240 kilometers) east of mainland Spain in the Mediterranean Sea. Five major islands and many smaller ones make up the group. The three largest islands, in order of size, are Majorca, Minorca, and Ibiza. Majorca is a fertile island with a low mountain range along its northwest coast. Minorca is mostly flat, with wooded hills in the center. Ibiza is hilly.

The Canary Islands

lie in the Atlantic Ocean about 60 to 270 miles (96 to 432 kilometers) off the northwest coast of Africa. They include seven major islands, some of which are dry and some of which have tropical forests. The largest islands, in order of size, are Tenerife, Fuerteventura, and Gran Canaria. The volcano Pico de Teide, Spain’s highest mountain, rises 12,198 feet (3,718 meters) on Tenerife. Fuerteventura is flatter, drier, and less populated than Tenerife and Gran Canaria.

Climate

The Meseta and other inland regions of Spain have dry, sunny weather throughout the year. These regions, which make up most of Spain, have hot summers and cold winters. Summer and winter droughts, broken by occasional rainstorms, are common. Steady winds often whip up the dry soil. Snow covers upper mountain slopes in the Meseta region during most of the winter.

On the Coastal Plains and the Balearic Islands, mild, rainy winters alternate with dry, hot, sunny summers. Short, heavy rainstorms are common in winter, but summer droughts last up to three months in some areas. The sunny summers attract vacationers to the Balearic Islands and to Costa Brava, Costa del Sol, and other famous resort areas along Spain’s Mediterranean coast. The Canary Islands, also a popular vacation area, have mild to warm temperatures all year.

Winds from the Atlantic Ocean bring mild, wet weather to the Northern Mountains in all seasons. This region has Spain’s heaviest precipitation. Rain falls much of the time throughout the year, usually in a steady drizzle. There are many cloudy, humid days, and fog and mist often roll in from the sea. The Northern Mountains’ heaviest precipitation comes in winter, when the upper mountain ranges usually build up deep snow.

Economy

Spain plays an important role in Europe’s economy. Agriculture sustained the country for many years, and Spain is still among the world’s top producers of olives, wine, and many other agricultural products. Tourism thrives on Spain’s rich history and contributes much to the economy. However, a variety of modern enterprises have become the backbone of the country’s economy.

During the 1950’s and 1960’s, Spain transformed itself into a modern industrial nation. The country’s annual production of goods and services more than tripled. In 1950, about half of Spain’s workers had jobs in agriculture, forestry, or fishing. Today, about 75 percent of the workers are employed in services, about 20 percent in industry, and only about 5 percent in agriculture.

Natural resources.

Spain is not rich in natural resources. Most of Spain has poor soil and limited rainfall, which make it difficult to raise crops. The country lacks many important industrial raw materials.

One of Spain’s chief mined resources is the high-grade iron ore found in the Cantabrian Mountains. These mountains also contain coal, but it is mostly of low quality. Other products mined in Spain include copper, fluorite, gypsum, potash, and zinc.

Service industries

are economic activities that provide services rather than produce goods. Service industries account for about three-fourths of Spain’s employment and its gross domestic product (GDP)—the value of all goods and services produced in a country in a year.

Service industries are especially important to the economies of the large cities. For example, Madrid and Barcelona are the most important cities for banking and finance. Algeciras, Barcelona, Bilbao, Cartagena, Saragossa, Seville, and Valencia are major centers of wholesale trade.

Tourism

contributes greatly to Spain’s economy. Tourist activities benefit the country’s service industries, especially hotels, restaurants, and retail trade. Tens of millions of tourists visit Spain each year. Most visitors come from France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Visitors are drawn to Spain by its resorts on the warm, sunny Mediterranean coast and by its art, castles, colorful festivals, and food. In addition, many elderly Europeans retire to Spain.

The Spanish government encourages the growth of tourism, and it operates schools that train hotel managers, tour guides, chefs, and other people involved in tourism activities. The government also closely supervises the quality of services offered to tourists.

Manufacturing.

Spain ranks among the world’s leading automobile producers. Other important manufactured products include chemicals, electronics, iron and steel, machinery, paper products, plastics, processed foods, rubber goods, and ships and other transportation equipment. Barcelona, Bilbao, and Madrid are Spain’s chief industrial centers. Most of Spain’s steel mills are in the northern provinces. The Barcelona area manufactures chemicals, electronics, metal products, processed foods, and textiles and clothing. Madrid manufactures chemicals, electronics, processed foods, and other products. Cities with major motor vehicle plants include Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia, Valladolid, and Vigo.

Spanish companies are world leaders in the construction and engineering industries, developing such projects as dams, highways, and high-speed trains in many countries. Also important are companies that develop technologies to harness renewable energy sources, such as sunlight and wind.

Agriculture.

About half of the land in Spain is used for farming, either as cropland or as pastureland. Raising crops in most regions has always been a challenge because of the poor soil and dry climate. Many Spanish farmers own their farms. The rest work as hired hands or tenants on large farms.

Spain ranks among the world’s leading producers of lettuce, olives, oranges, peaches, pears, strawberries, sunflower seeds, tangerines, and wine. Other important crop products include apples, barley, corn, onions, potatoes, rice, sugar beets, tomatoes, and wheat. Grain crops are grown mainly in Spain’s northern regions and the Guadalquivir Basin. Farmers in the south and east produce most of the country’s grapes, olives, oranges and other citrus fruits, and vegetables. Bananas grow in the Canary Islands. The country’s important farm animals include beef and dairy cattle, chickens, goats, pigs, and sheep. Spain’s cured serrano (mountain) ham is famous.

During the late 1900’s, the government introduced modern methods and equipment to Spanish agriculture. The total area of irrigated farmland increased greatly. Irrigation improved yields in the Meseta’s driest areas, in the Ebro and Guadalquivir basins, and along the coast. Such advances increased farm production but also drastically reduced the number of people working in agriculture.

Fishing.

Spain ranks as one of Europe’s leading fishing countries. The chief fish and shellfish caught include blue whiting, cod, hake, mackerel, octopus, sardines, squid, swordfish, and tuna. Much of the catch comes from waters off Spain’s northern coast and from its high-seas fleet. Aquaculture, the commercial raising of plants and animals that live in water, is a growing industry in Spain. Mussels are the leading aquaculture product.

Mining.

Spain is one of the world’s leading producers of fluorspar, gypsum, and salt. Spain also mines clays, coal, copper, feldspar, iron ore, potash, sand and gravel, and zinc. The country produces a small amount of natural gas and oil.

Energy sources.

Hydroelectric, wind, and solar power plants generate about half of Spain’s electric power. Nuclear plants provide a small percentage of the country’s power, and plants that burn natural gas produce most of the rest. Spain imports nearly all its petroleum.

International trade.

Spain has always imported more goods than it has exported because of its limited natural resources. However, the income from Spain’s tourist business makes up for most of this imbalance.

Like most industrial countries, Spain imports some kinds of machinery and chemicals and exports others. Automobiles rank as Spain’s chief export. Other leading exports include fruits and vegetables, iron and steel, and refined petroleum products. The country imports automobiles, crude oil, and food products. Spain’s main trading partners include China, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Spain belongs to the European Union (EU), an association of European nations that work for economic and political cooperation. Spain and most other members of the EU adopted a common currency called the euro in 1999. The euro replaced the national currencies, including Spain’s peseta, in 2002.

Transportation and communication.

Spain has a good network of highways. A government-owned agency called Renfe operates an extensive railway system. Spain has a high-speed train network called AVE, which stands for Alta Velocidad Española (Spanish High Speed). The Spanish word ave means bird.

Spain’s chief international airport is Madrid-Barajas. Other leading international airports include Barcelona, Málaga, and Palma de Majorca. The islands of La Palma and Tenerife also have major international airports. Algeciras, Barcelona, Bilbao, Tarragona, and Valencia have large seaports.

Both the government and private companies operate Spain’s radio and television stations. Telefonica, a communications company based in Madrid, is among the world’s largest communications companies.

Spain has dozens of daily newspapers with a wide variety of political opinions. The largest newspapers include ABC, El Mundo, El País, all published in Madrid; and La Vanguardia, published in Barcelona. Internet and cell phone usage increased rapidly in the 1990’s and early 2000’s. Today, nearly all Spaniards have access to smartphones.

History

Early days.

Human beings lived in what is now Spain more than 100,000 years ago. At the beginning of recorded history—about 5,000 years ago—a people known as Iberians occupied much of Spain. They farmed and built villages and towns.

Phoenicians, who lived on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean, began to establish colonies along Spain’s east and south coasts in the 1000’s B.C. The Phoenicians carried on a flourishing trade with their colonies. Some of the cities they built, such as Cádiz and Málaga, have lasted to the present day.

Celtic peoples moved into Spain from the north about 900 B.C. and again about 600 B.C. They settled in northern Spain. Greeks landed in Spain about 600 B.C. and later established trading posts along the east coast.

During the 400’s B.C., the powerful northern African city of Carthage conquered much of Spain. Hannibal, the great Carthaginian general, attacked Roman Italy from Spain during the 200’s B.C. The Romans defeated Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.) and drove all Carthaginian forces from Spain.

Roman conquest

of Spain began during the Second Punic War. But the mighty Roman army took almost 200 years to conquer every region of Spain. Rome also conquered Portugal, and for the first time the entire Iberian Peninsula came under one government. The peninsula became a Roman province called Hispania. Spain’s name in Spanish, España, comes from Hispania.

Spain became a leading food-producing province of the Roman Empire, and many Romans went there to live. The Romans built cities in Spain and constructed excellent roads to all regions. They also erected huge aqueducts that carried water from rivers to dry areas. Several of Rome’s greatest emperors—including Hadrian and Trajan—were born in Spain. Such outstanding Roman authors as Martial and Seneca also came from Spain.

The Romans introduced Latin into the province, and the Spanish language gradually developed from the Latin spoken there. Christianity also was introduced into the province during Roman rule. Christianity became the official religion of the province—and of the Roman Empire—during the late A.D. 300’s. About the same time, the empire split into the East Roman and West Roman empires. Spain became part of the West Roman Empire.

Germanic rule.

During the 400’s, Germanic tribes began to establish kingdoms in the West Roman Empire. The empire finally collapsed in 476. One tribe, the Visigoths, gained control of the entire Iberian Peninsula by 573. They set up a monarchy in Spain that was the first separate and independent government to rule the whole peninsula. The Visigoths, who were Christians, tried to establish a civilization like that of the Romans. But continued fighting among the Visigoth nobles and repeated revolts of the nobles against the king weakened the nation.

Muslim control.

The Visigoths ruled Spain until the early 700’s, when Arabs, Berbers, and other Muslim peoples from northern Africa invaded the country. The invasion began in 711, and the Muslims conquered almost all the Visigoth kingdom by 718.

Following the Muslim conquest, many Spanish people converted to Islam, the religion practiced by the Muslims. The Muslims had a more advanced and tolerant culture than did most of medieval Europe. They had made great discoveries in mathematics, medicine, and other fields. They had also preserved many of the writings of ancient Greece, Rome, and the Middle East. In Spain, the Muslims made these works available to European scholars. They also constructed many buildings, including beautiful mosques and fortified palaces.

The unified Muslim government that controlled most of Spain collapsed during the early 1000’s because of internal conflicts. It then split into many small Muslim states and independent cities.

The Christian kingdoms.

Groups of Visigoths and other Christians in far northern Spain stayed independent after the Muslim conquest. They formed a series of kingdoms that extended from Spain’s northwest coast to the Mediterranean Sea. In the 1000’s, these kingdoms began to expand and push the Muslims southward.

Castile, in north-central Spain, became the strongest of the growing Christian kingdoms and led the fight against the Muslims. Many conflicts among the small kingdoms in Spain were more about politics and territory than religion. Sometimes, Christian and Muslim kingdoms became allies and fought against other kingdoms. A Castilian known as El Cid emerged as a hero for his daring military deeds. He fought mostly against Muslims, though he was often in the pay of Muslim rulers. See Cid, The.

In the 1100’s, several Spanish kings set up Cortes (parliaments) in their kingdoms to strengthen and broaden support for the government among their subjects. The Cortes brought representatives of the middle class, nobility, and Roman Catholic Church into the government.

Also during the 1100’s, the region that is now northern Portugal gained its independence from Castile. By the mid-1200’s, Portugal controlled all its present-day territory. Meanwhile, Spanish Christians continued to fight the Muslims. By the late 1200’s, the Muslim territory in Spain had been reduced to the Kingdom of Granada in the south. The Christian kingdoms of Aragon, Navarre, and Castile controlled the rest of what is now Spain. Aragon ruled most of eastern Spain and the Balearic Islands. Navarre ruled a small area northwest of Aragon. Castile controlled the rest of Spain. It remained Spain’s largest and most powerful kingdom throughout the 1300’s and most of the 1400’s.

Union of the Spanish kingdoms.

In 1469, Prince Ferdinand of Aragon married Princess Isabella of Castile. Isabella became queen of Castile in 1474, and Ferdinand became king of Aragon in 1479. Almost all of what is now Spain thus came under their rule.

Ferdinand and Isabella considered Jews and Muslims a threat to their goal of a strong monarchy. At the time, many peoples, including European Christians, were intolerant and suspicious of people outside their own group. In 1480, the Spanish monarchy set up the Spanish Inquisition, a court that imprisoned or killed Christians suspected of not following the church’s teachings. The Inquisition continued for over 300 years.

Ferdinand and Isabella’s troops defeated the Muslims in 1492. That same year, the last of the Spanish Jews who would not convert to Christianity were expelled from the country. Some Jews who had converted still practiced Judaism in secret, risking the Inquisition. Ferdinand seized the small Kingdom of Navarre in 1512 to complete the union of Spain. Muslims were expelled from other parts of Spain during the next 100 years.

The Spanish Empire.

In 1492, while working to unify Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella sent the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus on the voyage that took him to America. During the next 50 years, Spanish explorers, soldiers, and adventurers flocked to the New World. They often brutally conquered the peoples they encountered there. The Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed Central America in 1513 and became the first European to see the eastern shore of the Pacific Ocean. Hernán Cortés conquered the mighty Aztec Empire of Mexico in 1521. By 1533, the huge Inca Empire of western South America had fallen to Francisco Pizarro. These men and other Spaniards explored much of South America and southern North America.

By 1550, Spain controlled Mexico, Central America, most of the Caribbean, part of what is now the southwestern United States, and much of western South America. In the Treaty of Tordesillas, in 1494, Spain and Portugal had agreed to a line that divided the New World between them (see Line of Demarcation). But the two powers could not secure the land because England, France, and the Netherlands claimed much of it.

While its empire grew in America, Spain also seized territories in Europe and Africa. Spanish troops reconquered formerly Aragonese territory in what is now southern France. They also took much of Italy, the Canary Islands, and land in northern Africa.

In 1516, a grandson of Ferdinand and Isabella became King Charles I of Spain. Charles had ruled the Low Countries (now Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands), and he brought these lands into the Spanish Empire. His father belonged to the Habsburg royal family, rulers of the Holy Roman Empire in central Europe. Charles became Holy Roman emperor in 1519. He ruled the empire as Charles V and Spain as Charles I.

The Spanish Empire reached its height during the reign of Charles’s son Philip II, who became king in 1556. In 1580, Philip, the son of a Portuguese princess, was one of several nobles with a possible claim to the Portuguese throne after the king died. Philip enforced his claim to the throne by invading and conquering Portugal. Philip’s rule was characterized by a growing intolerance toward certain minorities, especially groups with beliefs or practices that the Catholic Church in Spain considered unacceptable.

Spain gained control of the Philippine Islands during the late 1500’s. Spain also fought to defend western Europe from the expanding Ottoman Empire.

The Spanish decline.

Although Philip II ruled a worldwide empire and Spain was the strongest nation in Europe, signs of strain began to appear. Wars, inflation, and poor management weakened Spain’s economy. Philip’s attempts to protect his inherited kingdoms and to slow the advance of Protestantism in Europe met serious opposition from the Netherlands and England. In the 1560’s, the Netherlands rebelled against Philip. In 1588, Philip launched a great Spanish Armada of about 130 ships in an unsuccessful attempt to conquer England. English ships repelled the armada, and storms destroyed many of the Spanish ships during the retreat.

In the 1600’s, wars, rebellions, economic crises, and ineffective rulers weakened Spain. Fighting in the Netherlands continued into the early 1600’s. Spain heavily financed the Roman Catholic cause in the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). It also fought wars with France and in 1640 faced rebellions in Portugal and Catalonia.

The last Spanish Habsburg, Charles II, had no children. In 1700, he named a French duke, Philip of Anjou, as heir to the Spanish throne. Philip was a grandson of France’s King Louis XIV, who reigned in France from 1643 to 1715. Philip was also descended from the Spanish Habsburgs through intermarriage between the Spanish and French royal families. After Charles II died later in 1700, Philip became King Philip V of Spain, the first Spanish ruler from the French Bourbon family.

The rise of Philip V touched off the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). France fought England, the Netherlands, and other European nations that opposed French control of the Spanish crown. At the war’s end, Philip remained king of Spain, but the French were made to promise that they never would unite with the Spanish. In addition, Spain lost most of its possessions in Europe, and the British received Gibraltar and the Balearic island of Minorca. See Succession wars.

Bourbon reforms.

During the 1700’s, the Bourbon rulers of Spain carried out many government reforms. They centralized power by doing away with many traditional local tax privileges and by collecting taxes more uniformly. The Bourbon rulers also built roads and other public works, and the economy began to grow. The army and navy were reorganized and as a result became better able to protect trade between Spain and its American colonies. Meanwhile, strong ties developed between Spain and France because the rulers of both countries were Bourbons.

Conflict with Great Britain.

In the 1700’s, Spain and Great Britain (now also called the United Kingdom) challenged each other for colonial power in the Americas. In addition, Spain wanted to regain Gibraltar and Minorca from the British. As a result, Spain joined several other European nations in wars with Britain.

Spain also declared war against Britain in the American Revolution (1775-1783). In 1779, Spanish troops invaded Florida, which Spain had lost to the British in 1763. The Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution, returned Florida to Spain and recognized Spain’s control of Minorca, which Spanish troops had taken in 1782. Continued warfare against Britain weakened Spain, which ceased to be a naval power after the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

French conquest.

Napoleon Bonaparte seized control of France in 1799. At first, he allied France with Spain. French and Spanish ships fought together against the British at the Battle of Trafalgar. But in 1808, French forces invaded Spain and quickly took over the government. Napoleon forced Ferdinand VII to give up the Spanish throne and named Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother, king of Spain.

Some upper-class liberals supported Joseph. However, the majority of Spaniards bitterly resisted the French occupation. They struck back with a hit-and-run method of fighting called a guerrilla (little war). The United Kingdom joined Spain and Portugal against France in the Peninsular War later in 1808.

During the Peninsular War, the Spanish Cortes—which had fled from Madrid to Cádiz—drew up a new constitution for the country. The new constitution reduced the power of the Roman Catholic Church and increased individual rights and freedoms. However, it continued the Spanish monarchy. Supporters of the constitution were known as liberales (liberals).

Loss of the empire.

The French were driven from the peninsula in 1814, and King Ferdinand VII returned to the Spanish throne. He repealed the new constitution and persecuted the liberals. He also tried to regain control of Spain’s overseas empire. During the Peninsular War, most of Spain’s American colonies had revolted and declared their independence. By 1825, Spain had lost all its overseas possessions except Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and several outposts in Africa. In addition, Spain remained torn politically between Ferdinand’s supporters and the liberals.

The reign of Isabella II.

In 1833, Ferdinand’s daughter succeeded him as Isabella II. A group called the Carlists opposed Isabella’s reign. They wanted Ferdinand’s oldest brother, Carlos, to be king and maintain Catholic tradition and absolute rule over Spain. The liberals supported Isabella. Conflict over the succession led to a civil war from 1833 to 1840. The liberals won the war, but corruption and quarreling between liberal factions and between liberals and other political groups created disorder throughout Isabella’s reign. In 1868, a group of army officers led a democratic revolt that forced the queen and her family to leave the country.

Six years of political unrest followed the overthrow of Isabella. A new republican government was established in 1873, but another civil war broke out between the Carlists and the liberals. The army overthrew the new government in 1874 and, in 1875, brought Isabella’s son back to Spain to become King Alfonso XII.

The reign of Alfonso XIII.

Alfonso XII died in 1885, six months before his son, Alfonso XIII, was born in 1886. The baby’s mother, Maria Cristina of Austria, ruled in his place until he became old enough to take the throne in 1902.

Cuba and the Philippines, Spain’s most important colonies, rebelled in the 1890’s. The United States supported Cuba and declared war on Spain in April 1898. In August, the Spanish-American War ended with Spain’s defeat. Spain gave Cuba its independence and surrendered Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico to the United States. All that remained of the once mighty Spanish Empire were a few outposts in northern Africa. See Spanish-American War.

During the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, the power of the Cortes and the prime minister increased. At the same time, Spanish political parties and labor unions gained strength. The liberals and the conservatives, who both favored authoritarian government, manipulated elections so that they alternately controlled the government. Democrats and socialists, who wanted reforms, and labor union leaders organized frequent protests against the government.

Spain remained neutral in World War I (1914-1918) and profited greatly by selling industrial goods to the warring nations. But the war caused inflation, and wages trailed behind prices. The end of the war brought widespread unemployment in Spain. These conditions added to a growing discontent with Alfonso’s rule.

In 1912, Spain gained control over parts of Morocco (see Morocco (French and Spanish control). But the Moroccans would not submit. In 1921, rebels overwhelmed a large group of Spanish soldiers at Annual, in northern Morocco, and continued to attack as the Spaniards retreated. They killed more than 8,000 Spanish troops. The revolt in Morocco caused bitter disputes, which intensified as the fighting continued. Opponents of the king and his generals accused them of being ineffective and corrupt. Coupled with Spain’s political unrest and poor economy, the Moroccan conflict led to strikes and violence throughout Spain.

In 1923, General Miguel Primo de Rivera led a military revolt to take over the government and restore order. King Alfonso supported Primo, who became prime minister with the power of a dictator. Primo restored order in Morocco and Spain. He promised to reestablish constitutional government in Spain, but he repeatedly delayed. The army and the public finally turned against Primo in 1930, and he was forced to resign.

After the Primo dictatorship fell, a movement for a republican form of government gained strength in Spain. Supporters of the movement included liberals, socialists, and some former monarchists. The strength of support for the movement forced King Alfonso to allow free municipal elections, which were held in April 1931. The people voted overwhelmingly for republican candidates. Alfonso then left the country, though he refused to give up his claim to the throne.

The Spanish republic.

Republican leaders took over the government after Alfonso left Spain. In parliamentary elections in June 1931, liberals, socialists, and other republican groups won a huge majority in the Cortes. The new Cortes immediately began work on a democratic constitution, which was approved in December 1931. The Cortes elected Niceto Alcalá Zamora, a leading liberal, as the first president of the republic.

The republicans had won control of the government, but political unrest continued. Some Spaniards still favored a monarchy. In addition, the various republican groups were only loosely united. Anarchists (individuals opposed to the existence of established government) agitated for the overthrow of the republic and created uprisings in various sections of the country. The worldwide economic depression of the 1930’s added to these difficulties. Spain’s exports fell, and poverty increased. The Spanish people became disillusioned when government reforms failed to produce immediate results.

The new government reduced the power of the Catholic Church and gave greater power to the labor unions. It took over estates held by aristocrats and increased the wages of farmworkers. In 1932, the Cortes yielded to demands from nationalists in Catalonia and granted the region limited self-government. Other regions then demanded similar control over their own affairs.

The republican government’s actions created opposition among more and more Spaniards, especially conservatives. The conservatives supported the Catholic Church, and many wanted Spain to become a monarchy again. In parliamentary elections in 1933, a newly formed conservative party emerged as a powerful political force. This party was the Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Rightist Parties), called the CEDA. Spaniards perceived the CEDA as being antirepublican. Although CEDA won the most seats in the parliament, it did not have enough support to form a government. Spain’s president asked the Radical Party, actually a moderate centrist party, to form a government. However, the Radicals needed CEDA’s support to pass legislation.

In 1934, some CEDA members joined the Radical Party government. In response, socialists and Catalan nationalists led an uprising against the government. The uprising succeeded in the Asturias region and, briefly, in Barcelona, but it failed elsewhere. Fighting and violent repression by the government killed more than 1,300 people and wounded many more.

The political division in Spain widened. Some army leaders, monarchists, fascists, and Catholic groups made up the Right. Communists, socialists, labor unions, and liberal groups formed the Left.

President Alcalá dissolved the Cortes and called an election, which took place in February 1936. Leftist forces joined in an alliance called the Popular Front and won the election by a slight margin. Their victory touched off increased violence. Rightists and Leftists fought in the streets. The Right claimed that public order was collapsing while the government did nothing. The government accused the Right of causing the violence.

Civil war.

In July 1936, Spanish Army units stationed in Morocco proclaimed a revolution against Spain’s government. About half of the Army units in Spain then rose in revolt, and they soon won control of about a third of the country. The rebels hoped to overthrow the government quickly and restore order in Spain. But Popular Front forces took up arms against the rebels.

In September 1936, the rebel leaders chose General Francisco Franco as their commander in chief. By this time, the revolt had developed into a full-scale civil war. Franco’s forces became known as Nationalists or Rebels. Spain’s fascist political party, the Falange Española (Spanish Phalanx), and the Carlists supported the Nationalists. The forces that fought to save the republic were called Republicans. Violent, bloody conflict raged across Spain for nearly three years.

The Spanish Civil War drew international attention. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy supported Franco’s forces, even though France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and other European nations had agreed not to intervene in the war. Only the Communist Soviet Union and Mexico aided the Republicans. Republican sympathizers from France, the United Kingdom, the United States, and many other countries joined the International Brigades that Communists formed to fight in Spain.

By the end of 1937, the Nationalists clearly held the upper hand in Spain. They had taken all of western and most of northern Spain, and they were gradually pushing the Republican forces to the east. The Soviet Union ended large-scale aid to the Republicans in 1938, and the Republicans’ defeat became likely.

Franco entered Madrid, one of the last Republican strongholds, on March 28, 1939. The remaining Republican forces throughout Spain surrendered by the end of the month, and Franco announced on April 1 that the war had ended. Several hundred thousand Spaniards died in the war, and more were killed under Franco’s dictatorship, which replaced the republic.

World War II (1939-1945)

broke out five months after the Spanish Civil War ended. Officially, Spain remained neutral in the war. But Franco drew closer to Germany after the fall of France in 1940, when it seemed that Germany would win the war. Franco intended to join Germany and developed plans to win back Gibraltar, obtain some of France’s North African colonies, and invade Portugal. Later, as the tide of war began to turn against Germany, Franco became friendlier toward the United Kingdom, the United States, and other Allied countries.

Involvement in the Cold War.

In 1945, the Soviet Union launched a campaign calling for international opposition to Franco and for the overthrow of his government. Western nations supported this campaign because of Franco’s dictatorial policies and because of his support of Germany and Italy in World War II. Nearly all major countries broke off or froze diplomatic relations with Spain in 1945 and 1946.

In 1947, Franco announced that a king probably would succeed him upon his death or retirement. Franco hoped this announcement would reduce international criticism of his rule. But it was the growing Cold War—the struggle between Communist and non-Communist nations—that finally led the Western powers to ease their stand against Spain during the late 1940’s.

Franco strongly opposed the Communist nations, and the United States sought his help to strengthen the defense of Western Europe. In 1953, Spain and the United States signed a 10-year military and economic agreement. Franco allowed the United States to build Air Force and Navy bases in Spain, and the United States gave Spain more than $1 billion in grants and loans. In 1992, U.S. air bases in Spain closed. A naval base and a few small military facilities still operate.

Growth and discontent.

The 1940’s and 1950’s were years of poverty and suffering for ordinary Spaniards. During the 1960’s, however, Spain achieved one of the highest rates of economic growth in the world. The nation’s automobile, construction, and steel industries boomed, and the Spanish tourist trade flourished. As a result, most Spaniards’ standard of living rose rapidly.

In the mid-1960’s, the government eased some restrictions on personal freedom. In 1966, for example, the government relaxed its strict censorship of the press. But many people thought the government had not done enough, and protests erupted. Demonstrations began in 1968 at the universities of Barcelona and Madrid.

Some people in the Basque provinces demanded independence for their region. Others did not favor independence but called for greater control over their own affairs. Protesters in the regions of Andalusia, Catalonia, Galicia, and Valencia also expressed grievances and were put down by the authorities.

In the late 1960’s, a Basque organization named Euskadi ta Askatasuna (Basque Homeland and Freedom), commonly abbreviated ETA, began a terrorist campaign against the Spanish government. Under Franco, many Basques and other Spaniards were arrested for revolutionary activities, and some were executed.

Political changes.

Franco died in 1975, and Spain entered a period of major political change. The country quickly began a process of establishing a democratic government to replace Franco’s dictatorship.

In 1969, Franco had declared that Prince Juan Carlos, a grandson of King Alfonso XIII, would become king of Spain after Franco’s death or retirement. Juan Carlos became king two days after Franco died. In 1976, he made Adolfo Suárez González prime minister.

In 1976, Spain’s new government ended Franco’s ban on political parties other than his own. In 1977, the government held free elections in which several parties competed for seats in the parliament. This marked the first time since 1936 that the people of Spain had a choice of candidates in parliamentary elections. In the elections, the Unión de Centro Democrático (Union of the Democratic Center, or UCD), headed by Prime Minister Suárez, won the most seats.

In 1978, the voters of Spain approved a new constitution based on democratic principles. In elections held after the adoption of the Constitution, the UCD again won the most seats in parliament. In 1981, Suárez resigned as prime minister. Juan Carlos appointed Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo, also of the UCD, to succeed Suárez.

Spain’s democratic government began a process of increasing local government power in the country’s regions. In 1980, people in the Basque provinces and Catalonia elected regional parliaments. Since then, the people of all other regions have also elected parliaments. In the Basque region, separatists, though a minority, continued their terrorist campaign for total independence.

In elections in 1982, the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, or PSOE) won the most seats in parliament. Felipe González, the party’s leader, became prime minister. The elections gave Spain its first leftist government since 1939. The PSOE won again in 1986, 1989, and 1993, and González remained prime minister.

In the 1996 and 2000 elections, the center-right Popular Party won the most seats in parliament. Its leader, José María Aznar, became prime minister. During this time, the economy grew spectacularly.

The early 2000’s.

Shortly before general elections in 2004, bombs exploded on commuter trains in Madrid, killing nearly 200 people. The government blamed ETA for the bombings, even after evidence showed that Islamic terrorists were actually responsible. Many Spaniards were angry that the government had given them misleading information about the attacks. As a result, voters increasingly supported the PSOE, which won control of parliament. The leader of the Socialists, José Luiz Rodríguez Zapatero, became prime minister.

Zapatero’s government introduced policies to expand Spain’s welfare system and to integrate millions of immigrants from Latin America, eastern Europe, and North Africa into Spanish society. The government also worked to modernize the economy by investing more in education and research. In 2005, Spain’s government legalized same-sex marriage.

In 2006, ETA declared a permanent cease-fire. However, the police blamed ETA for new incidents of violence, and Prime Minister Zapatero suspended peace talks with ETA. In 2010, and twice in 2011, ETA announced that it would stop its campaign of violence. The group disarmed in 2017 and dissolved itself in 2018.

In 2007, Spain’s parliament passed a bill that formally condemned Francisco Franco’s dictatorship. The bill required local governments to fund projects to dig up mass graves of people killed by Franco’s Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War. All monuments and symbols that honored Franco’s regime were ordered removed from public places. The bill also declared unlawful all trials that led to the execution or imprisonment of Franco’s opponents during his rule.

In 2008, Prime Minister Zapatero’s PSOE again won Spain’s general election, but without a majority of seats in the parliament. The party formed a minority government, and Zapatero remained prime minister. The conservative Popular Party defeated the PSOE in a general election in 2011. Party leader Mariano Rajoy became prime minister of Spain in December.

Spain suffered a severe economic recession following a global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009. In 2012, facing continued economic difficulties, Spain accepted a 100-billion-euro ($125-billion) emergency loan from the countries that use the euro.

Nearly 80 people were killed when a speeding train derailed and crashed near Santiago de Compostela, in northwestern Spain, in July 2013. Dozens more people were injured.

In 2014, King Juan Carlos abdicated (gave up) the throne to his son, Prince Felipe. The announcement followed a number of scandals involving the royal family.

In 2014 and again in 2017, Catalan voters backed independence for Catalonia in nonbinding referendums. Spain’s Constitutional Court dismissed both referendums as unconstitutional. It also dismissed independence resolutions passed by Catalonia’s regional parliament in 2015 and 2016. Prime Minister Rajoy tried to stop the 2017 referendum, which his government considered illegal. Spanish national police raided Catalan political offices, arrested separatist politicians, and forcefully closed polling stations. National police in riot gear clashed with pro-independence voters and activists, and several hundred Catalans were injured. Protests against the police crackdown took place in Barcelona and throughout Catalonia. The Spanish government temporarily revoked Catalonia’s autonomous authority.

In June 2018, scandals within the Popular Party forced Rajoy from office, and he was replaced by the PSOE’s Pedro Sánchez. In a 2019 trial, the Spanish Supreme Court found a number of Catalan separatist leaders guilty of sedition (rebellion) and misuse of public funds for their roles in organizing the 2017 independence vote. Sánchez’s government pardoned nine of the separatists in 2021.

Spain in 2020 became one of the countries hardest hit by the respiratory disease COVID-19. The disease first broke out in China in late 2019 and spread throughout the world. In March 2020, Spanish authorities declared a national state of emergency, issuing strict limits on business activity, travel, and public gatherings to combat the spread of the virus. The government later increased or relaxed business and social restrictions based upon changes in infection rates. Vaccines first became available to high-risk groups late in 2020. By early summer 2021, higher vaccination rates had contributed to steep declines in infection and death rates. Highly contagious variants of the disease continued to spread, however, leading to further outbreaks. By early 2023, nearly 14 million COVID-19 infections had been recorded in Spain, and about 120,000 Spaniards had died from the disease.

In July 2023 elections, the conservative Popular Party won the most seats in Spain’s parliament but could not assemble a coalition to form a majority. In November, the PSOE’s Sánchez secured his return as prime minister by offering Catalonia’s pro-independence parties amnesty (an official pardon) for hundreds of politicians and activists who participated in the 2014 and 2017 referendums. The amnesty proposal angered conservative voters, who held large protests in a number of cities.